This year, Hungary celebrated the 800th anniversary of the famous Golden Bull, the Hungarian Magna Carta, issued by Hungarian King Andrew II in Székesfehérvár in April 1222. The legal document had a major influence on the development of the Hungarian constitution in later eras. Among its many provisions, the very first article stipulated that a national assembly should be held every year to discuss the legal complaints of the nobles and that it should be held in Székesfehérvár on the feast of King St Stephen:

‘That we are bound to celebrate the feast of Saint Stephen annually in Székesfehérvár unless we should be beset by some urgent matter or prevented by illness. And if we cannot be present, the palatine will definitely be there for us, and shall hear cases in our place, and all the servientes[1] who wish shall freely assemble there.’[2]

This provision can rightly be regarded as one of the first steps on the road to national assemblies, even if there had been older traditions, too. The custom of annual courts of justice may have been alive from the end of the 11th century; they were held between the day of King Stephen’s death, the feast of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary, and the day of the King’s canonization, 20 August. However, these were not, of course, considered to be assemblies in the medieval sense.

Before 1945, many people believed that a late 9th-century assembly in the village of Pusztaszer recorded in Latin chronicles from around 1200 could be considered a pre-modern diet,

a shining testimony to the Hungarians’ sense of justice and cultural superiority.

Today, however, there is no doubt that Pusztaszer is only a fiction of lawyers educated at Western European universities. But, significantly, Hungarian chroniclers around 1200 saw the country’s inhabitants as having chosen their first lords, the ancestors of their kings, of their own free will. In doing so, they gave up their rights in their favour, but they retained a certain degree of constitutional control, which they could exercise in the assemblies.[3]

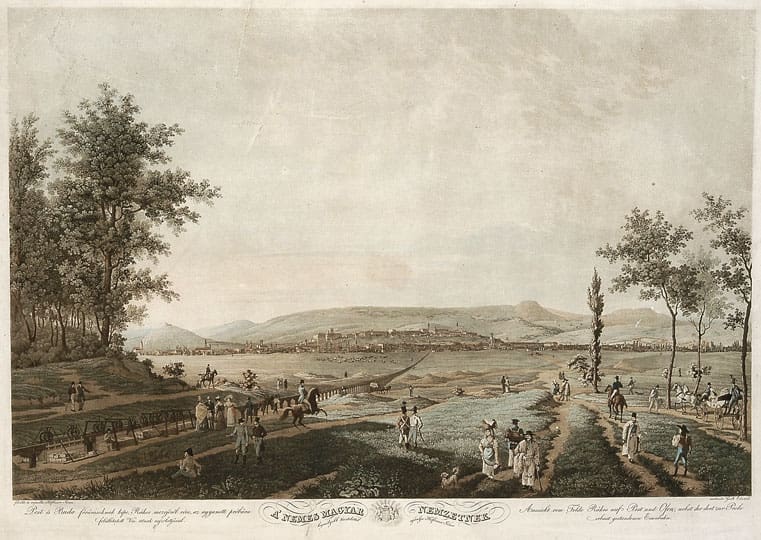

A few decades after 1222, the assemblies were held in Buda, more precisely on the outskirts of the city of Pest, opposite Buda, on the banks of the Rákos stream. The choice of the location of the assemblies reflected the advancement of Óbuda–Buda–Pest in the hierarchy of Hungarian cities. It was until the fall of the medieval Hungarian State that the field of Rákos remained the definitive, if not exclusive, site of the national assemblies. In later times, the phrase ‘going to Rákos’ came to mean ‘going to the Diet’.[4]

The series of assemblies in Rákos began in May 1277 with a meeting called by King Ladislaus IV. In the 1290s, under the last king of the Árpád dynasty, King Andrew III, the beginning of the establishment of the system of noblemen’s estates could already be observed; the words ‘parliament’ and ‘status’ appeared in the Hungarian political language at an unprecedentedly early age.

For historical geographical reasons, it is obvious that Buda and Pest had considerable advantages over Székesfehérvár. Even though the memory of the Székesfehérvár assemblies is still mentioned later, in 1298 the law was passed in the plain of Pest for the second time as well, certainly not far from the city walls and the Franciscan monastery in Pest. The lords lived and held their councils in Buda, and they went over to Pest from there, while the nobility lived in houses and tents in the area of today’s Kerepesi Road. ‘The Diet itself assembled in some sort of fenced compound that was patrolled by armed horsemen, with only two gateways providing access…Here, a wooden stage was set up, “as in a theatre”, on which the king and members of the royal council gathered.’[5]

In the following decades, a large number of assemblies were held, half a hundred by 1440, but most of them had only indirect traces in the sources. However, these assemblies can still be regarded as assemblies even if they did not pass laws. At any time, the king ‘could, within the limits of his own power, listen to and indicate to his subjects his need of their advice and assistance on certain questions’.[6] Nevertheless, when decisions were taken, they were not promulgated as laws, and the texts were lost as well.

The collapse of royal power after the death of King Matthias led to the classic period of the assemblies in the field of Rákos.

In the 36 years after 1490, the Hungarian estates met nearly 50 times. A notable and history-shaping resolution was passed in 1505: in the so-called Resolution at Rákos, drafted by the famous lawyer István Verbőczy, it was agreed that if the king did not have a male heir, only a ruler of Hungarian origin could be elected. This partly resulted in a double election of a king following the defeat at the battle of Mohács, with the appointment of a national king, John Szapolyai (r. 1526–1540), as opposed to Ferdinand I of Habsburg (r. 1526–1564).

In the 1500s, not very uplifting events often took place during the time of the assemblies. The impressionable minor noblemen and the gentry, who usually appeared in large crowds, did not shy away from violence, so in February 1519 they had to be dispersed with arms as they attacked the Buda Castle.

As in all aspects of life in the Middle Ages, the common law provided a reassuring and predictable order in the daily life of the diets. They could be called only by the king, and in his absence by the palatine. Early on, the practice was established that only the high priests and barons received a letter of invitation by name, while the counties and towns were invited as bodies. From 1494 on, the invitation sent out 40 to 30 days before the assembly sought to state the purpose of the assembly, the main items on the agenda, and where and when it would be held. The frequency varied, however, from once a year to every two or three years, until a periodicity of three years was established in the 16th century. Its date was most often Pentecost, St George’s Day, or St Michael’s Day. Due to the high cost of participation, however, it was stipulated after 1492 that the event should begin on the fourth day after the announced date at the latest and be completed within 15 days, but not later than 30 days.

The number of people attending depended largely on whether they came in person or were represented by someone else.

The emergence of representation at diets was at the same time a keyword in modern development,

which mixed and wrestled with the practice of personal attendance for centuries. In 1290, for example, the attendants appeared personally, and after 1490, the same form was adopted. In this form, a keynote speaker was also elected and, if necessary, 120–150 representatives. In addition to the representatives, anyone had the right to participate, since the right to freedom of speech and the right to jurisdiction could not be curtailed. It was understood that the outlying regions, Transylvania, Croatia, Slavonia, and the Seafront were represented as well. In the early centuries, the language of the proceedings was clearly Hungarian—only the final decisions were translated into Latin.

Attendance was not only a right, but also a duty—failure to do so was punished with severe penalties, and only a legitimate excuse was accepted to skip it. During assemblies, jurisdiction was suspended, and participants were given a pass and were free to move about. In the royal council, the nobles met separately, which was later the bud of the two emerging tables (houses). Besides, it also had an important preparatory role: first, the king discussed the agenda with the royal council, the royal proposals were formulated, and only then did negotiations and political bargaining with the estates begin. The assemblies were basically responsible for legislation; emergency war taxes (from 1504 onwards, usually a tax referendum); the election of the king, the palatine, and the crown guards; the highest level of justice (cases involving high treason); finance; and matters concerning the territorial integrity of the country. The powers of the nobility were gradually extended: they were increasingly able to control the use of the royal revenues, appoint a controller to the royal treasurer, and prosecute those suspected of misuse. It is true that by 1500 the gentry had outgrown themselves, but the diet they already ruled did not have the executive apparatus that the king would normally have had.

The message of the Rákos assembly, however, was not clear even to contemporaries. In the Polish language, for instance, ‘Rákos’ has taken on a distinctly negative connotation, meaning ‘a confused, armed gathering’.

Nevertheless, in the Hungarian memory, the Rákos assemblies became a symbol of the freedom of the Hungarian nobility.

The diets in Rákos, as well as the assemblies held in Pressburg (today’s Bratislava, Slovakia) after 1540, played no small role in ensuring that the unity of the country did not disappear after the Turkish rule and that the occupied parts of the country did not entirely break away from the Kingdom either.

The ‘field of Rákos’ and the Resolution at Rákos in 1505 were well known to the Hungarian educated classes before the Second World War. After 1945, however, the memory of the National Assemblies also ‘went down the drain’ as the continuity of Hungarian history was questioned. The problem is more complicated than that, of course. The question is, is there any continuity between the people’s parliamentary assemblies, which were known to have been established in Hungary after 1848, at the beginning of the modern era, and their medieval antecedents? The answer can only be that there is. The medieval Hungarian Kingdom is a historical organic precursor of modern Hungarian democracy, even if it cannot be considered a direct forerunner.

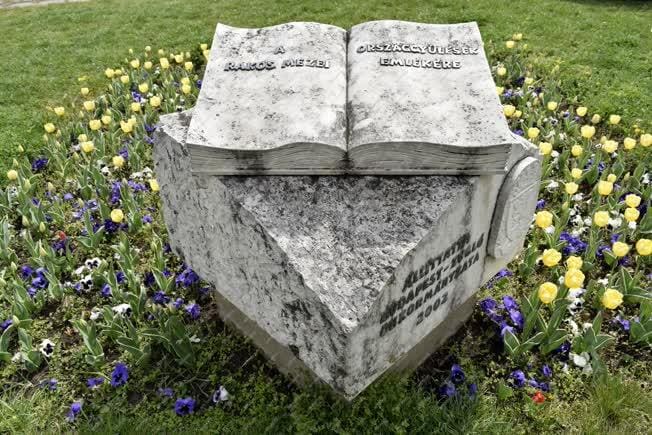

Although there had been talk of commemorating the field of Rákos with a memorial pillar since the mid-19th century, the local government only marked the site with a memorial stone in 2002, and the nearby Királydomb (Royal Hill) was declared a national memorial site by the National Assembly in 2020.

[1] Later used to refer to the nobility.

[2] Online Decreta Regni Mediaevalis Hungariae. The Laws of the Medieval Kingdom of Hungary, János M. Bak (ed.), https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1003&context=lib_mono, accessed 1 December 2023.

[3] László Veszprémy, ‘Mythical Origins of the Hungarian Legislation’, Parliaments, Estates and Representation, Vol. 15, 1995, pp. 67–72.

[4] Ferenc Hörcher and Thomas Lorman (eds.), A History of the Hungarian Constitution: Law, Government and Political Culture in Central Europe, London–New York, 2018, pp. 6–9; 29–45.

[5] Martyn Rady, ‘Law and the Ancient Constitution in Medieval and Early Modern Hungary’, in Ferenc Hörcher and Thomas Lorman (eds.), A History of the Hungarian Constitution, p. 36.

[6] Norbert C. Tóth, ‘A “korai rendiség” és a “rendi állam” között — Országgyűlések 1301–1440 között. Vázlat’, in Tamás Dobszay, H. István Németh et al. (eds.), Rendi országgyűlés — polgári parlament. Érdekképviselet és törvényhozás Magyarországon a 15. századtól 1918-ig, Budapest, 2020, pp. 9–24.

Related articles: