John (1386–1456)[1] became known in Italy and Central Europe as an influential orator of his time and one of the most prominent representatives of the radical Observant movement within the Franciscan Order. He spent most of his long life, spanning seven decades, in Italy, yet the last three years of his life, between 1453 and 1456, have determined the assessment of his entire life to this day. However, the life of Capistrano, a brilliant preacher who had close ties to the popes and was a disciple of St Bernard of Siena, who was canonized in 1450, raises a number of questions.

Today, his speeches against the Jews, and in particular his role in the trial against the Jews in Wroclaw, Poland, are the subject of some heated debate.[2] From today’s perspective, these are questionable, but in his own time, they were not considered unusual. The medieval Latin Church considered itself identical with society as a whole, in which Jews, in terms of their religion, could only be integrated as a foreign body, a tolerated community, in the hope that they would recognize their error and convert to Catholicism. Jews became the target of criticism not on racial grounds, but because of their religious beliefs and their economic activities resulting from their exclusion. This anti-Judaism was a defining belief for society and remained so until the modern era of emancipation. Indeed, the contemporary socio-economic vision of a society transforming into a just and pure evangelical community was only one, albeit important, aspect of the criticism of Judaism and, within that, of ‘Jewish’ usury.[3] However, this was not invented by the Franciscans; they merely took the lead in the policy initiated by the pope at the 1215 ecumenical council, which called for more radical action against non-Catholics and heretics.

It is not surprising that anti-Judaism, and sometimes explicit antisemitism, is a recurring theme in John’s sermons. On a theological level, his sermons were aimed at convincing Jews that they were misinterpreting their own Holy Scriptures, while at the same time encouraging the exclusion of Jews from daily social and economic life, their almost complete segregation, or even their removal. He encouraged princes to revoke the privileges granted to Jews and not to rely on their loans.

‘Jews became the target of criticism not on racial grounds, but because of their religious beliefs and their economic activities resulting from their exclusion’

Historians have devoted much attention to the tragic events in Wrocław, which, in their complexity, are a good example of how legends are formed. Capistrano began his preaching tour of Central Europe in 1451, arriving in Vienna, then denouncing heresy in Bohemia and Moravia, and spending the following year visiting almost every major city in Bavaria, Thuringia, and Saxony. From February 1453 to May of the following year, he spent a year in Wrocław, where he was welcomed with celebrations befitting a ruler.

John’s time in Wrocław coincided with a series of the most notorious atrocities against Jews of the time. During the court proceedings against them, 318 Jews from the city and the surrounding area were imprisoned, confessions were extracted from them under torture, and 41 Jews were burned at the stake, while the rest were expelled from the city, and their children who had been left behind were baptized. To this day, many blame the Franciscan monk for these events, but the reality is much more complicated than that.

Sources clearly confirm that the violent actions against Jews in Wrocław had no direct connection with the monk’s appearance. Surprisingly, on the instructions of the city council, Jews were arrested on charges of committing crimes against the Eucharist[4] just as John temporarily left the city, and even after his return, it was only two weeks after his return that the monk, who was skilled in law, was asked to take part in the ongoing trial.

It was Peter Eschenloer, the later clerk of Wrocław, who recorded the most unfavourable moments for John.[5] According to this, the monk himself gave the order to tie up the Jews naked, then have the executioners tear the flesh from their bodies with iron tongs, quarter their bodies, and finally put them on public display. The fact that torture and execution were common in heresy trials cannot be doubted, but the details have been shaped by oral tradition. Eschenloer himself was not in the city at the time of the trial and could only have learned of the events from later accounts. In the first Latin version of his chronicle, he writes nothing about John’s role, while decades later, around 1480, in the German version, he describes the monk’s role in horrific detail, holding him responsible for what happened, as he was not only present at the torture but also gave instructions on how to torture the accused.

Indeed, John preached regularly in Wrocław during Lent and Easter, which was always a critical period for Jews because of the commemoration of Christ’s crucifixion. At the same time, John’s speeches here were recorded, and we know that they were very restrained concerning the Jews, so no direct connection can be established between the speeches and the events. The events were much more manipulated by the members of the city council, who were drowning in debt and conducted the trial by excluding the ecclesiastical court, but took advantage of the presence of the highly respected monk.[6] However, court sources do not support the idea that John played a direct role in the torture in Wrocław. It is interesting to note that the bishop of the city was initially opposed to the prosecution of the Jews and himself questioned the charges. According to his surviving letters, he did not believe in the equal guilt of those imprisoned; moreover, he wrote: ‘I hear that some are completely innocent in this whole sad story.’ Even the future pope, Enea Silvio Piccolomini, had his doubts: ‘They say that all Jews in Wrocław were put in chains…I think this was invented to squeeze money out for the new king.’ Later, however, the bishop and John himself may have also believed the accusations and considered it justified to impose the harshest punishment customary at the time on the heretics.

‘Court sources do not support the idea that John played a direct role in the torture in Wrocław’

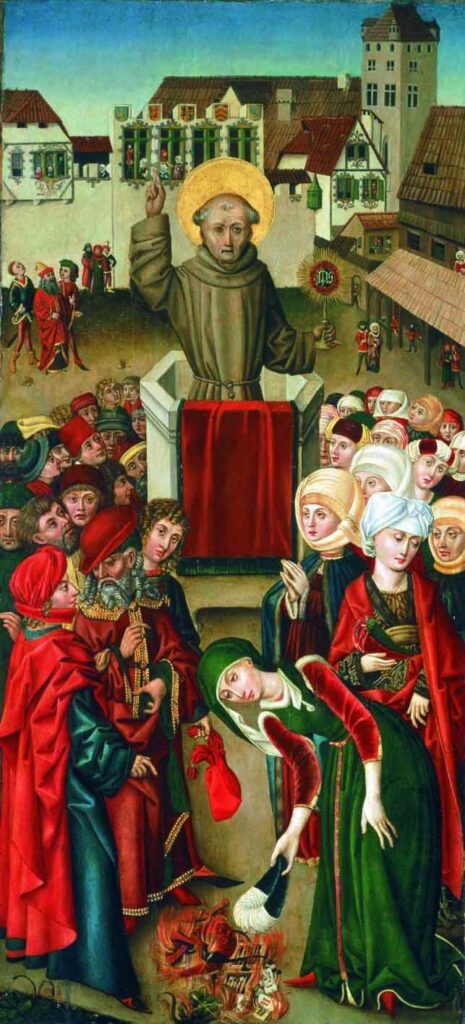

As the case in Wrocław shows, the picture that emerges from the sources is never just black and white, and it is not easy to navigate the web of ecclesiastical, political, and economic interests even in retrospect. Numerous monographs and studies in international research examine the relationship between mendicant orders, including John by name, and Judaism, as well as their responsibility in spreading virulent anti-Jewish stereotypes. However, reading John’s speeches, it can be concluded that he was not considered extreme among the Franciscans, but with his charismatic appearance and speeches—despite the use of interpreters—he was able to incite mass hysteria. His speeches were accompanied on countless occasions by miraculous healings and exorcisms, as a result of which his audience collected luxurious clothing, jewellery, and ‘immoral’ reading material and burned them on what was then called ‘the Bonfire of the Vanities’. Certainly, preachers were undoubtedly responsible for whipping up anti-Jewish sentiment in some cases, but they were only indirectly responsible for the atrocities.

When placed in the context of the defining events of Western church history, a more nuanced picture emerges. In the decades following the Council of Constance in 1418, which ended the Great Schism, and the Latin–Orthodox Church Union of 1439, preachers saw an unparalleled opportunity to reform Christian society and restore papal authority. This included harsh measures against the Hussites, Jews, Orthodox Christians, and Muslims. However, all this had little effect on John’s image in Hungary, where the fight against the Ottomans and the organization of a crusade became the primary concern.

From the second half of 1454, John was preoccupied with organizing a crusade. He took part in the German imperial diets in Frankfurt and then in Wiener Neustadt, and then, at the request of King Ladislaus V of Hungary (r 1440/1453–1457), he set out for Hungary to organize a crusade.[7] John clearly did not understand the role played by the Orthodox Christians in Hungary, primarily the Serbs, in defending the country, but he nevertheless went so far as to declare, renouncing his previous principles: ‘All those who want to help us against the Turks are our friends. We welcome Serbs, schismatics, Wallachians, Jews, heretics, and pagans if they want to fight with us in these difficult times.’

‘John’s performance in Nándorfehérvár in 1456 made him a prominent figure in Hungarian history’

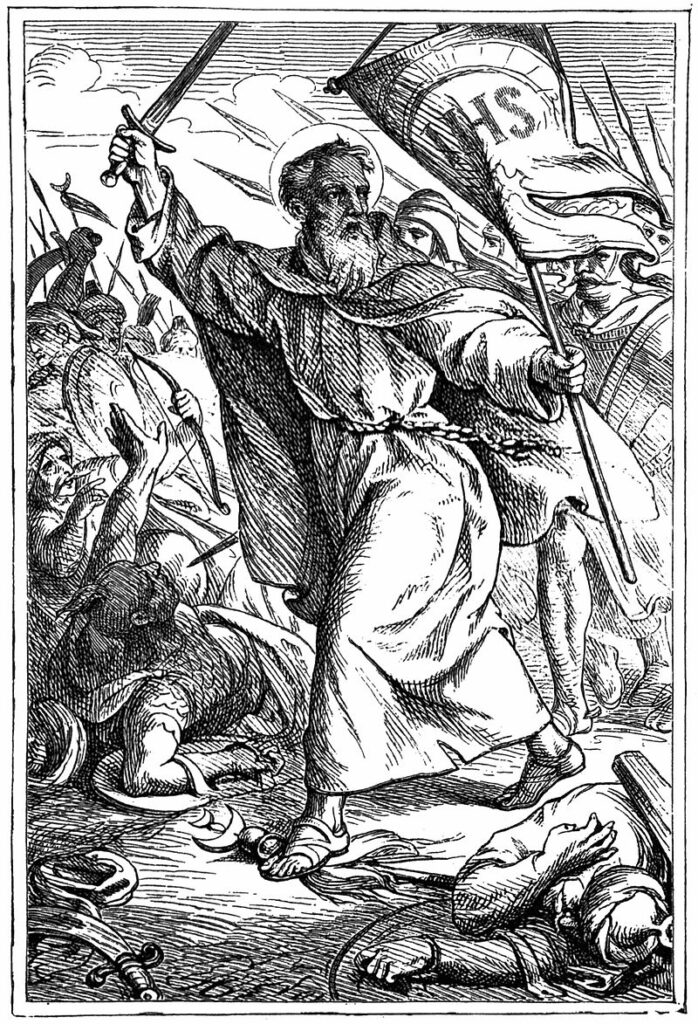

In July 1456 the Turkish Sultan Mehmed II led an army that attempted to capture Nándorfehérvár (now Belgrade, Serbia), the most important fortress of the Kingdom of Hungary. However, the defending army led by John Hunyadi defeated the besieging army, which then retreated. The crusader army of several thousand men recruited and led by Capistrano played an important, and according to Franciscan sources, decisive role in the victory at Nándorfehérvár. John’s performance in Nándorfehérvár in 1456 made him a prominent figure in Hungarian history, and the heroic stand of the crusader army he led, followed shortly thereafter by his death on 23 October, validated his life, which was not without controversy. His contemporary reputation in Hungary is well illustrated by the fact that after his death, his tomb in Újlak (now Ilok, Croatia) immediately became a place of pilgrimage, where nearly 500 miracles attributed to him were recorded until 1526. His canonization in the 17th century was also due to the success of the crusade and his veneration in Hungary. St John of Capistrano became a martyr of Christian Europe for the papacy and the Franciscans, and in Hungarian historical thinking, he became the saviour of the homeland, sharing this role with the victorious leader John Hunyadi, who also died near Nándorfehérvár. The year 1456 placed the veneration of Hungary in a completely different historical context and secured its place in the pantheon of Hungarian heroes to this day.

[1] Ital. Giovanni da Capestrano, Hung. Kapisztrán Szent János, Croat. Ivan Kapistran.

[2] Hanna Zaremska, ‘John of Capistrano and the 1453 Trial of Wrocław Jews’, in Paweł Kras and James D. Mixson (eds.), The Grand Tour of John of Capistrano in Central and Eastern Europe (1451–1456). Transfer of Ideas and Strategies of Communication in the Late Middle Ages, Warsaw–Lublin, 2018, pp. 149–168.

[3] Bert Roest, ‘Giovanni of Capestrano’s Anti-Judaism within a Franciscan Context’, Franciscan Studies, Vol. 75, 2017, pp. 117–144.

[4] A common accusation against those accused of heresy was that they did not believe in the real presence of Christ in the consecrated host and desecrated it in various ways.

[5] Halina Manikowska, ‘Eine erschreckliche Sache mit den Juden. Piotr Eschenloer o udziale Jana Kapistrana w procesie i kaźni Żydów we Wrocławiu w 1453 roku’ [Peter Eschenloer on the participation of John Capistrano in the trial and execution of the Jews in Wrocław in 1453], in H. Manikowska (ed.), Księga. Teksty o świecie średniowiecznym ofiarowane Hannie Zaremskiej, Warszawa, 2018, pp. 163–200.

[6] Heidemarie Petersen, ‘Die Predigttätigkeit des Giovanni di Capistrano in Breslau und Krakau 1453/54 und ihre Auswirkungen auf die dortigen Judengemeinden’, in Manfred Hettling, Andreas Reinke, and Norbert Conrads (eds.), In Breslau zu Hause? Juden in einer mitteleuropäischen Metropole der Neuzeit, Hamburg, 2003, pp. 22–29.

[7] Norman J. Housley, ‘Giovanni da Capistrano and the Crusade of 1456’, in Id., Crusading in the fifteenth century. Message and impact, Basingstoke, 2004, pp. 94–115.

Related articles: