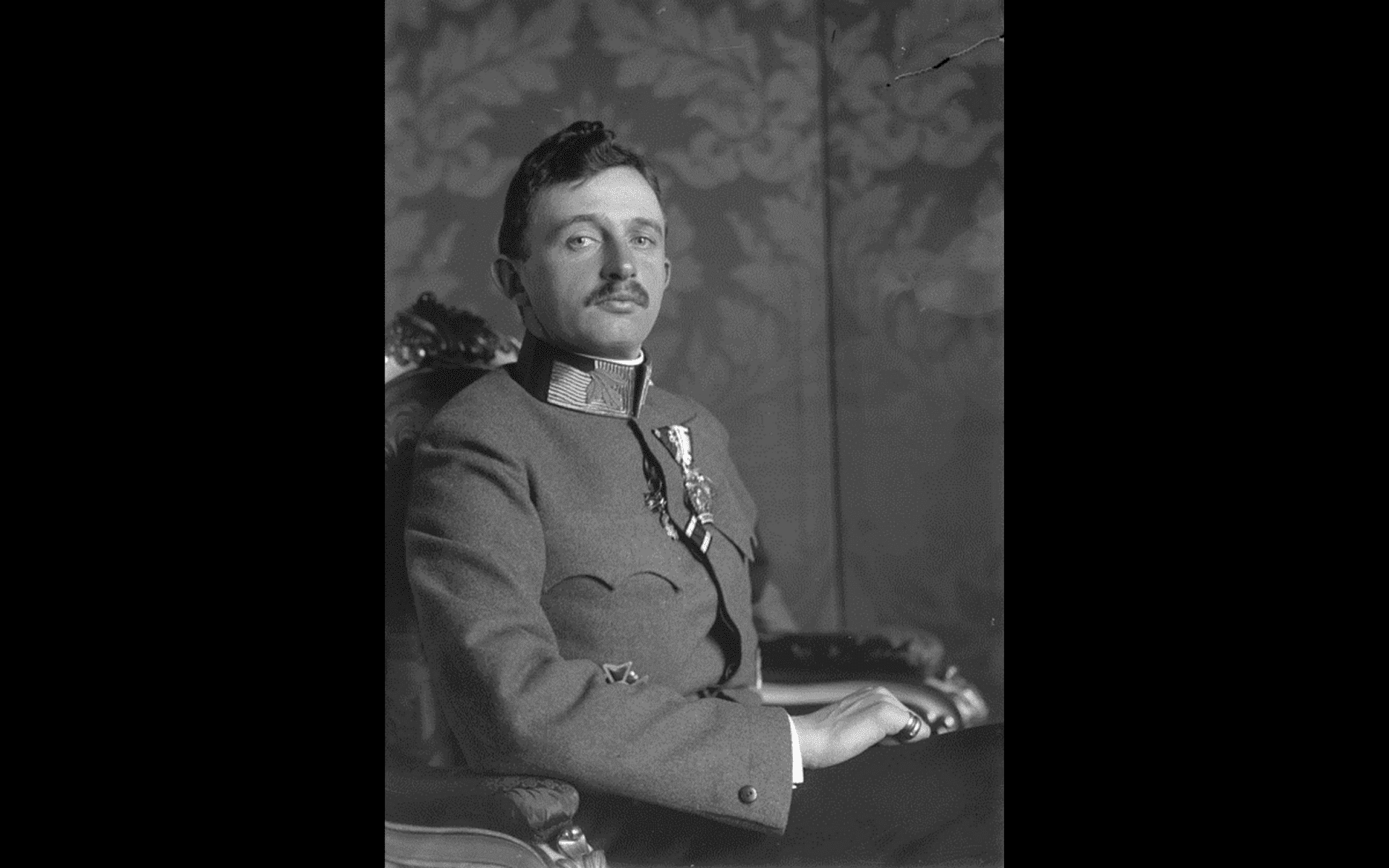

On the occasion of the coronation of King Charles IV (IV. Károly, or Emperor Karl I for the Austrians), the new King was greeted by the Neolog Jewish weekly Egyenlőség (Equality) as follows: ‘Hail to the Hungarian king, whose first promise is that he will guard equality before the law!’[1] The article recalled that Charles had already received the leaders of the Austrian Jewry before his coronation and made a statement to them: ‘The Jewish population has always demonstrated its loyalty and attachment to my House and their homeland, and even in today’s difficult times, it has been ready to sacrifice its blood and wealth to achieve successes with God’s gracious help.’[2] The article in Egyenlőség was not written from mere pragmatism. As rabbi Gyula Fischer highlighted in his synagogue speech reflecting on the ascension to the throne of the new ruler, Judaism commands toyalty to king: ‘We have heard the teaching: “The earthly kingdom is the reflection of the divine kingdom”. . . May our Heavenly Father…bless our Lord Charles IV, crown his life with light and majesty, adorn his forehead with the laurel of victory and glory.’[3]

However, Charles IV’s short reign – almost exactly two years to the day – was, according to the newspaper, ‘an era of Jewish glory and of Jewish tragedy.’ While the king sanctioned Albert Apponyi’s proposal of 21 December 1917 which would have given, among other things, a 25 million Hungarian korona state aid to the Jewish community (the bill was never presented to parliament), some great anti-Semitic scandals of the era also plagued his reign.[4] Charles spoke out against the pogroms in Upper Hungary in August 1918,[5] and in two successive governments he gave a ministerial portfolio – for the first time in the history of the country – to a Jewish politician, Vilmos Vázsonyi, and later appointed him as his secret adviser, despite his fear of how the Hungarian public would react.[6] This is how Vázsonyi later recalled his conversation with Prime Minister Móric Esterházy, who announced the news to him: ‘“Does the king know what religion I am?’’ “Yes, I told him, and the king replied: I don’t care what religion he is. The question is, is he a fair and honest person?’’’[7]

All of the above explain Egyenlőség’s assessment at the time of Charles‘ death that the last Hungarian king was ‘a true friend of our faith community.’[8] However, accusations of anti-Semitism formulated against the king in person, albeit mostly after his passing, cast a shadow over his rule. A Smallholder Party member of parliament Aladár Balla, for example, quoted by memory a statement allegedly made by the king: ‘King Charles…after ascending to the throne said…that the country has two major problems: Judaism and bankocracy’.[9] Albin Schager, a Viennese politician also mentioned Charles’s alleged anti-Semitism in 1925, an accusation which the personal secretary of the king strongly denied: ‘Ex-Emperor Charles never made any statements in front of anyone from which it could be concluded that he harboured antipathy towards Jews. [Anti-Semitism] earned him many unpleasant hours and annoyed him for weeks. I would rather say that he liked Jews. Several times I witnessed him conversing with Vilmos Vázsonyi on terms of true cordiality.’[10]

His relationship with Vázsonyi as his secret advisor was really close, as Arthur Polzer-Hoditz, the king‘s former chief of cabinet, recalled. According to him, when he was appointed, Vázsonyi tearfully promised to Charles that he would be loyal to him until the end of his life.[11] Vázsonyi kept his word, as he remained an active member of the legitimist movement – the movement dedicated to the restoration of the House of Habsburg in Hungary – until the end of his life, and he personally undertook the defence of Gusztáv Gratz and his legitimist co-defendants when they were tried for their actions during to the king’s return to Hungary (in what were known as ‘the royal coups d’état’, Charles attempted twice in 1921 to restore his reign in Hungary).[12] Vázsonyi, who had already drawn attention to the danger of Bolshevism as early as in February 1918 (!), found a worthy partner in his vehement anti-communism in Charles. At one point, the king said to him: ‘Well, you know best how much I support democracy, but Bolshevism is not democracy. It is an abomination! It is terrible! Please promise me that you will do everything possible against the insidious spread of Bolshevism. Be strict in this, because otherwise we will perish!’[13]

Vázsonyi spoke in support of Charles in the National Assembly after it declared the dethronement of the king and of the House of Habsburg in October 1921, saying that as the first Jewish minister, he had ’a double duty not to break the oath he made to the king.’ Vázsonyi upheld the legitimist idea until his death, and that is why Egyenlőség wrote about him that ’the son of a simple Jew takes the duty that devolved upon him from his noble position in public law much more seriously than any number of descendants of centuries-old noble families.’[14]

The collective memory of Hungarian Jewry – as well as of the Jews living in other territories of the former empire – has preserved a positive image of Charles. This is how Vilmos Vázsonyi called on his readers to mourn the king in April 1922: ’Let us weep for him as Hungarians, as citizens loyal to the country and sit in mourning for his death, because his love belonged to all of us and his soul knew no hatred.’[15]

Lajos Szabolcsi, the editor of Egyenlőség, wrote that Austrian, Czech and Polish have feelings of ’warm love and affection. . . towards the ruling Habsburg dynasty.’[16] He was not wrong: even in the early 1930s, it was customary among Austrian Jewish leaders to name their daughters after Charles’s wife, Queen Zita.[17] Even in the 1940s, there were Jewish anecdotes about the king spending the night in the houses of Jewish families in Transylvania during his visits. Tales circulated even about the Jews of Pressburg/Pozsony (today, Bratislava), who allegedly gave a goose on a silver platter to the last crowned king on St. Martin’s Day.[18]

The Legitimist movement supporting the restoration of the House of Habsburg had many Jewish members. Although the Zionist Zsidó Szemle (Jewish Review) remained purposely neutral on the issue, it could not help stating that there were ’truly outstanding individuals of Hungary’s Jewry are in the legitimist camp’.[19] Archduke Maximilian, Charles IV’s younger brother also said in 1933 that ’the Jews… stand by their ruler with enthusiasm. It is a special merit of theirs that they confirm this even now, when the Habsburgs are not in power. The number of Jewish citizens loyal to the king amounts to legions.’[20] Perhaps this is also why Hungarian Jews were accused of being pro-Charles or of having Habsburg sympathies by the popular nationalist anti-Habsburg camp, which also spread the rumour in 1921 that Charles was ’brought back by the Jews, because ’the Jews are all Habsburg loyalists, every single one of them.’[21]

The anti-Semitism of the anti-Habsburg popular movement may have also contributed to the Jewish community’s consistent support of King Charles. The Nazis later violently persecuted the Legitimists – as the idea of a Habsburg restoration was at odds with Nazi imperial policy – and thus article headlines such as ’Arrow Crosses Attack Legitimist Rally’ only reinforced Hungarian Jews’ support for the Habsburgs. On one occasion, when the Hungarian-Jewish politician Pál Sándor was speaking in parliament, pro-Nazi hecklers interrupted him thus: ’Enough of the Habsburgs! Enough of the 400 years of servitude!’[22]

Whether the rule of the Habsburgs meant 400 years of ‘servitude’ for Hungary is still a matter of debate. But it is a fact that even between the two wars, what Hungarian Jews remembered about the Habsburgs between the two world wars was the inclusive liberalism of a bygone era, the period of the first Jewish minister, as well as Jewish emancipation and acceptance.

[1] Egyenlőség, 30 Dec. 1916.

[2] Magyar Zsidók Lapja, 9 Feb. 1939.

[3] Egyenlőség, 13 Jan. 1917. For the talmudic quote: Berachot 58a.

[4] ’IV. Károly és a magyar zsidók. Mit jelentett nekünk IV. Károly kora?’, Egyenlőség, 9 Apr. 1922.

[5] ’IV. Károly és a magyar zsidók’, Egyenlőség, 17 Aug. 1918.

[6] Christopher Brennan, Reforming Austria-Hungary: Beyond his control or beyond his capacity? The domestic policies of Emperor Karl I, November 1916 – May 1917, London School of Economics PhD-thesis, 2012, pp. 308-309., footnote no. 36.

[7] Vázsonyi Vilmos, ’Meghalt a király. Emlékeim a királyról’, Egyenlőség, 8 Apr. 1922.

[8] ’IV Károly és a magyar zsidók’.

[9] Balla Aladár’s speech, 23 Dec. 1921. In: Nemzetgyűlési napló, 1920. Vol. XIV., p. 145.

[10] Új Kelet, 4 Nov. 1925.

[11] Egyenlőség, 21 March 1931.

[12] Csergő Hugó, Balassa József (eds.), Vázsonyi Vilmos beszédei és írásai’, Budapest, Vázsonyi Vilmos Emlékbizottság, 1927, vol. 2, pp. 369-376.

[13] ’Meghalt a király’.

[14] ’Vázsonyi Vilmos és a zsidó eskü’, Zsidó Szemle, 23 Dec. 1921.

[15] ’Meghalt a király’.

[16] Szabolcsi Lajos, ’Különös jelenetek a zsidók történetéből. A Habsburgok és a zsidók’, Egyenlőség, 28 Apr. 1934.

[17] ’Zita királynét és Ottót támadja Hitler lapja, mert „zsidópártiak”’, Egyenlőség, 20 May 1933.

[18] Magyar Zsidók Lapja, 8 Jan. 1942.

[19] Zsidó Szemle, 28 Oct. 1921.

[20] Egyenlőség, 11 March 1933.

[21] Zsidó Szemle, 4 Nov. 1921.

[22] ’Zita királynét és Ottót támadja’; Budapesti Hírlap, 20 Nov. 1932.