The following is a translation of an article written by foreign affairs journalist Mátyás Kohán, originally published on Mandiner.hu.

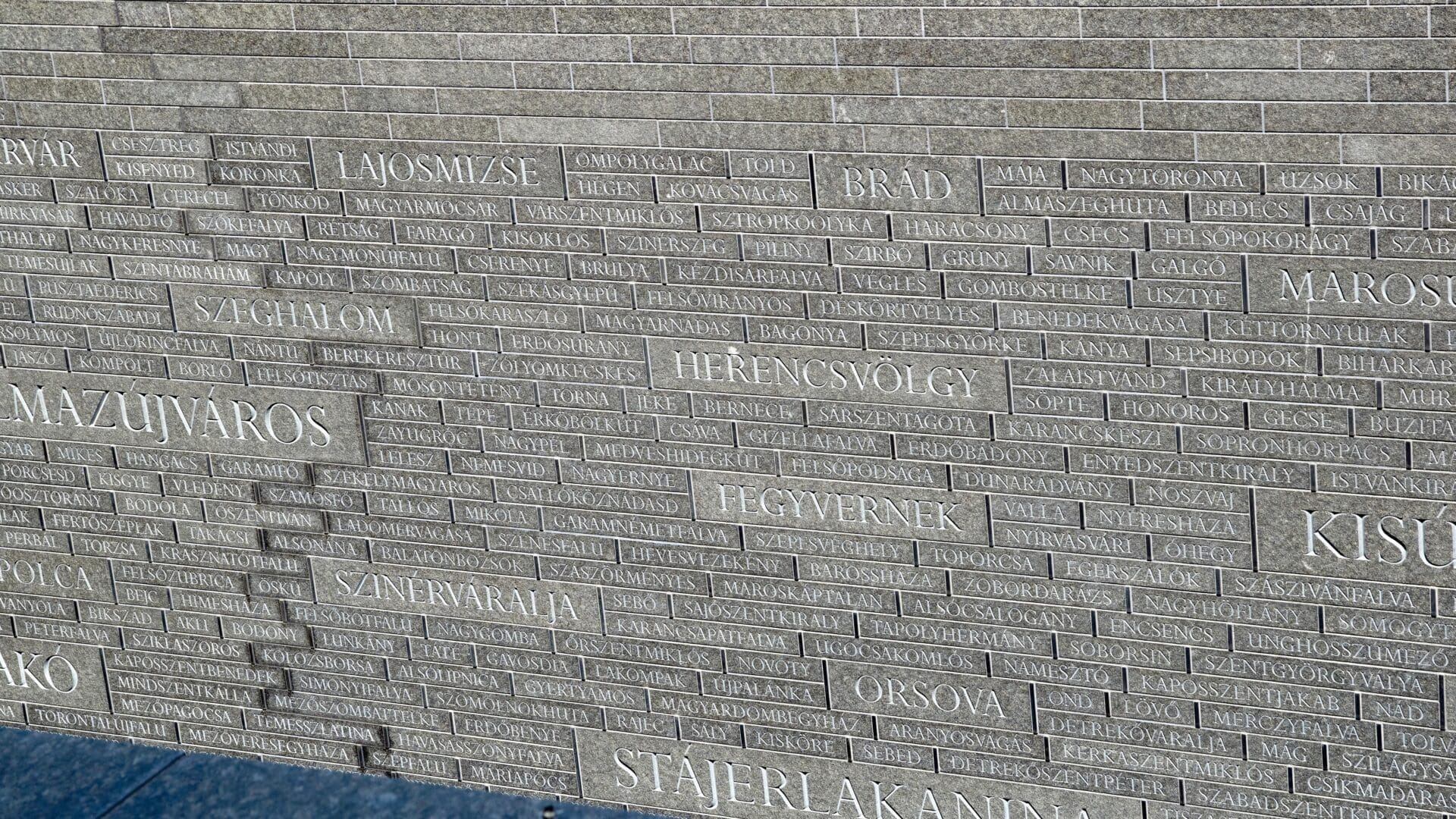

This Sunday, 4 June, we Hungarians celebrate the Day of National Unity, and at the same time, we mourn the Treaty of Trianon. We celebrate and mourn at once, in a way nobody else does—I am not aware of any other nation besides us having such a bittersweet-tasting memorial day.

And we do the right thing when we celebrate and mourn at the same time, because this way, year after year, the whole country is faced with the cold, heavy rigidity of the Hungarian state’s existence. When we moved here to the liveable Carpathian Basin from beyond the Urals—whether from the south or the north, believe it as you like—, we took upon ourselves a whole millennium of isolation. Each of the peoples living around us is more closely related to someone else than to us: they have a common language, a shared consciousness or fate. In addition to the valuable fields of the Kunság and the vines of Tokaj, our postal code also comes with the fact that we do not have, and cannot have, a natural ally. The best examples we can present are the Hungarian–Polish and the Hungarian–Austrian friendships—however, we do not have a relationship similar to that of the Slovaks and the Czechs, the Romanians and the Moldovans, or the Austrians and the Germans.

We were not alone on the side of the Germans in World War I, and perhaps we did not make greater mistakes than anyone else did on that side; in fact, what we did botch, it was together with the Austrians and the Czechs, so to speak. And yet it was us Hungarians that they made an example of. The formula of Hungarian history is harsh and painful because of the loneliness imposed on us by our postal code:

more Hungarian harm comes from a single Hungarian mistake than Austrian or Czech harm from a single Austrian or Czech mistake.

However, this fact should still not lead to an indignant, furious rebellion. All nations got their crosses to bear, and ours is by far not the heaviest—for example, that of the Ukrainians is Russia, that of the Jews is anti-Semitism, that of the Greeks is mathematics, and that of the whole of Africa is colonisation. By contrast, our cross is that we cannot make as many mistakes as any other nation. While other peoples’ mistakes are punished with a slight wave of the hand, ours are with being cut to pieces.

And while our soul secretly longs for revision, believing that, as Hungarian statesman Ferenc Deák, also known as ‘The Wise Man of the Nation’, put it, ‘what force and power take away, time and good luck may bring back’,

it is also worth keeping in mind that as long as we exist, there will always be something to take away from us.

There can always be more ‘Trianons’, smaller or larger ones. For example, a smaller one is withholding the EU Recovery Funds; a medium one is reducing Hungary’s veto rights; and the biggest one imaginable today is called ‘Huxit’. Hungarian foreign policy cannot make mistakes today either, because the formula is cruel: the punishment of the Hungarians always equals the sum of the mistakes of Hungary and the hostility of its external environment. And our country’s external environment does not seem much more Hungarian-friendly today than it was one hundred and three years ago, on 4 June 1920; the improvement in our relations with our neighbours is hardly due to anything other than the fact that they already do have the territories they could claim today. Thus, they have nothing to complain about anymore.

Therefore, in a superhuman and supranational way, Hungarians cannot make as many mistakes as other nations. This is what the Day of National Unity screams into the faces of ten million people every year. Nevertheless, it is important that this day is not only a day of pain and bitterness, on which we remember the good times while contemplating revenge. May this day also be the day when, contrary to the will of so many, we turn to our still-existing and beautiful country, which is prosperous to an extent never seen in history before, and consider, each and every one of us, how we can help it make no more mistakes. Because, as we learn it over and over again on every 4 June, we are less free to do that than anyone else is.

Click here to read the original article.