The following is an adapted version of an article written by Mátyás Bíró, originally published in Hungarian in Magyar Krónika.

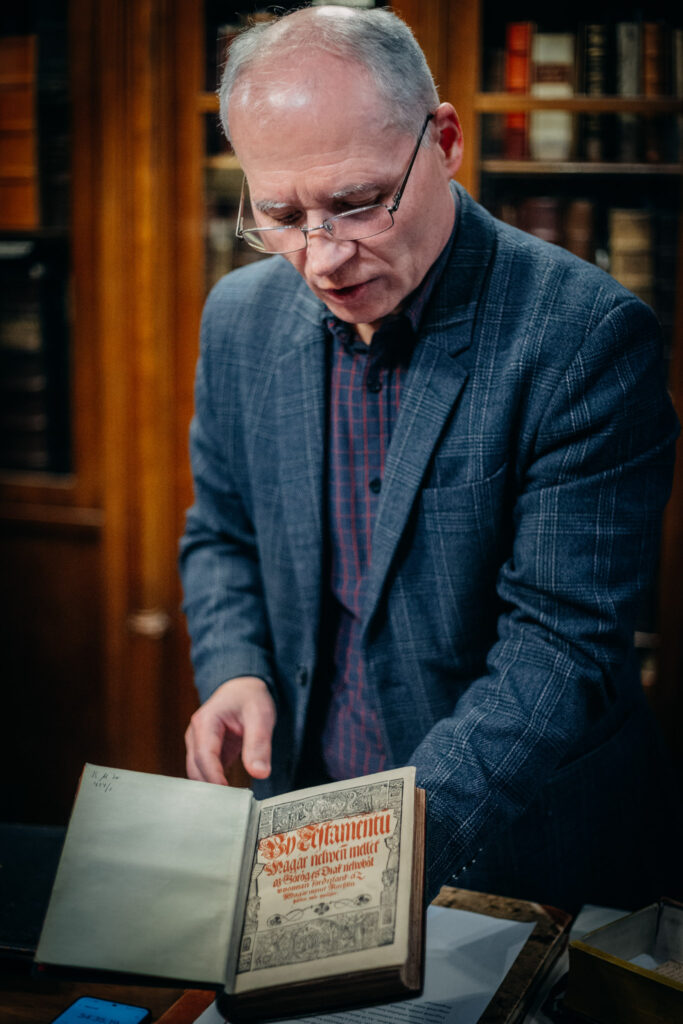

What is the difference between incunabula and antiquarian books? How did a page from the Gutenberg Bible end up at the Academy? What was the first book printed in Hungarian? Magyar Krónika spoke with literary historian Antal Babus, head of the Manuscript and Old Books Collection, which operates as part of the Library and Information Centre of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences.

***

When was the MTA library and manuscript collection established?

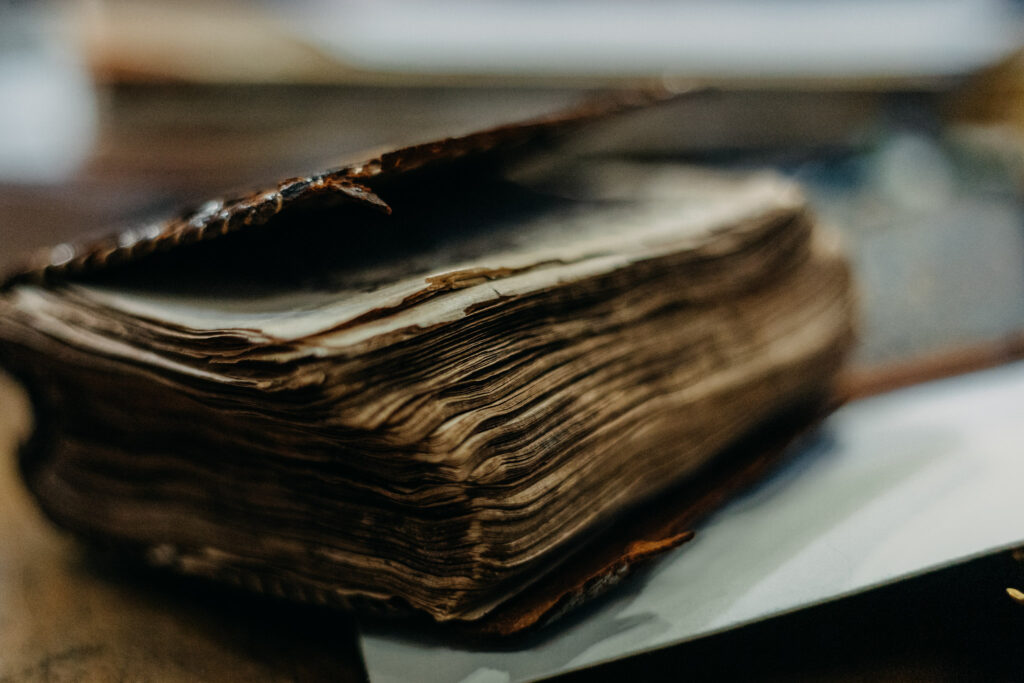

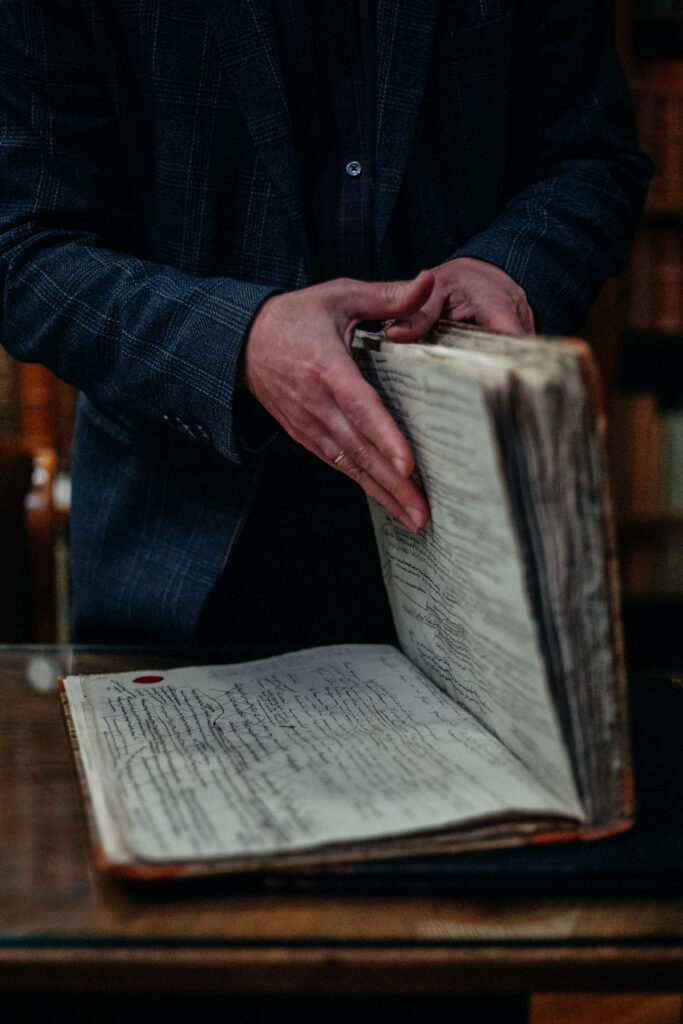

We have to go back in time to 3 November 1825, when a young hussar captain and member of the upper house, István Széchenyi, offered his annual income to the Hungarian Scientific Society at the Diet of Pozsony. It is very important that he did so in Hungarian. The announcement had an extraordinary impact and was enthusiastically welcomed throughout the country. Barely five months later, József Teleki, a descendant of the Teleki family of Szék, donated his family library to the society, which was of enormous value, containing 30,000 volumes. This would be a huge number even today, let alone at a time when book printing was on a different scale. Teleki also donated 600 manuscript volumes and more than 400 incunabula. This laid the foundations for the library.

What falls under the category of incunabula?

Books printed before 31 December 1500. According to international practice, volumes produced between 1 January 1501 and 1600 are referred to as antiquities. In our manuscript collection, the cutoff date was 1550, as determined by Csaba Csapodi, who reorganized the collection. In his opinion, printing became so widespread after 1550 that books produced at that time cannot be considered unique. We hold approximately 6,500 antiquarian books, but it is difficult to determine their exact number. Often, several books were bound together, which we call a colligatum.

How valuable is the collection of incunabula here?

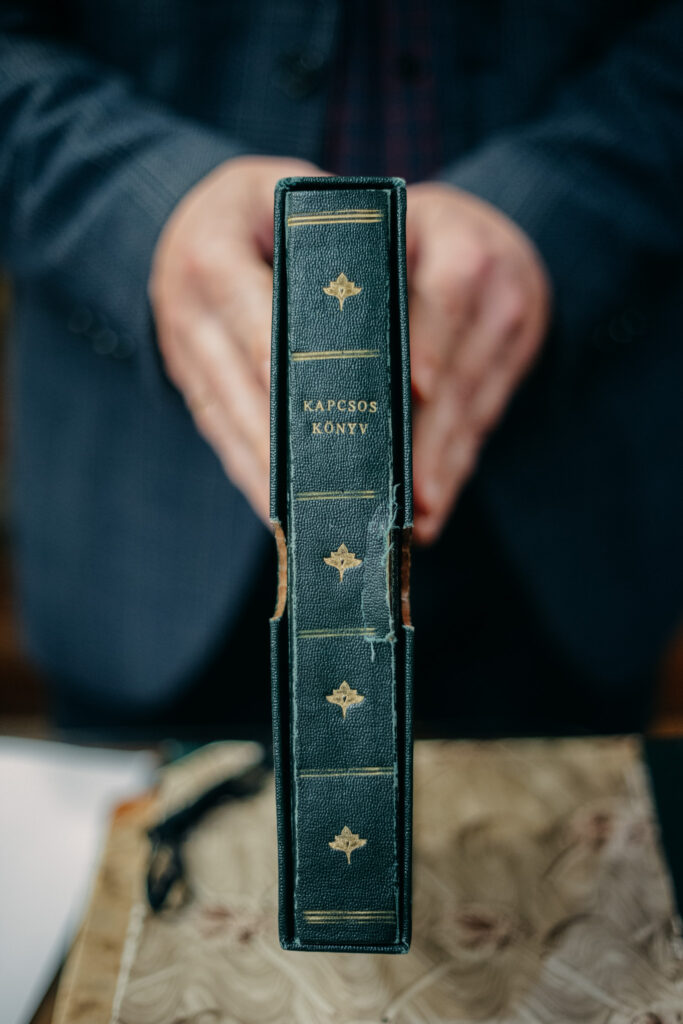

We have the second-largest collection of incunabula in Hungary, with 1,200 volumes. We received one-third of this, 409 volumes, from József Teleki, and later the collection was expanded through donations and purchases. In the 19th century, driven by patriotic enthusiasm, it was common for nobles to donate their libraries. For example, the Batthyány Library, including the Rohonc Codex, came to us in 1838. From the 1830s onwards, books flooded into the Academy. The manuscript collection has been operating as an independent department since 1861. Its first director was Flóris Rómer, a Benedictine monk and exceptionally well-educated scholar who also worked as an archaeologist and art historian.

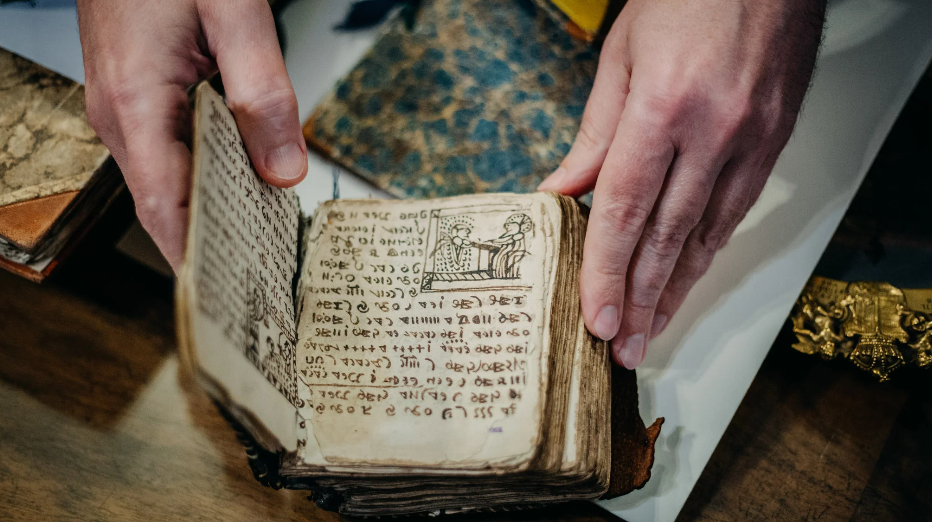

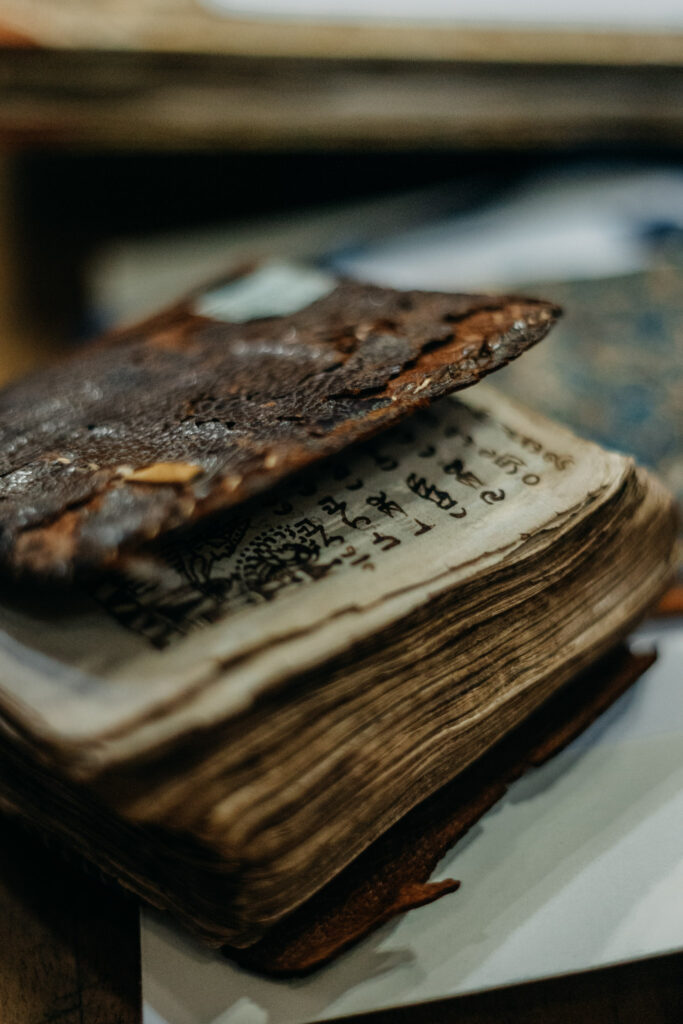

Why is the Rohonc Codex such a curiosity?

There are two codices in the world that researchers don’t know what to make of. One is the Voynich Codex, kept at Yale University, and the other is the Rohonc Codex. Since it came to us in 1838, people have been trying to figure out who wrote it, what it’s about, and what language it’s written in. It’s probably read from right to left, and more than 100 different symbols have been identified in it. European alphabets usually have 40 to 50 letters, so it is questionable whether the codex was written in a natural language at all. Some believe it was written in Sumerian, while others think the author was simply playing around. I don’t think that’s likely, as the codex is too thick for that. It is probably a sacred book, as it contains many drawings related to the Bible, crucifixions, and sun and moon symbols. I often tell my students that if anyone wants to become world famous, they should try to decipher it. A Spanish publisher is currently preparing a facsimile edition. 20 years ago, a replica was published in Bucharest, albeit without our permission. A Romanian historian ‘discovered’ that the codex was written in the Daco–Romanian language and that it tells nothing other than how the Dacians always defeated the Hungarians. The whole world laughed at this theory.

Besides the Rohonc Codex, the Érsekújvár and Kriza Codices are perhaps the best known in the collection. What else would you highlight?

The best-known codices in Hungary are the Korvinas from King Matthias’ library in Buda. We also have a Korvina, the Carbo Codex. In Europe, after the Pope, King Matthias had the largest library, probably containing several thousand volumes. Currently, we know for sure that only 216 books were part of it, including the Carbo Codex, copied in 1473. We also owe this book to József Teleki, who purchased it for the Hungarian Scientific Society in 1840. Incidentally, 1473 is also an important date in the history of printing in Hungary: it was then that the first Hungarian printing press was established under the leadership of András Hess. Unfortunately, we do not have a copy of his Chronica Hungarorum.

What are the most valuable pieces in the antique collection?

