Early years

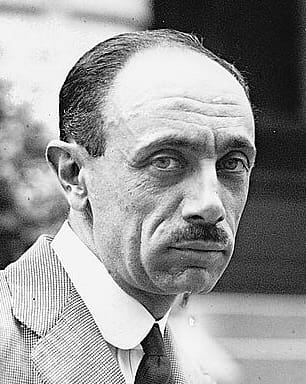

Pál Teleki was born on 1 November 1879 in Budapest. His father’s family was part of the Catholic Transylvanian aristocracy, while his mother was a daughter of a prosperous Greek merchant from Budapest.

During his early years, Teleki was homeschooled in Budapest, before being admitted to the Royal Hungarian University of Sciences (today ELTE). He read geography and law, as well as, for a short period, economics. During his university years, he published in geographical scholarly papers, and was active in the life of the Transylvanian high society. Furthermore, he also clerked at a court, and interned in his university’s department of geography.

Teleki obtained his doctorate in law in 1903. After concluding his studies, he travelled to Western Europe and to Sudan, conducting geographical research. Teleki also published a scholarly work on the geography of the United States, another country he visited. In 1913, he became a member of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences.

Teleki served as a frontline soldier during the First World War. However, he also used his knowledge in geography to serve his homeland.

Teleki was the author of the famous ‘carte rouge’, or ‘red map’, an ethnic map of Greater Hungary,

on which he designated Hungarian communities in bright and visible red. With the help of this visual piece of evidence, he tried to convince the victorious Entente powers at Versailles to take ethnic realities into account, and not maul the territory of Hungary as badly as they intended to. However, Teleki’s efforts, along with the brilliant speech of Count Albert Apponyi before the peace conference, were proven to be fruitless.

Interwar Years

After the end of WWI, Teleki emigrated to Switzerland. During the Hungarian Soviet Republic of 1919, he held offices in the various ad-hoc governments-in-exile. After the fall of the ‘Commune’, he returned to Hungary, and in July 1920, he was appointed prime minister by Regent Miklós Horthy.

An infamous episode of his premiership was the enacting the so-called Numerus Clausus. This law restricted the number of admissible students belonging to minority ethnic groups to their proportion in society; while the law did not mention Jews specifically, it was primarily targeted at them. (Editor’s note: The law was repealed in 1928.) But Teleki’s premiership was rather short-lived. When, in the spring of 1921, the exiled king, Charles IV attempted to return to the throne, Teleki was torn between his loyalty to the king and the regent, and he resigned.

From 1921 to 1927, he retired from politics, fully committing himself to science. He taught and researched geography at various universities in Budapest and continued his academic career. During this period, he also took part in the League of Nations study mission to Iraq.

Teleki also had an instrumental role in creating and sustaining scouting in Hungary.

He was the ‘chief scout’ of the country, and in this capacity, he organized the 1933 world ‘jamboree’, the global meetup of scouts. In 1927, Teleki was appointed a member of the newly re-established Upper House of the Parliament. Therefore, during the late 1920s and early 1930s, he stepped closer to politics and public life as well. Nevertheless, he did not assume any elected political position until the end of the thirties.

Return to Politics

In 1938, Teleki suddenly resigned his seat in the Upper House, and nominated himself for the House of Representatives. He gained a seat as candidate of the Party of National Unity, the ruling party of the Horthy era. Teleki served as minister of education in the government of Béla Imrédy, the radical right-wing prime minister. When Imrédy was forced to resign, Horthy requested the more moderate Teleki to take his place. On 16 February 1939, Teleki and his ministers took their oath.

Teleki renamed the governing party to Party of Hungarian Life, and slightly moderated its platform. The formation won the 1939 election—as was the case in every single election of these decades. (The party that ran under multiple names during its existence but is usually referred to as ‘Unity Party’ (Egységes Párt) had the playing field strongly tilted towards them, so their victories did not necessarily reflect the popular will.) However, the Nazi-aligned and far-right Arrow Cross Party also gained a huge number of seats. Apart from this outside threat, Teleki also needed to deal with the strengthening far-right faction of his own party. These voices demanded antisemitic restrictions, and closer alignment with Germany. Therefore, albeit Teleki tried hard to transform the party, and he himself was a strong advocate of Hungary’s Western, namely British, orientation, the friends of the Nazi German Empire were numerous among the political elite.

Drifting Towards War

In the late 1930s, Teleki again found himself being torn between multiple forces. He, just like almost everyone in Hungary’s political life in the 1930s, genuinely prioritized gaining back the territories Hungary lost in 1920 as a result of the Treaty of Trianon. And it was increasingly Germany who seemed to be open to border-correction. However, accepting help from Berlin naturally pushed Hungary into Hitler’s arms. The United Kingdom, from where Teleki actually hoped help would come, was not only hardly eager to assist Budapest’s revisionist efforts, but also made it clear that rapprochement with Berlin would not be tolerated.

In 1939, Hitler occupied Czechoslovakia. As its Eastern territory, Transcarpathia used to belong to Hungary before Trianon, Teleki made the unilateral decision to invade and reannex it. Furthermore, in 1940, he facilitated the Second Vienna Award. Via this decision, the great powers, in a move initiated by Germany (but assented to by London as well), ‘awarded’ the Hungarian-majority territories of Northern Transylvania to Hungary.

But Teleki’s second government did not only focus on foreign policy, but also implemented many important domestic policy decisions. During his tenure,

Teleki oversaw large-scale infrastructural developments, for instance the construction of railways in the freshly regained Transylvanian territories.

Furthermore, he also considered it important to boost the quality of the social welfare system, especially state support for families.

On the other hand, it was also under his premiership that parliament adopted the so called Second Jewish Law, which restricted the number of Jews employable in some prestigious professions. This law already reflected the domestic drift toward Nazi Germany. It was also aimed at appeasing the base of the Arrow Cross Party. Teleki’s role in the passing of the law cannot be whitewashed. He was a classic representative of what was known as ‘aristocratic antisemitism’, widespread during this era. Teleki believed that Jews are ‘foreign elements’ (as he referred to them during the parliamentary reading of the law) who need to be restrained in order to provide more opportunities to ‘Christian Hungarians’. At the same time, it must be stressed that he was strongly opposed to the full exclusion, let alone the annihilation of the Hungarian Jewry. Also, it should be remembered that very few in the Hungary of the 1930s were able to resist the temptation of -Semitism, even less so as such sentiments were also widespread all over Europe.

During the two years of 1938–1940, Hungary was pressured by Berlin, in exchange for its help in gaining back territories, to establish an ever closer diplomatic relationship. Hitler also forced the Central European nations to compete with each others for his friendship: if a country opposed him, it could expect less goodwill from Berlin in the settling of territorial disputes. With these factors in mind, under Teleki, Hungary also joined the Anti-Comintern Pact, and the Tripartite Pact, in 1939 and 1940, respectively. with those moves, Hungary became the de jure ally of the Nazi Germany.

The Tragic End

Teleki, on the other hand, drew a red line in appeasing Hitler. In 1939, when Germany invaded Poland, he bravely and flatly refused to join, or even to grant Germany access to Hungarian infrastructure in the process. His government also provided refuge to many Polish civilians, including Jews, and even soldiers, extraditing none to Hitler. However, it did not mean that Teleki did not also oppose Stalin. During the Winter War, his government armed and trained a volunteer battalion, which was sent to aid Finland.

In December 1940, Hungary signed a Treaty of Eternal Friendship with Yugoslavia. However, in 1941, the German-friendly government of Yugoslavia was ousted in a coup, which provoked a German attack, and Hitler requested Hungary to join the campaign. Hungary here, too, had a territory, Vojvodina, it wished to regain, which could provide a casus belli. But Teleki was warned by London that should Hungary join Nazi Germany in the Yugoslav campaign, Great Britain would declared war on it. The ever-honourable aristocrat, in addition, was also horrified by the prospect of the country violating a treaty that he himself had signed. Torn between duty and honour, under immense pressure, he committed suicide on 3 April 1941. In his suicide note, he warned strongly against Hungary entering the war: ‘We broke our word—out of cowardice...The nation feels it, and we have thrown away its honour. We have allied ourselves with scoundrels...We will become body snatchers! A nation of trash. I did not hold you back. I am guilty.’

After his death, Teleki was succeeded by the more German-friendly László Bárdossy, who assented to Hungary’s invasion of Yugoslavia.

His Legacy

Teleki’s legacy is highly debated to this very day. His left-wing and liberal critics continue to regard his antisemitism as the defining quality of his politics. This perspective anachronistically ignores the fact that during the era, antisemitism was part of the zeitgeist, and almost nobody could escape it.

Right-wingers, by contrast, emphasize his legacy as a conservative statesman, his breakthrough social programme, and the sacrifice he made by committing suicide to protest the war. He is often seen as a role model by those on the right, although he remains less popular than István Bethlen, his successor as prime minister in 1921.

Pál Teleki is undoubtedly an important figure of early twentieth century Hungarian history. Less prominently than Bethlen, but he also had a significant role in shaping the politics of the Horthy era. It must also be highlighted that he did try to resist the drift toward Nazi Germany, and

his desperately heroic final act makes him a martyr of the idea of Hungarian independence.

Related articles: