The following is an adapted version of an article written by Lázár Pap, originally published in Hungarian in Magyar Krónika.

America—the new world, the land of opportunity, the land of the free. In the 19th and 20th centuries, hundreds of thousands of Hungarians left their former lives behind to cross the Atlantic and try their luck Far Far Away, that is, ‘Beyond the Óperencia’, as Hungarian fairy tales go. In its series, Magyar Krónika looks at the meeting points of America and Hungary through the Hungarian diaspora living in the US. In this part, let us continue the story of Hungarian American newspaper owner Joseph Pulitzer, who intervened just in time when the American public and the press were almost on the brink of war.

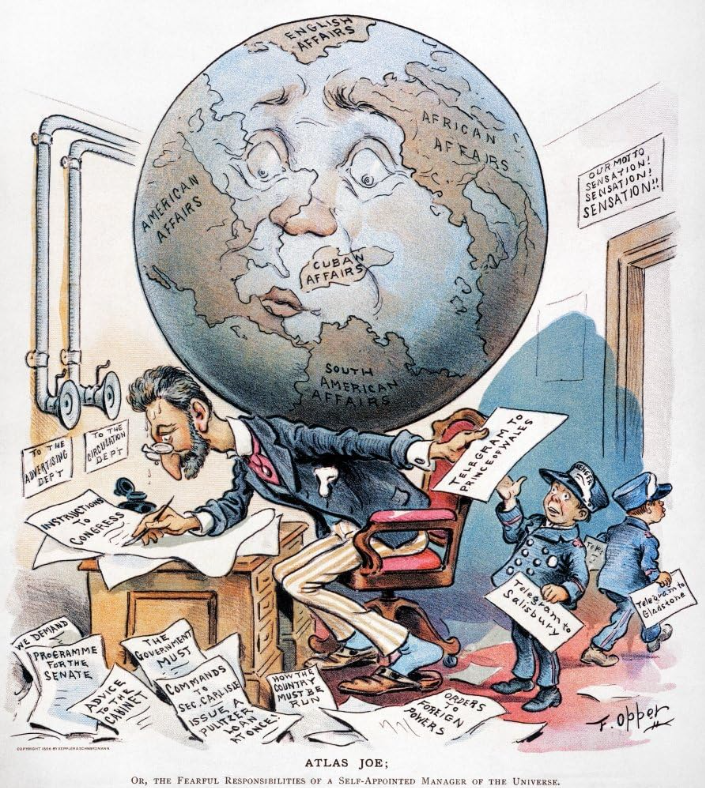

At the end of the 19th century, a border dispute arose between the Republic of Venezuela and British Guiana. The United States sought to act as an arbitrator in the case, but the British refused to yield. The situation continued to escalate, and ‘sabre-rattling’ policies found an ally in the press. Hungarian press magnate Joseph Pulitzer and his newspaper, The World, were at the forefront of efforts to calm the increasingly hysterical mood.

In the second half of the 19th century, the relationship between the Republic of Venezuela and British Guiana, which was in the colonial line, was constantly burdened by border disputes. The conflict escalated when gold was found in the disputed region. In 1887 Venezuela broke off diplomatic relations with Great Britain and, citing the Monroe Doctrine, asked the United States to act as an arbitrator.

‘America belongs to the Americans’—this is how the Monroe Doctrine can be summarized succinctly. Of course, this slogan sounded different in the early 19th century and after the Civil War, when the United States embarked on the path to becoming a great power. American President James Monroe said the following in his message to Congress on 2 December 1823: ‘We owe it, therefore, to candor and to the amicable relations existing between the United States and those powers to declare that we should consider any attempt on their part to extend their system to any portion of this hemisphere as dangerous to our peace and safety. With the existing colonies or dependencies of any European power we have not interfered and shall not interfere…’

‘The United States respected the status quo, meaning they did not interfere in the affairs of the existing colonies’

In essence, the European powers were expected to end colonization, respect the sovereignty of the independent Central and South American countries, and not attempt restoration. In return, the United States respected the status quo, meaning they did not interfere in the affairs of the existing colonies, and they also kept themselves away from European politics. The policy of non-intervention and neutrality—this is how the Monroe Doctrine was described at the time.

In 1895 the American presidency was held by Grover Cleveland, who had been re-elected after a one-term hiatus. As the elections approached, the Democratic politician sought to use the tensions between Venezuela and British Guiana for campaign purposes. He aimed to capitalize on the prevailing anti-British sentiment in the country and the nationalist mood that characterized both Democrats and Republicans. Cleveland readily embraced the cause of the ‘unprotected’ republic against the colonial power, and both the press and public opinion rallied behind him.

The American Foreign Ministry acted radically and provocatively, sending a note to the British government, in which they demanded that an arbitral tribunal settle the border dispute, citing the Monroe Doctrine. They accused the empire of violating the territorial integrity of Venezuela. At first, the British did not even bother to respond to the message, but a few months later, Prime Minister and Secretary of State Lord Salisbury responded. He questioned the international legal significance of the Monroe Doctrine and rejected taking the conflict to arbitration.

However, tensions could no longer be calmed. For instance, New York Police Commissioner Theodore Roosevelt proposed the occupation of Canada should the British refuse to back down.

Cleveland fell into his own trap; the fundamentally anti-imperialist president simply wanted to gain votes with his decisive action, but the people demanded escalation—at least this is what can be concluded from the press reports. After the diplomatic failure, the president, in an effort to save his popularity, fled forward. In his address to Congress, he stated that he would not hesitate to use force to stop the expansion of the British Empire in South America.

‘Cleveland fell into his own trap; the fundamentally anti-imperialist president simply wanted to gain votes with his decisive action’

He came up with a new plan, which called for the establishment of a congressionally approved commission to settle the border dispute. ‘In making these proposals, I am fully aware of the responsibilities and consequences that may follow…’* the president ominously concluded his speech. The public and the press were almost on the brink of war. The president’s message was carried to schools, and Civil War veterans also offered their services.

Meanwhile, both houses of Congress had accepted the proposal and voted $100,000 to establish an ‘independent’ committee of inquiry. Britain was now beginning to grasp the magnitude of the problem. The American press continued to inflame public sentiment. The Sun branded anyone who did not stand by the president a traitor: ‘Not an hour can be lost in preparing to do the duty incumbent upon our country,’ they wrote. The New York Times and The New York Tribune sought to ridicule those advocating a peaceful resolution.

Of course, calmer voices were also present, but they were not the majority. Among the more prestigious newspapers, for example, The New York Herald, Joseph Pulitzer’s The World, and The Evening Post stood against the public mood and advocated for a peaceful settlement. The latter expressed the situation as follows on 18 December 1895: ‘It is sad and shocking that anyone who holds the high office of President of the United States should simply play a political game on the great question of war and peace.’

Pulitzer set himself the goal of ‘cooling down’ the nationalist mood of the country. In his articles, he explained why, in his opinion, the Monroe Doctrine could not be applied to the conflict between Venezuela and British Guiana. He emphasized that intervention was not in the interest of the country, but only of the president. His paper advocated neutrality in a multitude of leading articles and editorials, and tried to control the hysterical public mood, but Pulitzer soon had to realize that rational arguments would not be enough.

He saw the need to appeal to emotions and began writing articles about the importance of Anglo–American relations and the friendship between the two peoples. He announced a peace rally on 20–22 December 1895 and sent hundreds of telegrams to English public figures.

‘A few peaceful, friendly words that will help restrain the noise, calm the passions, make people think soberly, and prevent misfortunes’—this is what he asked them to publish.

‘With his peace campaign, Pulitzer earned the respect of not only the American but also the British public and gained enormous prestige’

The first responses arrived just before Christmas, which Pulitzer published under the title ‘Peace and Goodwill’. Among those who responded were former Prime Minister Gladstone and the heir to the throne, the Prince of Wales, and his son, the Duke of York. Subsequent monarchs (Edward VII and George V) emphasized that they ‘sincerely believe that the present crisis will be settled to the satisfaction of both countries, and that the same close friendship which has existed between them for so many years will follow’. The British Foreign Secretary could not respond in this way to the request, but his secretary assured the American readership of Lord Salisbury’s friendly feelings.

The intended effect was achieved: the public’s warlike mood began to subside, relations between the United States and Great Britain appeared to stabilize, and from then on, diplomacy between the two nations was marked by a pursuit of peace. The border dispute between Venezuela and British Guiana was ultimately resolved through negotiations, and in 1899 the British colony was awarded most of the contested territory.

With his peace campaign, Pulitzer earned the respect of not only the American but also the British public and gained enormous prestige. He preached the importance of negotiated settlement, peace, and the responsibility of the press. This agio, however, was later destroyed during the Spanish–American War.

You can read about Joseph Pulitzer’s further adventures in Part VI.

This article is based on András Csillag’s work titled Joseph Pulitzer and the American Press.

*This and some other quotes in this article were translated by Hungarian Conservative.

Read the previous parts of the series below:

Click here to read the original article.