19th-century Hungarian liberalism and progressivism have well-established historiography and canonised icons. However, the conservatives of the era are usually not well-known, or are even shunned by the public. Mainstream opinion accepts the liberal criticism of conservatism as default, and therefore it is crucial to have a more nuanced understanding of it.

Historical Background

The so-called ‘Reform Era’ of Hungary (1825–1848) saw tremendous changes in the political life of Hungary. Before the early 19th century, politics was largely non-ideological and ‘corporative’. It usually boiled down to disputes between the King-Emperor in Vienna and the noble estates, represented in the two chambers of the Diet (National Assembly) in Pozsony (Pressburg). While the Enlightenment and the French Revolution added some ideological elements to the discussion, it was only after the 1820s that political life became actually political.

The Reform Era’s traditional starting point is usually dated to 1825.

It was the opening year of the so-called ‘first Reform Diet’, the first session of the Diet of Hungary where progressive laws were proposed. At this time, the form of government in Hungary was still a mixture of a medieval corporative and an early modern absolutist monarchy. The Habsburg Kings could not promulgate laws without the Diet; however, they were able to veto the acts of the legislature and issue resolutions.

Furthermore, foreign and military policies were so-called ‘regal rights’, granting the Crown absolute power over those areas. On the other hand, since the budget was proposed by the Diet, military funding was often used as an effective bargaining chip. Before the 1820s, the aims of the Diet opposition were usually revolving around the autonomy and interests of the Hungarian nobility. These demands were widened in the Reform Era, hence the name which these decades are usually referred to.

The political landscape also saw a realignment during this period of Hungarian history. In prior decades, the main divide in politics was about the relation to the Crown, and thus the Habsburgs. The so-called ‘aulicus’ faction—usually recruited from the ranks of high aristocracy—was the ‘Court party’ of Hungary. It usually supported the King and was loyal to the House of Austria. On the other hand, the middle and lower nobility formed another faction, the ‘gravaminalist‘ (a term deriving from Latin, meaning roughly ‘a practice of grievance politics’) opposition, which was similar to the ‘Country party’ of traditional English politics.

These two proto parties were not the predecessors of the modern political parties, since roughly both thought along the same lines about society and the economy. In fact, the loyalist ‘Court party’ was oftentimes the more progressive one, siding with the enlightened absolutism of the Habsburg rulers.

However, in the 1820s, a radical realignment happened in politics. A liberal, reform-minded faction appeared, which mixed the idea of opposition to the Habsburgs with social and economic progress. This faction was represented by such celebrated Reform Era figures as Lajos Kossuth, Ferenc Deák, and Miklós Wesselényi.

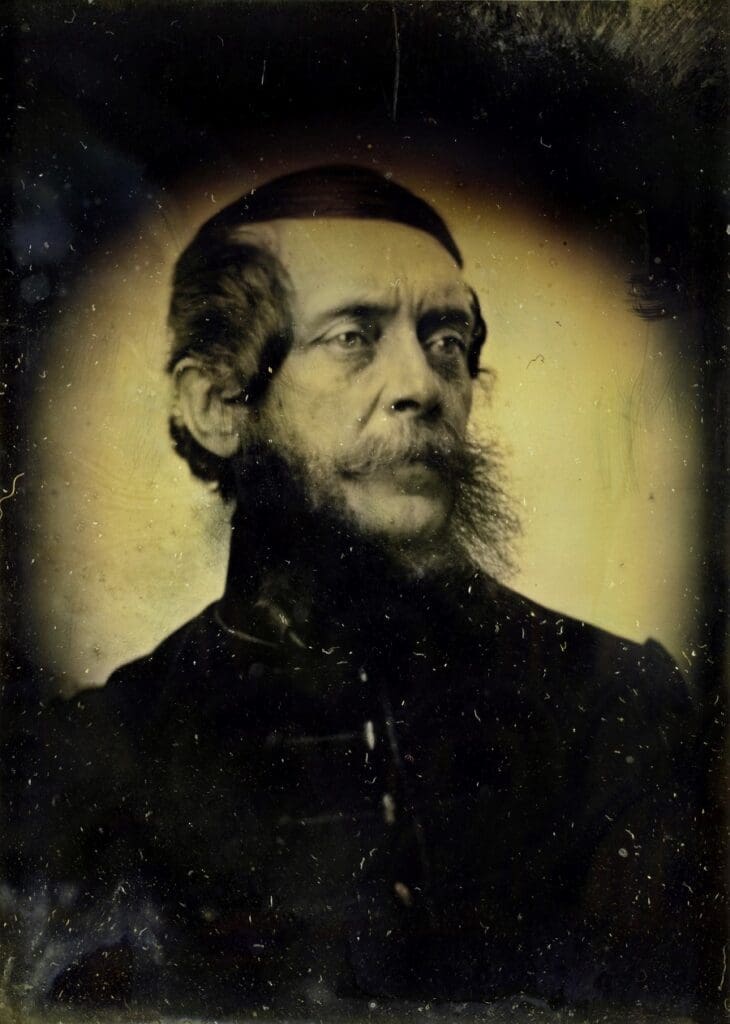

On the opposite side of the political arena stood the early Conservative faction, which opposed changes, aiming to preserve the privileges of the nobility. They are usually referred to as ‘csontkonzervatív‘ in Hungarian scholarship, which roughly translates to ‘conservative to the bone’ to distinguish them from the ‘cautious progressive’, or Young Conservative party. However, in this essay, I will refer to them as Traditional Conservatives. They were politically ‘reactionary’, but contrary to the progressive narrative, they were represented by talented and intelligent politicians, such as Supreme Judge, Earl Antal Cziráky. However, soon a third faction also appeared, which sought to reconciliate the Liberals and Conservatives on their values.

Aurél Dessewffy and the ‘Cautious Progressives’

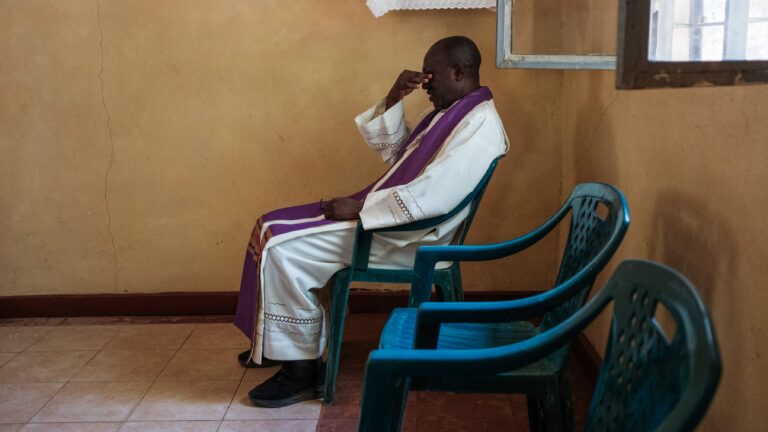

Count Aurél Dessewffy was probably the most important figure of early 19th-century Hungarian conservatism. He was lauded as one of the most talented among the young generation of politicians, even by his opponents. A gifted orator, writer, and politician, he passes away at the young age of 33. He became the leader of the group monikered as ‘cautious progressives’ or Young Conservatives.

This group was formed during the 1832–1836 Diet, when a group of young aristocrats decided to create an informal political party.

They found the Traditional Conservatives to be outdated in their ideas, and counter-productive in their approach. However, they also deemed the Liberals destructive and dangerous. Believing in organic development, they sought cautious reforms, in cooperation with the Royal Court.

The Young Conservatives were therefore fundamentally different from both the Liberals and the Traditional Conservatives, as well as the feudal factions, which were formed alongside the Country-Court divide.

First and foremost, they had a novel approach to the Habsburg-dynasty and the Crown. They wanted to coopt the more rational factions of the Vienna court for their cautious reforms. It is especially noteworthy that Aurél Dessewffy, similarly to István Széchenyi, was in direct contact with Prince Metternich, whom they both tried to persuade.

Dessewffy even sent a memorandum to the Chancellor, in which

he encouraged him to bolster slow and conservative reforms in Hungary, instead of tacitly siding with the Traditional Conservatives.

While the young aristocrats came from the ‘Court party’ tradition (often family tradition), they wanted more than just unquestionably siding with the Crown. Also, unlike the late 1800s josefinist supporters of Emperor Joseph’s radical reforms, they wanted to shape, not merely support, a reform agenda by the Vienna Court.

For this reason, they did not engage in legal disputes over the jurisdiction of the King and the Diet. They believed that the legal status quo must be preserved, seeing it as being derived from the medieval, ancient constitution of Hungary. A good example of this approach is how Aurél Dessewffy opposed granting county-level suffrage to university graduates, while also not dismissing the idea of enfranchisement ab ovo. He reasoned that such a reform can be beneficial, however, only if done on a national level, and via the legal channels, in accordance with the Crown.

