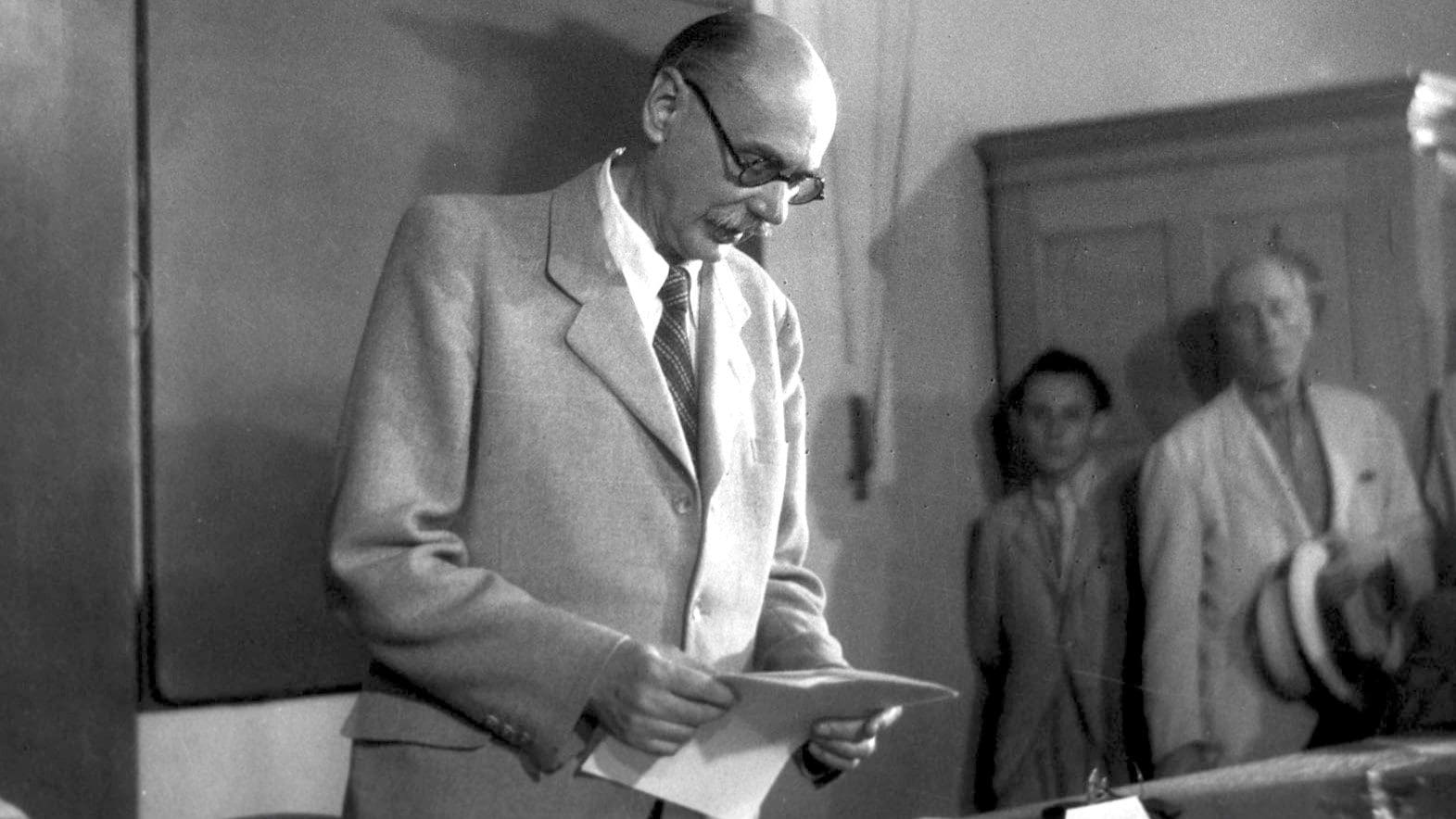

Gyula Szekfű, one of the most distinguished and influential Hungarian historians of the 20th century, was born 140 years ago, on 23 May 1883, and died on 29 June 1955, almost exactly 68 years ago.

He was brought up in a Catholic middle-class family in rural Székesfehérvár, graduated from the local Cistercian grammar school and then from the University of Budapest. In addition to the university, he was also admitted to the Eötvös József Collegium, one of the most prominent educational institutions of contemporary Hungary.

As an archivist in Vienna, Szekfű came to the attention of the public in 1917, the penultimate year of Austro-Hungarian dualism, when he wrote a book that broke with conservative taboos. As a novice historian, he provoked the traditional elites and won the sympathy of the radical left—and the left-liberal newspapers sympathetic to it—, such as the communist–anarchist Ervin Szabó, Andor Gábor or the liberal Lajos Szabolcsi, and the Nyugat journal.[1] The sympathy was mutual, as the young Szekfű had social-democratic and bourgeois–radical sympathies.[2] Yet, after only a few years—in 1921—Kunó Klebelsberg wrote this to the historian, a favourite of the radical left: ‘I know three books which properly confess the Christian course, your Three Generations, the An Outlaw’s Diary by Cécile Tormay and János Horváth’s From Ady to Arany’.[3]

The historian, who is regularly cited as a prominent figure of Hungarian conservative thought, is a fine example of a middle-class Hungarian intellectual who was shaken by the troubles and storms of the past century. But Klebelsberg wasn’t fully right. Horváth and Tormay’s books have not had nearly as great an impact on intellectual history as Szekfű’s Three Generations. Three Generations was, in a nutshell, a denunciation of the intellectuals of dualist Hungary, an indictment of the country’s ruin by the liberal classes, specifically capitalism and Jewry. Horváth considered

Szekfű’s writing to be an antithesis of the ‘Jewish-Calvinist’ ‘merchant spirit’.[4]

Szekfű described ‘capitalism’ as ‘having grown in size over time, becoming a more and more fearsome monster, creating factories and cramming hundreds of thousands and millions of people into the unhealthy, immoral air of smoky cities. And the longer the unrestricted freedom proclaimed by liberalism lasts, the more freely the capitalist big business devours the little ones, the more freely it exploits the economic weaklings, especially the workers.’[5] To this he added an entire chapter in his book, in which he denounced the relationship between Jewry and capitalism. Szekfű’s book, in which he also called for extensive worker protection and the regulation of industrialists by law, bears a striking resemblance to the basic tenets of socialism, with a certain Christian rhetoric added;

his work was therefore not only a model of Christian thought, but of Christian socialist thought.

In the preface to his book, Szekfű himself made no secret of the fact that he had already predicted the death of capitalism and the future of ‘the social planning of the state’ in 1917, but ‘three years ago, Hungarians shrouded in liberal illusions found these words alien, and they hardly had any resonance, except for some bourgeois–radical who started on at me as if I was some sort of dinosaur from before the flood’. But since the short-lived communism of 1919, ‘the Hungarian world has changed a lot, because everyone now agrees that the recent liberal past was an era of error.’[6]

Szekfű apparently saw in Bolshevism a sign of a kind of unstoppable social progress, which justified his thesis: capitalism leads to misery, and therefore the bourgeois system and its economic freedom must be broken with; instead, the direction of the greater role of the state must be followed. Ironically, Szekfű hinted in his book that he was not at all in tune with conservative theses. And although Szekfű himself did not want Bolshevism—only a ‘social republic’—, the Communists supported him, and he himself sympathised with the German Communist Revolution.[7]

Of course, Szekfű did not support left-wing political violence. In an exchange of letters with the above mentioned Andor Gábor, a Communist journalist, he wrote as follows: ‘During the time of the [1919] dictatorship you explained to me very calmly how to deal with the evil peasants who sabotage and boycott [the system]. Your words troubled me much but after all I am a historian so that I may understand the sad fact that even innocent people can, out of fanatism, draw swords and set out to massacre entire villages with guns and flame. But according to my humble civic ideology, one should not have sowed the seeds of comrade Bukharin’s ideology so strongly on the Hungarian soil, according to which, everyone must die who does not agree with him’.[8]

In 1930, he received a prestigious state award, the Corvin Wreath. From the late twenties to the end of the thirties, he was editor of a major conservative journal, and during World War II, he was openly critical of the policies of the Third Reich. He even penned an article for the Christmas 1941 issue of the social-democratic Népszava and testified for Communists in some trials. He was forced to go into hiding during the German occupation because of his wife’s Jewish ancestry.

After 1945, Szekfű turned against the interwar system and harshly denounced the rule of Horthy.

He even served as Hungary’s ambassador to Moscow from 1945 to 1948—

a role for which he is often criticised. In his book titled After the Revolution, published in 1947, he argued that in that particular situation there was simply no real possibility of a break from Soviet interests in the Central European region. In a sense, he returned to his roots: from budding socialist to conservative star historian, and then communist again…

[1] Iván Zoltán Dénes, A realitás illúziója. A historikus Szekfű Gyula pályafordulója, Budapest, Akadémiai, 1976, 83., 105., 110., 113., 135-136.

[2] Iván Zoltán Dénes, ‘Hóman Bálint és Szekfű Gyula kapcsolata’, 1913–1946, 2000, XXIII. vol., 1. no. (2011), 63-64., footnote no. 22.; Dénes: A realitás illúziója, 143., footnote no. 10.

[3] Krisztina Kollarits, Egy bujdosó írónő – Tormay Cécile, Vasszilvágy, Magyar Nyugat, 2010, 74.

[4] Dénes: Realitás illúziója, 166.

[5] Gyula Szekfű, Három nemzedék, Budapest, Élet, 1920, 85. and 212ff.

[6] Dénes, A realitás illúziója, 152-153.

[7] Dénes, A realitás illúziója, 143-147.

[8] The Archives of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Ms 4492/169, Szekfű to Gábor Andor, 28 June 1920.