The National Strategic Research Institute (NSKI) held its 7th interdisciplinary conference on the social and economic situation of Hungarians in the Carpathian Basin on 21–22 November in Székelyudvarhely (Odorheiu Secuiesc, Romania). Since last year, a section on ‘Hungarians Worldwide and the Hungarian Diaspora’ has also been included in the conference program. This section was led by Dr. habil. Ákos Jarjabka, associate professor at the University of Pécs (PTE), head of the PTE Diaspora Project Network (DPH) and the Hungarians Worldwide Network Program Office (VMNP), and Dr. Dániel Gazsó, lecturer, senior research fellow at the Ludovika University of Public Service (NKE) and research officer responsible for diaspora studies at the Research Institute for Hungarian Communities Abroad (NPKI).

In the era of modern migration, the situation of individuals and communities living beyond a country’s borders has growing importance from both national strategy and national policy perspectives. It is considered unique even in an international context that the totality of the Hungarian nation consists of three distinct components: those living within Hungary’s present-day borders (i.e. Hungarians living in the ‘motherland’); the minority Hungarians living as autochthonous communities in blocks or in dispersed form across the Carpathian Basin, i.e., on the territory of historic Hungary (i.e. ‘Hungarians beyond the border’); and the Hungarian diaspora communities scattered around the world as a result of several waves of immigration in the past centuries (i.e. ‘Hungarians living in the diaspora’).

The section leaders selected presentations for the ‘Hungarians Worldwide and the Hungarian Diaspora’ section that explore the history of Hungarians dispersed across the globe: the characteristics of past and present migration waves; the causes and effects of immigration on existing communities; the development and institutionalization of the Hungarian diaspora; the (re)organization of Hungarian communities, their interconnections and their network-building efforts. All this is presented from a social-science perspective, using both macro- and micro-level approaches, and highlighting various best practices—even illustrating individual Hungarian life stories and destinies—focusing on the experience of Hungarian and multiple identities, and exploring the possibilities of maintaining the Hungarian language, culture, folk traditions, and religious life. Diaspora policy practices (such as scholarship programs), their reception, the development of connections with the motherland, and opportunities for future improvement were also within scope for this section.

Eszter Rozs, project manager at the PTE VMNP, gave a presentation titled ‘Diaspora Identity and Citizenship: Cultural Self-Identity and Legal Attachment of the Hungarian Community in the United States’. Her doctoral research aims to survey, through online questionnaires and structured in-depth interviews, the strength of dual identity among Hungarians living in Florida, their willingness to acquire Hungarian citizenship, their intention to return to Hungary and the limitations and motivations associated with the above, as well as the relationship between certain background characteristics (such as age, language proficiency, family ties, economic status) and such willingness and intentions.

The speaker noted that, according to U.S. Census Bureau data (2020), 1.36 million people identify as having Hungarian origin (in part or in full), while the World Population Review (2025) estimates the same category, including 1.26 million individuals. The U.S. states with the largest Hungarian populations are: Ohio (158,300), New York (147,347), Pennsylvania (108,323), California (99,572), Florida (94,124), New Jersey (84,082), and Michigan (78,222).

‘The goal is for “being Hungarian” not to become merely a memory, but a living experience for future generations’

Members of Hungarian communities in the U.S. maintain their cultural ties in many ways—through language use, participation in church and civil organizations, and organizing community events. According to Rozs, these activities fall into five categories: mother-tongue communities and identity preservation (such as community houses and clubs; scout troops; weekend Hungarian schools; church communities; language camps, summer universities, Hungarian Language Days; Hungarian-language newspapers, radios, online portals; business networks); tradition preservation (including scouting; cultural events and holidays; folk dance and folk music; choirs, theater groups); community programs (e.g. Hungarian Days, festivals, exhibitions; online communities: Facebook groups, podcasts, online language classes; ‘Kapocs’ youth games; Shoot4Earth); cultural connections with the motherland (i.e. cooperation with Hungarian state programs; hosting scholarship recipients and organizing joint programs; participation in the Hungarian cultural diplomacy and national policy network); and religious practice (for example, masses, church fairs, charitable activities, community dinners).

She also presented the factors of generational transmission, which in the diaspora means not only the preservation of language or traditions, but the transfer of emotional, cultural, and communal heritage as well. The goal is for ‘being Hungarian’ not to become merely a memory, but a living experience for future generations. The elements of generational transmission include: passing on identity, language, culture, traditions, and values (which, besides language, includes community rituals); weekend Hungarian schools and youth programs (which consciously build on dual identity); digital and global connectivity (YouTube channels, social media, online Hungarian classes, podcasts); and intentional identity-building (many second- or later-generation young adults re-discover their Hungarian identity). Rozs emphasized the key role of teachers and volunteers— as ‘bridges’ of culture between generations—and the importance of participation in community and church life (Hungarian churches, clubs, and scout troops are typically multigenerational). Thus, generational transmission is not only a family process, but also a life-path-level reconnection.

Regarding Hungarian diaspora programs, she noted that they are not only support systems but strategic tools for building the global Hungarian national community. Their goal is for Hungarians—wherever they live—to preserve their identity, stay connected to the motherland, and participate in shaping the future of the Hungarian nation. In addition to strengthening national cohesion, these programs aim to preserve Hungarian identity, language, and culture; to involve younger generations; to maintain connections and networks with diaspora organizations; to strengthen ties related to returning to Hungary and citizenship; and to improve Hungary’s international image.

Finally, Rozs explained that empirical data is limited regarding how many people eligible for simplified naturalization actually make use of the opportunity to acquire citizenship based on ancestry. Her research also aims to assess whether language proficiency requirements, obtaining ancestral documents, or administrative demands hinder eligible individuals from actually acquiring citizenship.

Edit Dukai, PhD student at the PTE Doctoral School of Earth Sciences, presented on the life paths of Hungarian students from Romania, Slovakia, Serbia, and Ukraine who completed undergraduate or master’s studies at Hungarian higher education institutions. Her presentation was titled ‘I Came, I Saw, I Graduated! Should I Stay or Should I Go?’.

Her research seeks to understand what obtaining a Hungarian diploma means for those hundreds of young people from Hungarian communities beyond the border who graduate from Hungarian universities each year and enter the labor market. Using the Graduate Career Tracking System (DPR), the study aims to analyze Hungarian students born and raised in Romania, Slovakia, Serbia, and Ukraine—countries where nearly two-thirds of the Hungarian minority lives, two of these countries being European Union members and two are not—who completed undergraduate and/or master’s studies in Hungary between 2007 and 2017, identifying their post-graduation destination country and factors influencing their decisions. These factors are: socio-demographic background variables (country, age, gender, family educational background) and variables shaped during their studies (family status, field of study, study program, year of graduation, financing, and professional practice).

The speaker explained that the three strongest barriers to returning home are linguistic disadvantages, lack of a personal network, and the value of a Hungarian (therefore European Union) diploma. According to her research, one of the most important influencing factors is the place where the student starts a family. While degrees in the humanities and agriculture decrease the likelihood of staying in Hungary, degrees in natural sciences, medicine, and health sciences increase it slightly. Non-full-time study significantly decreases, while later graduation slightly decreases the likelihood of staying in Hungary; self-financed students are somewhat more likely to stay; and those with professional practice are more likely to return home upon finishing studies. In summary, the decision of those remaining in Hungary was shaped more strongly by experiences during their studies than by their background factors.

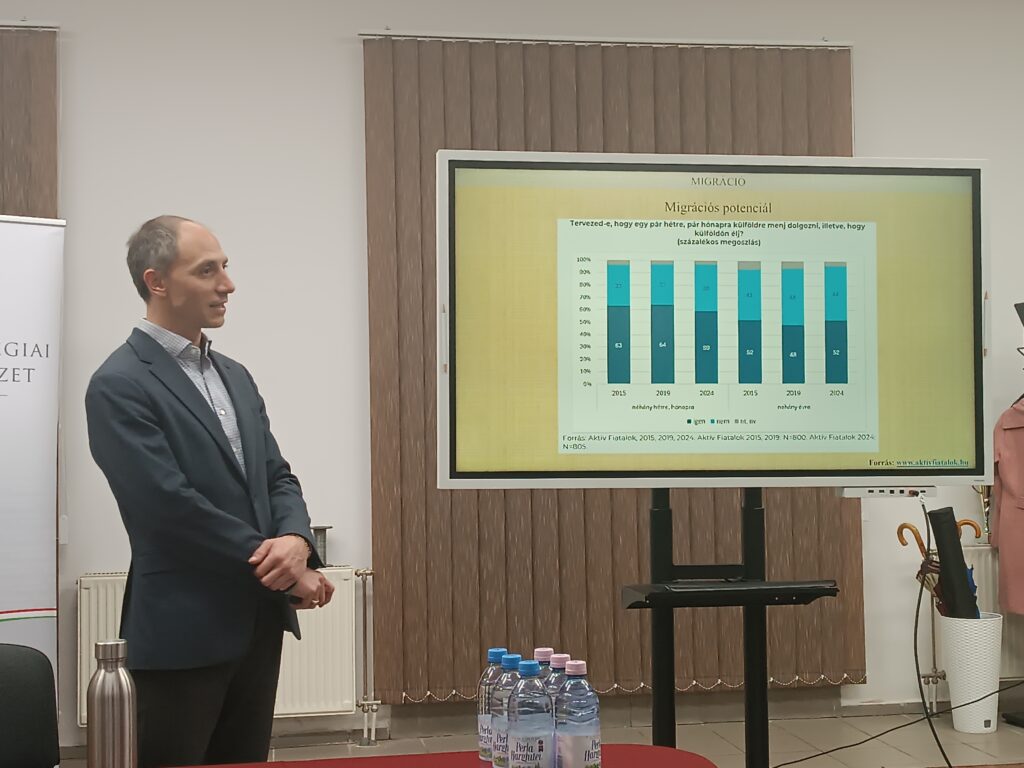

Dr. Dániel Gazsó, lecturer, senior research fellow at the NKE, and research officer at the NPKI, presented ‘Contemporary Hungarian Emigration’. His aim was to describe migration processes affecting Hungarian society today, with special attention to factors driving emigration from the Carpathian Basin to Western Europe. As he emphasized, emigration indicators showed extreme values and radical changes over the past decade. Due to the emigration wave often referred to as the ‘exodus of youth’, the number of Hungarian citizens who moved abroad exceeded 85,000 annually by the mid-2010s according to Western European mirror statistics, while domestic statistics reported only 20–35,000 Hungarian immigrants annually in the same period. The pace of emigration later slowed, and then rose again after the COVID pandemic. According to the data presented, the number of Hungarian citizens living in EEA countries and the UK was 89,713 in 2014 and 545,698 in 2023; the largest destination countries were Germany (35.5 per cent), the UK (21.6 per cent), Austria (18.3 per cent), Switzerland (5.1 per cent), and the Netherlands (3.8 per cent).

At the same time, more and more Hungarian-born citizens began returning home, their number—with the temporary stagnation during the pandemic—increasing from 15,000 in 2015 to nearly 30,000 in 2024. Cross-border commuting also became more common: according to the 2022 census, 117,000 people reported working abroad, 53 per cent of them in Austria and 21 per cent in Germany. Based on the emigration plans of young adults, the intention for short-term (weeks or months) and medium-term (a few years) work abroad decreased slightly or stagnated between 2015 and 2024. However, the number of young Hungarians planning to live abroad increased: while 37 per cent intended to do so in 2015 (53 per cent no, 10 per cent unsure), by 2024 the proportion rose to 45 per cent (49 per cent no, 6 per cent unsure).

It was also noted that emigration has become the primary factor in the population decline—as well as the spread of dispersion and ethnic loss of territory—among Hungarian communities in neighboring countries, especially in Transcarpathia, Transylvania, and Vojvodina. Summarizing the challenges of migration and diaspora studies, and related policymaking, he highlighted that the exact number of diaspora Hungarians is unknown; and regarding the diaspora, key issues include how to reach and involve younger generations in community life, how to encourage newly immigrated individuals to return; how to increase the effectiveness of diaspora organizations and what reintegration strategies could make ‘remigration’ policy more effective.

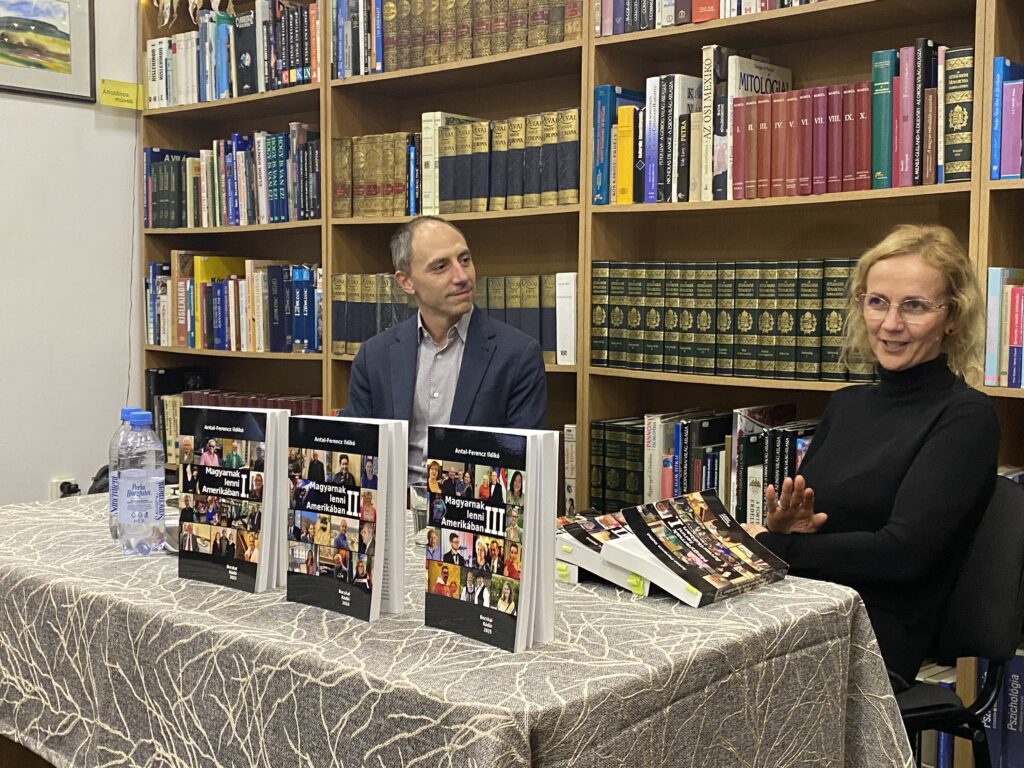

Freelance journalist Ildikó Antal-Ferencz, in her presentation titled ‘Being a Hungarian from Transylvania in America’, summarized the main experiences and lessons from her five interview volumes published by the Bocskai Radio in Cleveland (Magyarnak lenni Amerikában I–III.; Being Hungarian in America I–II.). The Hungarian-language books were also presented in the evening before the conference at the Székelyudvarhely Town Library.

At that event Dániel Gazsó interviewed the author about her childhood as an ethnic Hungarian living ‘beyond the border’ in Sepsiszentgyörgy (Sfântu Gheorghe, Romania), her family life following her university years in Hungary, her career first as an economist and later as a journalist, and finally about the past three years she spent in the U.S. While there, she actively participated in the Hungarian community life in the U.S. both as a private individual (mother of three scouts) and as a journalist, writing more than 200 articles in two languages about Hungarians living in North America—mostly on a voluntary basis. She also supported the Hungarian diaspora communities in many other ways.

Her books include more than 100 in-depth interviews conducted in nearly 20 U.S. states and in Canada, featuring Hungarians of varying ages, professions, immigration backgrounds, and geographic origins. These conversations present how Hungarians experience and transmit their identity—language, culture, traditions—in everyday life, both within the family and within Hungarian weekend schools, scout groups, church communities, folk-dance ensembles, and other civil organizations. Based on the volumes, the presentation evaluated the challenges faced by Hungarian communities in North America and their strategies for preserving identity and navigating life in the diaspora.

Approximately 20 per cent of her relevant interviewees are of Transylvanian origin, the overwhelming majority of whom are first-generation immigrants; some political refugees from before the regime change in Hungary and Romania, but mostly economic immigrants who arrived in North America after 1990. Through their disproportionately strong volunteer contributions—many claimed that without them certain communities wouldn’t even exist (for example, the vast majority of Hungarian Reformed pastors in North America are also from Transylvania; and both the author and the publisher of the interview volumes are of Transylvanian origin)—the patterns of maintaining Transylvanian Hungarian identity abroad also became visible (for example, Transylvanian-born individuals tend to seek each other’s company; if a community leader is from Transylvania, more Transylvanians tend to join that community; therefore, in some places they form local ‘pockets’ within the broader community (e.g., in Chicago, Il; Detroit, MI; or Wisconsin Dells, WI).

The author also revealed that her original intention was simply to get to know the daily joys and sorrows of these dedicated individuals and their communities in the North American diaspora, particularly regarding the preservation and transmission of Hungarian language, culture, and traditions—and then share these insights with readers in the Carpathian Basin.

However, based on feedback, her extensive and intensive work (which included more than 100 in-depth interviews, nearly 100 other reports, over 50 book launches, at least 10 radio interviews on diaspora-level events, and the organization of an online PTE DHK online conference), along with her experiences as a mother of three, yielded many additional outcomes: deeper mutual understanding; increased knowledge about various local/state communities and organizations; broader awareness of best practices and scholarship opportunities; and inquiries from libraries and researchers

Related articles: