This article was published in Vol. 3 No. 2 of the print edition.

Branching connectivity may advance our economic position but is not a panacea, Zsolt Németh argues. In his keynote article, the Chairman of the Parliamentary Committee on Foreign Affairs reviews the cardinal points of Hungary’s impending strategy.

After the victorious election, the prime minister made it clear that the Russian aggression against Ukraine was forcing us to partially revise our strategy in foreign affairs, adjusting it to the changed circumstances. It is hardly surprising, then, that proposals and ideas of a strategic nature have increasingly claimed centre stage at in-camera government sessions and in public forums alike. The unfolding debate has so far been forward-thinking and auspicious, but to stay that course we must define our premises accurately, true to the facts, while avoiding even the appearance that our emerging strategy is built on a misunderstanding of the situation.

More Bloc Consolidation on the Way?

The assumption that the West is in decline while its global detractors are gathering strength must be taken with a grain of salt. The Russian attack on Ukraine, accompanied by other concurrent events, tells us just the opposite. Russia resorted to total aggression because by the 2010s it had lost its ability to keep Ukraine at bay using softer methods. Russia believed that it could still rectify the damage by military means, but the war has shown its inability to do so. The United States has no qualms about extending military support to Ukraine, and the latest military technologies being deployed by Russia have routinely proven inferior to American capabilities, of which only morsels have been committed for show.

Weapons from Iran can at best slow down Russia’s faltering without reversing the course of the war. China has maintained a distance from the Ukraine conflict, so the sophistication of its arsenal—unlike those of Russia, Iran, and the West—has not been put to the test. However, the visit to Taiwan by the American Speaker of the House obviously showed Washington’s intention to probe the degree of confidence China has in its own weaponry. Indeed, would there be a more opportune time for Beijing to ‘take care’ of the Taiwan issue by aggression than now, when the United States is tied up in Ukraine? The results of the probe have been clear: the United States is ready to undertake combat on two fronts if need be, and China prefers, to everyone’s relief, to refrain from putting its military prowess to the test.

For a long time now, wars have not merely been a matter of military strategy. Instead, they have constituted a showdown between industrial capabilities and technologies, fought in the eyes of the public. The perception of the duel between the West and its challengers as being fought on a level playing field has been largely relegated to the domain of false perceptions. In reality, the battle is far from being even, as the West is ahead on the scoring cards by a significant margin. Consequently, in devising Hungary’s strategy, we must inevitably start from the premise that the West stands to win. It may sometimes bungle tactical decisions—their own goal named energy sanctions is but one of several examples—but these blunders do not change the fact that the Ukraine War has unambiguously demonstrated the superiority of the West in terms of global technology and organization.

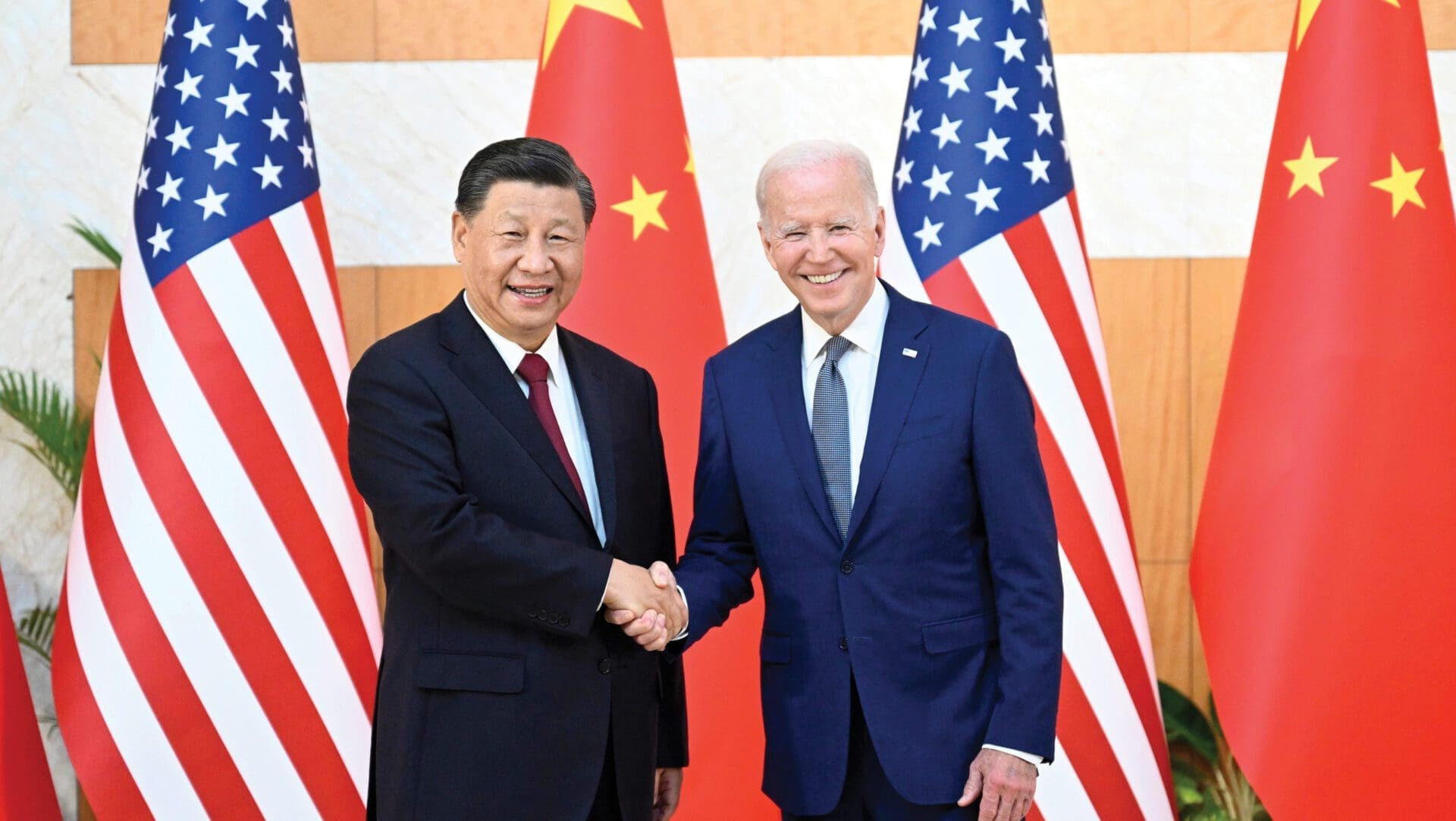

‘Bloc consolidation’, a notion currently popular in Hungary, is another term that must be used with caution. It may come to pass, or it may not. What seems certain is that we are not going to see a Russia-centred bloc emerge in the foreseeable future. Russia is not going to become the fulcrum of an entire bloc either because it will end the war on less than advantageous terms, or because it will sooner or later suffer military defeat. Potential participants in such a formation have begun to detach themselves from it, with the exception of Belarus, for the time being. It is true that, in recent years, we have been aware of two blocs being formed around the poles of the United States and China, but it is important to realize that a compromise between these two superpowers has beneficiaries with vested interests and considerable clout on both sides. Today, bloc consolidation seems just as feasible an outcome as an ‘unexpected’ compromise between the two superpowers. A case in point is the statements concerning the United States by China’s new Minister of Foreign Affairs Qin Gang, former ambassador to Washington.

Furthermore, we Hungarians must make a point of assessing the extent to which we are able to influence processes in world politics, first and foremost in the sense of our ability to mount meaningful resistance in the face of any effort at bloc consolidation. We would certainly be well advised to learn the lesson of our latest attempt, when we offered to act in the role of peace mediator in the Ukraine War, but neither party proved open to cooperation. Preventing the consolidation of a political bloc would be a much taller order.

Having said that, it is essential that we strive to prevent our being stuck on the periphery of any potential bloc being formed. This requires a precise strategy aimed at catapulting Hungary out of the group of moderately developed countries into the top echelon of advanced economies, which at heart is not a geographical issue. The choice between remaining on the periphery and aspiring to the centre—in other words, the transition from the middle to the high level of advancement—will come down to the position of Hungarian companies in international value chains as a function of producing small or great added value, the standards of the technologies applied throughout the national economy, and the disposal of resources vital for those technologies. In this latter connection, one of the most challenging strategic tasks facing us is the exploitation of opportunities in space diplomacy. New sectoral regulation adopted recently in Luxembourg clearly demonstrates that the size of a country does not necessarily relegate it to a marginal position.

Our rank in value chains and technology essentially depends on two factors: our own innovation capabilities and the foreign-sourced technologies defining our national economy and defence policy. This is why we must draw precise and well-founded conclusions from tragedies like the Ukraine War, which has served as the arena for a spectacular global contest between technologies and powers of innovation. In addition to steering clear of any bloc formation, this is another field where we must succeed if we are to close the gap between Hungary and the West.

The Limits of Connectivity

The notion that our position in terms of innovation and overall economic prowess benefits from a connectivity branching out in as many directions as possible does have merit, except that connectivity alone will never be a cure-all solution. Not only does it fail to address all of our problems, but it presents hazards of its own. It cannot be a universal remedy because in the global competition every entity is jealously guarding its own technologies and know-how.

Just because we build branching connections to all corners of the world, we will not necessarily have inched closer to the top rank. At the end of the day, we do need to rank potential strategic partners in one way or another, particularly in terms of the advantages afforded by cooperation with them.

‘The prime minister made it clear that the Russian aggression against Ukraine was forcing us to partially revise our strategy in foreign affairs’

The dangers of maximizing connectivity in all directions lie in the curiosity of every potential partner about our own strategic priorities. For those in possession of cutting-edge technology it matters a great deal who has what kind of access to our secrets, and who has insight into the technologies we are planning to implement. For instance, it would not be realistic for us to enter into no-holds-barred relationship building with Iran and Israel simultaneously, to give just one example. We would risk losing key opportunities in terms of technology and innovation, in terms of both civilian and military capacities, if the proprietors of the technologies to be entrusted to us regarded our international connections as a potential threat to the ‘bullet-proof’ security of those technologies. If we are serious about breaking out of the confines of mid-level development, it is therefore imperative to strike a well-considered balance in the connections we foster.

How much of our strategy we communicate is also crucial for securing truly high quality investment. Thematizing our diverse connections without being clear about their limitations may even become a liability instead of serving as the driving force for progress, as originally intended. This must be borne in mind in shaping the government’s narrative on Hungary’s strategy.

Forging Stronger Relations with Our Neighbours

The avowedly central role accorded to regional and neighbourhood policy bodes well for the future. Beyond considerations of culture, ethnic policy, and national security, taking advantage of regional synergies may be a sign of our ability to leave behind the status of moderate development. We must link into each other’s achievements, form joint ventures, and cooperate on shared inventions. But here too we would be well advised to compose our communication meticulously, in order not to leave our neighbours and regional partners in the dark about our intentions. We must define and articulate our goals without leaving a modicum of doubt in the eyes of our neighbours’ decision-makers about the fact that Hungary’s regional strategy serves the interests of an alliance focused on mutual goals. One obvious objective must be the improvement of our joint communication with Ukraine, if only because the majority of Ukrainian public opinion about Hungary has been in stark contrast to everything we have been doing for that country, even just in the past year.

Last but not least, taking action is one of the best tools of communication. If we are to further improve our regional policy in the eyes of the countries surrounding us, we must enhance Hungary’s readiness to propose initiatives and new avenues of cooperation in all regional forums, including not just the Visegrád Group (V4) but the Three Seas Initiative as well. A successful regional communication hinges on how well we know our immediate neighbours and the other countries in the wider region. It was with this in mind that we set up the Teleki László Institute, now sadly defunct. It would be worth our while to further our strategic goals by resuscitating this formerly authoritative institution in an updated form.

The strategic task ahead of us is a given, regardless of the means we choose to achieve it. If we are to emerge victorious from the next decade, we need to have in place a sound plan that is implemented well. The public dialogue now taking shape will certainly prove instrumental in creating a viable foreign policy strategy for Hungary.

Translated by Péter Balikó Lengyel.

Related articles: