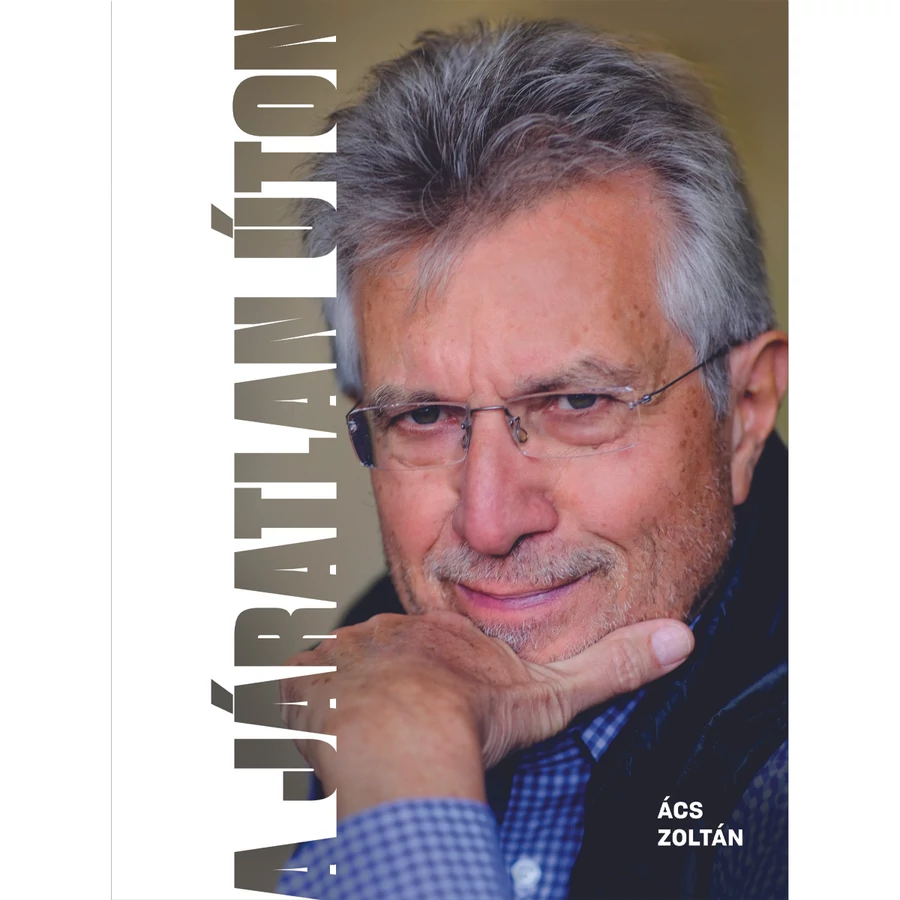

A memoir by Zoltán Ács, an internationally renowned professor of economics and member of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences (HAS), has recently been published. This book captures his journey from a refugee camp in Austria to the U.S. and later, back to Hungary, reconstructing various stages of his life, from pre-war Hungarian high society to absolute poverty in a Cleveland ghetto, followed by his international professional recognition, HAS membership, and more. An integral part of this ‘road less traveled’ marked by multiple struggles is the understanding and re-evaluation of his Hungarian family heritage.

When I began reading the English manuscript received from MCC Press a year ago, I wasn’t convinced whether I should work on it. I was very grateful for the opportunity, but the text left me confused. By then, I had already lived in the U.S. for two years, and was actively involved in the North American Hungarian diaspora community and had written about Hungarian Americans (over 200 articles, including nearly 100 in-depth interviews). My interviewees were proud of their Hungarian roots, language, and cultural heritage, and they passionately served the local Hungarian communities and the local, state, or nationwide organizations that their ancestors or themselves had established.

In contrast, Zoltán Ács—born in an Austrian refugee camp to a family with a rich Hungarian cultural heritage (noble and educated ancestors and parents who were deeply committed to the Hungarian cause), who later ended up in the projects in Cleveland, OH—experienced his Hungarian identity more as a burden during his childhood and youth. He dropped out of high school to help his family financially, and as a teenager, a young adult, and even later as an aspiring economist, he still struggled to value his Hungarian heritage. At one point, he even changed his name from Zoltán to Joe, using the English version of his middle name. Though he maintained contact with relatives in Hungary, he only began to truly appreciate his Hungarian roots decades later, during the rapid ascent of his professional career, at the time of establishing and benefiting from professional ties in Hungary.

Despite my initial doubts about the manuscript, I accepted the challenge—not only because I was asked and supported by MCC Press’s director Tamás Novák and chief editor Anikó Gorácz—but also because, during our first personal meeting in Budapest, I met a kind, engaging, cheerful, yet somehow melancholic professor. I quickly realized that my concerns were about the content and style of the manuscript, and not about the author himself. His journey along the road less traveled is admirable and exemplary, both personally and professionally. My job would be to find the missing pieces and make the text and his journey understandable and engaging for Hungarian readers living outside the North American Hungarian diaspora, as well as those outside his professional field.

‘During our first personal meeting in Budapest, I met a kind, engaging, cheerful, yet somehow melancholic professor’

Before I could revise and supplement, or sometimes even re-write the raw Hungarian translation of the memoir received somewhat later from MCC in my role as creative editor, I had to understand Zoltán’s unusual path—especially in comparison with my earlier diaspora interviewees—along with his personal and professional thoughts, motivations, and accomplishments. My background in economics and journalism, my more than two years spent in the U.S. (including familiarity with the Hungarian community in Cleveland), my interviews with Hungarian diaspora community leaders as well as my additional research about the author’s father—Vitéz Imre Ács, born in Bácsalmás, Hungary, who was very active in three Hungarian organizations in Cleveland simultaneously—all helped immensely.

During our several days of long and often cheerful, though sometimes argumentative, conversations, I had to first understand how the author evolved from a conflicted childhood relationship with his father to mutual recognition and reconciliation. Also, starting out from the Cleveland projects, how did he become a renowned professor of economics and researcher at prestigious American universities (Sangamon State University, Merrick School of Business, Mason University, etc.), public institutions (U.S. Small Business Administration, etc.), and projects and institutes (GEM, KSTE, REDI, etc.) and later a member of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences (HAS), the Association of Hungarian American Academicians (AHAA) and the Friends of Hungary Foundation (FHF), a guest lecturer at MCC, and founder-director of the Vienna Institute for Global Studies (VIGS). Finally, I had to understand why he said that his first 50 years had been defined by constant struggle and deep fear of backsliding, and why only around the age of 70 did he feel ready to share publicly these details of his turbulent personal and professional life, when not only did he begin to take pride—in addition to his professional accomplishments—but also in the previously hidden (or even felt shameful) details of his journey and in the role that his Hungarian familial and cultural heritage played in this success story.

A section from the Foreword:

‘As I was writing this memoir, I realized how much we had lost because of the war, and how we arrived in the New World from Hungary with absolutely nothing. During the war, my family lost all of its wealth and money, so we set out with no financial capital. Nor did we have much social capital: in Cleveland, our connections were mostly limited to other Hungarians, primarily my father’s, who for a long time didn’t like Americans, even looked down on them, and refused to adapt to them, let alone integrate. My mother, on the other hand, was more open: she chatted with the neighbors, took piano lessons, and later gave lessons herself. But all of that meant very little to me as a teenager…

What the family did preserve, however, was cultural capital—and that is what most fundamentally defines people: their faith, their language, their history, their eating habits, and their heritage. But what is all that worth thousands of miles away from a homeland that has become a war-torn, defeated country? While my parents clung desperately to their Hungarian cultural heritage, I increasingly saw it as narrow and confining. The kids I met in America—on lower Buckeye Road in Cleveland, and later on in the projects—had no idea what being Hungarian even meant. They knew we were refugees, and they were generally friendly toward us, but living among them and making friends with them made me want to be like them. When you’re already looked down on for living in the ghetto, your only real option is to blend in—breaking out, especially as a child, simply isn’t possible.

Since we only lived on Buckeye Road, near the Hungarian community, during my earliest years, I didn’t recognize the value of the cultural capital my parents had brought with them, lived by, and represented—including their deep respect for education, knowledge, and learning. Yet those were exactly the “springboards” we desperately needed as penniless immigrant children in a project in order to cross the “abyss” and eventually regain or reclaim the various forms of capital—social, human (professional), and financial—that we had lost in the war and during immigration.

‘Given the circumstances, my parents probably couldn’t have done more for me than they did’

As a teenager, I didn’t understand any of this, just as I didn’t grasp how much my family heritage and my parents influenced my life. My parents, however, understood it well. However, my father never spoke to me about such things. In fact, at one point—when I dropped out of high school and started working to help my mother—he gave up on me altogether. My mother, though, never stopped insisting that I continue my studies. It would have been very easy for me to never finish high school—or, if I had, to never go to college. I could have remained a steel mill worker, married a Puerto Rican or “hillbilly” girl from the projects, or even ended up in jail, like so many young men in the ghetto. My mother saw all this clearly, and she tried her best to guide me in the right direction, though at the time, I didn’t always understand her, and of course, often disagreed with her. For example, I didn’t see why I had to come home for dinner, why I couldn’t stay out on the streets until late at night. Given the circumstances, my parents probably couldn’t have done more for me than they did.’

Just like with my previous book’s subject, Pál Szekeres—a father of three, Olympic bronze medalist, and triple Paralympic champion fencer—I found myself being more interested in the personal aspects, while they tended to focus on the professional narratives and accomplishments. Nevertheless, the intertwining of personal and professional lives is so rich and eventful that the respective books are worth reading and reflecting on to the general public—these appeal not only to athletes or sport diplomats, but also to economists and researchers interested in small business.

I’m very grateful for being able to contribute with both my professional knowledge and my own diaspora experience to this memoir. Though I am ‘only’ its creative editor, in terms of my enthusiasm, dedication, and effort, I feel like I was a co-author, too. I warmly recommend this book to anyone interested in the Hungarian diaspora in North America and/or in small business economics, regardless of their location, age, or profession.

Related articles: