This article was originally published in Vol. 5 No. 4 of our print edition.

Read as literature, the annals of liberal-progressive apologia may have a utopian ring, but lately the genre has grown to mimic a historicized cautionary tale, rife with the fall from grace, the eleventh hour, and the point of no return. Blending the nineteenth-century children’s book with Genesis 2–3, its moralizing refrain tells of warnings that backward electorates once failed to heed, edicts they irrationally flouted, and the grisly detail of the offender’s fate: a mix of autocracy, chaos, and ruin. Parallels to Hitler, the January 6 storming of the Capitol likened to the Reichstag aflame, or peace in Ukraine analogized to the Munich agreement of 1938, all attest to this heuristic. Every such analogy, simile, or extrapolation carries a last warning. Every failure to reaffirm the creed is a corner turned on the road to illiberal dystopia. While these recourses are hardly novel per se, they may at times become ripe for rediscovery. They often draw on untapped recesses of history as fresh challenges arise to the incumbent ideology.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine seems to have brought about such a stimulus. Filtered through moral binaries, it has put the liberal imagination on a martial footing, pushing sense-making narratives of combat in a hunt for new legitimizing precedents. To the extent military aid remains conditioned on voting outcomes amongst Ukraine’s allies, these retrospective quests come folded into the elitist scolding of electorates that has become liberalism’s operating software since around 2016. Yet besides lumping in Ukraine sceptics with the bogeyman of right-wing populism, Western liberals have coped with the singular return of war to Europe in new ways—more tragic, yet more ambitious. Amid the failure to roll back Russia, they have subsumed a discourse that once belonged farther to their left—to their illiberal, revolutionary, and even repressive left.

Spain’s experiment in the 1930s had long supplied fodder for self-styled anti-fascists. In rallying to the Second Republic’s defence as it withstood Franco’s nationalist uprising of 1936, far-left revolutionaries, both foreign and domestic, warned in vain of fascism’s violent advent, three years before the wider outbreak of war in Europe. Abandoned by liberal democracies but undaunted, they put their lives on the line to defend a besieged ‘democracy’, thus proving the neutrality of bourgeois-led powers a cynical imposture. Franco’s takeover meant defeat, but also vindication: liberals had been warned.

Such was, for close to a century, the exclusively leftist tale of the Spanish Civil War. But Russia’s invasion has supplied a radically new frame to apprehend the events of 1936–1939, unburdened by the weighty legacy of Bolshevik allegiances amongst the anti-Francoist camp. It is a frame that Western liberals—habitually keen to police historical distortion and fabrication—have not failed to seize on.

The shift was presciently signalled, of all people, by Russia’s punk-rock wunderkind, striking a note that hostilities in Ukraine a decade later would amplify into a chorus. In July 2012, Nadya Tolokonnikova walked into a Moscow courthouse, NO PASARÁN emblazoned on her t-shirt, mid-way through the trial that would land her band, Pussy Riot, two years in jail for ‘anti-religious hooliganism’. The act had stormed the city’s cathedral, clad in neon balaclavas and tights, to perform ‘Mother of God, Drive Putin Away’ before the autocrat’s sham re-election that year. The Orthodox Patriarchate found the wry lyrics blasphemous and sued. A call to arms as the fascist enemy closed in, the slogan ¡No pasarán! (They shall not pass!) was first uttered by communist firebrand Dolores Ibárruri at the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, and embraced by Republican militias during the long Siege of Madrid. The city’s fall in March 1939, ushering in Franco’s victory and 40-year regime, infused the slogan with its timeless meaning as vindication in failure; not unlike the spirit in which Tolokonnikova, smiling lips puckered, left that day’s hearing, her raised fist matching the yellow-on-purple fist on her chest.

‘Russia’s invasion of Ukraine seems to have brought about such a stimulus’

Odd bedfellows flocked to defend her, too. Born two days before the Berlin Wall fell, Tolokonnikova was ahead of the curve in repurposing red 1930s memorabilia for end-of-history liberal aims. Pictures of the trial soon went viral across the global press. Clothing marketed with ¡No pasarán! ran out of stock within hours. Pussy Riot was quick to bask in its newfound role as an icon that radical leftists and centrist liberals could both cohere around, inside, and outside of Russia. In early 2014, when Moscow’s Gogol Center was banned from screening A Punk Prayer, HBO’s special about the judicial saga, the band stated: ‘This project now lives separately from us, in many different forms, across the world.’1 Charlotte Fereday, a Hispanist at King’s College London, stressed Putin’s repression as the reason why ¡No pasarán! suited Pussy Riot’s moment so well. Nearly a century apart, Fereday argued, Russia’s pro-democracy movement had converged with Spain’s Republicans in ‘affirmative failure in the face of repressive rule’.

Since February 2022, utterings of the slogan have continued to multiply, as if vindictive defeat now loomed over Ukraine’s Eastern battlefront. Early in the war, civilians were heard2 in Kyiv chanting it while helping soldiers build a barricade, as the younger Euromaidan protesters had done back in 20143 in the capital’s nearby square. Hoodies branded with Zelenskyy’s warrior pose, the flag, and ¡No pasarán! underneath have sold online worldwide since the invasion. Google recorded a spike in use of the phrase in both scholarly and popular sources. Reddit chatrooms have dwelled on the historical likeness between the two armed conflicts. Countless op-eds in multiple languages keep being penned to whip up pro-Ukraine sentiment with reference to the romantic fate of the anti-Francoist fighters defeated nearly a century ago in Spain.

No single voice stands behind the ubiquitous analogy. Far-leftists who happen to support the global blob’s pro-Ukraine policy, though often drowned out by the louder voices of anti-militarism and NATO-scepticism, are doubtless keen suppliers of Spanish-Republican semiotics. John Feffer of Democratic Socialists for America and the Open Society Foundations, to name one, wrote in the war’s first month that ‘Putin is the Franco of today, and Ukraine must become the graveyard of Putinism’, likely another nod to a Republican catchphrase impelling militiamen during Madrid’s siege to make Spain’s capital the ‘graveyard of fascism’. Voices on the pacifist left, though—not least a mosaic of hardline Spanish communist parties4—have abhorred this repurposing of Republican lore as crassly opportunistic, decrying its over-extension of the legitimizing potency of anti-fascist sacrifice beyond the defence of Ukrainian sovereignty and into a global conflagration of capitalist self-interest.

Meanwhile, as the war has ground on to no discernible end and fatigue has snowballed on the left, pro-Ukraine centrists and right-liberals with no prior stake in Republican memory have emerged as the chief agents of the appropriative recycling. It mostly started with intellectuals—as high-minded fancies of this sort often do—before trickling downwards into popular cliché. At times, the echoes and evocations have even come detached from their contextual relevance in the Ukraine war to take on larger meanings amidst the travails of global liberal institutions and norms. Alberto Alemanno, to name one such ivory-tower pacesetter of transatlantic renown, is an impeccably credentialed Italian scholar of EU law. Channelling his milieu’s hysteria at the time, his social-media rallying cry in response to JD Vance’s speech at the Munich Security Conference in February this year was also… no pasarán. Elaborating on what he hoped Brussels would go to war before letting pass—the perimeter of his own figurative entrenchment—Alemanno did not summon Europe’s proletariat to a sacrificial revolution against Trumpism. But his liberal hill-to-die-on did not lack the unmistakable resonance of an anti-fascist cri de guerre either: ‘The EU stands in the way of the emergence of the new cultural hegemony, presented as a remnant of an old non-zero-sum world governed by respect of rules, a spirit of solidarity, and beliefs in humanity and progress as a force for good.’5

Far from any pushback against the uncontextualized recovery of Bolshevik propaganda by a Jean Monnet Chair in EU Law, the only genial challenge to Alemanno’s message ran in reverse. One former Green Euro-MP quipped in reply that he wished those had been Ursula von der Leyen’s words in Munich, a week out from the shock Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) result at the German federal election. The prospect of ¡No pasarán! one day becoming a stock phrase at the EU Commission does not seem far-fetched after all. Two months before her transition from Estonia’s premiership to the Commission’s foreign policy vice-presidency as part of von der Leyen’s second cabinet, Kaja Kallas doubled down on the case for more aerial defence systems to be donated to Ukraine, in an interview with Spain’s chief left-wing daily, El País. She urged EU leaders to see Russia’s offensive as part of a once-familiar existential threat to the continent’s territory and values. She spoke of a mistake being repeated, now, in reference to Europe’s failure to react to such premonitory forerunners of fascist aggression as… the Spanish Civil War.6

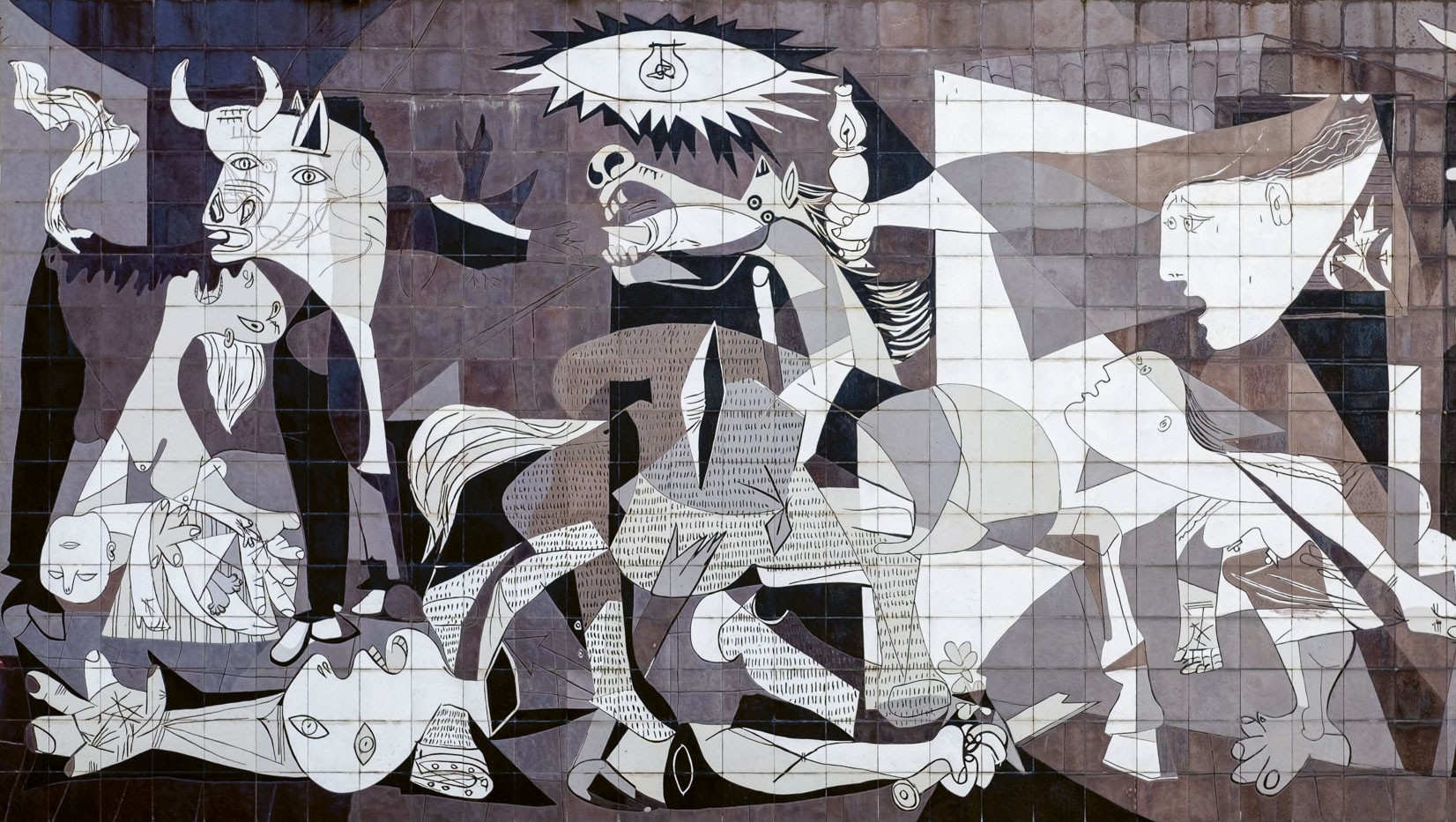

These left-radical wellsprings of today’s militant liberal discourse are shrewdly harnessed by President Zelenskyy himself. Speaking to Spain’s lower house via Zoom from the Mariinskyi Palace two months into the invasion,7 he pitched his war-torn nation as heirs to the Second Republic. ‘We live in April 2022, but it seems we are in April 1937, when the whole world suddenly awoke to the bombing of Guernica’,8 he said, alluding to the Basque town blitzed into rubble by the Condor Legion in a war crime later construed as a testing ground for the Second World War. Zelenskyy spoke midway through the 86-day-long siege of Ukraine’s own seaside town of Mariupol that would fall to Russia in late May. The contorted faces of Guernica’s civilian victims cry out into the vacuum of Picasso’s cubist masterpiece, but Zelenskyy that day was set on granting liberals the chance they had missed in 1936 to stop the fascist Armageddon. Buried in the congressional record amidst ghastly accounts of Russia’s advance, the daring parallel went largely unchallenged, perhaps unnoticed, in Spain. It was inaccurate and ineffectual—Zelenskyy’s next in-person visit to Spain in May 2024 carried no such allusion—but it nonetheless merits scrutiny.

‘Far from far-sighted, the mantra that Europe should re-learn forgotten lessons or resign itself to perish here becomes dangerously myopic’

On the one hand, Ukraine’s leader had already won over his audience. Except for an anti-NATO left fringe that views him as no less fascist than Putin and parallel hints of war fatigue on the populist right, Spaniards, to this day, favour some continued aid to Ukraine. The feckless defence underspending under socialist PM Pedro Sánchez was, if anything, more unpopular than Zelenskyy’s demands when he made them. Yet for the latter to invoke the fratricidal history of a potential aid donor—a committed one at that, Spain being so geographically removed from the frontline—was doubtless not without risk. Young Spaniards may be indifferent to the hoary lore of that war, but their elders are not. Had the quote been more widely covered, the appropriation of a civil drama before the very chamber born of reconciliation between ‘the two Spains’ in 1978, upon Franco’s death, may have been resented by virtually anyone for whom the war is, at most, one generation removed from living memory.

Then again, Zelenskyy knew the right feathers would go unruffled. The purse-strings he lobbied were held, he knew, by a Popular Front-like coalition led by Sánchez that revels in the very same sepia-toned, Manichean, 1930s Republican symbolism. The month before, when Spain’s first arms shipment to Ukraine was decreed, El País had stated in its editorial: ‘Today, the weapons to defend Ukraine are those that the Republic did not have 80 years ago.’9 NATO’s June summit this year would later expose Sánchez’s pro-Ukraine pandering to be mere rhetoric,10 while Zelenskyy’s references to Spain have since become more sparing. But the scavenging of Spain’s long-defunct civil quagmire for newfound global relevance now far transcends the two nations. In fact, the scavengers live mostly in neither country.

Another startling case, that of George Will, dramatizes what a catalyst Ukraine’s resistance has become for an otherwise niche species: anti-populist conservatives gradually pulled into the liberal fold. The never-Trump Pulitzer awardee and columnist wrote in September 2024: ‘If Putin succeeds, historians generations hence might designate Russia’s war against Ukraine—as they did, after World War II, the Spanish Civil War—the “great rehearsal”, a bloody prologue to a blood-soaked aftermath.’11 Francoist sympathies amongst the early Cold War-era US conservative movement, of which Will was a part,12 may seem remote, but Ukraine has proved a hefty accelerant to the author’s decades-long drift. By the 2020s, liberal recoil from national-populism had pushed Will to side, if only tacitly, with ongoing plans to topple the Valley of the Fallen, the Catholic reconciliatory memorial near Madrid, built at Franco’s behest in 1940, that came to house the strongman’s remains until they were exhumed amidst the Sánchez-led coalition’s ‘democratic memory’ law in late 2019. Likening the fractured memory of Spain’s war to America’s wrangling over Confederate statues, Will wrote in The Washington Post: ‘Spaniards might be embarking on a confrontation with their past akin to the one Americans are having about theirs, 155 years after Appomattox…They are in the difficult process of striking a delicate balance between necessary remembering and judicious forgetting…The Valley is a residue of Europe’s past that suggests what the continent’s future would have been if fascism had not been defeated in the previous century.’13

Will’s larger camp of repentant ex-conservatives—the Frums, Applebaums, and Kristols of the world—are entitled to view Ukraine’s war as a life-or-death contest for liberal internationalism writ large, even at the risk of eclipsing a narrower—and more popular—case for the country’s sovereign survival. But Will’s doomsday scenario of a Ukrainian defeat triggering a continental inferno, with echoes to the 1930s, is rooted in an entirely distorted reading of Spain’s past—so distorted that only the anti-fascist language of apocalyptic struggle befits his case. Will, and others on the Western right-of-centre, are now keen purveyors of that lexicon. Whereas liberals once tacked neutral when illiberal forces of right and left collided on Spanish soil in 1936–39, Will retrofits liberalism’s ordeals of the 2010s and 2020s into a national fratricide that will mark its centenary in a decade—with no appraisal of Spain’s likeliest future had the USSR-backed Popular Front won the day. Omens like his, likewise, never fail to omit the Republic’s Red Terror behind enemy lines against non-leftist civilians and churchgoers, accelerated by but predating the war’s outbreak.14 Will’s generation of anti-Soviet liberals and neocons has elsewhere been chided for inheriting an outdated, idealistic lens from the Cold War, but what side they fall on in each instance of their own Manichean, concocted binaries remains potentially perplexing.

The forgetting of Bolshevik-like Republican atrocities is all the odder in Europe, where even proximity is insufficient to compensate for the ideological preconceptions of pro-Ukraine revisionists of the Spanish war. Take Manuel Valls, the formerly socialist French prime minister and now minister for overseas territories in Emmanuel Macron’s cabinet after a quixotic 2018 bid for mayor of Barcelona on the strength of his dual citizenship. In 2016, Valls wrote the foreword to historian Gilbert Grellet’s Un été impardonnable,15 a history of the ‘unforgivable summer’ leading up to the outbreak of the Civil War. In a Spanish op-ed in March 2023, quoting from the monograph, he wrote: ‘In 1936, the democratic world fractured itself, forfeited to totalitarianism, and abandoned Spain to its luck. It is a warning for Europe not to commit the same mistakes.’16 Oddly for Valls—though elsewhere conventional wisdom—the USSR was the only foreign power to significantly meddle in Spain on the Republic’s behalf, meaning only its appraisal as a democratic regime would salvage the validity of his statement. Instead of castigating Europe’s liberal cowardice, per the erstwhile norm, Valls chooses to cast the democratic world of 1936 as divided. This lament for liberal-democratic disunity allows him to heighten the admonition to that world’s successors today, but it also subsumes the Soviets into that mantle—which, conversely, ties coherently into the conceptual liberal-red rapprochement that undergirds the mnemo-political process at hand.

