The following is a translation of an article written by Emese Hulej, originally published in Magyar Krónika.

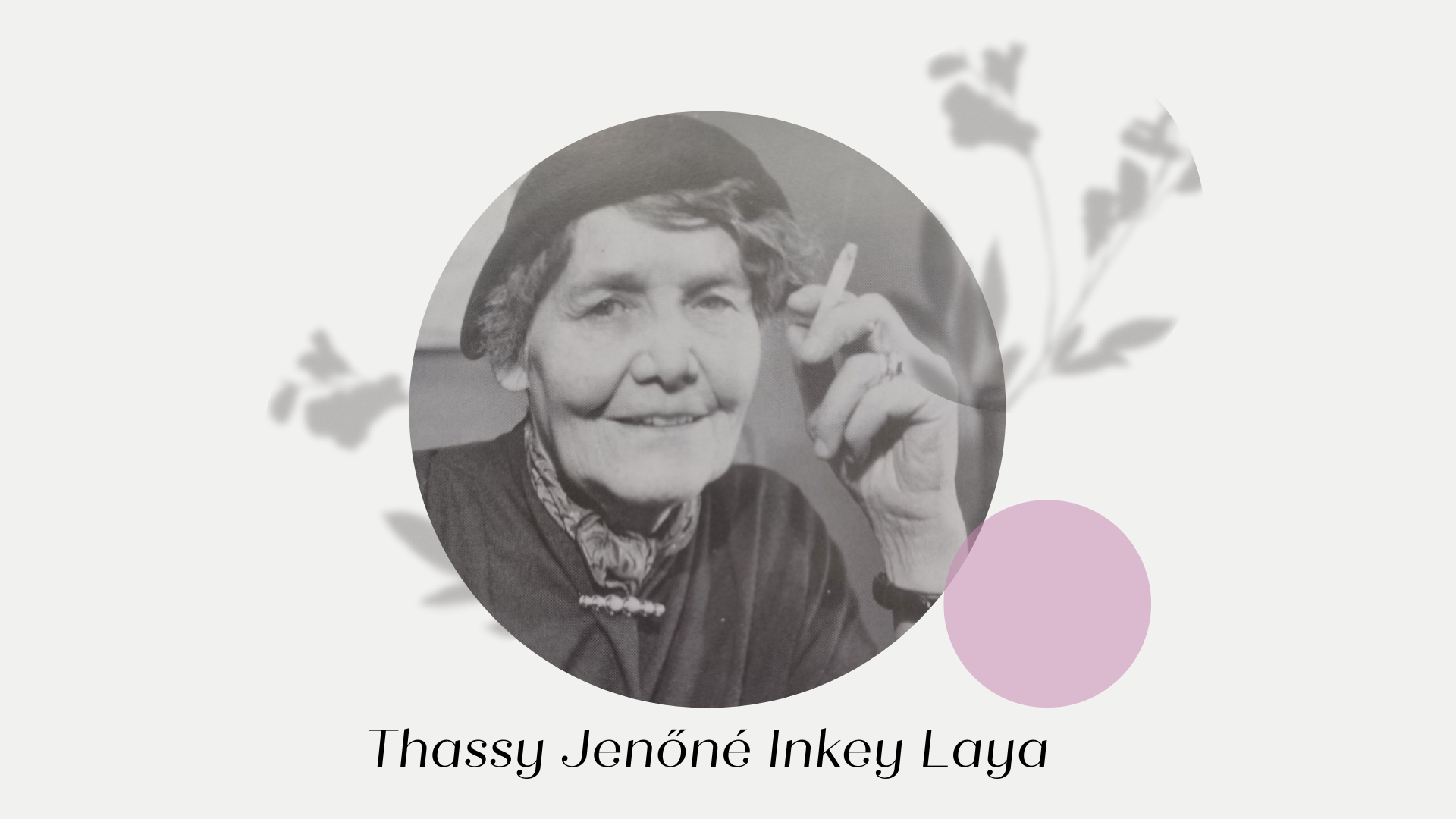

We can learn about the incomprehensible tragedies of Baroness Laya Inkey’s life from her son Jenő Thassy’s book. Serbs, Russians, murders, rape, deportation, emigration: these are the keywords that describe Laya’s ordeal. Yet nothing broke her willpower.

While pregnant, she was beaten with a rifle butt, shot in the lung, and her husband and four-year-old son were killed. All this happened in 1919, on a November night, in a mansion on the banks of the Drava River, which was broken into by Serbian soldiers. The story of Baroness Ladiszlája Inkey can only be pieced together from his son Jenő Thassy’s four-volume, page-turner autobiography. It consists of episodes such as an autumn night in 1919, when the occupiers attacked the peaceful family mansion.

Kisfaludy András (1998): Veszélyes vidék [Thassy Jenő]

Thassy Jenő 1920-ban született, régi magyar földbirtokos családban. Édesapját Dél-Magyarországon, Drávatamásiban levő kúriájában 1919-ben, még a trianoni határ megvonása előtt, szerb katonák megölték. Előbb a jezsuitáknál tanult, majd a Ludovikára került. Fiatal tisztként érte a háború.

Baron László Inkey and Countess Irén Zichy’s daughter, who was not at all beautiful but had received an excellent education, married Jenő Thassy against her father’s wishes and moved with him from the castle in Bogát to Drávatamási, near the Drava River.

Laya, as she was nicknamed in society, danced with the Andrássy girls, was a dancer with Pál Teleki and István Bethlen, competed in horse races, played polo, and guided Gladys Vanderbilt, wife of László Széchenyi, when she visited Hungary, because she knew English best.

She lost her mother at an early age and did not have a good relationship with her young stepmother, which may be why she was so keen on marriage. She did not choose well, at least according to her contemporaries, but she never complained about her husband, who often got into debt and was not very good at managing money.

‘That particular horror story took place during the turbulent times following World War I, when Serbs crossed the Drava River in hopes of looting’

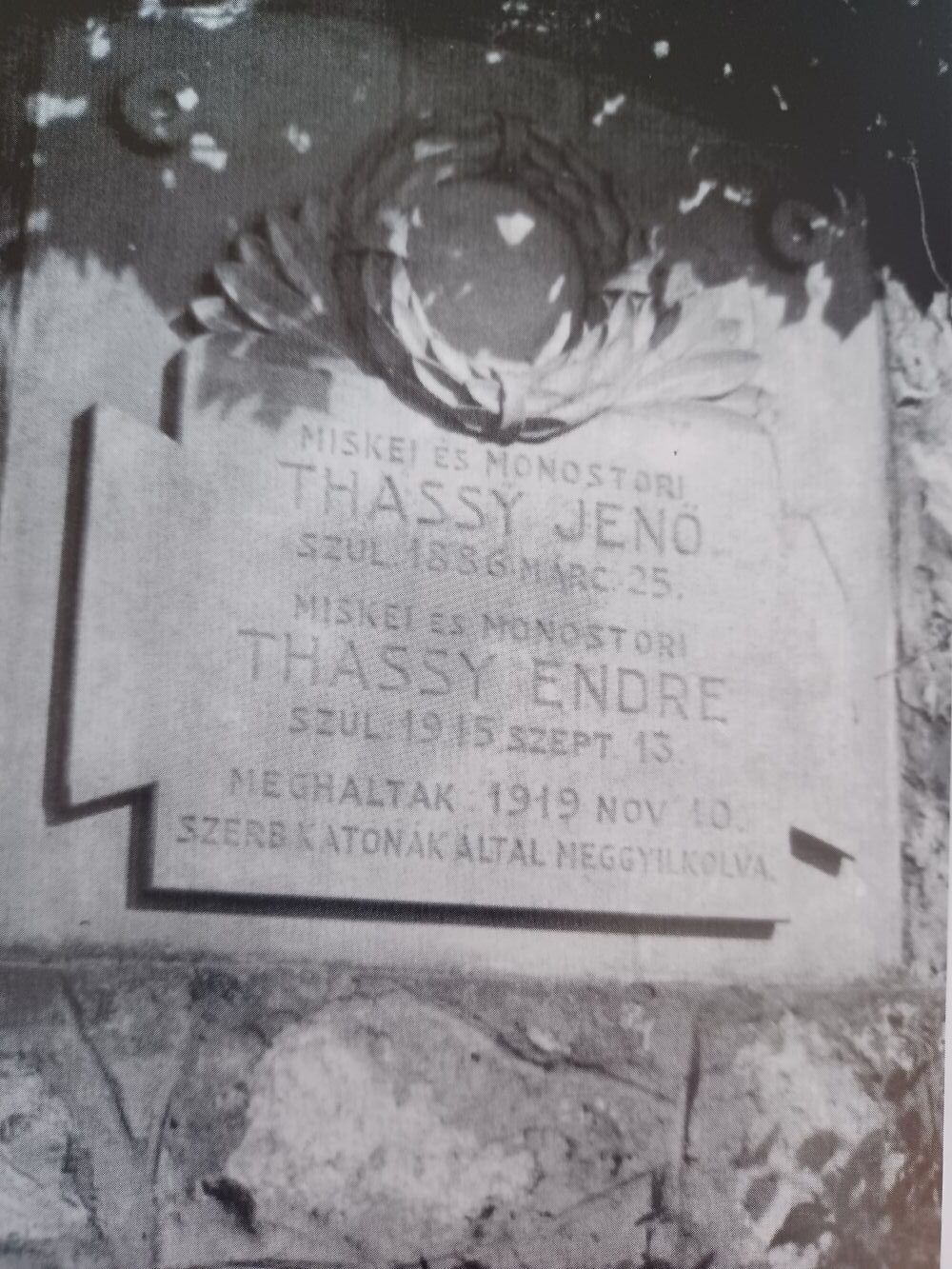

That particular horror story took place during the turbulent times following World War I, when Serbs crossed the Drava River in hopes of looting. On that terrible night, the attackers sawed through the door of the mansion and entered—nine of them in total. A stray bullet killed four-year-old Endre, who was lying in his little copper bed, and Laya’s husband was riddled with bullets. At the end of the bloodbath, the servants ran to the village for Dr. Kapolyi, who took the pregnant woman to the hospital in an ox cart and operated on her, saving not only her life but also that of her baby.

It would have been no surprise if Laya had never wanted to return to the scene of the tragedy, but she was made of sterner stuff. She raised her son in Drávatamási, a village of less than 700 souls, struggling to make ends meet because most of their family estates lay beyond the Drava River and were lost after the Treaty of Trianon. She had a capable manager, but he died too, trampled to death by a bull.

However, Laya was being stubborn, continued to live in the mansion, but every evening she walked around with a rifle on her shoulder, checking the locks, bolts, and shutters. She got up early, bathed in cold water, put on her indestructible linen suit, and began to walk around her diminished empire.

She decided that she had to preserve what she had left for her son. This otherwise scrawny but bright little boy first studied with the Jesuits in Pécs, then, at the family’s suggestion, was sent to pursue a military career. When he was stationed in Košice, Slovakia, during World War II, his mother also travelled there to be with him.

One would think that no more tragedy could fit into one human life, but the 20th century was not an era of mercy. As the front line approached, the woman was warned in vain not to stay on the estate, but she was unable to leave her remaining empire behind. The arriving Russians found her there. First, they shot the old guard dog sitting on the doorstep, then little Endre’s former playmate, a donkey. The woman was raped. The mansion was looted to such an extent that when Jenő Thassy returned home after the fighting, he did not even recognize the rooms. The beautiful porcelain-filled sideboard, the leather furniture in the salon, even the little bell that rang for lunch had disappeared.

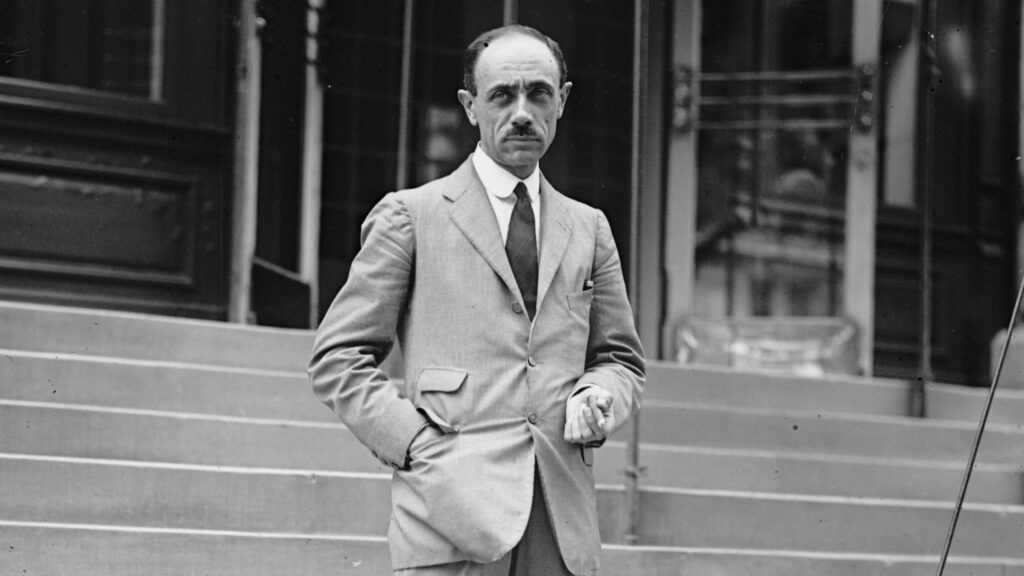

The young Jenő Thassy behaved magnificently during the Holocaust period. He was the one who rode his motorcycle to rescue Antal Szerb from forced labour, and it was not his fault that he failed. He hid Ferenc Karinthy and went to the ghetto to rescue Dr Kapolyi, who had saved his and his mother’s lives back in the day. His mother asked him to do this when she found out that they were being taken from their home and that the Jews in the village were being rounded up. She sent warm clothes and packages, and she regretted his whole life that he could not do more for them.

Kisfaludy András (2000): Özönvíz [Thassy Jenő]

Thassy Jenő második Magyarországon megjelent tényregénye az ostromtól 1946 decemberéig történt eseményeket dolgozza fel. Előbb a Budapesti Rendőrségen szolgál barátjával Görgey Guidóval olyan kommunista vezetők mellett, mint Sólyom László, Kádár János és Péter Gábor. Később Zsarnay Kálmán Pest megyei főispán munkatársa lesz, akit Rákosi emberei egy merénylet során életveszélyesen megtámadnak.

Mother and son spent the transition years in their apartment in Budapest. The young Thassy became a colleague of János Kádár in the newly formed police force and a subordinate of László Sólyom, who later became a victim of a show trial. Unsurprisingly, the atmosphere around him began to deteriorate over time, so he decided to emigrate. He returned home one last time to say goodbye to his father and his brother, whom he had never known.

‘Jenő Thassy Sr’s widow was declared a class enemy and deported’

His mother learned from the letters he cautiously sent home that her son had emigrated from Vienna to Paris and then to the United States. Thassy was a riding instructor in Central Park, a dishwasher in a restaurant, and then found work first at Radio Free Europe and later at Voice of America.

There, he received the news that his mother’s ordeal was not over. Jenő Thassy Sr’s widow was declared a class enemy and deported.

There was no crime in that century that had not been committed against her. She lived in a stable in Öcsöd, then in a storeroom, and at the age of 60, she had to work in the fields, but even from there she wrote to her son: ‘Don’t worry, there are good people here.’

At the end of 1956, Ladiszlája Inkey left Hungary, urged on and assisted by her friends and relatives. With only a few belongings, some of which she lost along the way, she crossed the border with a white sheet over her shoulders, stumbling through the deep snow. She arrived in Vienna with a small bag containing photographs of her loved ones, her glasses, her prayer book, and a rosary. There, she was reunited with her son. Old acquaintances, aristocratic friends, and relatives visited her at the hotel. But one morning she disappeared, leaving her key behind, and no one knew where she was. Her son feared the worst, but then she reappeared, her face flushed. She had gone to the cinema across the street and watched the movie Gone with the Wind.

Jenő Thassy left his mother in Munich for a while, saying that she should get used to the Western world before crossing the ocean. When she arrived in New York, the immigration officials scratched their heads because the tiny lady dressed in old-fashioned elegance did not have the necessary papers, but she was able to explain who she was in flawless English, and while inviting the gentlemen to tea, she proclaimed: ‘My son lives here in New York, don’t you know him?’

The setting for the last chapter of her life was the free world, the city of New York. Every morning, she set off on her explorations wearing a hat and gloves, with a bottle of water in her bag, which she always poured over a nearby thirsty tree. Another regular destination was the Hotel Plaza, where she would treat the horses in front of the carriages with sugar cubes. She took on dog walking and babysitting jobs—she wanted tasks for herself at all costs. She donated what little money she had to charity, paying for lunch for Hungarian refugees.

Baroness Ladiszlája Inkey of Pallini died in 1968 at Roosevelt Hospital in New York.

Related articles:

Click here to read the original article.