Transylvania was characterised by a unique social structure, as well as tolerant religious and cultural policies after the 1526 Tragedy of Mohács, thus it is sometimes referred to as ‘the Switzerland of the East’. Thanks to the deliberately planned settlement and the spontaneous (as in, without central control) influx of migrants, the region became religiously and ethnically diverse from the 13th century onward. Despite that, the Kingdom of Hungary maintained its supremacy for centuries. What was its secret? Despite what the historians of Romania tell us, it had nothing to do with oppressing the different nationalities living within its boundaries. Rather, it was the result of the desire to learn: the ‘peregrinations’ of Hungarian students to Western universities, the eagerness to learn about the arts and sciences, and the recognition of the importance of books and libraries yielded such a steep difference in intellect, such a cultural advantage, that the Hungarian novelty in Transylvania was predestined to give the political leaders of ‘the Fairy Garden’.

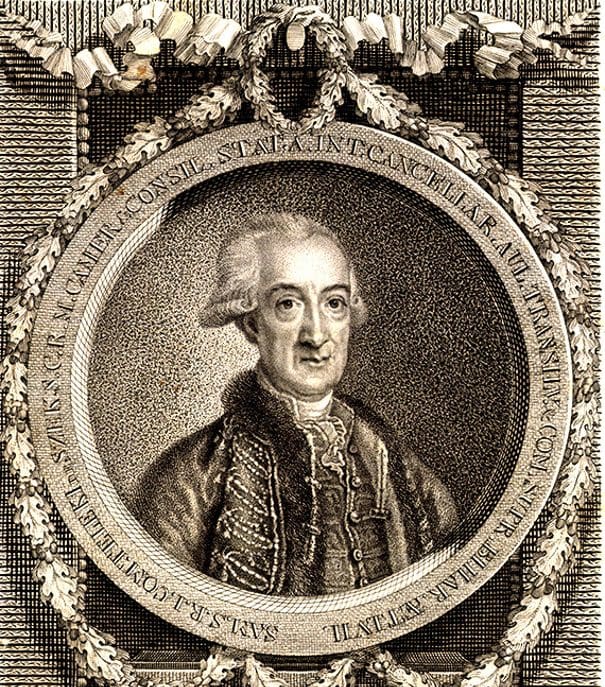

Count Sámuel Teleki, Chancellor of Transylvania, was also one of these Hungarian noblemen, who is unduly unknown in today’s society. To the general public, hardly anything is known about the deeds of the lawman so influential to Hungarian and Transylvanian culture.

Count Sámuel Teleki was born in 1739, in Gernyeszeg (Gornești) in Transylvania,

on the Eastern bank of the River Maros. He gave his soul back to his creator in 1822. He spent his childhood in Celna (Țelna), Fehér (Alba) County, where he started to help his father out with the running of their family estate very early on. He was studying Latin, religions, and natural sciences. However, his father’s (who was 61 when his son was born) death in 1754 forced him to suspend his studies for a period of time. Three years later, he sought permission from Queen Maria Theresa to continue his education abroad. Even though the Seven Years’ War was causing a lot of turbulence in Europe at the time, he was one of the first people to get the Queen’s approval. Count Teleki learnt to speak German and French shortly after. He was also studying world history, law, electrostatics, mathematics, and physics. He was visiting the lectures at the universities of Utrecht and Leiden.

In the spring of 1763, he began his journey back home, through Basel, to put his newly accumulated knowledge to use in his homeland. Teleki, an avid collector of books, sought out the libraries and librarians of big cities on his way home. After resettling home, he became a chamberlain at the Royal Court, then the Ispán of Küküllő County and an advisor to the Dicastery of Transylvania. From 1792, under the rule of Leopold II, he served as Vice-Chancellor of Hungary; and also as the Chief Ispán of Maros (Maramureș) County, then went on to be Chief Chancellor of Transylvania. Teleki was an honorary member of the Academies of Göttingen, Warsaw, and Jena as well.

According to court archives, Teleki was an active participant in the efforts to reform the country’s education system his whole life. His name comes up frequently in the discussions about public education in the 1770s and 1780s. As it is well-known, these were the times when an increasing need began to emerge for a centralised, modernised school system within the Habsburg Empire. This was when the so-called ‘school laws’ were written.

Queen Maria Theresa signed the decree reorganising the whole of Hungarian education, called Ratio Educationis, on 22 August 1777.

The order itself organised all educational institutions—regardless of their level or what domination it was connected to—into one unified system, as a result of which, all schools within the Kingdom of Hungary were under state governance all of a sudden.

For Catholics, this did not imply any inherent risks. For Protestants, however, who had essentially only given up ‘the right of supreme supervision rooted in law’ to the state prior, Royal oversight posed a great threat—if for nothing else, because of the censorship of textbook content.

Ratio Educationis could not be implemented in Transylvania, because of constitutional barriers (in accordance with the denominational and religious rights enshrined in the 1691 Diploma Leopoldium). Thus, a new set of regulations had to be drawn up there, in compliance with the local norms. This was Norma Regia. Sámuel Teleki, a devout Protestant, who was the Chief Custodian of the Protestant Collegium of Enyed, the caretaker of the foundations of three Transylvanian collegiums, and a consistent patron of the Reformed Church in Transylvania, recognised the underdeveloped state of the local education system. Therefore, he came to the conclusion that, despite the dangers of being under state control, reforms should be considered, and not be opposed over concerns for the local church administrations’ authority.

It’s no surprise that Teleki was selected to be a part of the Mixta Commissio, a council aiming to solve the problems related to the education of the youth of Transylvania. He held public offices under four different emperors (Maria Theresa, Joseph II, Leopold II, and Francis I)—four emperors who all had distinct, controversial styles of governing. He did so while never bowing down to the emperor, never becoming a ‘court servant’, never giving up on his moral values, never giving up his faith, never giving up on the interests of Transylvania, and never giving up on his primary goal, to raise up his people.

He did a lot to improve the state of public education in Transylvania, not just as Chief Chancellor, but also as a private citizen. This is evidenced by his attempted educational reforms in Sáromberke (Dumbrăvioara), where the Teleki family estate is located. Sámuel Teleki’s son Domokos (after consulting with his father, most likely), issued a decree in which 19 points of regulations compelled local parents to allow their children to go to school. These rules defined, among other things, the order of the lessons, the conditions for compulsory schooling for both boys and girls, proposed rewards for the best performing students, and divided the school schedule for summer and winter time lessons. It specifically mentioned the schooling of children from different denominations, which made way for the public education of Romanian (referred to as ‘Oláhs’ at the time) children in town.

‘Oláh children are to go to school as well. When catechism is taught, they can leave, and they need not go to school on Sundays either’, Domokos Teleki’s regulations stated. This is just another piece of evidence disputing the claims by Romanians today that the Romanian minority in Transylvania was discriminated against under ‘Hungarian rule’.

Apart from his active participation in public affairs, book collection was another lifelong passion for Count Teleki. After studying abroad for years, on his way home, he noted in his diary that he transported nine boxes of books from Basel to Ulm, weighing hundreds of pounds in total. He believed his collection only served its proper purpose if anyone could read it.

That’s how the Teleki Library of Marosvásárhely (Târgu Mureș) was born,

which already held 36,000 titles by 1816. The library, a fee tail of the Teleki family, was passed on to the heirs with the condition that, following strict library rules, anyone could read the books in its collection.

‘The library and the museum must be open at certain hours on certain days to those doing scientific work and those who wish to visit them; the books must be given out to those requested them one by one’, Teleki ordered in 1798. The library’s catalogue was made by Teleki himself, and he published it in four volumes. The citizens of Marosvásárhely took advantage of the opportunity. The reading log, kept since the summer of 1803, is a testament to that. Initially, one to three people visited the bibliotheca per day, but that number gradually increased up until the founder’s death. By 1812–1813, it was not rare to see six to eight visitors in one day. The Chancellor made room for his library, opened in 1802, by expanding the one-story tall, baroque residential building he inherited from his wife’s aunt, Kata Wesselényi. The expanded building served two functions from that point on: the old wing was still inhabited by family members, while the new wing housed the rooms of the new public library.

Partly thanks to Teleki’s library, Marosvásárhely became a cultural centre of Transylvania

where the first attempts to create a Hungarian scientific society were made in Transylvania, the Public Educators’ Society by György Aranka and company.

According to poet and politician József Bajza, the Teleki House was a true bastion of the Hungarian language, which was in danger of erosion at the time. For his political activities, his role in improving public education, and his efforts in advancing Hungarian culture, Sámuel Teleki should be regarded as one of the greatest Hungarian figures of 18th–19th century Transylvania.