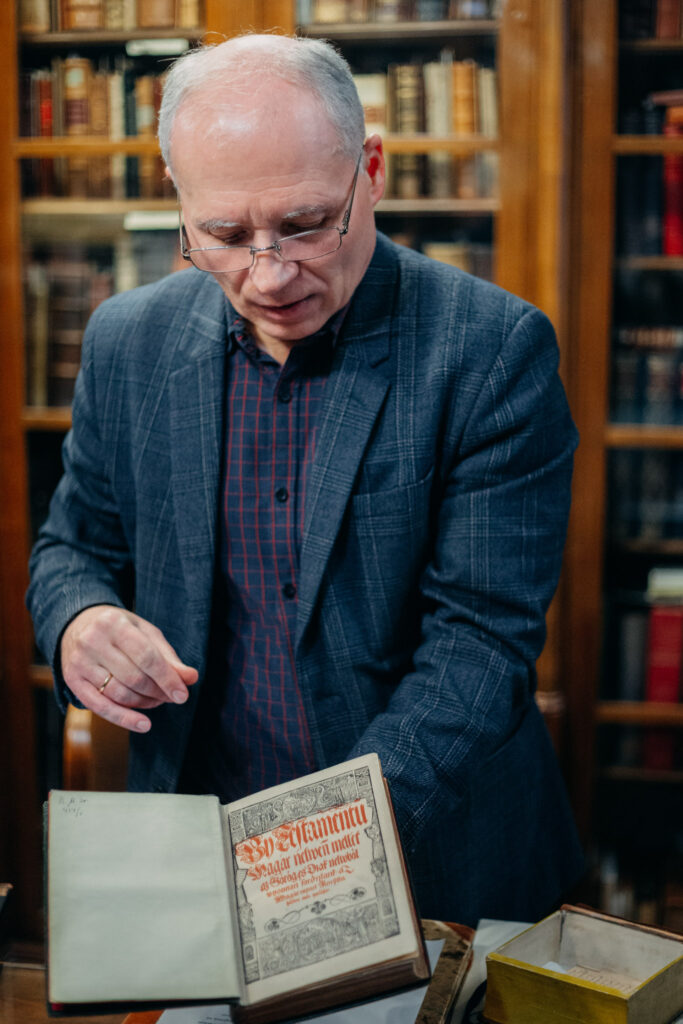

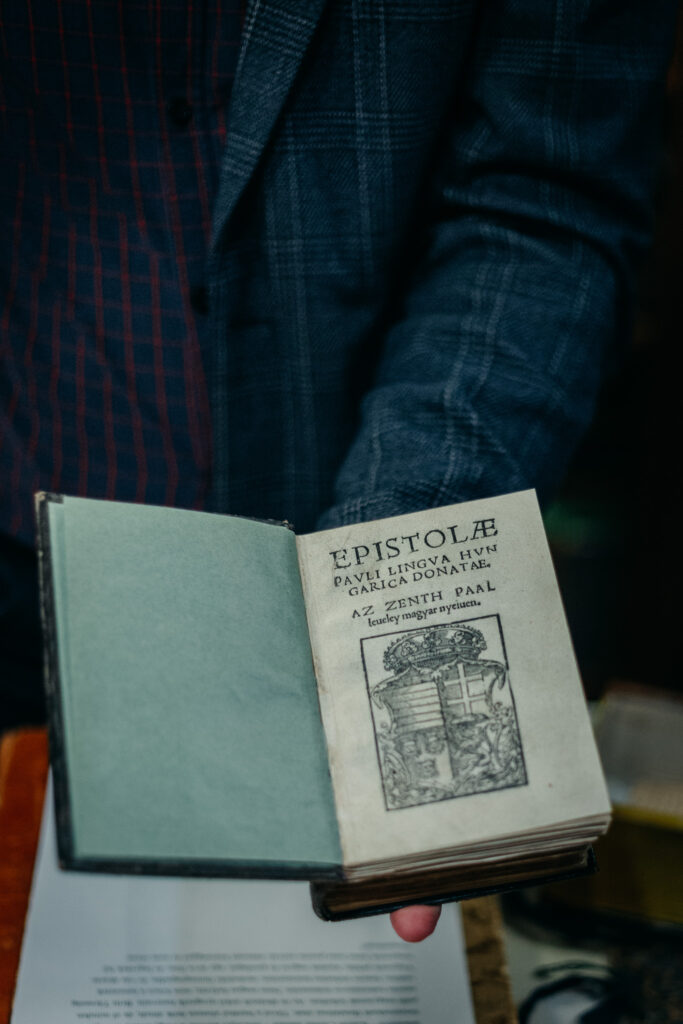

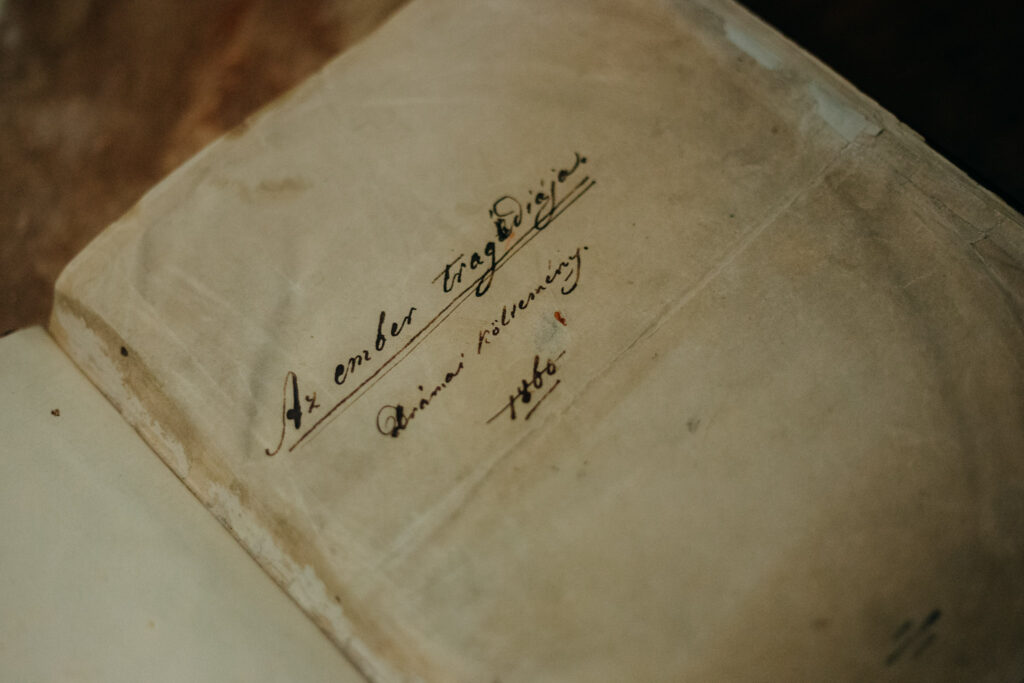

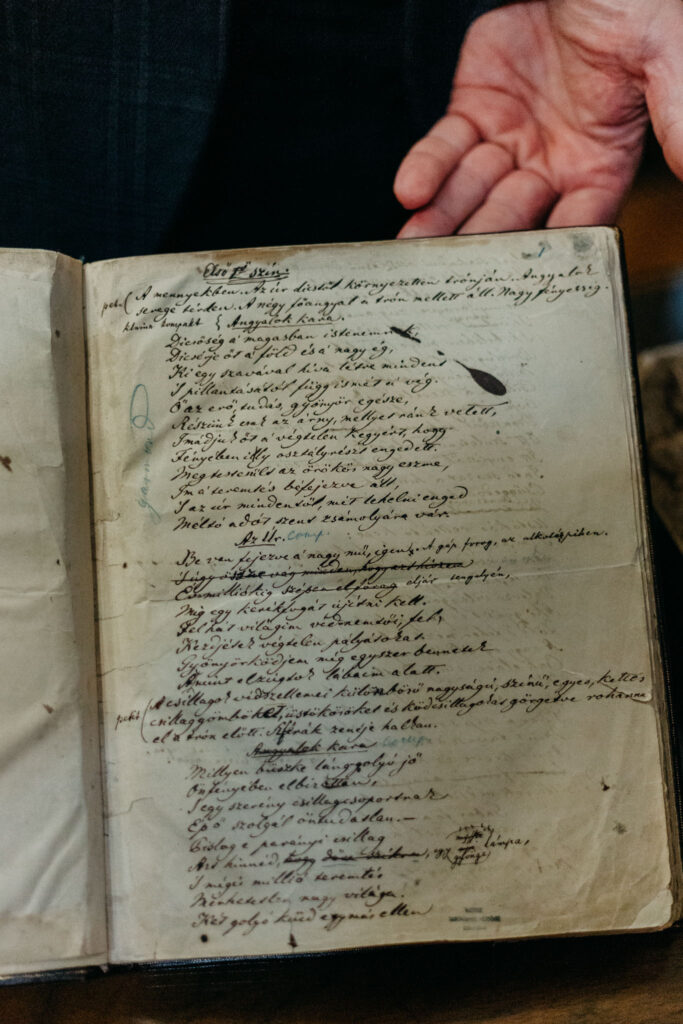

The first Hungarian printed works are of great importance. Following András Hess’ printing press, turbulent years marked Hungarian history, so the next domestic workshop that printed in Hungarian did not emerge until 1541. This was Tamás Nádasdy’s printing press in Sárvár. Until then, Hungarian-language books were printed abroad, in Vienna or in Kraków, close to the Hungarian border. In 1533 the first book printed entirely in Hungarian was produced in the latter city, at the printing house of Hieronymus Vietor: the letters of St Paul, translated by Benedek Komjáti. Komjáti was the tutor of Gábor Perényi, a nobleman who died in the Battle of Mohács. At first, he was reluctant to take on the job because he did not feel his knowledge of Ancient Greek was strong enough, but eventually, at the encouragement of Perényi’s widow, Katalin Frangepán, he translated the texts in Nyalábvár, Ugocsa (a county in the northeastern part of the Kingdom of Hungary). The widow also financed the printing of the work. Komjáti was a follower of Erasmus of Rotterdam, who encouraged people to read the New Testament in its original language, and thus played a role in establishing book culture and the Reformation.

‘We owe the first Hungarian printed works to two aristocratic families’

Gábor Pesti, who translated the four Gospels, was also a follower of Erasmus.

That’s right, we also have his New Testament. It is an important work, written in very beautiful language. János Sylvester also belonged to this humanist-Erasmian circle. He went from Kraków to Sárvár and persuaded Tamás Nádasdy to establish a printing press. Along with Sylvester’s translation of the New Testament, a copy of which we also have, unfortunately, only three books were published in Sárvár, after which Sylvester became a professor in Vienna. The significance of his work is that it is the first book printed in Hungarian in Hungary, with a print run of 100–200 copies. It is beautiful. In fact, we owe the first Hungarian printed works to two aristocratic families.

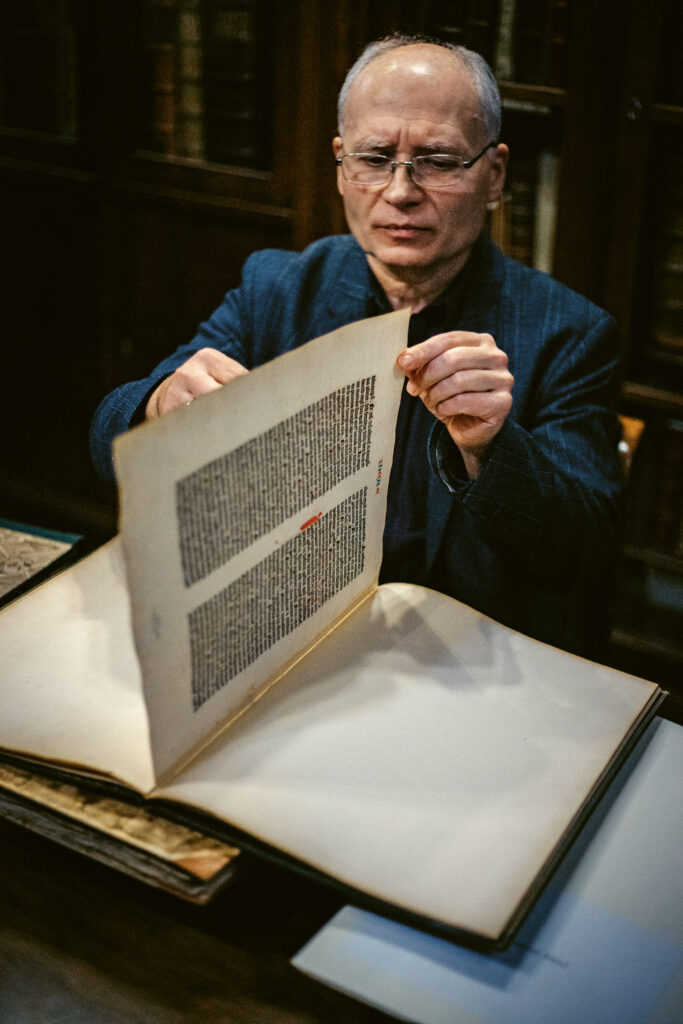

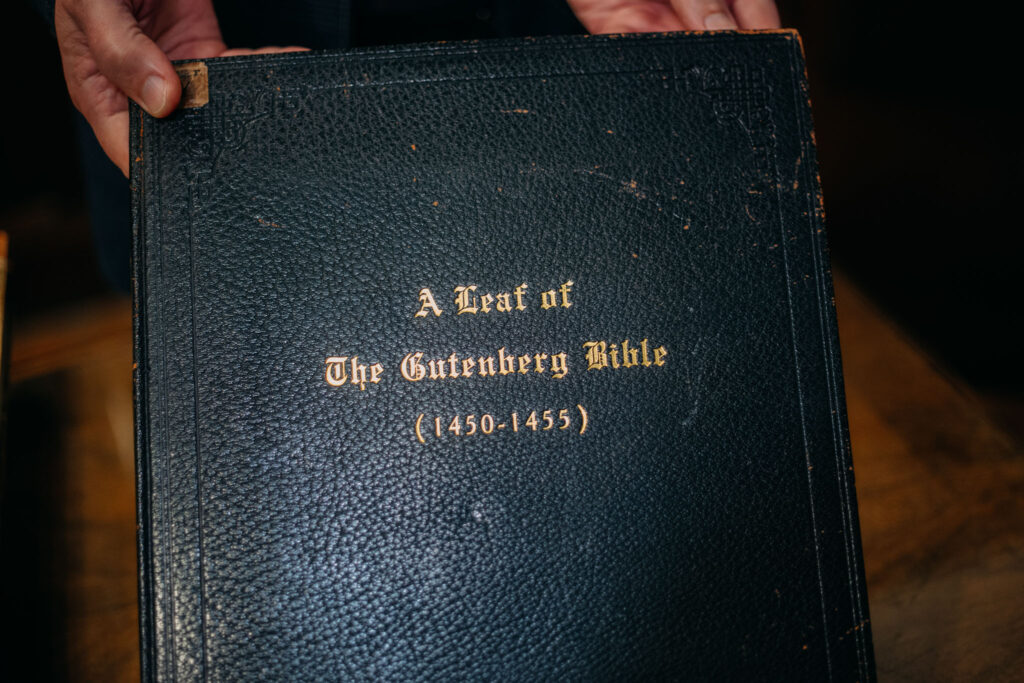

You showed us a real rarity: a page from the Gutenberg Bible, which is also preserved here.

To be a little inaccurate, it is a page from the world’s first printed book. But this is both true and not true. Gutenberg had previously printed smaller calendars, which were his first attempts. However, this 42-line Bible is his most beautiful work, printed in Mainz around 1456. 200 copies were made, 35 of which were printed on parchment. He tried to convince potential buyers that a printed book could be as beautiful as a codex. He left space for the initials, and they were drawn by hand. This is a fine example of the transitional period when codices and printed books coexisted. Our copy is printed on paper.

How did you acquire it?

It’s very simple: we received it as a gift. There was an American art dealer and antiquarian named Gabriel Wells, who was born in Hungary as Gábor Weiss. He had a business idea: if he took the Gutenberg Bible apart and sold it page by page, he could make a lot of money. He donated one page to the Hungarian Academy of Sciences in 1921. We are grateful to him for this, even if the procedure is somewhat controversial.

‘Digital culture is gaining ground…the two cultures will coexist for a long time to come’

As a literary historian and head of the collection, how do you see the role of printed publications?

We are witnessing a change similar to that seen in Gutenberg’s time. Digital culture is gaining ground, but I don’t think it threatens to replace paper-based books; the two cultures will coexist for a long time to come.

It may come as a surprise, but the number of printed books is still growing today; there is a demand for them. Jorge Luis Borges writes that when he received the Brockhaus Encyclopedia as a gift, he was already blind, but he enjoyed feeling the volumes, having them there beside him. Books are meant to be felt, not just read.

Related articles:

Click here to read the original article.