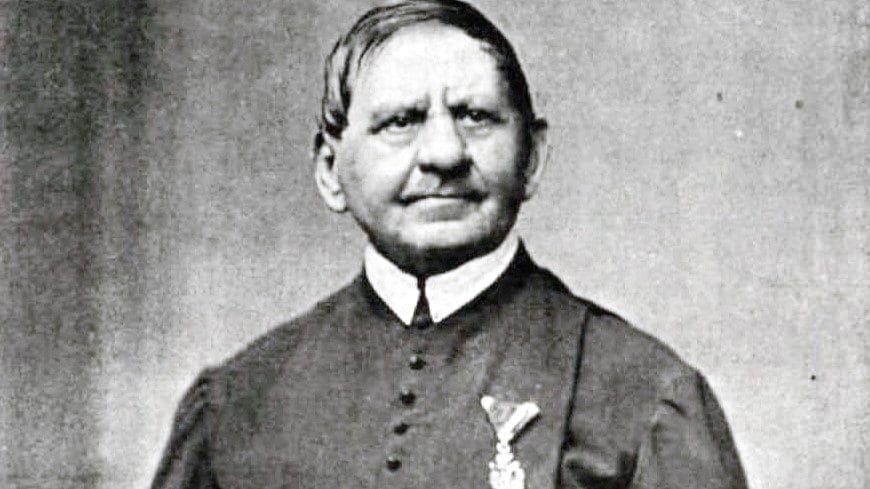

Ányos István Jedlik was a remarkable Hungarian polymath. His versatility extended across multiple disciplines, encompassing such roles as an inventor, engineer, and a scientist in the realm of physics, while he also worked as a teacher. His great intellect led him to many great scientific achievements, among which are the invention of soda water-making in Hungary,

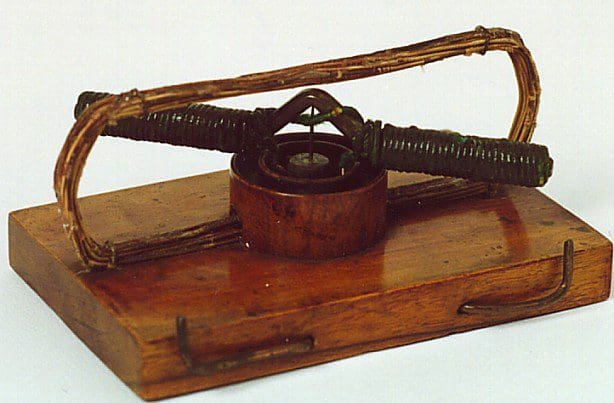

the discovery of the dynamo principle,

the building of the first electric motor and numerous others. Moreover, he also authored a vast bibliography of works, including one of his most noteworthy contributions to the field of science, the Elements of Natural Science (Természettan elemei). But apart from being a scientist, he was first and foremost a priest of the Benedictine order, hence his second name, Ányos (Anian). The life and work of the Hungarian polymath is a prime example how deep religious faith can harmoniously coexist with scientific endeavour.

His exceptional intellectual capabilities became evident from a very young age. With the selfless sacrifice of his parents, who, although simple farmers, recognized the importance of education, he was able to attend the best institutions of the time. Born in the provincial town of Szímő (today Zemné, Slovakia), he was sent to study at the prestigious university of Nagyszombat (today, Trnava ins Slovakia) and later to Pozsony (Bratislava). At the age of 17, he entered the Benedictine order in Pannonhalma.

Else then a faithful Catholic and an exceptional scientist, Jedlik was also an ardent patriot. Even prior to the enactment of the law that established the Hungarian language as the language of public education, he extensively used Hungarian during his lectures, and Hungarian technical terms in his scientific work, enriching the Hungarian language with a new scientific vocabulary. Before 1844, the language of education was Latin, which Jedlik, being a scientist, mastered, along with German, Hungarian and Slovak. But

he was tireless in his efforts to make Hungarian more suitable for expressing scientific ideas,

and therefore, the modern Hungarian scientific community owes him for introducing essential terms such as dugattyú (piston), huzal (wire), nyomaték (torque), térfogat (volume), halmazállapot (state of matter), among others, which continue to be used to this day by Hungarian scientists, engineers and the everyman alike.

His deep love for his country also compelled him join the ranks of the Hungarian National Guard during the 1848–1849 revolution. He dug trenches, stood on sentry duty, erected fortifications, and provided any other assistance he could during the freedom fight for Hungary’s sovereignty. He also had a major role in protecting scientific institutions during the war. During the notorious bombardment of Pest by the forces of the Austrian general Heinrich Hentzi, Jedlik managed to save the instruments of the Royal Pest University’s (today known as Eötvös Loránd University) natural science room. According to some historic records, Jedlik displayed remarkable determination in saving the instruments from the dangers of the bombardment, and despite the challenging circumstances of the incessant shelling, succeeded in relocating the tools to the basement and other secure areas within the university building.

Jedlik’s achievements in the sciences were recognized in Hungary in his lifetime. In 1858, he earned the distinction of acquiring the full membership of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, bypassing the usual step of first becoming its external member.

In 1863, he was appointed rector of the Royal Pest University.

In recognition of his contributions, he was bestowed with the prestigious title of royal councillor and was awarded the Order of the Iron Crown. In 1878, Jedlik requested his retirement, and as a result, the professorship of the 78-year-old scientist was taken over by 30-year-old Loránd Eötvös, whom the university was subsequently named after. Following his retirement, he spent his final years in Győr.

Even though he had dedicated all his life to science, he never ceased to be faithful to God and patriotic to his country. The combination of all these traits was best summarized by Loránd Eötvös in his remarks at Jedlik’s funeral. This is how Eötvös eulogized his great predecessor:

‘The unshakable faith in God, the love of science, the never-failing diligence of the teacher, the kind heart sympathetic to the plight of his fellow men, the selfless patriotism, are all traits that started to develop and strengthened in Jedlik’s character as he followed the traditional customs of his order.’

The life of Jedlik demonstrates that even in the era of scientific progress, there is room for a harmonious, holistic worldview that encompasses the commitment to the scientific method, a deep feeling of national belonging, and faith as a guiding light.