The year 2022 saw the global population exceed 8 billion.[1] The decade of the 2020s, however, is also a period of dramatic structural changes in trends of global demographics. Three landmark demographic events are scheduled to occur in 2023: China’s population will be declining for the first time, India will surpass China as the most populous nation on the planet, and the total fertility rate for India will drop to a mere 2.0. These are landmark events of the tide turning in the demographics of most of the planet outside Africa. According to the most recent forecast of the United Nations Population Division, by the second half of the century, population growth will stop virtually everywhere except for Sub-Saharan Africa. This will result in tremendous change in roles and attitudes regarding the issues of migration and overpopulation. Instead of the setting that we can paraphrase as ‘the West (and Japan) versus Everyone Else’ that we got used to throughout past decades basically ever since the end of the Second World War, we will end up in a setting of ‘Africa versus Everyone Else’, where Sub-Saharan Africa remains the only source of significant migration, due to the threat of overpopulation. The rest of the world, in turn, will end up on the receiving end of migration and with the challenges of aging populations, it may have a good chance of not having to worry about overpopulation, provided that all regions outside Sub-Saharan Africa manage to avoid new overpopulation crises.

The demographic explosion, however, is scheduled to continue to run high in Africa. This means that Africa’s share is sharply rising in the world’s population. In 1990, the year we can consider as the start of our present age at the end of the Cold War, it was a mere 12 per cent of the global population. By 2023, it grew to 18 per cent; by 2050, it will be 26 per cent; and by 2100, it is scheduled to be as high as 38 per cent. In fact, the population of the world outside Africa will peak in 2054, and start shrinking from that point, falling even below 2023 levels by the end of the century. In fact, it already reached 90 per cent of that peak as early as 2021. Thus growth in the rest of the world outside Africa between 2020 and 2054 is to be a mere 10 per cent of the 2020 level, which is already close to stagnation. This suggests that regarding the threat of overpopulation causing humanitarian disasters, Africa will remain the region of most concern, and transcontinental migration from Africa will most likely intensify throughout the rest of the century, sooner or later reaching not only Europe, but the rest of the world as well.

Of course,

it is entirely possible that should economic policies successfully achieve a significant and steady increase in the standard of living in Africa,

as they did in the newly industrialized countries of Asia, population growth may slow down in Africa earlier than forecasts predict now. After all, it was not only China’s population that peaked earlier than previously predicted, but population growth in countries such as Bangladesh, India, and Indonesia also slowed down earlier, proving the truth of the proverb ‘capitalism is the best contraceptive’. If labour costs in the newly industrialized countries of Asia continue to rise, then investors searching for cheap labour may very well find their way to countries like Nigeria or Ethiopia, causing a more robust economic growth and an earlier slowdown of demographic increase than previously expected. The UN forecast also provides high, low, and median fertility scenarios for all regions. In this analysis, we use the median scenario. However, if we assume that in the upcoming decades,

Africa will see a robust economic growth similar to what Asia witnessed in the last few decades,

and that the median scenario does not consider that yet, and as a result, we calculate with the low fertility scenario for Africa and with the median scenario for the rest of the world, results will be more moderate. In this case, Africa’s population will peak at 2,825 billion in the year 2088, and then decrease to 2,767 billion by 2100, in which case it will make up only 30 per cent of the world population by that year instead of the 38 per cent forecast by the median scenario, while the population of the entire world will peak around the year 2070 at 9,76 billion, and start decreasing from that point. However, even in this case, the year by which Africa’s population reaches 90 per cent of its 2088 peak, and growth becomes hardly more than nominal after that, will be as late as 2061. So even if this latter scenario materializes, until the middle of the century we can still anticipate a rising risk of overpopulation-related humanitarian disasters in Africa, as well as an increasing transcontinental migration from Africa to the rest of the world, and change in these tendencies can only be expected only in the second half of the century.

The second half of the century is in the somewhat distant future, therefore it may be a world too far to discuss as part of our present. But the bulk of the demographic change will occur in most of Asia and Latin America as early as this decade, which by contrast is indeed already our present. And in this case, population growth coming to a halt in most of Asia and Latin America, combined with the dramatic growth of both the economy and the standard of living in most of the countries of these two continents, is already becoming somewhat of a game changer in our present.

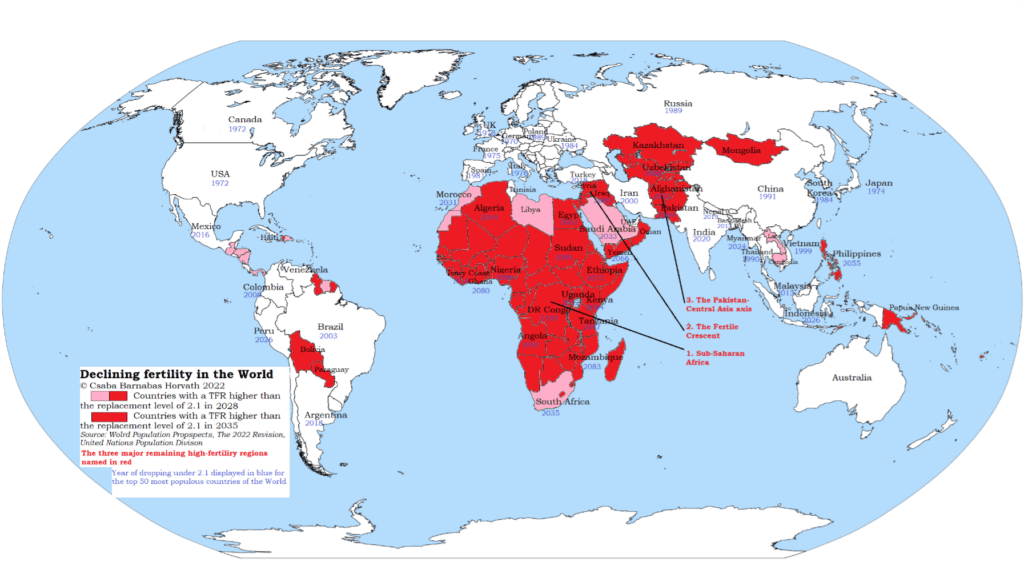

To measure demographic tendencies, a key number is the total fertility rate (TFR), a key threshold of which is called replacement rate. Total fertility rate is the average number of children that would be born to a woman over her lifetime. The replacement level, i.e. the rate necessary to maintain a certain population level, is considered to be 2.1. Below this rate, populations are destined to shrink. According to the most recent forecast of the United Nations Population Division, regarding major countries of Asia and Latin America,

the total fertility rate fell below the replacement level in Mexico in 2016, in Bangladesh in 2017, in Argentina and Turkey in 2018, and in India in 2020.

Myanmar will join the club in 2024, and Indonesia in 2026, while Brazil, Iran, Thailand, and Vietnam have already been under this level before the 2010s. Overall, as it can be seen on the map above, by the year 2028, TFR will decrease beyond replacement level basically everywhere outside Africa, the Arab world, and a conglomerate of countries in the middle of Eurasia consisting of Afghanistan, Pakistan, and post-Soviet Central Asia, which for the sake of simplicity, we can refer to as the Pakistan-Afghanistan-Central-Asia conglomerate. Outside Africa, the Arab World, and the Pakistan-Afghanistan-Central Asia conglomerate, the only country with a total fertility rate higher than 2.1, and a population higher than 30 million will be the Philippines. This also makes the Philippines the one and only non-Muslim majority country outside Africa with a population above 30 million and a fertility rate above replacement level after 2028. On the other hand, while most major countries with a fertility rate above replacement rate outside Africa are Muslim-majority, at the same time, out of the five most populous Muslim-majority countries outside Africa, namely Bangladesh, Indonesia, Iran, Pakistan, and Turkey, four (except for Pakistan) already are or will within the next five years reach sub-replacement levels in their fertility rates.

The UN forecast of course also predicts the Arab World and the Pakistan-Central-Asia axis to eventually decrease below the replacement level,

but puts this to happen further into the future than something that we could discuss as part of our present. Fertility rate is scheduled to fall below replacement level in Libya and Morocco in 2031, in Saudi Arabia in 2033, in Algeria in 2044, in Syria in 2046, in Jordan in 2047, Egypt in 2062, in the Palestinian Territories as well as in Yemen in 2066, and in Iraq only in 2080. In short, in most of the Arab World it will happen already by mid-century. It is interesting to note that despite being located further away from Africa, and surrounded by Russia, China, India, and Iran, all being under the replacement level already as of now, the Pakistan-Central-Asia axis will slow down to sub-replacement levels considerably later than the Arab World, with the fertility rate scheduled to decrease below 2.1 in Uzbekistan in 2050, in Pakistan in 2069, in Afghanistan in 2073, and in Kazakhstan only in 2075. This means that while change will occur in most of the Arab World by mid-century, it will only occur in the Pakistan-Central-Asia axis in the second half of the century.

The change that is occurring in countries where the total fertility rate has already fallen below replacement level or will do in the upcoming five years is tremendous. As a result of the combination of a demographic slowdown and a robust economic growth, not only Russia, China, Japan, and Korea, but also India, Bangladesh, and Southeast Asia, as well as Turkey, Iran, and Latin America are on the path to becoming low-fertility, middle-income countries, which will likely relieve them from the threat of overpopulation, and may even put them not on the source, but on the receiving end of transnational migrations.

Despite reaching sub-replacement fertility rates somewhat later, two regions of the Arab World can be also discussed as part of this trend. One of these is the Gulf States, where Bahrein, Kuwait, Qatar, and the UAE are already sub-replacement, and their major counterpart, Saudi-Arabia will fall into this category by 2033 as well. The other, more peculiar region is the Maghreb: during most of the last century,

the Maghreb region was known as the major source of transnational migration to France and the rest of Europe.

However, by now, not only the fertility rate is decreasing in this region, and by 2031, it will be on sub-replacement levels in three of the four countries of the region (Libya, Morocco, and Tunisia, with the sole exception of Algeria), but also the gap in terms of fertility, population, and wealth, is on the increase between the Maghreb and West Africa right south of it. West Africa is not only the most rapidly growing major region in the world in terms of population, but also includes most of the Sahel, a region seriously threatened by climate change.

While West Africa’s population was three times the size of the Maghreb in 2000, it will be five times the size of it in 2033, ten years from now.

All these factors set a trend for the Maghreb, where West African immigration to the region is becoming higher than Maghrebi emigration to Europe. Taking out these regions, out of the Arab World outside Africa, only the conglomerate consisting of Iraq, Jordan, the Palestinian Territories, and Syria (for the sake of simplicity we can refer to by its ancient name as the ‘Fertile Crescent’) remains in the low-income-high-fertility category. Here we can exclude Israel, because as a first-world economy, it is still rather on the receiving end of transnational migration, and the risk of humanitarian disasters due to overpopulation is also negligible.

In the southern tip of Sub-Saharan Africa, the triad of Botswana, Namibia, and South Africa also forms a region significantly different from the rest of the continent with its higher-than-average standard of living, and lower-than-average fertility rate. The total fertility rate will fall below the replacement level of 2.1 in South Africa in 2035, in Botswana in 2049, and Namibia in 2071, and they have already been on the receiving end of migration from the rest of the continent for some time.

All these regions escaping the threat of overpopulation and becoming low-fertility countries of at least middle-income levels, sooner or later ending up on the receiving end of transnational migration, is a major game-changing event.

Instead of the pattern of the West (and Japan) versus everyone else, our world right now is in transition to a new one.

Out of major regions, only three, Africa (minus the Maghreb and the southern triad) the Pakistan-Central-Asia axis, and the Fertile Crescent will be left on one side, with a combination of high fertility, low income, risk of overpopulation, and a continuous source of transnational migration, while the rest of the world (except some individual countries such as Yemen or Haiti) will be on the other side, with an increasing chance of escaping the risk of overpopulation, and increasingly finding themselves on the receiving end of transnational migration, but at the same time, sooner or later facing the challenges of an aging population. To be more specific, the population of Asia outside the Fertile Crescent and the Pakistan-Central-Asia axis will not only peak in 2048, and start declining the year after that, but its population has already reached 93 per cent of that peak as of 2023, so even though there will still be some growth till 2048, it will already be minimal. The population of Latin America and the Caribbean, on the other hand, is scheduled to peak in 2056, and start decreasing the year after that. But since in 2023 its population has already reached 88 per cent of that peak, further growth from now on will be minimal there as well.

This transition is about to raise a series of questions: Will migration from Africa find its way to regions such as China, India, Southeast Asia, and Latin America? To a certain extent, it already has, as a sizeable Nigerian community has emerged in Guangzhou, the major port city of South China, and there already is a community of about 17,000 Angolans in Brazil. If these communities have already emerged, more will likely follow as these regions grow wealthier and their populations start to decline, while Africa’s population growth skyrockets at the same time. Regarding the Pakistan-Central-Asia axis, so far the bulk of the migration from Pakistan and Afghanistan has mostly been to Europe and the Gulf States, while the bulk of the migration from Central Asia has been to Russia. Will these trends change, and will migration shift towards China, India, and Southeast Asia instead?

We have already seen some migration from Bangladesh to Malaysia, so such changes may also be possible.

How will newly industrialized, newly aging countries react to the phenomenon of mass transcontinental migration, so far virtually unknown to them? In Northeast Asia, Japan and South Korea have already set a regional precedent with their draconian immigration policies, radically different from those of fellow first-world countries in the West. China seems to have followed a similar course so far, signalled by the even more draconian crackdown on the Nigerian immigrant community in Guangzhou, which forced most of the community to leave the country and reduced its size to a faction of its peak. In Southeast Asia, the wealthy city-state of Singapore with its Chinese majority and strong Muslim minority is relatively welcoming to immigrants from mainland China, while restricting the immigration of Muslims.

Neighbouring Malaysia, on the other hand, with its Muslim majority and strong Chinese minority is welcoming Muslim immigrants

(mainly from Bangladesh and Indonesia), while restricting immigration from China. The new citizenship law of India welcomes Hindu immigrants, and even members of every non-Muslim minority from Bangladesh and Pakistan, but restricts the immigration of Muslims. The Gulf States, as we may have observed for decades, welcome foreign labourers, but only on a temporary basis, without granting them citizenship, or even permanent residence, and often without the possibility of bringing their families with them. Brazil and the rest of Latin America, contrary to strict Asian practices, are relatively open and welcoming, closer to the Western model, and so is South Africa to immigrants from the rest of the continent. Will the strict attitude of Asia, or for that matter, the open attitude of Latin America and South Africa prevail, as their populations start to age, stagnate and decline, and the pressure of immigration increases? Will this newly formed common ground of aging and stagnating, if not declining, populations and an increasing pressure of immigration between the West, Russia, China, Southeast Asia, the Gulf States, Maghreb, South Africa and Latin America lead to some kind of cooperation and coordination among these regions, or, on the contrary, to different policies and a competition between them? Only time will tell, but these regions will need to come up with answers to these questions.

[1] The source of all data in this article is the 2022 Revision of World Population Prospects, issued by the Population Division of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations. URL: https://population.un.org/wpp/