Today, Antal Schütz’s book Hungarian Vitality (Magyar Életerő)[i] would most probably be called a brave or even reckless endeavour. Why? Because his candid approach to Hungarian virtues and fallibilities would instantly shock both political sides. Anti-nationalists and non-nationalists (here meaning those whose loyalty to the nation does not come first) would get upset about the virtues. By contrast, nationalists would be outraged or might even call him a traitor for describing Hungarian fallibilities. Fortunately, Antal Schütz does not seem to have cared about the taboos which were also prevalent in his time, for he was uncompromisingly determined to find the essence of Hungarian vitality.

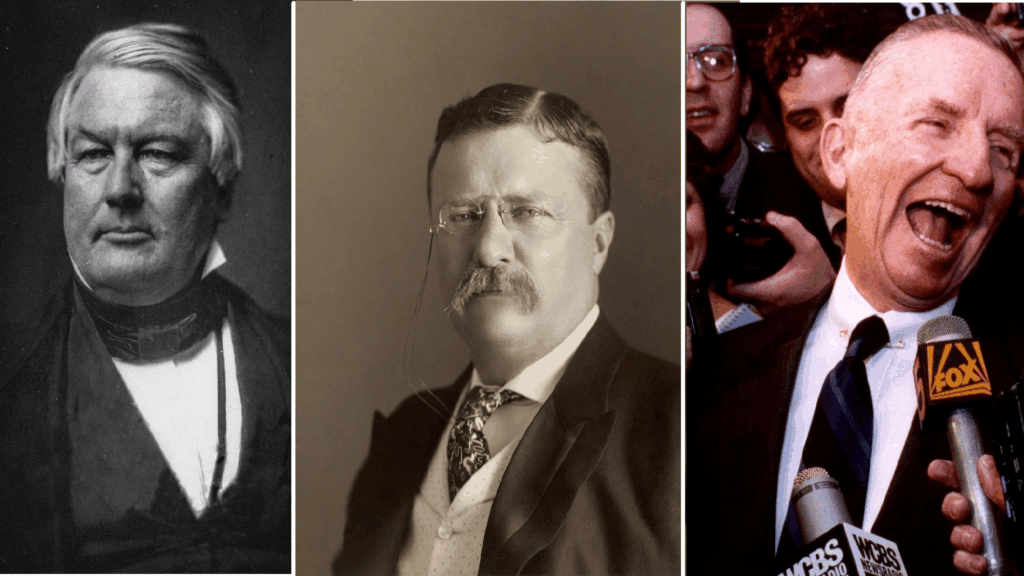

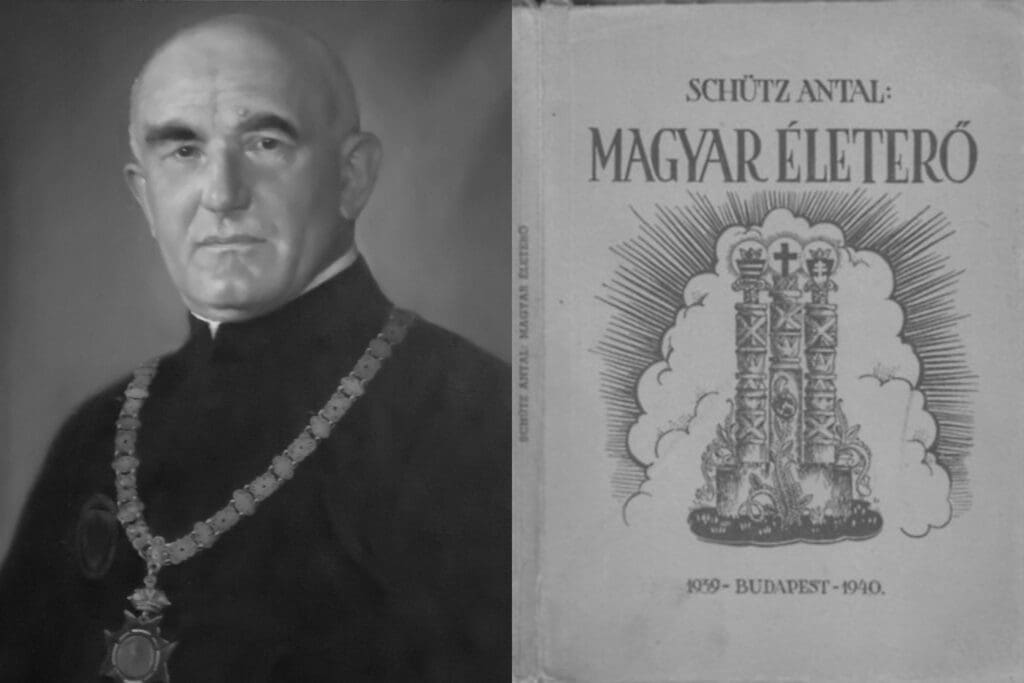

Antal Schütz (1880-1953) was a Hungarian Roman Catholic priest, a member of the Piarist order, a university professor at the Pázmány Péter University, and one of the most outstanding Hungarian theologians of the 20thcentury. His numerous writings, including books on dogmatic theology and saints were familiar to contemporary Catholic readers. He also wrote acclaimed monographs and edited the works of Ottokár Prohászka, one of the most famous but—due to his antisemitism—also one of the most controversial figures of Hungarian church life in the 20th century.[ii] In this article, we will review his book entitled Hungarian Vitality, which was published as the first volume of a book series for the youth, but which, as explained in its introduction, was also recommended for the whole nation and those responsible for the youth: parents, educators, and leaders. The central aim of this review is to present Schütz’s ideas that can still serve as guiding principles for Hungarians and Hungarian politicians in the 21st century.

The year of the publication, 1939, is indicative, but it should be noted that the book itself is a collection of Schütz’s earlier writings as well as his lectures and radio speeches from 1933 to 1939. After a fascinating introductory chapter on the writer’s fondness of books (which already presents his poetic skills and how well he is read in both Hungarian and international literature), two main topics are treated: Christian religious ideas and the question of Hungarian national development; this review will elaborate on the latter.

No less than a new state foundation is necessary

The political, social, economic, and cultural ‘path seeking’, which began after the First World War, continues in 1939 and poses new challenges for Hungary—Schütz begins his treatise. No less than a new state foundation is necessary, he declares. In order to understand where to move forward, first, we must look at our past, our history, so that we become able to identify our strengths, weaknesses and our spiritual resources. ‘Of course, you cannot help those who cannot or do not want to read the book of history,’ Schütz writes.[iii] After taking this initial step, we Hungarians will be able to define our mission and the strategies necessary to accomplish the task.

Many of us would say that pessimism is one of the main characteristics of the Hungarian people, but not Schütz. Naturally, he recognises that we do have a tendency towards pessimism, as has been the case—in different ways—with many of our great national literary and political heroes, including Mihály Vörösmarty, István Széchenyi, Imre Madách, and Endre Ady. Would we, Hungarians, have good reason to be pessimistic? Of course, we would! The lack of brother nations, the unique situation of being caught between the West and the East, economic and social problems, and our political and historical tragedies can certainly generate a negative outlook. It is enough to look at our history, including the 150-year-long Turkish occupation of Hungary from which we had still not fully recovered, to understand why—wrote Schütz in the 1930s.

Yet, if we use such a narrow scope, we miss half of our historical past. The fact that we are still present in the flow of human history as Hungarians—and have been for a thousand years—proves that a remarkable vitality revives this nation from time to time. Schütz also highlights the force of Hungarian assimilation as proof of national greatness (which he experienced having been born in Kistószeg (today Novi Kozarci n Serbia), a village inhabited by ethnic Germans at the time). He concludes that pessimism is present in Hungarian history, but it is the consequence of either a biased historical analysis or a projection of an unfavourable phase in the nation’s life. In short, Hungarian characterology does not include pessimism, Schütz argues, but even if it did, it should not be applied in matters of national concern. Pessimism is not a helpful guide; it deceives us, since it prevents the accurate analysis of historical details and immobilises individual and social action, so it stands in the way of national growth.

Then, what are the frailties of Hungarians? Schütz mentions two central attributes. First, we have more affinity for reverie than we should. Being able to create grand visions is necessary, but it is temptation to inaction. Hungarians tend to daydream or imagine certain situations and outcomes without investing any energy in action. Once this phase is overcome, an ‘explosive manifestation occurs in the force of action’,[iv] but this process is too slow, and we are inclined to start moving too late. Second, Hungarians often prefer to avoid hard work. Our ‘double or nothing’ attitude sets us apart from many other nations. Hungarians lack the discipline to work on a regular schedule and are characterised by work avoidance. In our minds, acquiring certain goods is more effortless than producing them, Schütz suggests.

Is Schütz being anti-Hungarian with this criticism? Of course, he is not. Is he formulating factual arguments? More thorough psychological and sociological research should probably need to be conducted to answer this question correctly. Still, the idea we should focus on is that—even if we cannot provide a hundred per cent accurate answer—these arguments seem to be plausible to describe certain human (and especially Hungarian) behaviour, and they indeed hamper the development of national growth. Schütz argues that these factors should be considered when we devise our national plans.

Beyond these specific conclusions related to Hungary, Schütz also underscored that the final prerequisites for any nation’s future, for its greatness, are ‘national public spirit, national self-respect, and national capacity of action’. And what else is necessary? A healthy national leadership, whose tasks are divided into two main spheres: politics and national education. Politics is short-sighted; the politician’s duty is to act in the present and—based on the situation and the resources available—to represent economic, social, administrative, and cultural ideals demanded by the nation’s prosperity. Educators, on the other hand, focus on long-term goals; their activities are defined by ethical standards.

The professional political leader is also a national educator

Obviously, these two fields are interconnected. The professional political leader is also a national educator since —by interpreting the historical vocation of the nation—he provides content and support for national self-consciousness and self-confidence. At the same time, proper national education paves the ground for political achievements. Schütz warns that disagreements or conflicts between politicians and educators about the nation’s mission must be avoided. Although he refers to historical facts, it seems that it is the clergyman speaking when Schütz concludes that a nation’s greatness cannot be reached without faith, and faith can only be preserved by the Gospel.

One of the reasons why Hungary does not flourish is the lack of a proper aristocracy—Schütz argues. For Schütz as a theologian, aristocracy means the very best of a nation, with no particular class attributes. In order to overcome this deficiency, more emphasises needs to be placed on the education of the national elite. It is not enough to do away with individualism, Schütz stressed, but the healthy renewal of the community principle is also indispensable. While some reforms are required in order to build an efficient education system, making everything simple does not contribute to growth: there must be obstacles for the genius to break through. Schütz highlights four great Hungarian heroes as examples: Péter Pázmány, Miklós Zrínyi, István Széchenyi and Ottokár Prohászka. Although they were different, what connected all four is that they were all continuers of St Stephen’s legacy. The author also provides a brief and instructive summary on the genius of Pázmány and Prohászka, and on their personal traits that allowed them to rise above other Hungarians.

A review of a book must always be selective. In this one, Schütz’s arguments related to the possible ascension of the Hungarian nation are discussed in greater detail than his Christian reflections and his insightful analyses of the broader historical developments of his time (e.g., the rise of Nazism and bolshevism).

Schütz was a man of his times, and he was not free from the limited perspective of the times he lived in (none of us is). It is conspicuous that he only discussed male heroes (he explicitly wrote that the nation needed men[v]); based on this writing, his attitude towards democracy is not evident (at one point, he condemningly notes that some have replaced God with the ‘idol of freedom called democracy’[vi]); and he also praises the controversial Prohászka to an extreme extent. But of course, it does not follow that Schütz was misogynous, anti-democratic, or antisemitic. On the other hand, this book is an invaluable guide, showing what virtuous patriotism is. The way Schütz narrates his story is an excellent demonstration of how people may be organically connected to their nation and at the same time maintain an honest and critical approach in their analyses of that same nation, even if the facts described may be distressing. Every Hungarian politician should adopt this essential attitude, or at least try to do so.

[i] Antal Schütz, Magyar életerő, Budapest, Korda R. T., 1939

[ii] László Bernát Veszprémy wrote four articles on Prohászka for Hungarian Conservative online, available at: https://www.hungarianconservative.com/?s=proh%C3%A1szka. As a seminarian, Schütz attended spiritual exercises led by Prohászka, and met with him personally several times (Zoltán Sármási, ‘Schütz Antal életútja az önéletrajza tükrében’, Egyháztörténeti Szemle XXI/1, 2020)

[iii] Schütz, Magyar életerő, 41.

[iv] Schütz, Magyar életerő, 17.

[v] Schütz, Magyar életerő, 105.

[vi] Schütz, Magyar életerő, 75.