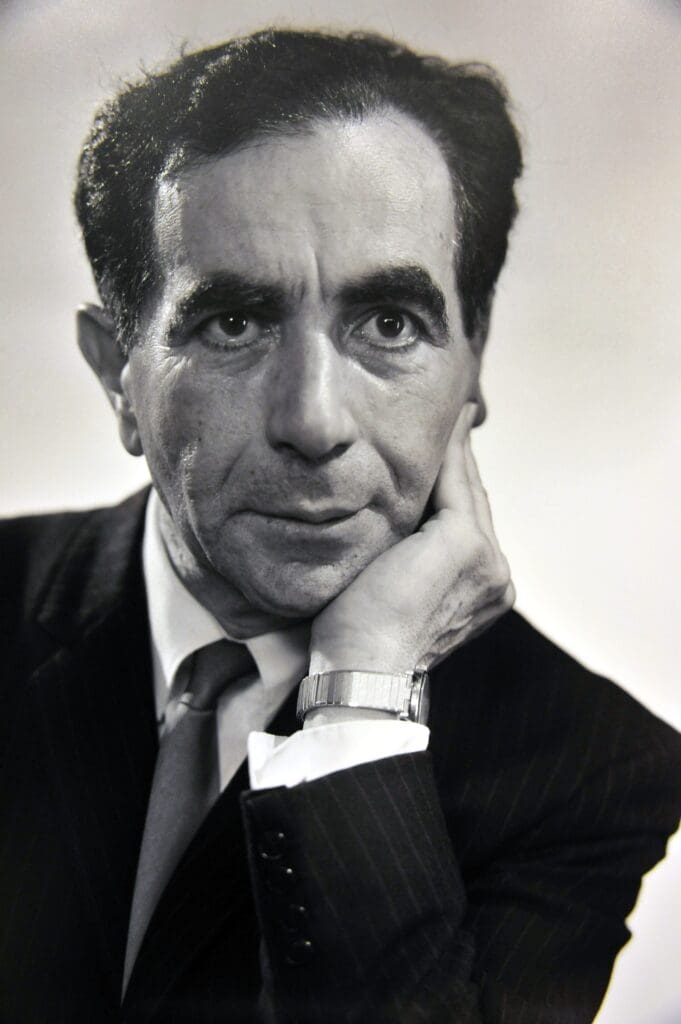

György Faludy is without doubt one of the most original, talented, and controversial Hungarian poets and literary translators. His work is acknowledged but also criticised, on both the right and the left.

Faludy was born on 22 September 1910, in Budapest, in a Jewish family. His original family name was Leimdörfer, and we also know his Jewish name, which was Joseph Dov ben Chayim. His father’s family came from what is Slovakia today (Nagybiccse, today: Bytèa), while his mother came from a well-established Jewish trading family in Western Hungary, the Biringers. After attending the famous Fasori Lutheran Secondary School, he went on to study in Vienna, Berlin, Paris, and Graz. Having seen much of contemporary Europe, he returned home and completed his military service in Horthy’s army as an officer between 1933 and 1934.

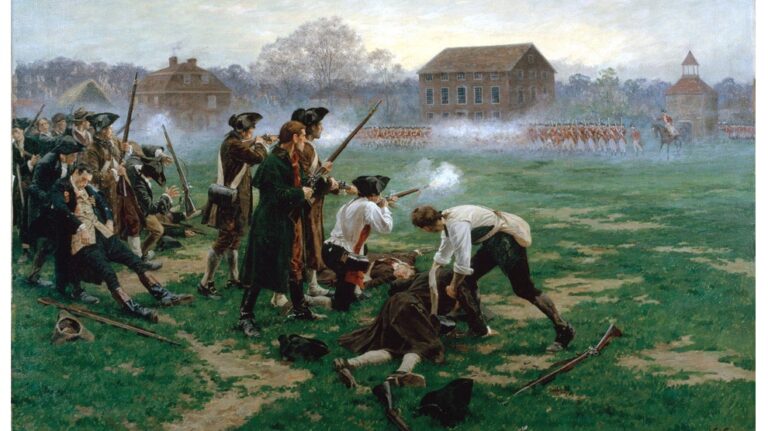

With the ascension of Hitler and Hungary’s shift to the far right, the young poet, who at the time was already famous for his unique reinterpretation of Villon, left for Paris, then Morocco and

finally the United States, even serving in the US Army in WWII.

Many of his relatives, who were left behind, became victims of the Holocaust: many of his mother’s relatives in the countryside, but also his younger sister, while his father died of starvation soon after the liberation of the capital city.

He returned to Hungary in 1946 and found work at the Social Democratic daily Népszava. One of his most controversial actions was his participation in the blowing up of the statue of Catholic bishop Ottokár Prohászka in April 1947. Prohászka was widely seen as a reactionary and an antisemite, even though his thinking was, in economic terms, markedly progressive at his time and he was also somewhat of a Christian Zionist. Another momentum that he recalled as a ‘low point’ in his career was his poem Nyolc szörnyeteg (Eight Monsters), published in Népszava on 25 September 1949, the same day when former Communist Minister for the Interior László Rajk and his associates (among them two Jews, Tibor Szőnyi and András Szalai) were sentenced to death in a show trial. Five other defendants were sentenced to prison—eight people altogether, hence the title, Eight Monsters.

The poem was a savage, frothing, almost maniacal attack on Rajk and his associates. Faludy wrote in several places in the poem of his own animalistic hatred, dehumanizing the politicians he criticized,

rejoicing at their death sentences, which he had obviously been informed of in advance.

In the poem, he likened Rajk, the ‘chief culprit’, to a ‘jackal in a robe’, a ‘murderer’, who ‘confessed coldly and haughtily’. Listening to Rajk, he wrote, he felt that ‘the ancient fish and the cavemen were ‘closer’ to him than the accused Communist politician. In the poem, he likened the accused to ‘eight rotten mummies’, who ‘lived a hundred lives’, but whose lives must ‘end now’.

It is interesting that in the poem, he likened the images of the Second World War, in which Rajk and his associates were also culprits in his view, to a ‘vision from hell’: the next three years of his life he later came to describe also as ‘hell’.

In 1950, Faludy was arrested by the secret police in a Hungarian version of the Stalinist purges, and sent to the ‘Hungarian Gulag’, the concentration camp of Recsk. In his memoirs, titled

My Happy Days in Hell, he likened the forced labour camp to ‘Hitler’s death camps’.

His days were marked with heavy labour, beatings, starvation and suffering. He could not write down his poems, so he memorized them, line by line, repeating ‘a hundred, five hundred, a thousand lines daily. From prison I emerged with a book of poems in my mind,’ he recalled. In September 1953 he was released, with an apology and a threat that he was not to speak of his experiences, or he would face repercussions. Of course, he did speak about them, and his memoirs became a must read not only for right-wing critics of the Communist system but also for disillusioned leftists and liberals.

He left Hungary again in 1956, settling this time in London. There he edited a strongly anti-Communist journal, the Irodalmi Újság (Literary Newspaper). Later, he moved to Canada, where he remained for more than two decades, living in Toronto and receiving Canadian citizenship in 1976.

Today, a square is named after him, the George Faludy Place just across 25 St Mary Street, where he lived for 25 years.

As he put it, he never felt as free in his entire life as when a citizen of Canada.

