The article is a product of the project titled Conservative Case in Education, supported by the Mathias Corvinus Collegium Learning Institute.

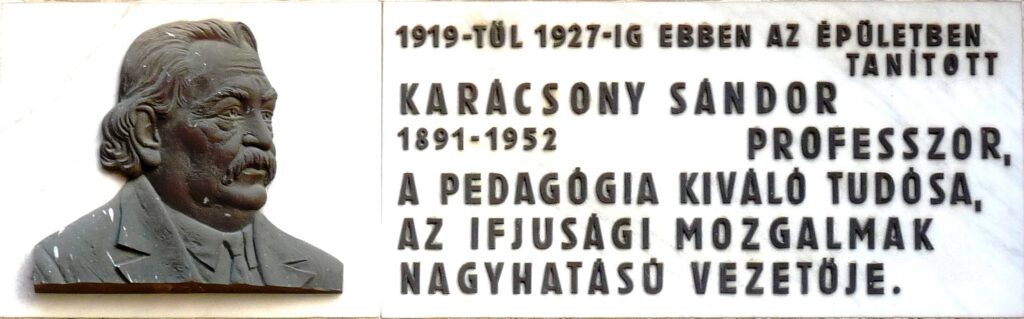

Sándor Karácsony was a pioneering Hungarian educator, scout leader, and cultural advocate whose life bridged the worlds of pedagogy, youth organization, and ethnographic research. Born in 1891 in the Reformed village of Földes, Karácsony dedicated his career to shaping the character and values of young Hungarians—first as a teacher, then as a key figure in the Hungarian scouting movement, and later as a university professor and writer. His work reflected a deep belief in the transformative power of education, cultural identity, and moral leadership. Despite personal hardship and political repression, Karácsony remained steadfast in his mission to nurture a generation grounded in both intellectual rigor and national heritage. His legacy endures as a testament to resilience, service, and a lifelong commitment to Hungary’s youth.

Early Life and Education

Sándor Karácsony was born on 10 January, 1891, in Földes, a flourishing Reformed village in Hajdú County, Hungary. His parents were well-educated; his mother was the daughter of a Reformed pastor, and his father, Zsigmond Karácsony, was a certified agronomist and a well-read, cultured man. Sándor completed his elementary education in his hometown under the supervision of the Reformed College of Debrecen, a prestigious institution that naturally became his next educational step.1

The years spent in Debrecen were pivotal in shaping Karácsony’s future. At the college, he began to hone his skills in youth organization, taking on the role of an elder in the youth congregation. His commitment to education and youth work was evident early on, and he later became a prominent scout leader and the founder of the ‘regös’ scouting movement. His dedication to these causes was deeply influenced by his formative years in Debrecen, where he developed a strong sense of community and leadership.2

‘He played a crucial role in shaping the lives of many young people through his innovative approaches and unwavering dedication’

Karácsony’s influence extended beyond scouting; he was also a respected teacher and writer. His works often reflected his educational philosophy and his commitment to nurturing the youth. His legacy in Hungarian education and scouting remains significant, as he played a crucial role in shaping the lives of many young people through his innovative approaches and unwavering dedication.

In his 1942 work Awakening Hungarians – System of Customs and Pedagogy, he confessed that he had committed to the teaching profession very early on:

‘I was enrolled in Debrecen as a first-year high school student in the fall of 1902. Our first Latin class was from 8 to 9 on 10 September. During the 9 o’clock break, I clearly saw that God had destined me to be a teacher. From then on, I instinctively and consciously prepared for this career. I observed, criticized, pondered, and planned what a person is like if they are a teacher.’3

After completing high school, Sándor Karácsony was admitted to the Hungarian–German department at the Faculty of Humanities, University of Budapest. However, he had to postpone his studies for a year due to mandatory military service, during which he became familiar with the languages of the Austro–Hungarian Empire. His university years were marked by the rise of modern sciences like ethnography, psychology, and comparative linguistics, which profoundly shaped his understanding of humanity and the world.4

World War I disrupted his studies, and in November 1914, he sustained a severe leg injury on the Italian front. This injury left him dependent on crutches for the remainder of his life. Despite this setback, he persevered and, at the end of the war in 1918, successfully obtained his teaching diploma. His determination to continue his education and career, even in the face of such adversity, is a testament to his resilience and dedication.

He began his teaching career during the war at a military high school in Czech territory, despite not having a formal qualification. After the war, he moved to Kassa and later to Budapest, where he joined the faculty of the Royal Hungarian State Miklós Zrínyi High School at 17 Tavaszmező Street in the eighth district. Alongside his teaching duties, he quickly became involved in organizing youth activities. In the 1920–21 school year, he served as the teacher president of the school’s self-education circle and founded the high school’s scout troop, becoming its leader.5

Karácsony and the Boy Scouting Movement

Sándor Karácsony became involved with scouting through his acquaintance with Béla Megyercsy, who introduced him to the Hungarian organization of the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA), known locally as the Christian Youth Association (KIE). This connection marked the beginning of Karácsony’s deep and lasting involvement in the scouting movement. As the leader of his high school scout troop, he quickly became a prominent figure in Hungarian scouting, which was rapidly expanding its presence across the nation.6

Karácsony’s leadership and organizational skills did not go unnoticed. He played a crucial role in the development and strengthening of Hungarian scouting, contributing significantly to its growth and influence. For eight years, during the presidencies of Sándor Sík and later Béla Vitz, he served as co-president of the Hungarian Scout Association. In this capacity, he was instrumental in shaping the direction and policies of the organization, ensuring that it remained true to its core values while adapting to the changing needs of Hungarian youth.7

‘He sought to inspire and educate young people, providing them with the tools and knowledge they needed to become responsible and engaged citizens’

Beyond his work with the scouts, Karácsony was actively involved in the leadership and formation of numerous Protestant youth organizations. His commitment to youth development and education was evident in his editorial work for the magazine Erő (Strength),8 published by the Hungarian Evangelical Christian Student Association, and the book Hungarian Youth.9 Through these publications, he sought to inspire and educate young people, providing them with the tools and knowledge they needed to become responsible and engaged citizens.

Karácsony’s influence extended beyond the confines of the scouting movement. He was a passionate advocate for the integration of folk culture into youth education, believing that a strong connection to one’s cultural heritage was essential for personal and communal development. This belief led him to collaborate with musicologists Lajos Bárdos and Károly Mathia in compiling the volume 101 Hungarian Folk Songs, which aimed to replace the often dubious-quality, military song-based repertoire frequently sung by scouts with collected masterpieces of Hungarian folk culture.10

The Ethnographic Contributions of Karácsony

Sándor Karácsony’s contributions to Hungarian scouting and youth education were profound and far-reaching. His work with the YMCA, the Hungarian Scout Association, and various Protestant youth organizations demonstrated his unwavering commitment to the development of young people. Through his leadership, editorial work, and advocacy for cultural preservation, he played a pivotal role in shaping the future of Hungarian youth, ensuring that they remained connected to their heritage while preparing for the challenges of the modern world.

During high school excursions and camps, Sándor Karácsony frequently visited his native region with his students to conduct ethnographic surveys. He actively involved young people from the capital in these research activities, introducing them to the daily lives and traditions of rural communities. Karácsony firmly believed that ‘Scouting is not an educational method but a life enterprise,’ a philosophy that guided his approach to youth education and development. Despite his innovative methods, his activities were often met with skepticism by the national scout leadership.

‘Scouting is not an educational method but a life enterprise’

Karácsony’s deep commitment to preserving and promoting folk culture is evident in his collaboration with musicologists Lajos Bárdos and Károly Mathia in 1929, as mentioned above. Their work 101 Hungarian Folk Songs was a testament to his dedication to integrating cultural heritage into the scouting experience.

His passion for ethnographic research and folk music collection eventually led to the initiation of the regös scout movement, which sought to preserve and celebrate Hungarian folk traditions through scouting activities. Although Karácsony stepped back from active involvement in scouting from the mid-1930s, he remained closely connected to the movement and continued to influence its direction through his academic work.

Academic Life

Karácsony devoted much of his time to academic research, particularly in the fields of educational science and social psychology. He also joined a committee working on an etymological dictionary to systematize the vocabulary of the Hungarian language. In 1934, he became a professor at the University of Debrecen, a position he accepted partly due to professional disagreements with his mentor and colleague, the Piarist monk and state secretary Gyula Kornis.11

Throughout his career, Karácsony remained dedicated to the principles of education, cultural preservation, and youth development. His work left a lasting impact on Hungarian scouting and education, and his legacy continues to inspire those committed to these fields. His efforts to blend academic research with practical applications in youth education and cultural preservation have made him a respected figure in Hungarian history.

Sándor Karácsony only actively returned to Hungarian scouting after World War II. He initially served as the honorary president of the reorganizing Scout Association and later became the president of the Hungarian Democratic Scout Association. However, the political landscape changed dramatically after the communist takeover in 1948. Karácsony’s Christian beliefs and humanistic ideals clashed with the new regime’s ideology, leading to his exclusion from teaching and public life.12

Late Years and Exile

As a result, Karácsony spent his final years in voluntary exile, retreating to his hometown and his summer house in Balatonakarattya. Despite being marginalized by the authorities, he remained committed to his principles and continued to influence those around him through his writings and personal interactions. His dedication to education, youth development, and cultural preservation never wavered, even in the face of political oppression.13

Karácsony passed away in Budapest on February 23, 1952.14 His legacy, however, endures through the countless lives he touched and the lasting impact of his work in Hungarian education and scouting. His life story is a testament to the power of resilience, conviction, and the enduring importance of cultural and educational values.

The article is a product of the project titled Conservative Case in Education, supported by the Mathias Corvinus Collegium Learning Institute.

- ‘Karácsony Sándor’ in Ágnes Kenyeres (ed), Magyar Életrajzi Lexikon, Budapest, Akadémiai Kiadó, 1967–1994, https://mek.oszk.hu/00300/00355/html/, accessed 12 Dec 2024. ↩︎

- Ferenc Gergely, A magyar cserkészet története 1910–1948, Budapest, Göncöl Kiadó, 1989, p. 127. ↩︎

- Sándor Karácsony, Ocsudó magyarság, Budapest, Exodus Kiadó, 1942, pp. 9–10. ↩︎

- ‘Karácsony Sándor’ in Ágnes Kenyeres (ed), Magyar Életrajzi Lexikon. ↩︎

- Ferenc Gergely, 1989, pp. 79–80. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid, p. 111. ↩︎

- Ibid, pp. 79–80. ↩︎

- Sándor Karácsony, Magyar ifjúság, Budapest, Exodus Kiadó, 1946. ↩︎

- Ferenc Gergely, A magyar cserkészet története 1910–1948, p. 111. ↩︎

- Sándor Komlósi, ‘Karácsony Sándor a debreceni katedrán’ in László Brezsnyánszky (ed), A ‘Debreceni Iskola’ neveléstudomány-történeti vázlata, Budapest, Gondolat Kiadó, 2007, pp. 190–193. ↩︎

- Ferenc Gergely, A magyar cserkészet története 1910–1948, pp. 353–354. ↩︎

- Ibid, p. 382. ↩︎

- ‘Karácsony Sándor’ in Ágnes Kenyeres (ed) Magyar Életrajzi Lexikon. ↩︎

Related articles: