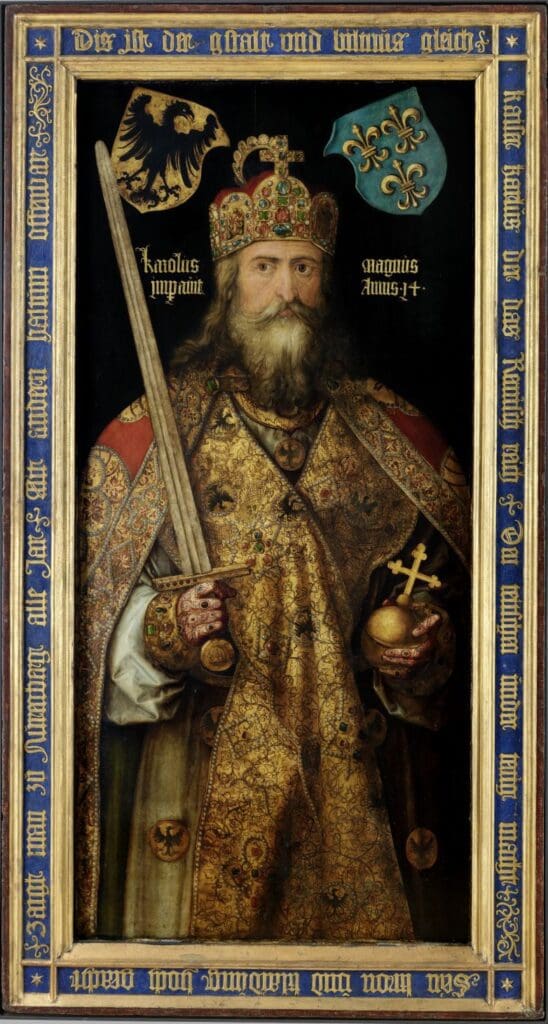

Charles I the Great, or Charlemagne (r. AD 768–814), who was elected Holy Roman Emperor at Christmas 800, has not accidentally been called the ‘Father of Europe’ (Pater Europae) by a contemporary poem. He and his dynasty founded medieval Europe, and it is no coincidence that the International Charlemagne Prize of Aachen has been awarded in Aachen, Germany since 1950, which Pope Francis received in 2016, too. Charlemagne’s figure, as well as the myths and legends associated with him, had a great influence on medieval Western European chronicles and fiction, but medieval Hungarian historiography—similarly to the Central European one—was surprisingly little affected by it. Although a German chronicler of the 12th century failed to find a Hungarian mother for Charles the Great in the person of Frankish Queen Bertrada of Laon, Charles’ name was written down for the first time by Hungarian humanist chroniclers in the 15th century, which corresponded to their efforts to connect Hungarian and universal history as closely as possible. Nevertheless, the relationship between Charlemagne and Hungary is quite exciting.[1]

The legend of Charlemagne may have first influenced the legend of King Saint Ladislaus in Hungary at the end of the 12th century, which is not surprising as Charles the Great’s canonisation, one of the most famous ones of the century, took place in Aachen at the initiative and in the presence of Holy Roman Emperor Frederick Barbarossa. The canonisation of Saint Ladislaus on 27 June 1192 in Oradea also fits in this list, certainly by a papal legate and in the presence of Hungarian King Béla III.[2]

The most important land route to the Holy Land led through Hungary, which may have been a source of the news about Charlemagne. The relationship between Charles the Great and the Holy Land is already reported in contemporary sources from the 9th century, although, in accordance with reality, they are about the sending of ambassadors and gifts. The myth of the pilgrimage taken personally by Charles was formed already before the First Crusade, and then his Spanish campaign in 778 was also reinterpreted in the spirit of the crusader idea and immortalised in the Old French ‘The Song of Roland’. The Spanish stories were then expanded and elaborated, and the image of the Emperor fighting against the Muslims became complete as well. Today, it is difficult to identify whether Charles the Great’s legend, including the ‘The Song of Roland’, could also be read in manuscripts occurring in large numbers in Hungary—it could have been, suggested by the Hungarian names Roland, Lóránt, and Olivér.[3]

At the same time,

it is an indisputable fact that the figure of Charles the Great played an insignificant role in Central European historiography before the 14th century,

while he enjoyed wide popularity in the West.[4] The reason for this may be that the scribes of the region had some difficulty reaching the vernacular Charles–literature, ‘The Song of Roland’, and other similar texts. When writing down the national historical traditions, the attention of these scribes was directed almost exclusively to their own domestic saints: in Hungary to the holy kings such as St Stephen, St Emeric, and St Ladislaus; in Czechia to St Wenceslaus, Duke of Bohemia; and in Poland to St Adalbert and St Stanislaus. In this list, there was obviously no place for Charles the Great.

When scribes were working on The Legend of St Ladislaus at the end of the 12th century, it goes without saying that they turned to the manuscripts about Charles for help. This could have been completely natural as in the introduction to The Legend of Charlemagne, Frederick Barbarossa was called ‘The Second Charlemagne’ (alterum magnum Karolum). King Béla III and Frederick also met in person in 1189, and the first tournament organised on Hungarian soil was connected to this visit, too. However, Philip II of France also took advantage of the myth of Charlemagne: the French chroniclers compared Philip’s victory at Bouvines in 1214 to Charlemagne’s triumph over the Saxons. According to them, before the battle, the French King encouraged his soldiers to follow the example of their ancestors, the Trojans, Charlemagne, and his knights, Roland and Oliver.[5] As this crusading tradition was exploited in France, it is likely that Béla III also wanted to be compared to St Ladislaus and Charles, all the more so since he married Philip II’s sister, Margaret.

The next appearance of Charles the Great in Hungary traces back to the 15th century. According to the world chronicle of John of Udine, after the leaders of Charles defeated the Muslims in Spain in 802, they reached Hungary. After winning a victory here as well, ten thousand of the Saxons were settled in Transylvania and in the Spiš region (now Northern Slovakia), which is no surprise either: from the 12th century onwards, until World War II, several German ethnic districts were established in the country.

The 15th-century Italian chronicler Antonio Bonfini also mentioned the name of the Frankish Emperor countless times in connection with Hungary. In his work, he places the Hungarian conquest of the Carpathian Basin in the time of Charles the Great, for the simple reason that he identifies the Avars with the Hungarians. He believed that the Frankish–Avar wars that started in 791 had given a much more dignified framework to the battles of the Hungarian conquest than the Hungarian historical tradition. In Bonfini’s description, the ‘terrible war’ between the Hungarians and the Franks lasted for eight years, during which the Franks looted the Buda treasury of the ‘Avar’ leader, i.e. the Hungarian King—Charlemagne marched in Buda personally and claimed the royal palace for himself. In this context, Bonfini also mentioned that the Emperor left Germans behind to keep the Hungarians at bay.

Charlemagne’s Pannonian campaign that broke the power of the Avars was indeed well known to his contemporaries, too.

The Frankish King did reach the western border of present-day Hungary with his army, all the way to the Rába River. According to some chroniclers, he also personally made a pilgrimage to the city of Savaria, today’s Szombathely, Hungary, the well-known birthplace of St Martin of Tours.

Bonfini also knew that Charles the Great was the first to introduce Christianity in Pannonia and that St Stephen’s father, Grand Prince Géza, had followed him only as the second Christian missionary of Hungary. In Bonfini’s work, the looting of the treasury of the Avar leader by the Franks appears as the main motive for the Hungarian raids. According to him, the Hungarians, with their marauding raids to the west between 899 and 955, merely attempted to recover the treasures that had been unlawfully taken from them. Other contemporary German chroniclers (such as Person Gobelinus or Dietrich Engelhus) believed that the Transylvanian Germans had been brought and settled by the Hungarians returning from the western raids.

The Pannonian conversion associated with the name of Charlemagne has another, earlier source as well, found in a chest full of precious relics discovered in the Andechs Monastery in Bavaria in 1388. Among the relics was the so-called ‘Victory Cross of Charles the Great’ from the 12th century. According to the records, ‘an angel brought it to King Charles to fight against the infidels (…) Later this cross appeared to Stephen [St Stephen of Hungary], who founded Hungary’s first church at the place of the revelation.’

A surprising memory of the relationship between Charles and Hungary is the 90 cm long sword, more precisely a sabre, attributed to Charlemagne, kept in Vienna today.[6] The sword was one of the German coronation symbols (regalia) kept in Aachen, which then ended up in the imperial treasury in Vienna, together with the imperial crown. Its name can be traced back to the tradition that German Emperor Otto III visited Charlemagne’s tomb in Aachen in 1000, from which he took several relics with him. Since the sword is a curved sabre of the 10th century, presumably of the Carpathian Basin nomadic type, it was certainly not among them. Perhaps the Bavarian prince received the same sword as a gift in the Hungarian court in 1063 as the sword of Attila the Hun. However, the memory of this later faded and it was given to Emperor Ferdinand of Habsburg as Charles’ sword in 1562. When receiving it, Ferdinand exclaimed in surprise, ‘this is a Hungarian sword’!

The centre of the European cult of Charles, of course, remained Aachen,

boasting the relics of the Virgin Mary. We know about the Hungarian pilgrims in Aachen from very early times. In 1357, Queen Elisabeth of Hungary, mother of King Louis I (r. 1342–1382) made a pilgrimage to Aachen with the same Emperor Charles IV, who was also carrying out major construction works in the church in Aachen and boosting Charles’ respect in Central Europe. After the visit, the Hungarian King established a chapel in Aachen where he placed the relics of the Hungarian holy kings, and also provided a Hungarian-speaking priest. The chapel, which still preserves the gifts of Louis the Great, first appeared in historical sources in 1367 and was rebuilt in 1776 by Queen Maria Theresa of Austria in baroque style, with the statues of the Hungarian holy kings in it.[7] The still-existing Hungarian chapel and the artworks preserved there made the spiritual relationship between Charlemagne and Hungary tangible in works of art as well. The strength of the tradition is shown by the fact that after 1956, next to the Mariazell Basilica, Aachen became the most important sacred centre of Hungarian emigrants living in Austria and Germany, which democratic Hungary thanked with a statue of St Stephen inaugurated near the Aachen Cathedral in the presence of former Hungarian Prime Minister József Antall in 1993.

[1] László Veszprémy, ‘Kaiser Karl der Grosse und Ungarn’, in Márta Nagy and László Jónácsik (eds.), ‘Swer sinen vriunt behaltet, daz ist lobelich’. Festschrift für András Vizkelety, Budapest–Piliscsaba, 2001, pp. 195–204.

[2] Gábor Klaniczay, Holy Rulers, Blessed Princesses. Dynastic Cults in Medieval Central Europe, Cambridge, 2002, p. 154.

[3] Szabolcs de Vajay, ‘Rayonnement de la Chanson de Roland. Le couple anthroponyme “Roland et Olivier” en Hongrie médiévale’, Le Moyen Age, Vol. 68, No. 3–4, 1962, pp. 321–329.

[4] Florin Curta and Jace Stuckey, ‘Charlemagne in Medieval East Central Europe (ca. 800 to ca. 1200)’, Canadian Slavonic Papers / Revue Canadienne des Slavistes, Vol. 53, No. 2/4, 2011, pp. 207–208.

[5] Gabrielle M. Spiegel, ‘Political Utility in Medieval Historiography’, History and Theory, Vol. 14, 1975, p. 323.

[6] TaliaZajac, ‘Remembrance and Erasure of Objects Belonging to Rus’ Princesses in Medieval Western Sources: the Cases of Anastasia Iaroslavna’s “Saber of Charlemagne” and Anna Iaroslavna’s Red Gem’, in Tracy Chapman Hamilton and Mariah Proctor-Tiffany (eds.), Moving Women, Moving Objects, 500–1500, Leiden, 2019, pp. 38–46.

[7] Frank Pohle, ‘Die Ungarische Kapelle des Aachener Münster in der Gegenreformation’, Ungarn–Jahrbuch, Vol. 28, 2007, pp. 377–392.