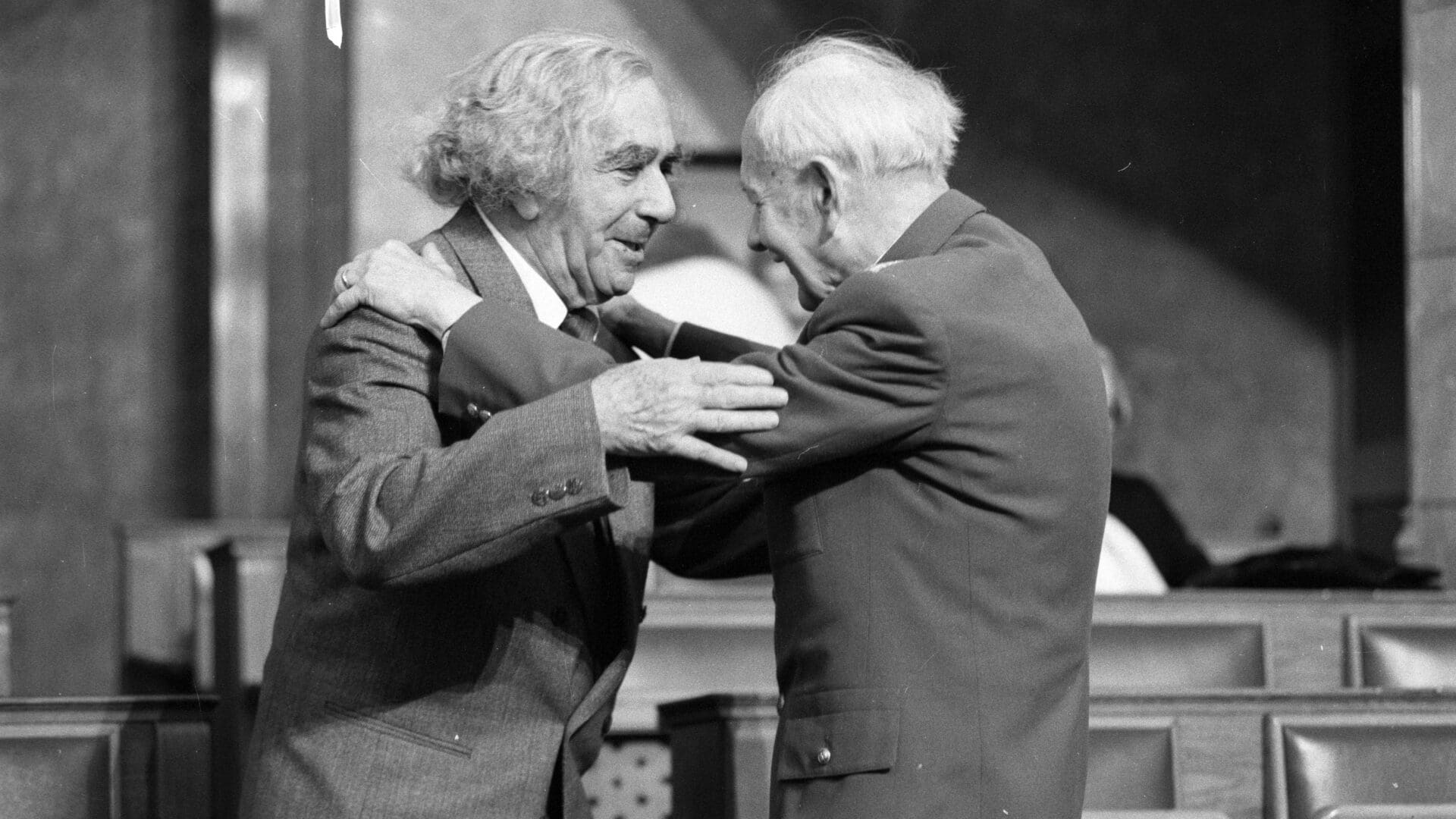

Faludy returned to Hungary in 1989, and was awarded the Kossuth Prize, one of the highest state awards for artistic accomplishments, in 1994.

The poet was also open about his bisexuality. He spent 36 years of his life with a male US ballet dancer in his emigrant years. However, he was also married three times. His last wife, Hungarian Fanny Kovács was 66 years his junior when he married her in 2002. Provoking his critics, who questioned whether real attraction was possible when there was such a huge age gap between the spouses, they published half-naked pictures of themselves—again, a characteristic move for a poet who never really found his place in any system, who sooner or later became a nuisance to everyone, and who, even if sometimes made compromises, always did so provocatively, originally and with talent.