More surprising still in the relational dissonance between 1936 and 2022 is how deep it runs in the imagination of died-in-the-wool liberals, a mental blur at which the French in particular seem to excel. François-Guillaume Lorrain, a historian and editor at the respectably bourgeois Le Point, wrote for that magazine the month after the Russia–Ukraine War broke out of it having an ‘aftertaste’ (arrière-goût) of Spain: ‘as for the ideological substance insufflated by a Putin hell-bent against a decadent and hostile West, it was similarly flagrant in 1936.’17 Meanwhile, in the pages of the august Revue des Deux Mondes, as part of an essay on Raymond Aron that overlooked the late French liberal philosopher’s neutral pessimism as the Spanish Civil War evolved,18 the Aronist exegete Nicolas Baverez wrote this year: ‘Europe finds itself on the frontlines of Ukraine’s war, which resembles in many ways the Spanish war that served as a testing ground for totalitarian regimes, and as a laboratory for the Second World War.’19

Dominique Moïsi of the Paris-based, centrist Institut Montaigne, for his part, weighed in similarly for Les Échos, two years after the invasion: ‘The war in Ukraine is one of those decisive moments that are often supplied by history, that call on us to respond—a final warning…before the fall into the abyss. It is, despite multiple and clear differences, our Spanish war. The lessons about the failure a century ago should make us redouble our support for Kyiv…At stake is not just democracy, but peace versus adventurism. As in 1939, we must put a stop to it before it’s too late.’20

Strikingly for a cast of eminent French liberals, the common root of these analogies is a familiar raccourci, a similar economy of nuance. The caveats prescribed by scholarly etiquette are here subordinate and overridden by a shortcutting presentism that bridges yawning gaps between 1936 and 2022, leaving a crass utilization of history overexposed. The method has found practitioners far and wide. For The National Interest in April last year, former US State Department official Richard M. Sanders sought to raise a historical mirror to the present, to which historians are naturally prey, but ended up typifying this rough-hewn approach:

‘A small country on Europe’s edge faces a ruthless attack…With the help of a major outside power, it defends itself with some success…Idealistic volunteers join the fight. However, the small nation’s patron eventually loses interest, and the flow of arms dries up. The country succumbs, its story cherished by those who believed in its cause. But over time, the price of walking away becomes clear as Europe enters a new era of conflict.’21

Though Sanders goes on to opine that ‘the story is not yet written’ and that ‘historical comparisons are never exact’, his sleight-of-hand is by now a familiar one: barely conjecturing the escalation that could be allegedly forestalled by more heftily aiding Ukraine, paired with the equally flimsy counterfactual of Franco’s defeat slowing down the Third Reich’s expansion. The overlapping year 1939 is thus turned into an epochal hinge—Spain slumbers into fascism while Europe careens into war, one and the same evitable drama—even as Allied neutrality in Spain is nowhere proven to have accelerated, by way of Franco’s victory, Nazi adventurism. These unwarranted assumptions eventually narrow Sanders’s case down to its lone, immediate bearing: belief that the values on the line in Ukraine make the war a ‘global’ one, and prescription against the West ‘liquidating its commitment’. Sanders warns, further, that Western retreat in Ukraine will be seized upon by Putin, who will draw ‘similar conclusions’ to those Hitler learnt, along his warpath, from liberal fecklessness—concluding in a note that fully detaches his case from any grounding in Spain’s experience whatsoever.22

When it does not dwell on moral crucibles, this premonitory casting of Ukraine as the last bulwark against a nightmarish replay of the 1930s retreats to the comparative study of warfare and its brute facts. Speculative analogies to belligerent intents and motives are often prefaced, as in Sanders’s case, by a mutandis-mutandis case for similarities between the two wars. These concern the balance of armed strength, bombardments and civilian death tolls, the testing of new technologies, international alliances, refugees and displaced families, the diplomatic aftermath—and, most of all, foreign volunteers. Forty thousand of those helped globalize attention to the Spanish Civil War by joining the International Brigades against Franco. A paragon of vindictive failure, 10,000 of them died in battles that mostly ended in defeat. In late 1938, the ruling Popular Front dissolved them in a last-ditch attempt to woo non-interventionist countries into sending troops. Early in the invasion of Ukraine, Giles Tremlett, a historian of the Brigades, expounded in The Guardian upon ¡No pasarán! and ‘the anti-fascist slogan’s new significance’: ‘Putin’s invasion made the phrase terrifyingly relevant, especially as volunteer fighters from across the world gather to defend Ukraine…Both Hitler and Mussolini sent troops to fight alongside the violent right-wing reactionaries led by Franco…Like Putin, they sought to demolish democracy across Europe.’ 23

As hailed by Tremlett, the Brigades long seemed a settled icon. Victims of liberal cowardice and neglect, they offered a measure of vindictive failure, of idealistic sacrifice in the face of fascist evil. Yet their legacy of premonition, long the object of communist hero-worship, is now being seamlessly repurposed in a new liberal script starring Ukraine’s Foreign Legion (UFL). These were still in embryo when Tremlett wrote, though he rushed to cast the International Brigades as their precursor, even as the UFL’s numbers, now two years on, remain incredibly hard to estimate—ranging anywhere from 2,000 to 20,000—and enlistment is at a standstill. Although also a volunteer force, the UFL differs from the Brigades in its far higher share of professional soldiers, yet analogies continue to proliferate. Colin Freeman, a British war correspondent, wrote for The Spectator in April about a loose group of American UFV volunteers lobbying the Trump administration for more aid to Ukraine. The Legion is ‘the biggest mobilization of its sort since the Spanish Civil War’, wrote Freeman, ‘when 2,800 Americans joined the Brigades against Franco’s fascists’. Cast over these UFV veterans is the same cloud of vindictive doom: ‘despite their best efforts to be war’s social influencers, they see their chances of victory dimming, just as their predecessors eventually lost to Franco.’24

These precedents are not always parsed with the same facile convenience. Elsewhere, they come prefaced by a recognition of evident differences, even as authors disagree on where the comparative overstretch may lie. Swiss historian Stéfanie Prezioso, a historian and MP with the left-wing grouping Ensemble à gauche, refutes parallels altogether. The author of ‘Tant pis si la lutte et cruelle: volontaires internationaux contre Franco’, she stood as a guardian of the Brigades’ memory against opportunistic analogies when interviewed by France’s BFMTV in March 2022. Citing the non-civil nature of Ukraine’s war, she suggested as a more fitting precursor the African American volunteers who enlisted to save Ethiopia from Italy’s fascist aggression in 1935.25

Oberlin College’s Sebastiaan Faber, for his part, was even more forthright about lacking parallels in The Conversation, even as he extolled the sacrifice they drew from: ‘As a scholar of the Civil War and its legacy, I can see why many would be tempted to read the Ukraine war through a Spanish lens…As in Spain, the war seems to reflect an unusual degree of moral clarity…a clear good and bad side…Tempting as it is, comparing the two obscures more than explains. In some instances, I see the analogy relying on distorted frames inherited from the Cold War; in others, it seems driven by blatant opportunism. The Brigades…have little in common with the combat veterans and Ukrainian nationalists signing up today, whose politics…are vague and may skew to the right or far right. While Russia’s invasion clearly violates Ukraine’s sovereignty, those defending it represent ideologies that cover the entire spectrum…’26

The displaced are another contested locus of comparison. In a Le Monde op-ed in March 2022, Rémi Serrano, a grandson of Spanish Republicans, sought to weave the experience of Ukrainian refugees into a shared, European narrative of displacement, claiming it recalled that of his family arriving to France: ‘We will honour those who died fighting for their country, we will together revisit the memories of the life we will have definitively lost, hoping that pain won’t blind us or crystallize in vengeance, but that we’ll be able to transcend it together in order to, one day, reconstruct.’27

Although in Ukraine’s disfavour, here again Faber deflates any resemblance—even as rising hostility towards refugees across host nations to the West risks rekindling it. Unlike Ukrainians, Spanish refugees ‘were not welcomed with open arms’, and indeed were at times put in concentration camps—15,000 of those interned in France were later deported to Nazi camps, where some 5,000 died—with most other countries simply closing their borders. The fate, meanwhile, of abducted children, where parallels have also been drawn, is asymmetrical for different reasons; the case of the so-called ‘lost children of Francoism’ removed from Republican parents was silenced at the time, but remains a far cry from the 20,000 Ukrainian children forcibly transferred and abducted into Russian families during the ongoing war.28

Granted, with Europe again facing the prospect of war, discerning precedents to our confounding predicament may come as a natural reflex, if at times conditioned by ideology. Yet in the case of Ukraine and Spain, it also produces circumstantial parallels that obscure the unbridgeable gap between the very natures of the two conflicts, conflating the ideological antagonisms of the 1930s at their most nationally internecine with a globalized, technological war for territory. Far from far-sighted, the mantra that Europe should re-learn forgotten lessons or resign itself to perish here becomes dangerously myopic. Either transnational liberalism, not its narrower survival, is that for which Ukraine wages war—akin to how Spanish Republicans fought a last-ditch attempt for anti-fascist humankind—or Russia’s mirror framing of a defensive war for traditional values is bogus. Western liberals cannot have both. For Faber, ‘invoking Spain to frame the invasion as a clash between fascism and anti-fascism plays into the Kremlin’s narrative, which seeks to portray the “special military operation” as an effort to “denazify” its neighbour’.29 Equating the two wars, furthermore, also means hybridizing some of their most contrasting features. The posterity of one contest, Spain’s, deepens the ideological substance at stake, leaving it ripe for ex-post, opportunistic manipulation. It also implies that armed combat itself is over. This leaves Ukraine’s ongoing quagmire, within such comparative frames, as having at least some civil element to it. Instead of a defensive war against foreign imperialistic aggression, the fabricated echoes of Spain turn it into the intra-Slavic dispute of Putinist fantasy.

This comparison trap need not be fatal. Without forfeiting retrospection, the dilemma is deftly avoided by one of Ukraine’s most effective cheerleaders. Finland’s President, Alexander Stubb, prefers to locate the lessons for Ukraine in his own nation’s victory against the USSR in 1944,30 however problematic those may be for their own reasons.31

These premonitory parallels, ultimately, should also be assessed in their dynamic breadth, by what is sought with them—the sense of doom, of vindictive failure, and of vindication being at times more important than victory. Woven into the routine calls for greater aid to Ukraine that have become a hallmark of Europe’s news cycle is a growing space for day-after scenarios—to be averted, surely, but also to be prepared for. While the Second Republic’s abandonment was a matter of calculated choice, Ukraine is arguably already one of the most externally backed belligerent forces in the history of modern warfare. It is, furthermore, the testing ground for an expansive array of new technologies, as indeed was Spain in its own time under the playful thumb of the Axis powers. Except that the deadlier technologies are now being tried on Ukraine’s side, and the West, fully invested in their use against Russia—as if the lessons from Spain were not under- but over-learnt—has less of a choice to abandon the escalatory ratchet.

These late-hour evocations would be harmful enough as foreign appropriation, as outside efforts to fan the smouldering embers of a national tragedy long defunct in its home base. Were they so, their affront to Spain would be collateral at best to the blight on historical inquiry from the distorted analogies themselves. But the appropriation ripples politically in Spain too, where the ruling left could not have asked for a better outside assist than a whitewashed Popular Front hoisted from the dead and into the respectable liberal fold. Aided by the vogueish lament for the Republic as somehow premonitory of liberalism’s travails, the Sánchez-led coalition’s slate of Orwellian legislation is now more easily viewed as a ‘reckoning’ with our internecine past, even as it shatters the settled amnesia that reconciled the nation upon Franco’s death in 1978. Whether Spaniards welcome these framings or not, they are unwittingly ceding their stock of trauma as rousing symbols for a foreign war at Europe’s far end. Sánchez—though far to the left of his liberal European elders—is all too happy to lease the national wounds he is bent on reopening, this time to reinfuse liberalism’s spent vision for another world-ideological contest. The fratricidal animus he has whipped up since rising to office in 2019 is not only not a liability—it is an asset.

Broader lessons about the ideological direction of the West are not for Spain alone to parse. They also far transcend Ukraine’s current stalemate. The besieged liberal West of the 1930s was once chided by Marxists for abandoning Spain to four decades of repressive obscurantism. Today, the inheritors of both currents join hands in taking retroactive sides on a war that most Spaniards would rather leave unstirred, with apprehensive liberals listening to the vindictive failure of far-leftists. It is hard not to see a momentous rapprochement of a kind the twentieth century did not presage. Meanwhile, the psyches of other traumatized nations could be similarly scavenged in search of stirring legends, the depths of their unconscious dredged.

NOTES

1 Charlotte Fereday, ‘No Pasarán: How Pussy Riot made a slogan their own’, Litro Magazine (2 January 2014), www.litromagazine.com/arts-and-culture/no-pasaran-how-pussy-riot-made-a-slogan-their-own/.

2 Luis de Vega, ‘El “¡No pasarán!” llega a las barricadas de Kiev’, El País (8 March 2022), https://elpais.com/internacional/2022-03-08/el-no-pasaran-llega-a-las-barricadas-de-kiev.html.

3 ‘Ucrania: el no pasarán del movimiento Euromaidán’, Euronews Video (2024), www.youtube.com/watch?v=rcPRMpkGKgw.

4 ‘Ucrania’, Partido Comunista de España (Marxista– Leninista) (n. d.), https://pceml.info/tag/ucrania/, accessed 15 November 2025.

5 ‘Alberto Alemanno’, LinkedIn, www.linkedin.com/posts/alemanno_the-eu-not-russia-not-china-but-the-eu-activity-7296434984192471042-Ud2j/, accessed 20 November 2025.

6 Mária Sahuquillo, ‘Estonian Prime Minister: “It’s a question of when they will start the next war”’, El País English (18 April 2024), https://english.elpais.com/international/2024-04-18/estonian-prime-minister-its-a-question-of-when-they-will-start-the-next-war.html.

7 ‘Discurso completo de Zelenski en el Congreso de los Diputados: “Es 2022, pero parece abril de 1937”’, El Confidencial (5 April 2022), www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZetWgyzxAN8.

8 ‘Consulte el discurso íntegro de Volodimir Zelenski ante el Congreso’, El Mundo (5 April 2022), www.elmundo.es/espana/2022/04/05/624c9238e4d4d801098b4574.html.

9 ‘La legitimidad de las armas’, El País (3 March 2022), https://elpais.com/opinion/2022-03-03/la-legitimidad-de-las-armas.html.

10 Carlos E. Cué, Silvia Ayuso, and Macarena Vidal Liy, ‘“Spain is a problem”: Trump Lashes out over NATO Contributions’, El País English (25 June 2025), https://english.elpais.com/international/2025-06-25/spain-is-a-problem-trump-lashes-out-over-nato-contributions.html.

11 George F. Will, ‘As Putin’s Military Barbarism Continues, U.S. Credibility Is at Stake’, The Washington Post (25 September 2024), www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2024/09/25/putin-russia-ukraine-war/.

12 Jacob Heilbrunn, ‘He Was Dismissed as a Conservative Kook. Now the Supreme Court Is Embracing His Blueprint’, Politico (7 July 2022), www.politico.com/news/magazine/2022/07/07/leo-brent-bozell-abortion-game-00044246.

13 George Will, ‘There Is Much to Remember about Spain’s History. And to forget’, The Washington Post (20 January 2020), www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/spain-faces-an-ongoing-grapple-with-the-politics-of-memory/2020/01/16/c8ac9c6e-3892-11ea-9541-9107303481a4_story.html.

14 Julius Ruiz, The ‘Red Terror’ and the Spanish Civil War: Revolutionary Violence in Madrid (Cambridge University Press, 2015), 1–15.

15 Manuel Valls, ‘Preface’, in Gilbert Grellet, Un été impardonnable (An Unforgiveable Summer) (Éditions Albin Michel, 2016).

16 Manuel Valls, ‘La Guerra Civil y la guerra de Ucrania: lecciones del pasado para el presente’, El Español (5 March 2023), www.elespanol.com/opinion/tribunas/20230305/guerra-civil-guerra-ucrania-lecciones-pasado-presente/746045391_12.html.

17 François-Guillaume Lorrain, ‘En Ukraine, un arrière-goût de guerre d’Espagne’ (In Ukraine, an Aftertaste of the War in Spain), Le Point (20 March 2022), www.lepoint.fr/monde/en-ukraine-un-arriere-gout-de-guerre-d-espagne-20-03-2022-2468929_24.php.

18 Raymond Aron, Mémoires: Raymond Aron (Éditions Robert Laffont, 2025).

19 Nicholas Baverez, ‘Repenser l’Europe au XXIe siècle avec Raymond Aron’ (Rethinking the Europe of the Twenty-First Century with Raymond Aron), Revue des Deux Mondes (24 February 2025), www.revuedesdeuxmondes.fr/repenser-leurope-au-xxie-siecle-avec-raymond-aron/.

20 Dominique Moïsi, ‘L’Ukraine, notre guerre d’Espagne’ (Ukraine: Our War in Spain), Les Échos (7 January 2024), www.lesechos.fr/idees-debats/editos-analyses/lukraine-notre-guerre-despagne-2044735.

21 Richard Sanders, ‘Spain 1939, Ukraine 2024?’, The National Interest (3 April 2024), https://nationalinterest.org/feature/spain-1939-ukraine-2024-210172.

22 Sanders, ‘Spain 1939, Ukraine 2024?’

23 Giles Tremlett, ‘No pasarán: Anti-Fascist Slogan Takes on New Significance in Ukraine Crisis’, The Guardian (12 March 2022), www.theguardian.com/world/2022/mar/12/no-pasaran-anti-fascist-ukraine-spanish-civil-war.

24 Colin Freeman, ‘Ukraine’s Foreign Legion Was Doomed from the Start’, The Spectator (4 September 2025), www.spectator.co.uk/article/ukraines-foreign-legion-was-doomed-from-the-start/.

25 Robin Verner, ‘Avec les volontaires étrangers en Ukraine, le souvenir des Brigades internationales de la guerre d’Espagne’, BFMTV (8 March 2022), www.bfmtv.com/international/derriere-les-volontaires-etrangers-en-ukraine-le-souvenir-des-brigades-internationales-de-la-guerre-d-espagne_AN-202203080497.html.

26 Sebastiaan Faber, ‘Ukraine’s Foreign Fighters Have Little in Common with Those Who Signed Up to Fight in the Spanish Civil War’, The Conversation (17 March 2022), https://theconversation.com/ukraines-foreign-fighters-have-little-in-common-with-those-who-signed-up-to-fight-in-the-spanish-civil-war-178976.

27 ‘“Paroles de lecteurs” – De l’Espagne à l’Ukraine, une même histoire de réfugiés’ (‘Readers’ Words’: From Spain to Ukraine, a Similar Story of Refugees), Le Monde (31 March 2022), www.lemonde.fr/blog-mediateur/article/2022/03/31/paroles-de-lecteurs-de-l-espagne-a-l-ukraine-une-meme-histoire-de-refugies_6119912_5334984.html.

28 Faber, ‘Ukraine’s Foreign Fighters Have Little in Common with Those Who Signed Up to Fight in the Spanish Civil War’.

29 Faber, ‘Ukraine’s Foreign Fighters Have Little in Common with Those Who Signed Up to Fight in the Spanish Civil War’.

30 ‘What Finland Could Teach Ukraine About War and Peace’, The Economist (1 September 2025), www.economist.com/europe/2025/09/01/what-finland-could-teach-ukraine-about-war-and-peace.

31 Bo Petersson, ‘Why Ukraine Should Avoid Copying Finland’s 1944 Path to Peace with Moscow’, The Conversation (23 September 2025), https://mau.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A2008574&dswid=9985.

Related articles: