‘Echoes from the Balcony: Media and Culture During the Ceaușescu Regime’, the first part of this series showed how Ceaușescu harnessed media and culture, and the institutional machinery through which he exercised near-total control over this sphere of social life. Media was not a secondary instrument, but a structural pillar of his personal dictatorship built inside a Stalinist dictatorship. This second part descends to the micro level, presenting how the institutional philosophy of the regime manifested itself on a local level.

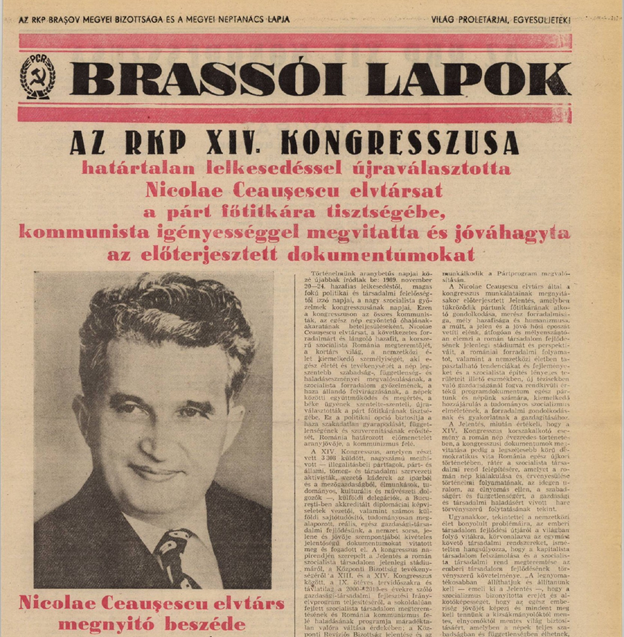

At the centre of this inquiry is a little-known interview series, Itthon, e hazában (At Home, in This Homeland), written by Szenyei Sándor and published in Brassói Lapok (The Brașov Papers) during the twilight years of the 1980s. This choice would seem intuitive in some aspects and contraintiutive in others. On the first hand, Brașov was the epicentre of socialist modernization in Romania. It industrialized before 1945 and by the 80s had a large population of industrial workers and huge factories in heavy industry.

On the other hand, Brassói Lapok was the weekly newspaper of the local Hungarian minority, who lived in nearby villages or in the city. The Hungarian minority in the city and in the county as a whole was around 10 per cent—a relatively small community compared to the dominant Romanian majority. Nonetheless, even if we consider this minority as a semi-clandestine subculture within Brașov, one of their main cultural products—Brassói Lapok—closely mirrored and reproduced the ideological patterns imposed by the regime’s totalitarian institutions.

The interviews can be read on two levels. On the surface, they reproduce the regime’s ideal type of man: the ‘model socialist worker’, a figure embodying discipline, loyalty, and self-improvement. Yet beneath this formula, fragments of lived reality emerge—circumstances, outlooks, identities. In this sense, the texts open a window onto the ethnic and social dynamics of Brașov’s Hungarian community.

Their peculiar value lies in this duality: while they presented recognizable local personalities—people known in their circles—they also suggested that these could have been anyone’s stories.

The Role of Brassói Lapok in the Hungarian Community of Brașov

When Brassói Lapok first appeared in 1895, it was little more than a local bulletin for the Hungarians of the Burzenland and the surrounding villages. However, after the border changes of 1918, Brassói Lapok became a crucial forum for minority politics, and by the interwar years—when industrialization was rapidly transforming Brașov—it had risen to national prominence. Its editors engaged not only in literary and political debates but also in the pressing social dilemmas of Transylvania’s Hungarians.

Writers such as Sándor Márai, János Bartalis, and Elek Benedek appeared in its pages, while the paper also carried interviews with international figures such as Thomas Mann and Josephine Baker. By the 1930s, under the editorial leadership of two intellectuals of the era, Sándor Kacsó and Bertalan Füzi, the newspaper had taken a marked leftward turn, carving out space for anti-fascist voices, populist writers, and sympathizers of the labour movement.

In 1940 the newspaper was banned but was revived as Új Idők (New Times) in 1963. It reappeared under its historic name in 1969, this time with the backing of the Romanian Communist Party. By then, of course, editorial independence was unthinkable. Like every other outlet in socialist Romania, Brassói Lapok operated under Party supervision, its editors subject to censorship and ideological oversight. Even so, the newspaper managed—at least in part—to meet the needs of the Hungarian community, offering a platform for shared concerns and a semblance of cultural identity.

One indication of this role is that, when Ceaușescu’s reign came to an end in 1989, Brassói Lapok was among the few newspapers that did not change its name. In the collective memory of the community, it was not considered fully compromised by the regime.

‘The editors followed Party directives with unquestioning discipline…Yet the paper never became entirely hollow’

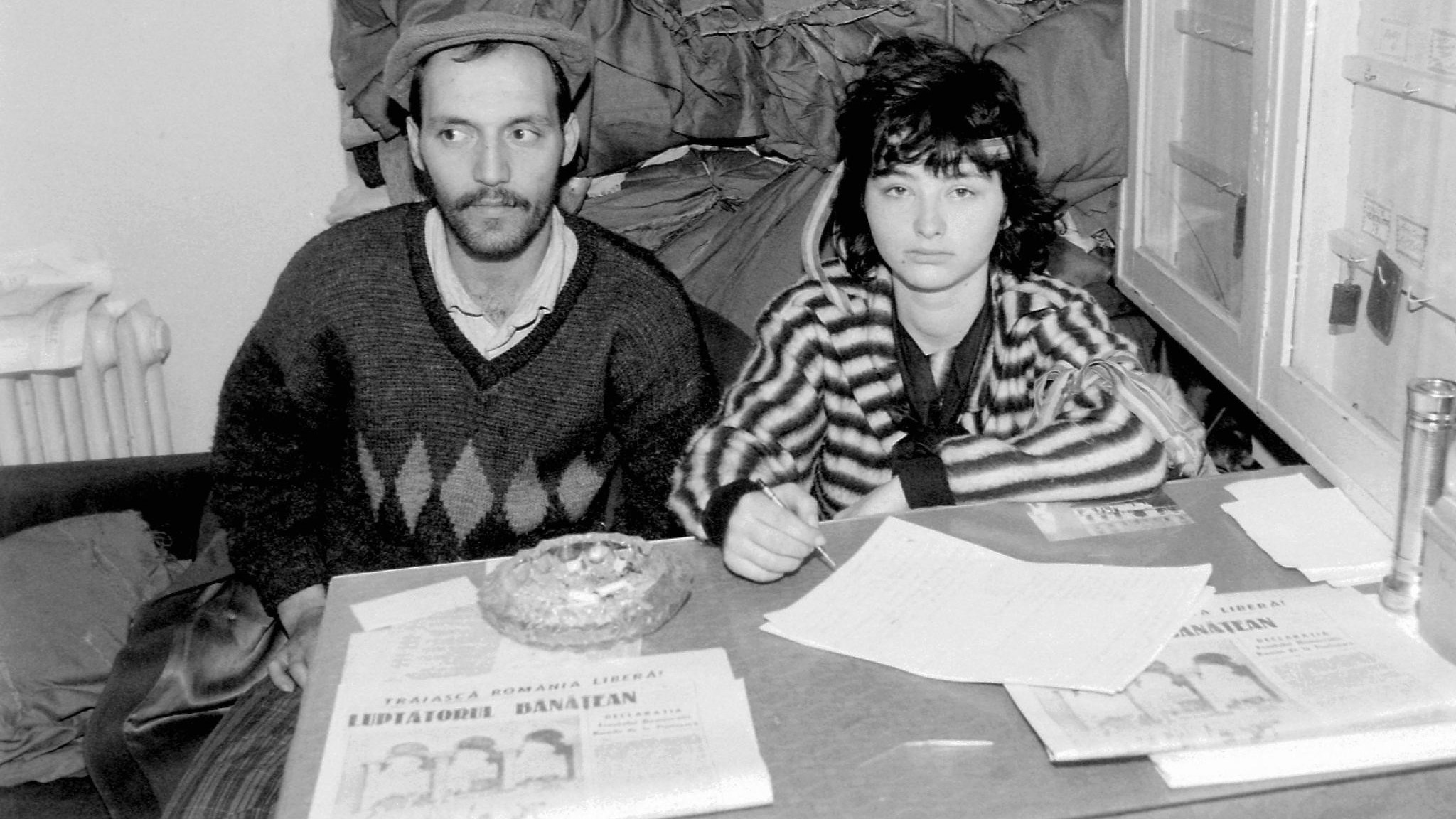

Of course, the reality is more complex—but that is precisely what makes Brassói Lapok so revealing. The editors followed Party directives with unquestioning discipline, and the Securitate maintained a constant presence around the newsroom. Yet the paper never became entirely hollow. It continued to publish local stories, cultural notes, and human-interest pieces that resonated with its Hungarian readership—enough to sustain the sense that this was still their newspaper, even if heavily constrained.

Sándor Szenyei as Journalist

Born in Torda in 1934, Sándor Szenyei rose to become one of the important figures of Hungarian-language journalism in Romania during the last decades of socialism. After studies in Cluj (Kolozsvár) and Bucharest (București), he launched his career by winning a reporting contest at the daily Truth (Igazság). In 1970 he joined the editorial staff of the Brassói Lapok and remained there until his retirement two decades later. Alongside his newsroom work, he published volumes of reportage and produced widely read series that sought to capture the rhythms of rural life—vivid sketches that translated the abstractions of ‘socialist modernization’ into tangible human stories.

One of the curiosities of his career was his penchant for pseudonyms. Readers encountered him under several guises—Patai Sándor, Tordai Sándor, Szamosi Barna—each signalling a different mode of writing. As Szamosi Barna he covered sport; as Patai Sándor he produced social reportage. The masquerade was playful but never hidden. In the final issue of Brassói Lapok in 1984, when the editorial staff offered holiday greetings to readers, Szenyei himself disclosed the ruse with a mixture of irony and humility:

‘Not to mislead the reader, but I would like Szenyei Sándor, Tordai Sándor, Patai Sándor, and Szamosi Barna to write better articles in 1985 than they did this year—for these four names all hide the same journalist. And by “better,” I mean as judged not by myself but by the reader, who would tell me so in a letter, face to face, or perhaps with a brief, warm message such as: “I have placed your latest article in a frame on my wall alongside the others! My full admiration is yours—keep it up!” That is what I would like. And my motto remains: everything for the reader!’[1]

The first of these alter egos, Sándor Patai, appeared in the 18th issue of the 1982 volume of Brassói Lapok, and under this name Szenyei would later publish his series Itthon, e hazában. The multiplication of pseudonyms was not, as one might suspect, an effort to evade the censor. Szenyei’s own name appeared openly in the newspaper, and his position itself presupposed Party approval. Rather, the adoption of multiple by-lines was a kind of self-branding and artistic freedom.

Itthon, e hazában as an Interview Series

Among Szenyei’s many contributions to the Brassói Lapok, few were as emblematic as the series Itthon, e hazában. Beginning in 1988, it appeared with near-weekly regularity, a rhythm that itself signalled the importance the paper attached to it. The ambition was straightforward but far from trivial: to capture the fabric of local life—how people lived and worked, how they navigated the demands of late socialism. To do so, Szenyei frequently left the newsroom behind, traveling into the surrounding villages and small towns, returning with portraits of their inhabitants, their routines, their habits.

A note of caution is necessary. The press in socialist Romania functioned under strict political control. Interviewees could not voice anything that contradicted the official line, and in some cases the newsroom itself may have reshaped material to meet ideological expectations. Yet wholesale fabrication was unlikely. Many of the individuals featured were well known in Brașov’s Hungarian community, and transparent distortions would have quickly undermined the series, reducing it to farce.

‘Each life story…presented two portraits at once: the “model socialist worker”, loyal and industrious, and the individual behind the mask’

On the surface, the interviews followed a simple structure. Each text ran five to seven hundred words and began with a short preface situating the encounter—usually at the subject’s workplace or home—before sketching a few personal traits. These traits were never neutral; they were aligned with professional function and meant to illustrate exemplary devotion. One subject, Pál Liszka, economic secretary of the aeronautics company’s Party committee, was presented as someone who ‘darts about’[2] at his workplace—an image designed not merely to convey busyness but to embody socialist commitment in motion.

Each life story thus presented two portraits at once: the ‘model socialist worker’, loyal and industrious, and the individual behind the mask, with his or her own dilemmas and aspirations. Interviewees often hinted at this duality—the tension between collective expectations and personal desires—even if rarely in explicit terms. Professional advancement, self-education, constant learning, and diligence were framed not only as means to success but as values in themselves, internalized as ends worth pursuing.

The moral lesson was unmistakable. Work, commitment, and community service were cast not as sources of material gain but as existential values. For the reader, the implication was clear: social advancement depended on self-improvement, loyalty to the collective, and openness to new technologies and forms of knowledge.

The life stories were anchored in social spaces that symbolized the triumph of socialist modernization—family background, schooling, the workplace. By emphasizing the personal and the particular, the texts translated socialist modernization from abstract slogan into lived and relatable reality. Often, too, they highlighted cultural engagement—amateur theatre, music, sports, artistic expression—complicating the portraits further and broadening the social roles and motivations of the individuals on display.

‘The moral lesson was unmistakable. Work, commitment, and community service were cast not as sources of material gain but as existential values’

On the other hand, both journalist and subjects belonged to Brașov’s relatively small Hungarian community, where nearly everyone knew one another by face or reputation. Even today, defining what it means to be Hungarian in Brașov is difficult; in the 1980s, when the Romanian state denied the very existence of minorities, it was even more ambiguous.

In practice this identity constituted of having connections with certain institutions: Hungarian-language classes, cultural associations, and the intellectual and social networks such as The Brassói Lapok. Churches also played a role, though religious life could not be presented publicly in a positive light, especially by the media. Indirectly, the interviews also revealed that many of the subjects were prominent figure leaders or role models within their community, known to readers and chosen precisely for those qualities.

Taken together, the series offers a vivid snapshot of Brașov’s Hungarian community in the late socialist years: who its leaders were, what achievements distinguished them, and what traits made them admired. Yet one thing is conspicuously absent: the explicit acknowledgment that a Hungarian community existed at all. Such recognition would have contradicted the Party line. Villages appeared only under their Romanian names, even though in everyday speech no one would have used them. The terms ‘Hungarian’ or ‘Hungarian minority’ never surfaced in print. What emerged instead was a coded reality, in which familiar faces, schools, and cultural associations stood in for the community that could not be named.

And here lies the paradox and the value of the series. Even under conditions of strict political control, when every published word carried the imprint of censorship, Itthon, e hazában managed to function as a space of quasi-freedom. By portraying the lives of individuals who were clearly members of a minority that officially ‘did not exist’, the series simultaneously fulfilled the regime’s ideological demands and quietly subverted them.

[1] Brassói Lapok, 1984, Vol. 16, No. 52, p. 6.

[2] Brassói Lapok, 1989, Vol. 21, No. 15, p. 8.

Related articles: