‘Miracles’ is a book by C. S. Lewis, first published in 1947 and revised multiple times later on.

Although C. S. Lewis is perhaps most renowned for his widely popular Chronicles of Narnia series, which has left a mark on both the fantasy genre and the film industry, his philosophical and theological contributions are equally deserving of recognition. Among the latter corpus of texts, Hungarian Conservative has already reviewed his fundamental work Mere Christianity, a strong work of apologetics advocating for the Christian worldview in the modern era, explaining and defending what Lewis considered the very essence of Christianity.

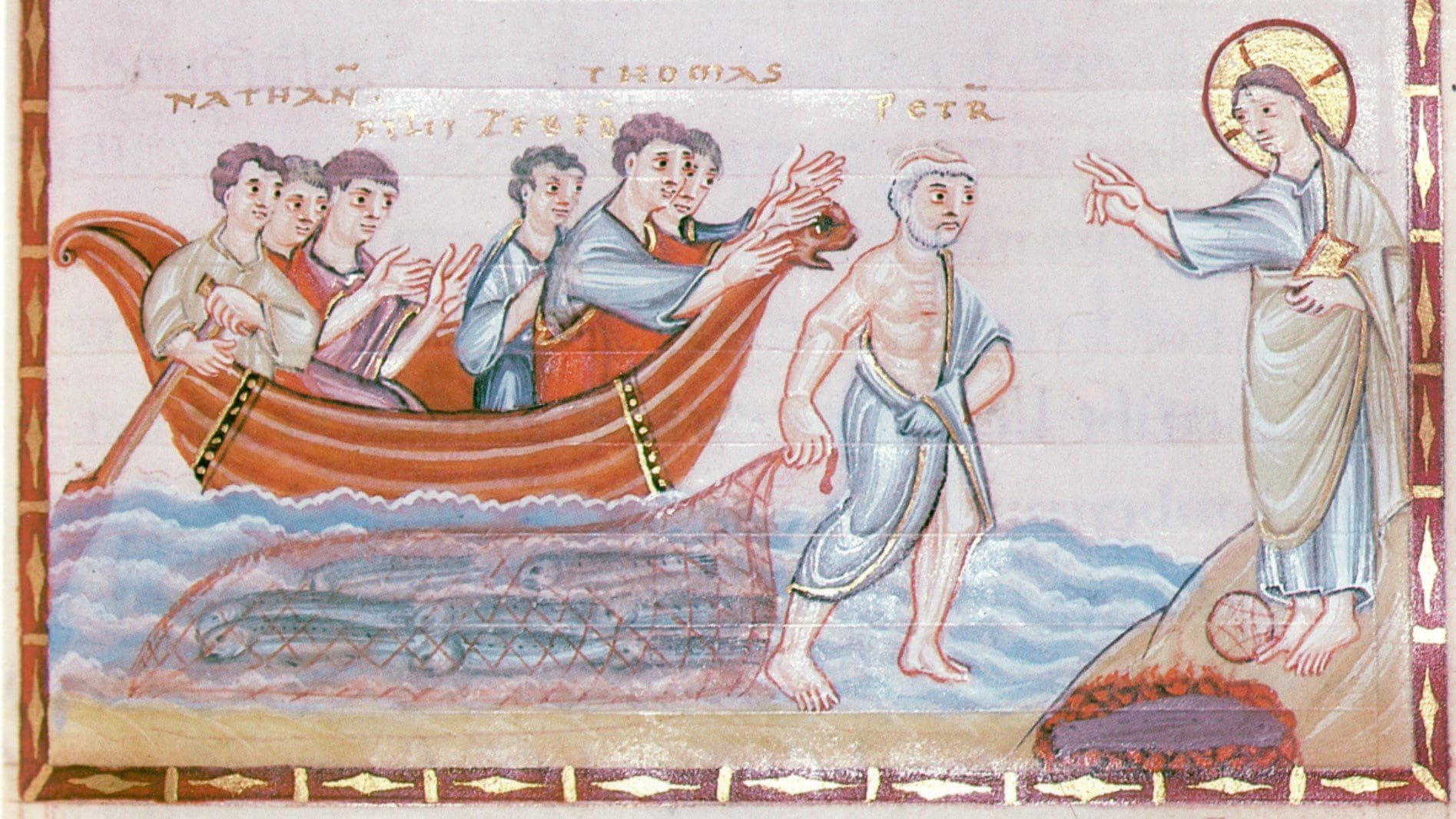

Miracles primarily focuses on the very specific topic of miracles within Christianity, that is, divine intervention into the natural order.

Lewis begins his deep metaphysical inquiry with a solid justification for his way of studying the topic—the way of philosophy. He claims that before delving into historical records or scientific experimentation to find out if a miracle can occur, one should settle the question of philosophy they adhere to:

‘…the question whether miracles occur can never be answered simply by experience. Every event which might claim to be a miracle is, in the last resort, something presented to our senses, something seen, heard, touched, smelled, or tasted. And our senses are not infallible. If anything extraordinary seems to have happened, we can always say that we have been the victims of an illusion. If we hold a philosophy which excludes the supernatural, this is what we always shall say. What we learn from experience depends on the kind of philosophy we bring to experience. It is therefore useless to appeal to experience before we have settled, as well as we can, the philosophical question.’

Continuing his exploration, Lewis embarks on a comparative journey between two highly widespread worldviews: the Naturalist and the Supernaturalist one, aiming to shed light on the essence of miracles by conducting this juxtaposition. The Naturalist worldview perceives the world in a deterministic and materialistic way. Such a lens presumes that everything in the world is connected and mutually influenced by each other. There, one phenomenon logically follows and precedes the other by strict laws of causation. It is a ‘closed system’ that is not influenced by anything outside of it (as there is nothing that lies ‘outside’ nature: by definition nature equals everything), to use the terminology adopted from natural sciences.

However, there exists an opposing viewpoint that aligns with the Supernaturalist worldview, which Lewis holds as true. Lewis arrives at this conclusion through an examination of the concept of human reason, the very tool that enables us to engage in discussions about the validity of Supernaturalism or Naturalism. He argues that if all our thoughts are the result arising from a purely deterministic chain of causes, from the physical level to the level of biology, as proponents of the comprehensive deterministic Naturalist framework assert, then there is no justification for presuming that these very considerations also follow from a rational foundation. Consequently, if Naturalism was indeed accurate, there would be no means of discerning its truth or anything else not directly stemming from a rational, biological and ultimately physical cause.

In this context, the true miracle is human free will and reason, bestowed upon us by God

—a divine intervention and a gift to humanity from the Creator.

Lewis effectively destroys the argumentation of the proponents of Naturalism, who assert that the foundation of the Supernaturalist perspective rests solely on belief, by applying to the Naturalist worldview itself—in certain realms of modern science, a notable incongruity emerges, which is not in line with strict Naturalism. For instance, the disparity between the theories of relativity and quantum mechanics showcases a clear disconnect, challenging the endorsement of a purely Naturalistic perspective according to which the world functions as a united machine. As Lewis explains:

‘Are we mistaking for an intrinsic probability what is really a human desire for tidiness and harmony? Bacon warned us long ago that ‘the human understanding is of its own nature prone to suppose the existence of more order and regularity in the world than it finds. And though there be many things which are singular and unmatched, yet it devises for them parallels and conjugates and relatives which do not exist. Hence the fiction that all celestial bodies move in perfect circles. I think Bacon was right. Science itself has already made reality appear less homogeneous than we expected it to be: Newtonian atomism was much more the sort of thing we expected (and desired) than Quantum physics.’

However, the possibility of divine intervention does not imply there are no physical laws in the Universe—Christianity does not contradict science, which postulates that there is, if not fully deterministic and ‘closed’, still a certain order and systematism in the events and things we observe. Instead, God's interventions are events that lack causes in preceding events, in contrast to the causal chain found in ordinary occurrences.

Whenever God intervenes, his intervention, although seemingly appearing ‘out of nowhere’, still follows the laws of the world that he has created.

For the reader to better understand that idea, take the example of the Immaculate Conception of the Virgin Mary—although her pregnancy appeared from a supernatural source, as there are normally no pregnant women who have not previously lain with men, the process of pregnancy itself is consistent with the regular laws of the Universe and the normal order of things. The life of Jesus itself—except for, of course, when he performed the biblical miracles, as he is not only man but also God—also follows the pre-created and regularly order of events. In this model, God creates a miraculous impetus which the Universes puts into order.

Hence, miracles are not incompatible with the presence of natural—scientific, if you will—laws. On the contrary: according to Lewis, there would not be any miracles if there were no laws:

‘If they were not known to be contrary to the laws of nature how could they suggest the presence of the supernatural? How could they be surprising unless they were seen to be exceptions to the rules? And how can anything be seen to be an exception till the rules are known? If there ever were men who did not know the laws of nature at all, they would have no idea of a miracle and feel no particular interest in one if it were performed before them.’

This fantastic study of divine miracles has undergone revisions and received additional chapters since its initial publication, which have only enriched the book and enhanced its quality. Today, it continues to stand as one of the most well-thought-out, modern and Scripture-based analyses of the nature of miracles, having significance that extends beyond the realm of Christianity.

Read more: