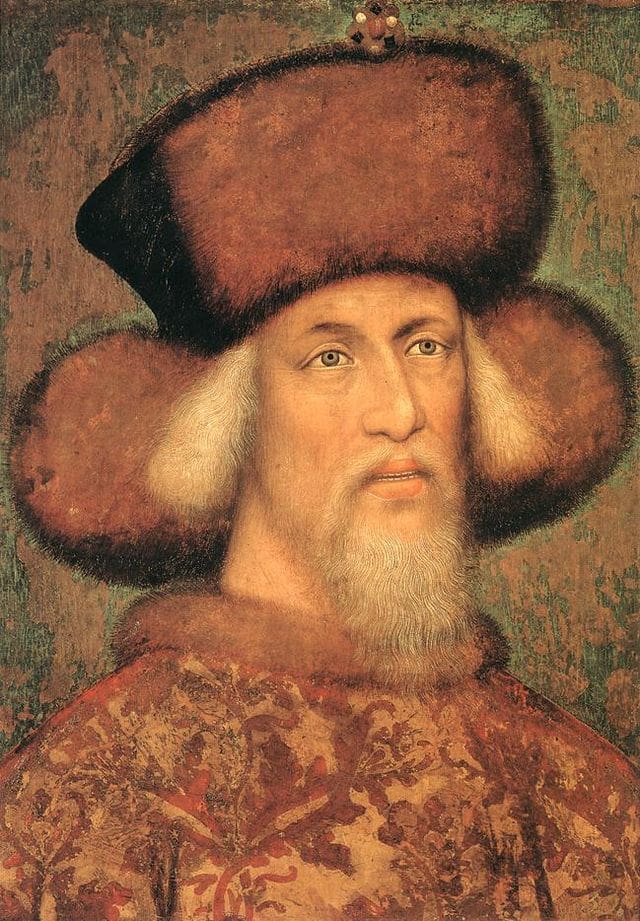

The first secular monarchical order, the Fraternal Society of Saint George, was founded in 1326 by Charles I, also known as Charles Robert, the first Anjou King of the Kingdom of Hungary. Despite the charter and the seal of the order having survived, we know very little about the order’s functioning. Sigismund of Luxembourg, the ruler who ascended the Hungarian throne in 1387 (King of Hungary: 1387–1437; King of Bohemia: 1419–37; King of Germany: 1411–37; Holy Roman Emperor: 1433–37), and whose first wife was the granddaughter of Charles I, could, of course, have heard of his predecessor’s order, and perhaps even followed his example when he himself founded an equestrian order in 1408.[1]

However, the similarities between the two kings’ orders end here. While Charles Robert’s order tried to prescribe an actually ordered community for its members, with a seat, a limited number of members, and strictly laid down joint gatherings, the Order of the Dragon founded by Sigismund in 1408 was the exact opposite. It had no formal patron (though the statutes refer twice to St George and his dragon), no seat with a chapel, no regular meetings, with no references to any chivalrous idea or exercise, perhaps with the exception of the requirement of attending the funerals of any of the members who died. Probably, [Canadian medieval historian and heraldic author] D’Arcy Boulton is right that this Order was the first organisation of its type to be conceived of in purely political terms.[2] There is nothing surprising in this;

Sigismund was a master of political strategy and diplomatic solutions,

and everything he lost on the battlefields he won back many times at the negotiating table. In the beginning he perhaps did have some kind of organised operation in mind, since he initially named judge royal Simon Rozgonyi (1409–1414) as the dean and rector of the Order, but later this title can never be heard of again.

The charter of the Order was jointly issued by King Sigismund and his wife Borbála in 1408.[3] By then, Sigismund had already suffered the greatest military and political defeats of his life: in 1396, the Ottoman Sultan defeated his army at Nicopolis, and then in 1401 he was captured by the lords of the country, and was almost overthrown. However, Sigismund survived both fiascos, and after that he established such a solid power that he did not have to count on any kind of rebellion later on during his multiannual travels in Western Europe, in which the Order of the Dragon certainly played a decisive role. Already in 1408, the list of members included the country’s most important aristocrats, as well as the King’s most significant foreign policy vassals. Given that an unlimited number of domestic and foreign persons could receive the badge of the order, it can undoubtedly be considered an effective tool for early political networking.

The foundation charter in its prologue in general terms summarises the aim of this Order (called Societas Draconica seu Draconistarum) as follows: it was founded ‘with prelates, barons, magnates of our kingdom, whom we invite to participate with us in this party by reason of the sign and effigy of our pure inclination to crush the pernicious deeds of the same perfidious Enemy, and the followers of the ancient Dragon, of the pagan knights, schismatics, and other nations of the Orthodox faith and those of envious of the Cross of Christ and of our kingdoms…’.[4] Consequently, the members had to swear eternal fidelity to the royal couple and their sons as yet unborn (later added also daughters because Sigismund had only a daughter, Elisabeth), and they all had to defend one another against all aggression. In return, the members had several privileges, like the special protection of the King.

The Order consisted of two classes. The composition of the membership genuinely reflected the intention of the charter: the gentry was given a place in the category reserved for non-aristocrats, thanks to which several of them could make a great career, such as the members of the aristocratic Báthory family, among whom, for example, Stephen Báthory later became King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania (r. 1576–1586). The fragment of a stove tile depicting a large number of dragons proves that

the order became widely known in Hungary not only in high society.

The inner circle of the members of the Order was characterised by a certain constancy—in 1423, twenty-two lords affixed their seals to the Polish–Hungarian peace treaty, ten of whom were the same as those in the charter.

The vassal lords of the neighbouring territories, such as the Grand Duke of Bosnia, the Serbian Despot, and the Voivode of Wallachia all became members of the Order, despite the fact that the latter two were Orthodox. Their alliance was also a pillar of King Sigismund’s anti-Ottoman policy, keeping these three principalities in the country’s buffer zone. The most problematic area was Bosnia, where Sigismund had been in a constant armed struggle with Grand Duke Hrvoje since 1387, but he finally managed to defeat him in 1408. The King’s victory directly contributed to the establishment of the Order. In the end, Sigismund had better luck with Serbia: with the death of Despot Stefan Lazarević, a member of the Order, Sigismund could irrevocably acquire the territory of Serbia in 1427. Meanwhile, the Hungarian expansion towards Wallachia was also continuous. In 1431, Vlad II Dracul, the Voivode of Wallachia (r. 1437–1442; 1444–1447), became a member of the Order as well, who, together with his son Vlad III, was referred to as ‘Dracula’ (draco in Latin, ‘dragon’ in English). Their former residences in Hungary have been identified in Pécs (Drakwlyahaza, i.e. The House of Dracula, 1489) and Segesvár (today’s Sighișoara in Transylvania, Romania). Political considerations justified that Sigismund also recruited the Dukes of Padua and Verona, opposing Venice. The badge could also have been accompanied by a certificate, too, as was the case with Vytautas (Witold), Grand Duke of Lithuania (r. 1392–1430).

There were other illustrious international members of the order as well who received membership as an honorary diplomatic gift from the Hungarian King, such as King Henry V of England (1416) and King Erik of Denmark (1419), often with the right to pass on the badge of the order, just like the Albanian national hero Skanderbeg (d. 1468) received the title from King Alfonso V of Aragon. The recruitment of famous German poet Oswald von Wolkenstein to the Order shows that the King also thought about supporting his own media presence.

Despite a large number of donations, it seems that the badge of the order was considered a serious honour by the recipients and was carefully depicted in their coats of arms and on their tombstones. The international nature of the Order of the Dragon was further strengthened in 1433 when the Pope agreed to amend the Order’s regulations during the coronation of Sigismund as Holy Roman Emperor in Rome. It was then that those who fought for the aims of the Order were granted complete forgiveness of their sins as if they were crusaders.

Sigismund himself considered the badge of the order as a symbol of his reign until the end of his life and even engraved it on his seals. The badge had several variants, like simply a dragon, or a dragon suspended or hanging from the cross, with the words ‘O quam misericors est deus, justus et pius’ (‘Oh, how merciful God is, faithful and just’). The badge was worn on the left side hanging on a string. The barons could wear both the dragon and the cross, but the others, whose number was unlimited, were only allowed to wear the dragon. It took the form of a broch of different sizes, made of silver-gilt, or gold fabric sewed to the garment. The combination of the flaming cross with the dragon was a reference to the heavenly cross of Roman Emperor Constantine the Great, and the idea was perhaps already born during the Battle of Nicopolis.

The survival of the Order of the Dragon does not leave any questions unanswered. Sigismund’s daughter Elisabeth became the wife of King Albert I Habsburg (r. 1437–1439), who had already been a member of the Order. Elisabeth herself also passed on the badge: her right to bestow the Order was inherited by her son Ladislaus V Habsburg (r. 1444–1457) and after his death by King Matthias I (r. 1458–1490). At the same time as Ladislaus V, Frederick III of Germany could also practice bestowal, as he considered himself the guardian of the minor King Ladislaus V. Perhaps the Order even survived the death of King Matthias, and during the reign of the Jagiellonian kings from 1490 to 1526, dragons often appeared on their coat of arms as well. Later, however, there was no further reference to the Order; it lost its former importance, in line with the weakening of Hungary’s international position and the Ottoman conquest.

Nevertheless, the memory of the equestrian order lived on intensely in the Central European public consciousness.

In modern times, the Order of the Dragon was founded under the name ‘the Brethren of the Croatian Dragon’ in 1905 in Zagreb as a Croatian fraternal and cultural society. Although the Brotherhood was banned in 1946, it was revived in 1990 in Zagreb.[5] Then, in 2011, Prince Aleksandar Karadjordjevic brought the Order back to life as ‘The Sovereign Military Order of the Dragon’, with a permanent seat in Belgrade. Its patron saint is King Lazar Hrebeljanovic, the Serbian ruler who died in 1389, in the Battle of Kosovo against the Ottomans. An attempt to re-establish the Order was also made in 2001 in Oradea, Romania, the city where King Sigismund was buried.

After the disintegration of the Habsburg Monarchy, the restoration of the honours of independent Hungary was on the agenda again. In 1920, it was seriously considered that the most important award of the new Hungarian State would be linked to the former Order of the Dragon, which, however, has not been attained. In Hungary, the prestige of the Order was inseparable from the assessment of Sigismund’s reign: the King was traditionally seen as a weak, bad king in the country. Later, however, the international exhibitions dedicated to his memory in 1986 and 2006 brought about a turning point in this perception: they once again placed Sigismund among the ranks of the greatest Hungarian rulers of all time, together with his equestrian order, the Order of the Dragon.[6]

[1] Pál Lővei, ‘Monarchical orders in medieval Hungary: the Orders of Saint George and the Dragon’, in Gianina-Diana Legar, Péter Szőcs, et al. (eds.), Evul mediu neterminat. / Studies in honour of professor Adrian Andrei Rusu on his 70th birthday, Cluj-Napoca, 2022, pp. 95–113.

[2] D’Arcy J. D. Boulton, The Knights of the Crown: The Monarchical Orders of Knighthood in Later Medieval Europe 1325–1520,Woodbridge–Rochester, 2000, pp. 350–355.

[3] György Rácz, Pál Lővei, ‘Die Grundungsurkunde des Sankt Georgsordens mit dem Siegel des Ordens’, in Imre Takács (ed.), Sigismundus Rex et Imperator. Kunst und Kultur zur Zeit Sigismunds von Luxemburg, 1387–1437, Mainz, 2006, p. 337.

[4] Translated in Boulton, The Knights of the Crown op. cit. p. 350.

[5] Ivan Mirnik, ‘The Order of the Dragon as reflected in Hungarian and Croatian Heraldry’, Proceedings of the XXVII International Congress of Genealogical and Heraldic Sciences St Andrews, 21–26 August 2006, Vol. 2, Edinburgh, 2008, pp. 563–588.

[6] Pál Lővei, ‘Hoforden im Mittelalter, unter besonderer Berücksichtigung des Drachenordens‘, Sigismundus Rex et Imperator op. cit., p. 251–263.

Related articles: