On 7 November at the Szent-Györgyi Albert Agóra in Szeged, the second volume of the book series Hungarian Roots and American Dreams, edited by Réka Bakos and Dr. Anna Fenyvesi, was presented under the title ‘Tracing Personal and Local History’. Following presentations delivered by the editors and Balázs Balogh, four authors shared their own family stories, and finally, we heard about the next five planned volumes as well.

The event was opened by a welcoming speech from Deputy State Secretary for National Policy Péter Szilágyi, who praised the book series, noting that its common thread is that the immigrants appearing in the books left Hungary due to external circumstances. As he mentioned, outside the 10-million-strong mother country, 2.5 million Hungarians live elsewhere within the Carpathian Basin, and another 2.5 million around the world in the diaspora—a unique situation that makes Hungarians a world nation, and one of its consequences is that more and more Hungarians—including many young people—are becoming interested in genealogy and ancestry research.

The books primarily focus on the U.S. and represent a ‘beautiful and high-quality imprint’ of the Hungarian diaspora there, he stated, adding that the project could be continued to include Hungarians living on other continents, and these works should reach every Hungarian community. His favorite story was about Hungarians from Pennsylvania who settled in the now-defunct towns of Balaton, Tokaj, and Nyitra in Georgia. They established a common cemetery, which was recently purchased by a local Hungarian organization and, with the support of the Hungarian state, was restored in recent years, so that the immigrant Hungarian ancestors could rest in a dignified place, in the Budapest Cemetery.

After the enthusiastic opening speech, the editors shared their personal connections to the topic and the books. Réka Bakos revealed that while doing genealogical research, she realized she couldn’t associate her ancestors’ life stories with their birth and death records. When she found her great-grandmother’s ship’s passenger list online, she wanted to learn more about how her great-grandparents lived in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. She wrote about them in one of the volumes and, since part of the family remained abroad, she strives to strengthen family ties with them. Thus, the stories do not end with being written—life keeps writing them, she emphasized. Historian Dr. Anna Fenyvesi has no relatives who immigrated, but in the 1990s, she wrote her PhD in Pittsburgh, PA, where she got to know the local Hungarian communities. Last year, as a Fulbright scholar in Morgantown, West Virginia, she visited Himlerville in eastern Kentucky—the only exclusively Hungarian mining settlement—and wrote the story of one of the families there.

Balázs Balogh, Director General of the ELTE Research Center for the Humanities (Eötvös Loránd University) and Director of its Institute of Ethnology and Cultural Studies, began by also sharing his personal connection: his paternal grandparents’ siblings had immigrated to America. He then delivered a fascinating, image-rich presentation about the Hungarians who immigrated in the five decades preceding World War I. At that time, most immigrants came from northeastern Hungary—from the poorest social classes, typically landless or smallholding peasants—who went abroad for a few years. 90 per cent of them worked in the northeastern quarter of the country. One third eventually returned home, but many remained in America when World War I broke out. Their living environments could generally be classified into three types of settlements: those who arrived in the 1880s established Hungarian colonies in coal mining regions; those who came in the 1890s settled in smaller industrial towns; and those who immigrated in the early 1900s settled in the large cities of heavy industries, and both of these latter waves created ‘Little Hungary’ neighborhoods.

Due to the terrible working conditions and frequent mining accidents, more than 50,000 miners—among them several thousand Hungarians—lost their lives during these decades. In the worst mining disaster of 1907 alone, 134 people perished. The first and most important forum for self-organization was established in 1886—the predecessor of the William Penn Association, called the Verhovay Aid Association. In 1922, the Bethlen Home in Ligonier was founded, initially as an orphanage and later as a nursing home. Today, it operates as a modern healthcare center. Although it has recently lost its Hungarian ownership and character, the museum within its main building still preserves material relics of local Hungarian communities.

Illustrated with historical photographs, he shared with us stories of the various Hungarian settlements—e.g., Dayton, OH, Buckeye Street in Cleveland, OH, the Birmingham neighborhood in Toledo, OH, the Delray district of Detroit, IL, and Pittsburgh, PA—and depicted the apocalyptic landscapes of steelworks and foundries, as well as the burdosház (a Hungarianized form of ‘boarding house’) some examples of which still stand today. The contents of one such building were even transported to the Szentendre Open-Air Ethnographic Museum. He also spoke about how, as job opportunities vanished and other immigrant groups moved into these Hungarian neighborhoods, the descendants of Hungarians scattered far and wide today, and how difficult it is to maintain their Hungarian identity.

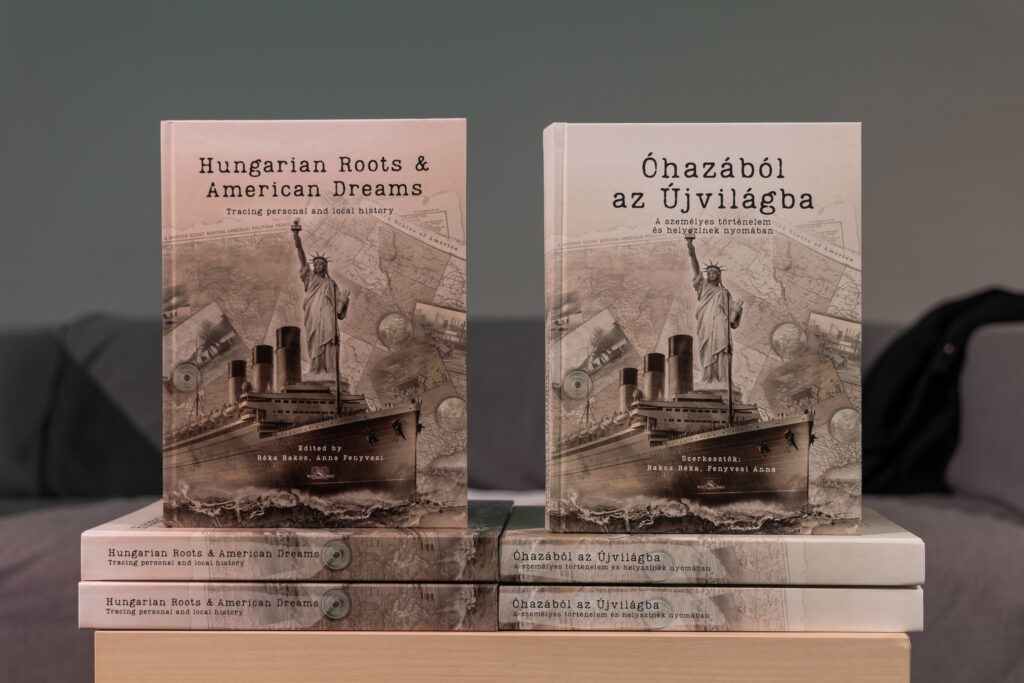

After the presentation, Réka Bakos explained that the starting point of the book series was a social media group called Hungarian Roots and American Dreams, which she co-founded with genealogist János Szabon. The group soon grew to include hundreds of members from around the world. Their primary goal was to preserve memories, but soon many material relics also surfaced, and thanks to the helpfulness of the group members, joint family research projects began. Eventually, on the suggestion of Dr. Anna Fenyvesi, these family chronicles were compiled into written form, 106 of which were included in the first two volumes. While the first volume presented the historical waves of immigration in chronological order, the second volume places them into a geographical context: it presents about 30 major Hungarian locations in the U.S. alongside the 58 personal stories. As a result, the second volume paints a deeper, more colorful, and geographically more diverse picture of Hungarian life in America.

Dr. Anna Fenyvesi listed other recent works with similar themes—the Memory Project, consisting of video interviews created ten years ago by Andrea Lauer Rice and Réka Pigniczky; the Being Hungarian in America interview book series by Ildikó Antal-Ferencz; and the Visszidensek interview book series by Péter Gyuricza. She also emphasized that their contributors include not only Hungarian but also American authors, offering two perspectives on the stories. Their books cover the entire history of Hungarian immigration; instead of scholars, family members themselves are the authors; these are stories of simple, everyday people and include both permanent immigrants and returnees. The American launch of the second volume took place on October 15, 2025, at the Hungarian House in New York City, where four authors introduced their stories, and on October 17, at the Embassy of Hungary to the U.S in Washington, D.C., where three more authors were introduced to the audience.

‘Instead of scholars, family members themselves are the authors; these are stories of simple, everyday people and include both permanent immigrants and returnees’

As a next step, four authors shared their own family stories. Éva Szabóné Rácz herself had lived abroad for several years (in England) before returning to Hungary ten years ago. She began researching the story of her great-great-grandfather, who twice went to work in the coal mines of Detroit, MI, remained there during the war, and eventually returned home. The families of several men who had immigrated under similar circumstances, upon their return to Hungary, collectively purchased a former baronial estate and founded a fairy-tale village where they engaged in agriculture, establishing a school and even a library for their children. After World War II, however, communist nationalization destroyed the so-called Dollar Farm (Dollártanya), and the majority of its 200 residents—including her great-grandparents—left the area.

Mária Bakti told the story of her great-great-grandfather, who emigrated to the U.S. in 1911 and worked there as a well-paid interpreter. He returned to Hungary in 1913 but, leaving behind his wife and young son, who didn’t want to join him, soon emigrated again and started a new family in America. In 1963—after 50 years—he surprised his prior Hungarian family by visiting home. In the 70s and 80s, his American grandson made efforts to strengthen ties with the Hungarian side of the family.

Márk László-Herbert, born to Transylvanian Saxon and Hungarian parents, presented the American story from his mother’s side: his great-grandparents emigrated to America in 1912 as newlyweds, where the husband worked as a researcher and later as a manager in the world’s largest yeast factory. In 1920, they returned to Europe; after World War II, his grandfather was taken to forced labor by the Soviets, while his grandmother lost her American citizenship due to the 1941 U.S. law that revoked citizenship from those who had acquired foreign nationality—in her case, because her father had accepted Romanian citizenship in 1924. Márk’s plan is to establish contact with his American relatives.

Thomas Williams, who repatriated to Hungary in 1989, spoke about his American Hungarian childhood in Washington, D.C., about his mother, who was a refugee from 1956, and his American father. He confessed that despite his mother’s efforts, he didn’t learn Hungarian as a child, though as an adult he caught up and nowadays speaks fluently. He shared stories about his grandfather, who corresponded with famous writer Sándor Márai, was sentenced to death but survived by accident, was later deported to Germany, testified at the Nuremberg Trials, and eventually became a professor at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C.

During the closing roundtable discussion of the event, the participants outlined plans for the next five volumes. Zsuzsa Pócsai has transcribed her grandfather’s diary, which will serve as the basis for the next book. Gábor Gyuricza and Sarolta Kóbori, with the support of the University of São Paulo, will act as editors for a volume titled From the Old Homeland to Brazil. Don Peckham, together with Réka Bakos and Dr. Anna Fenyvesi, will co-author the third volume planned for release in 2026, which will explore the legendary story of students from the Forestry University of Sopron who fled Hungary in 1956. Ibolya Török Sándor is collecting the available family stories of her great-great-grandfather from Homoródalmás (Transylvania, Romania) and the 130 other men living in that area, aged between 17 and 40, who immigrated together with him at the turn of the 1900s. Éva Szabóné Rácz is working on a book planned for 2027 that will document additional family stories of the Dollártanya community.

In her closing remarks, Réka Bakos mentioned that their long-term plans include expanding beyond the U.S., building connections with researchers from various academic fields, and reaching out to younger generations as well.

Related articles: