The following is a translation of an article originally published in Hungarian in Magyar Krónika.

Five rooms, a thought-provoking narrative arc, symbols, yellowed letters, contemporary installations. Széchenyi’s porcelain inkwell, Ferenc Pulszky’s document wallet, Katalin Karikó’s Nobel Prize.

Inspired by Széchenyi’s 1842 speech, the National Museum’s new exhibition—Varázshatalom — Tudás. Közösség. Akadémia. (Magic Power — Knowledge. Community. Academy.)—goes beyond the usual summaries of the history of science. It presents the role our scholarly society has played in national history and in society at large, and the path through which our language became one of the valid languages of science.

One could say that while our national history has often been marked by turmoil, the history of our science has been a triumphal march. Thanks to our unique language and deeply individualistic mindset, Hungarians are well-suited to embody what Albert Szent-Györgyi described as the essence of all discovery: ‘To see what everyone else sees, but to think what no one has thought before.’ Since the time of King Matthias, great minds had long aspired to establish an academy—Béla Mátyás, Péter Bod, and György Bessenyei all dreamed of it—but it was through Széchenyi’s will that their vision finally came to life. That was exactly two hundred years ago.

‘To see what everyone else sees, but to think what no one has thought before’

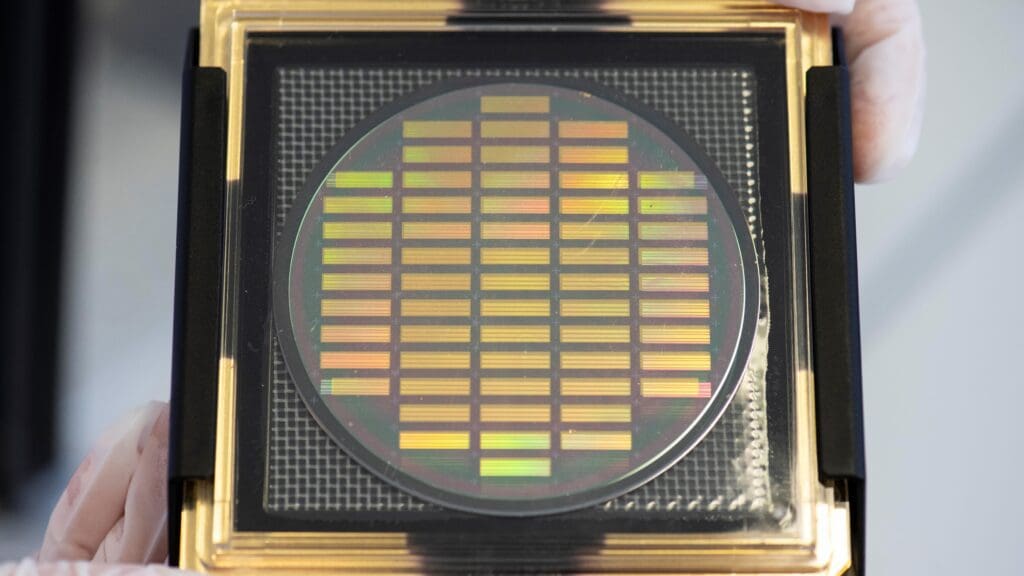

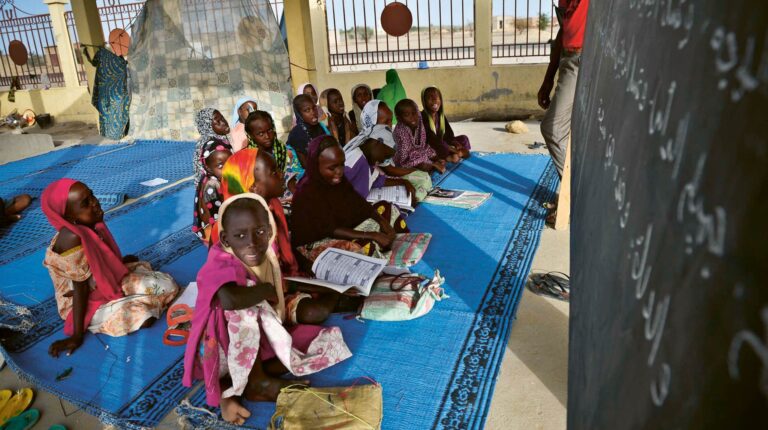

Alongside scientists’ personal belongings, tools of their trade, and portraits, the exhibition features a touchscreen that offers an overview of the history of science throughout the entire Carpathian Basin. This is why, although the five exhibition rooms are not particularly large, visitors often find themselves spending hours inside. Light, darkness, and colour all carry meaning; even the time-worn portraits surrounded by clicking gears suggest that everyone has contributed—everyone helped turn the wheel forward. Bartók’s hurdy-gurdy, a lecture by Botond Roska, the Gömböc, laser images, and marble busts together represent the sense of continuity.

Erzsébet Andics was the first female academician. After the fall of the Hungarian Soviet Republic, the political blacklisting of scientists began. Ferenc Toldy was the first person to lie in state at the Academy’s headquarters, inaugurated in 1865. These, too, are milestones—though of a different kind than scientific breakthroughs. They reveal how the academic body has never been, and perhaps could never be, entirely independent. Even Széchenyi expressed dissatisfaction with contemporary leaders, while Klebelsberg warned against the overreach of the state. Every era brought its own challenges. Difficult times were often followed by even harder ones. There were moments when the Hungarian language itself had to be defended; others when science had to fight off the deception of pseudoscience. State dictatorship, lack of funding—all formidable adversaries. And now we face artificial intelligence—but not as an adversary. Why not? That becomes clear at the very end of the exhibition.

The exhibition Magic Power — Knowledge. Community. Academy. is on view at the Hungarian National Museum until 26 October.

Related articles:

Click here to read the original article.