The 1846 platform of the Young Conservatives states that they will support the government (meaning the Court) as long as it is ‘progressive and constitutional’, and that Hungary must preserve both its autonomy and ties to the ‘common Realm’. As the historian Zoltán Iván Dénes wrote about them—rather negatively—they wanted to defend the constitution not from the King, but from the liberal opposition.

The Young Conservatives also had a moderate approach to serf-emancipation.

They argued that immediate and full emancipation would destroy the economic basis of the nobility. Therefore, they proposed that nobles and serfs should be able to make individual deals, in which the serf would be emancipated, with his leased land becoming his own property, via a so-called ‘perpetual redemption’, and a sum of money be paid by the farmer to the noble in return.

To hasten this rather slow process, they proposed a bank loan programme, which would offer loans to the serfs to be able to pay the redemption. Emil Dessewffy—the brother of Aurél, who took over the conservative group upon the death of the latter—instructed the representatives of the party in the Diet in 1847 to support ramping up redemptions via loans.

Regarding equality before the law, Young Conservatives supported restricted suffrage. They wanted to extend voting rights to non-nobles, however, only with a high census, meaning that only the educated and high earners would be able to vote. This was proposed by Albert Sztáray, who argued that those who pay taxes ought to have a say in political matters.

The Young Conservatives supported the idea that in some way, the nobility—so far, exempt from it—should also pay taxes. For instance, Antal Széchenyi, in one of his speeches in the Diet said: ‘I support sharing the [tax] burden…All inhabitants of this country should contribute to the public fund.’

The aforementioned Sztáray, who was mainly concerned with tax issues, was also supportive of this idea. However, he also wanted to restrict and expand suffrage at the same time, along the lines of taxation and wealth, meaning that commoners who pay a considerable sum of tax should have suffrage, while impoverished nobles may lose it. Emil Dessewffy only supported indirect taxation of the nobles. These views boiled down to the 1846 Conservative platform, which called for expanded suffrage to tax-paying commoners, while also setting the taxation of nobility as only a long-term goal.

Futhermore, a very important component of their programme was tolerance toward ethnic and national minorities.

Dessewffy, for example, argued that forcing the Hungarian language on Slavic inhabitants of Hungary would only alienate them from the majority. Unlike the Liberals who hastened ‘Magyarisation’, the Conservatives were tolerant toward the nationalities. They also supported many pragmatic, almost non-political reforms. For example, their 1846 programme called for the development of infrastructure, regarding both cities and highways, as well as mining and military, and reforming the administration as well. They also supported easing punishments and reforming the court and penal system.

The Conservative Party and Further Developments

As noted above, the Young Conservative movement was led by Aurél Desswffy, an aristocrat, writer, and politician, after whose premature death the leadership passed to his brother, Emil Dessewffy. He was the one who transformed the movement into an actual political faction in 1846, under the self-evident name of Conservative Party,

creating the very first modern political party in the history of Hungary.

They released their written platform the same year, which called for the reforms described in detail above. They did not support the total overturn of the feudal and corporative system or aristocratic privileges. As historian István Schlett summed it up, they wanted neither capitalism nor constitutional monarchy, nor did they wish to preserve the old system without changes. Rather, they sought to reform the system, and slowly transform it into something new. They, therefore, took the Third Way position of a reformed corporative system.

The formation of their official party bolstered political life, presenting a challenge to the Liberals, who formed their own party, the Opposition Party in 1847. The Conservatives won the 1847 election; however, after the Revolution of 1848 and the April Laws, which created widened suffrage, they lost their majority in the Diet. Eventually, the party merged into the liberal formation in 1849. The group of these then-young aristocrats played a crucial role in the negotiations with the Vienna Court, which eventually led to the Compromise of 1867.

The Young Conservatives offered an alternative to both the Liberal and the Traditional Conservative agenda.

Instead of the extremes of resisting change to the bitter end or forcing it no matter what, they had a cautious and nuanced approach.

Their critics are probably right about this partly being due to their fear of losing their own privileges and status. Despite that, their activity was still an interesting and novel phenomenon in their historical era. The Young Conservatives wished to reconcile progress and tradition. Instead of creating a new social or political structure from scratch, they wanted to preserve and reform the existing framework.

According to historian Gyula Szekfű, had they been able to ally themselves with Earl István Széchenyi, one of the most important politicians of the era, they could have created a rational and sane ‘centre party’. However, instead of civic debate, the late 1840s were increasingly characterised by a feud between the absolutist elements of the Vienna court, and the more radical Liberals in Hungary, leading to the Revolution and War of Independence of 1848–49. The Young Conservatives, until recently, were alas forgotten or shunned by both historians and the wider public.

Related articles: