‘Crime’—observed the French sociologist Emile Durkheim at the end of the 19th century—‘brings together upright consciences and concentrates them.’ ‘They stop each other on the street,’ he continued, ‘they seek to come together to talk of the event and to wax indignant in common.’ The more severe the crime, he theorized, the more passionate the ‘public temper’ would be against it, serving to reinforce the elementary distinction between right and wrong.

Well, the bit about passions still holds: crime certainly continues to excite those. But the idea that it draws people closer together and serves to reaffirm a moral consensus is a relic of a past long gone. If Durkheim were writing today, he might put it like this: crime brings together unscrupulous consciences and concentrates them. They harangue each other on the internet, they block interlocutors they disagree with and return to their echo chambers where they wax indignant about their foes.

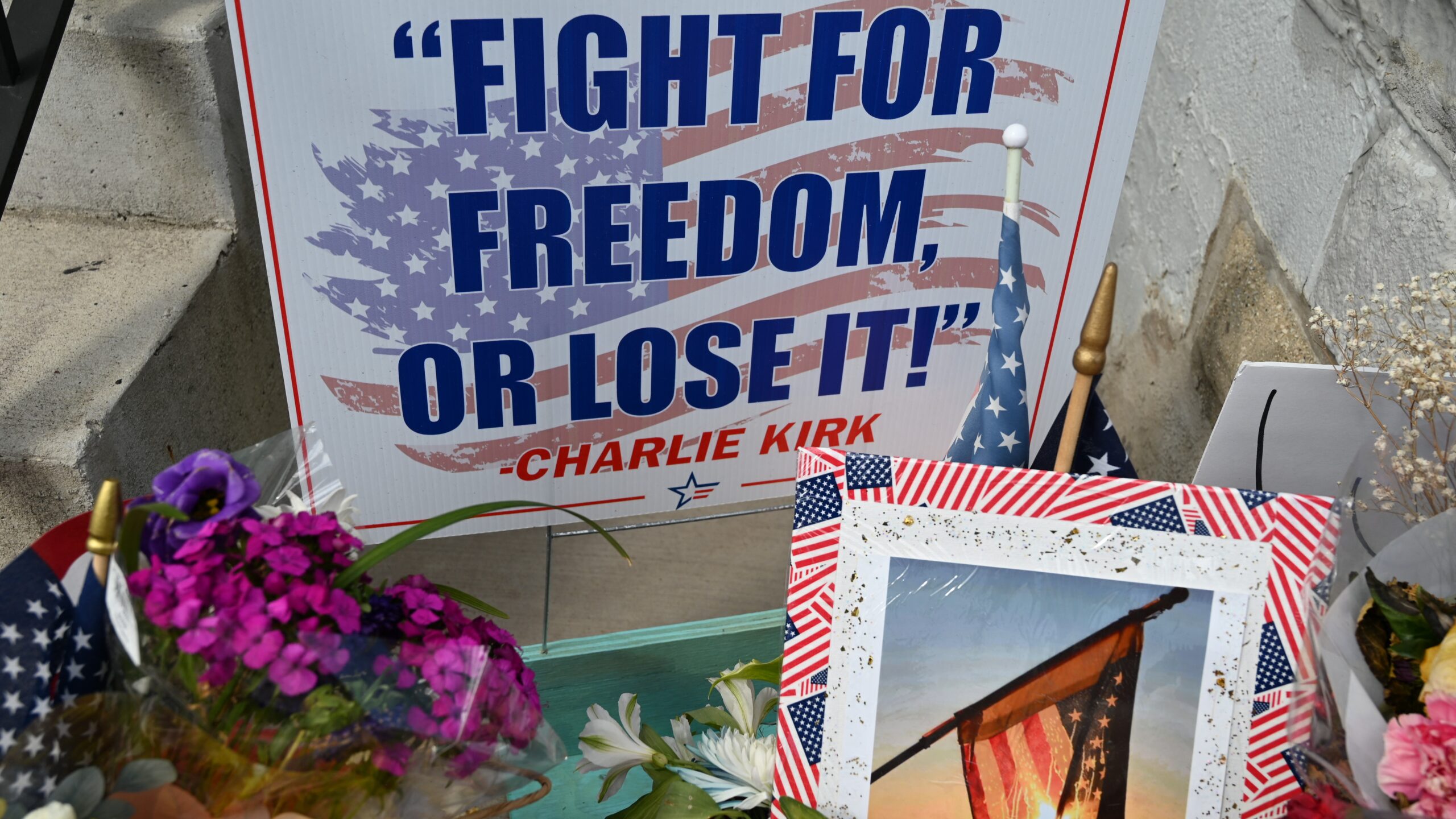

Nothing more graphically illustrates this regressive unravelling than the inferno of online reaction to the assassination of Charlie Kirk, where vast sub-sections of the American population came together not to collectively condemn Kirk’s murder but to quarrel over its meaning and demonize each other.

Indeed, one could be forgiven for thinking that most Americans, to paraphrase Rod Dreher, are living in an entirely different epistemological universe from one another. ‘They sincerely believe MAGA shot Charlie [Kirk] & Jimmy Kimmel is the real martyr,’ Dreher said on X, referring to US liberals who objected to the suspension (now revoked) of Kimmel from his late-night TV show after he falsely suggested that Kirk’s killer was MAGA-affiliated. He wasn’t—although how Tyler Robinson came to develop a murderous loathing of Kirk and act on it remains unclear.

Kimmel was scarcely a lone voice in thinking that Kirk’s murderer had come from the right. Indeed, there was a whole contingent of people on the left-leaning Bluesky platform who expressed their staunch belief that he was a ‘Groyper’—a far-right fanboy of the white supremacist Nick Fuentes—and that his motive for killing Kirk was that he wasn’t right-wing enough. This, as Graeme Wood recently observed, was chiefly because they wanted to believe it. ‘It hurts to admit that a movement you like has produced a bad person,’ Wood wrote, ‘and it hurts even more to admit that bitter truth to a gloating member of a movement you hate.’

‘It hurts to admit that a movement you like has produced a bad person’

Others still, from all quarters of the political spectrum, believed that Kirk was murdered by the Israeli state because, they asserted, he was about to break with Zionism. In recent days, I have seen this theory advanced by people as far apart politically as incels and trans women. Just like those advancing the ‘groyper’ theory, these conspiracy theorists want to believe that Israel organized Kirk’s murder, since it advances their antisemitic view that Jews are behind all the evil in the world.

Kirk’s assassination also shines a stark light on the different moral universes that some of us would appear to inhabit, too. While many, including mainstream democrats and liberals, condemned Kirk’s murder and expressed revulsion at the terrible injustice of it, others ostentatiously celebrated it or sought to imply that Kirk deserved his fate. For exhaustive documentation of the latter, you can visit this link.

No doubt, to some degree, we have always lived in separate epistemological and moral universes. When, for example, al Qaeda attacked America on 9/11, many cranks from both the right and left speculated that it was an ‘inside job’, while a toxic coalition of Christian fundamentalists and left-wing anti-imperialists blamed America for the attack due to its spiritual corruption and crimes of empire, respectively.

Yet today it feels like we’re at an inflection point, because the lines that divide us have never been sharper. The internet has fuelled this, since by drawing us closer together it has also magnified our differences. But the driving dynamic behind our current increasingly polarized world is the insatiable rise of a public culture engorged on atrocity in the age of the smart phone. I now get to know what my local car dealer or a pizza delivery guy in a city I’ve never heard of thinks about Charlie Kirk and Israel and much else. This, in turn, is thanks to the erosion of the private-public distinction, which social media has intensified.

Even before the rise of social media, that distinction was fraying, largely because of deep changes in the contemporary self and the dominance of a therapy culture that de-stigmatized the sharing of people’s inner-most thoughts. But therapy culture was never about telling other people how sociopathic your were; it was about revealing your wounds and attracting sympathetic attention.

Therapy culture has not gone away, but it now coexists with a super-charged ‘perpetrator culture’ that voyeuristically fixates on the wound-makers. Perpetrator culture isn’t new: for many decades, fandoms around serial killers, terrorists, hitmen, school shooters, suicide bombers, drug-lords and gangsters have existed, but they were not at the forefront of social and political life. Indeed, they were part of a subterranean world and one that, for its inhabitants, was all the more alluring for that. Before the internet, you would need specialist knowledge to find these places of minority interest. Today, these places find you.

‘Therapy culture has not gone away, but it now coexists with a super-charged “perpetrator culture”’

Social media platforms now act as a conduit for atrocity video-footage, delivering it to your timeline whether you like it or not. The footage served up, which very many duly click on because it takes the form of ‘breaking news’ or arouses our morbid curiosity, is often harrowing, showing the most graphic images of real-world violence—and in the case of Kirk’s assassination, the gory spectacle of his assassin’s bullet ripping into his neck.

This footage, when politically inflammatory, is apt to provoke a firehose of incendiary commentary, which in turn generates yet another firehose of incendiary commentary, which draws in others who may not otherwise have heard about or seen the original atrocity footage, restarting the cycle of outrage. It is a deeply unhealthy dynamic, and one that is incentivized by an attention economy that rewards those who share extreme content or say extreme things about that content.

As a result, it becomes difficult for us to collectively process and make sense of terrible atrocities, because within moments of them happening—or indeed as they are happening in real time—we are emotionally overwhelmed by the spectacle of their occurrence. This is further compounded by the immediacy of the clamour and confusion that the atrocity footage itself generates.

‘There is a very real risk that we come to believe the entire planet has lost its moral bearings’

The other problem associated with this dynamic is a warping of the collective mind, where we not only risk becoming ever more desensitized to violence, but convinced that there is far more of it than there actually is. At the same time, because we are over-exposed to so much of the hectoring and ‘shitposting’ of strangers responding to atrocities, there is a very real risk that we come to believe the entire planet has lost its moral bearings. This then makes us even more distrustful and less open to other people we don’t know.

It isn’t clear what can be done to reverse this dynamic of polarization and derangement. But we are not powerless to resist its grip and we could, if we choose, exercise more decorum in how we respond to the deaths of other people. And if we can’t screen out the most deranged voices online, we can at least try to resist their provocations.

Related articles: