The question in the title may seem peripheral, but it is of decisive importance in Hungarian demographic history. This is when we first read about the number of Hungarians in Hungarian history, thus ending a period of scarce sources. Since the first census was ordered by Emperor Joseph II of Austria and King of Hungary in 1784, researchers have used complex calculations to estimate the country’s population in the Middle Ages, attempting to reach back to the time of the Hungarian conquest in the 9th and 10th centuries.

Of course, we know that estimating medieval army numbers is extremely difficult and uncertain, and even the works of the most distinguished historians contain figures that contradict each other. What is more troubling is that contemporary sources also leave today’s readers in uncertainty, as the figures of tens of thousands and hundreds of thousands found there obviously cannot be taken seriously. There are plenty of examples of this. Around 940, an Arab source estimated the number of attacking Hungarians at 60,000, and they were glad that the 100,000 they thought possible did not arrive. In the West, in 954, they wrote about ‘thousands of leather helmets’, and in 955, according to a contemporary eyewitness account, ‘the Hungarians launched an attack with an army so large that no one alive at the time had ever seen anything like it’. It is not only in the 9th and 10th centuries that we are groping in the dark; the situation did not change until the emergence of pre-modern military bureaucracy in the 16th century.

It is no coincidence that contemporaries favoured large numbers, as it was all the more glorious to defeat an opponent with overwhelming superiority, while the losing side could excuse itself with their superior strength. Another problem is that no contemporary written sources have survived from the Hungarian side, so we have no other choice but to use Western or Eastern sources. Our most important Arab source knows that the Hungarians marched with 20,000 horsemen. Around 920, Arab scholar Jayhānī wrote about the Hungarians based on the accounts of merchants. Jayhānī’s original text has not survived, but we can still read it as an authentic source from Ibn Rusta’s copy from around 930 and the Persian Gardizi’s excerpt from around 1050. According to this, ‘the Hungarians are a branch of the Turks. Their leader marches with 20,000 men.’[1] Modern historians have drawn far-reaching conclusions from the figure of 20,000, believing that it represents the entire population eligible for military service. Assuming 100,000 families of five, they arrived at a total population of 500,000 for the Hungarian people. Others, however, also relying on the figure of 20,000, estimate their number to be only around 100,000–150,000.[2] This can easily lead to misinterpretation, as it is not certain that the figure of 20,000 was based on actual observations, nor is it certain that it refers to the Western Magyars and not the Eastern Magyars who remained on the Volga. The round number itself is suspicious. Among nomads, 10,000 people formed a military regiment, whose Old Turkic term, ‘tumen’, still lives on in the modern Hungarian language as ‘very many’.[3] However, it is not certain that the Hungarian regiment had that many soldiers. The fictitious nature of the number may be indicated by the fact that, according to an entry in the Latin Fulda Annals from 896, exactly 20,000 Bulgarian soldiers were killed in a battle between the Bulgarians and the Hungarians.

‘The debates between Hungarian and non-Hungarian professional and amateur researchers are influenced by the desire to prove national pride’

Of course, knowing the population of the Carpathian Basin would help, but estimating this is currently even more uncertain than estimating the size of the fighting forces. The debates between Hungarian and non-Hungarian professional and amateur researchers are influenced by the desire to prove national pride, and the figures themselves are attributed historical value and political significance. Based on an overview of the nearly 26,000 10th–11th-century grave finds known today, it can be concluded that the Carpathian Basin was sparsely populated, with very small settlements.[4] Of course, it has been suggested that some of the local population joined the raiding parties, which is primarily inferred from the Western coins found among the Moravian finds, obtained through looting. It is logical that if the German princes and Moravian rulers hired the Hungarians as auxiliary troops, then the Hungarians themselves also engaged in this practice.

In the modern era, Hans Delbrück (1848‒1929), a German military historian and the father of modern military history, was the first to attempt to come to terms with large numbers, though by no means definitively. Fortunately, his positive influence can still be felt in specialized works today.[5] In recent decades, Delbrück’s method has been spectacularly supported by the modelling and reconstruction of the logistical needs of armies, the transport of supplies, and travel speeds. Modern calculations have determined the calorie requirements of soldiers, the feed requirements of horses, and the absolutely necessary transport capacity. If we take these calculations seriously, we must bid farewell to the phantom of armies numbering tens of thousands in this era.

Leo VI the Wise, Byzantine Emperor (r. 886–912), wrote about the Hungarians that ‘they are followed by large herds of horses and mares, partly for food and milk, and partly to give the appearance of numbers’. Based on calculations, we can estimate more than 2,700 pack horses for every 10,000 Hungarian warriors, or slightly less, as Hungarian horses were famously undemanding, which reduced transport requirements. Of course, at this point, we have not yet counted the weapons, arrows, and quivers, which would have meant that the above train would have only been able to serve 5,000 people. On the way home, the spoils and the wounded also had to be transported. We rarely read about failures in the area of supplies during the Hungarian campaigns, apart from the 942 campaign in Hispania, when, according to an Arab source, ‘the enemies of God ran out of food and were also short of fodder’. However, the length of the army’s march could not be extended indefinitely: at best, they could only fit two abreast on the roads of the time, and if the end of the column fell far behind, it was at the expense of surprise.

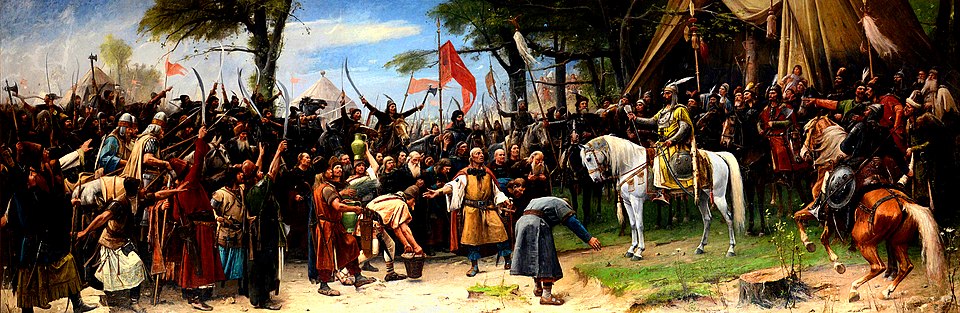

For this reason, the attacking army moved in smaller units in order to advance more quickly. They prioritized mobility over greater numbers, even at the cost of suffering repeated defeats in the West against the Normans and Arabs in places with monasteries and churches, where local militias had already gained combat experience. We can arrive at a similar conclusion if we examine the route and speed of the Hungarian army that appeared during the German rebellion of 954 against King Otto I of Germany. We can conclude that their numbers were modest from the fact that they deliberately did not intervene in the German civil war and only undertook to plunder the target area.

But what do Latin sources say? We have different figures for the four decisive battles of the period. In September 899 at the Brenta River in northern Italy, the Hungarians routed the army of King Berengar I (r. 887–924). Unfortunately, John, the chaplain of the Doge of Venice, only says that the Hungarians came in ‘great numbers’, which can be explained by the large number of reserve horses they presumably brought with them. However, there could not have been very many of them, because they were only able to win by feigned retreat against their presumably much larger opponents. At the same time, there could not have been few of them, as they spent the following winter in Italy, which shows a level of confidence that could only be observed years later in the case of the Normans after their first appearance on the continent.

‘In this period, even the larger Hungarian armies tended to number around 4,000–5,000’

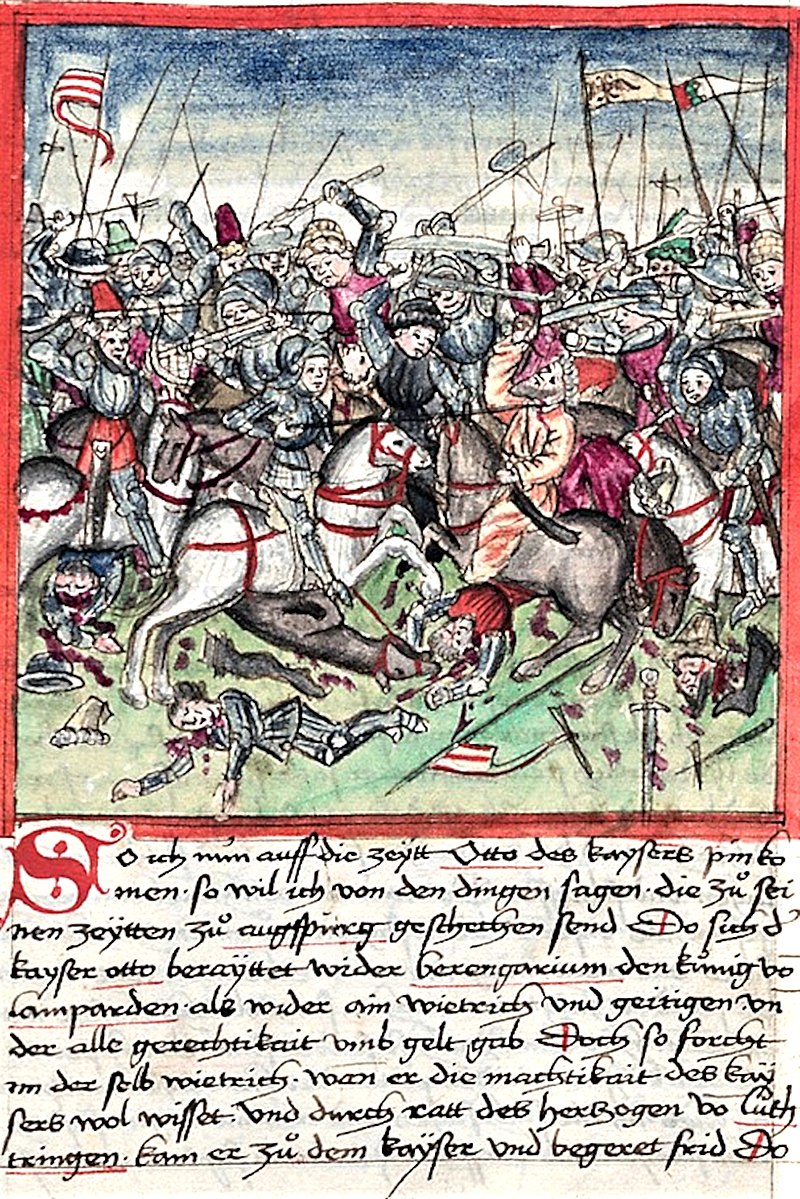

We have no information about the number of troops involved in the next great Hungarian victory, the Battle of Pressburg in 907, nor about the Battle of Riade (Merseburg) in 933, which ended in defeat. In the case of the Battle of Riade, the Hungarians realized during the battle that the Germans had superior numbers and fled. The Hungarian leaders consciously accepted defeat in the battle of Augsburg in 955, knowing that a large German army had gathered against them. The strength of the Hungarian army was confirmed by the fact that they considered the capture of the city of Augsburg possible, although the siege was unsuccessful. The opposing armies may have been of nearly equal strength. It all depends on how large we consider the eight legions of the Germans mentioned in the sources to have been. If the Germans numbered between 4,000 and 8,000, then we can assume that the Hungarian army was of approximately the same size. In this period, even the larger Hungarian armies tended to number around 4,000–5,000.

So far, of course, we have read about the findings of the so-called minimalist school, which follows Delbrück’s line of reasoning. However, there is also a school of thought that uses a radically different method, most notably represented by American researchers Bernard Bachrach and his son David, which calculates figures several times higher than the former, both for Westerners and Hungarians. They assume that military service obligations for free Germans gave German rulers almost unlimited opportunities to increase the size of their armies. These researchers estimate that during the reign of Charlemagne (r. 768–814), the military potential was 100,000, of which 30,000 were heavily armed, but even the Italian expeditionary army of German King Otto II is estimated at 20,000. In their opinion, during the battles of 953–954, German King Otto I moved an army of 20,000 for months and ensured their continuous supply. The American school also adjusts the number of Hungarians to that of the Western armies, and the estimates of tens of thousands recorded on parchment by contemporary chroniclers have thus been transferred to the pages of modern studies.[6]

We do not wish to settle the debate between minimalists and proponents of large numbers. Still, in defence of small numbers, we recall the attack on Berlin by Hungarian Count András Hadik (1710–1790), a field marshal in the Austrian Imperial Army.[7] On 15 September 1757, the idea of invading the enemy’s province of Brandenburg and attacking the Prussian capital arose in Vienna, which Empress Maria Theresa approved on 8 October. Mobilizing the troops was not a problem, as the Seven Years’ War was already in full swing at the time. Fortunately, there is no uncertainty regarding the number of troops, as everything had already been administered. Hadik’s army numbered 3,460 men, including 760 German cavalrymen and 800 Hungarian hussars. They set off from the Dresden–Meissen line on 11 October and, marching at a forced pace, laid siege to Berlin on the 16th, whose population was estimated at nearly 120,000. The city was plundered, and the spoils were taken away that same night on nine carts in cash and bills of exchange. At dawn, they set off again to avoid encountering the approaching relief army. The key elements of the operation were precise planning of supplies, mobility, and surprise. In accordance with Hadik’s instructions, the Hungarian hussars moved around a lot in front of the walls of Berlin to give the impression of a larger army, which was helped by the fact that the officers marched with 3–5 spare horses. This well-documented 18th-century operation sheds light on and explains many aspects of the secret of the Hungarians’ success in the 10th century: even with limited numbers, a well-organized team can achieve significant success in enemy territory against a numerically superior opponent. Yet the Berlin adventure took place at the dawn of the age of mass armies.

[1] Hansgerd Göckenjan and István Zimonyi, Orientalische Berichte über die Völker Osteuropas und Zentralasiens im Mittelalter: die Ǧayhani-Tradition (Ibn Rusta, Gardīzī, Ḥudūd al-ʻĀlam, al-Bakrī und al-Marwazī),Wiesbaden, 2001, p. 68.

[2] György Györffy, ‘Magyarország népessége a honfoglalástól a XIV. század közepéig’, in József Kovacsics (ed), Magyarország történeti demográfiája. Magyarország népessége a honfoglalástól 1849-ig, Budapest, 1963, pp. 45–62.

[3] István Zimonyi, ‘A honfoglaló haderő létszáma’, in László Balogh and László Keller (eds), Fegyveres nomádok, nomád fegyverek. III. Szegedi Steppetörténeti Konferencia, Budapest, 2004, pp. 101–111.

[4] Miklós Takács, ‘The Conquest Period’, in Fifty Years of the Archaeological Institute of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Budapest, 2010, pp. 127–130.

[5] Hans Delbruck, History of the Art of War, Lincoln, NE, 1920, reprint edition 1990.

[6] Bernard S Bachrach, ‘Magyar–Ottonian Warfare. À propos a New Minimalist Interpretation’, Francia, Vol 21, 2001, p. 223; David S Bachrach, Warfare in Tenth-Century Germany, Woodbridge, 2012.

[7] Tibor Simányi, Die Österreicher in Berlin. Der Husarenstreich des Grafen Hadik anno 1757, Vienna–Munich, 1987; Balázs Lázár, Hadik Berlinben. Az 1757-es huszárportya igaz története, Budapest, 2024.

Related articles: