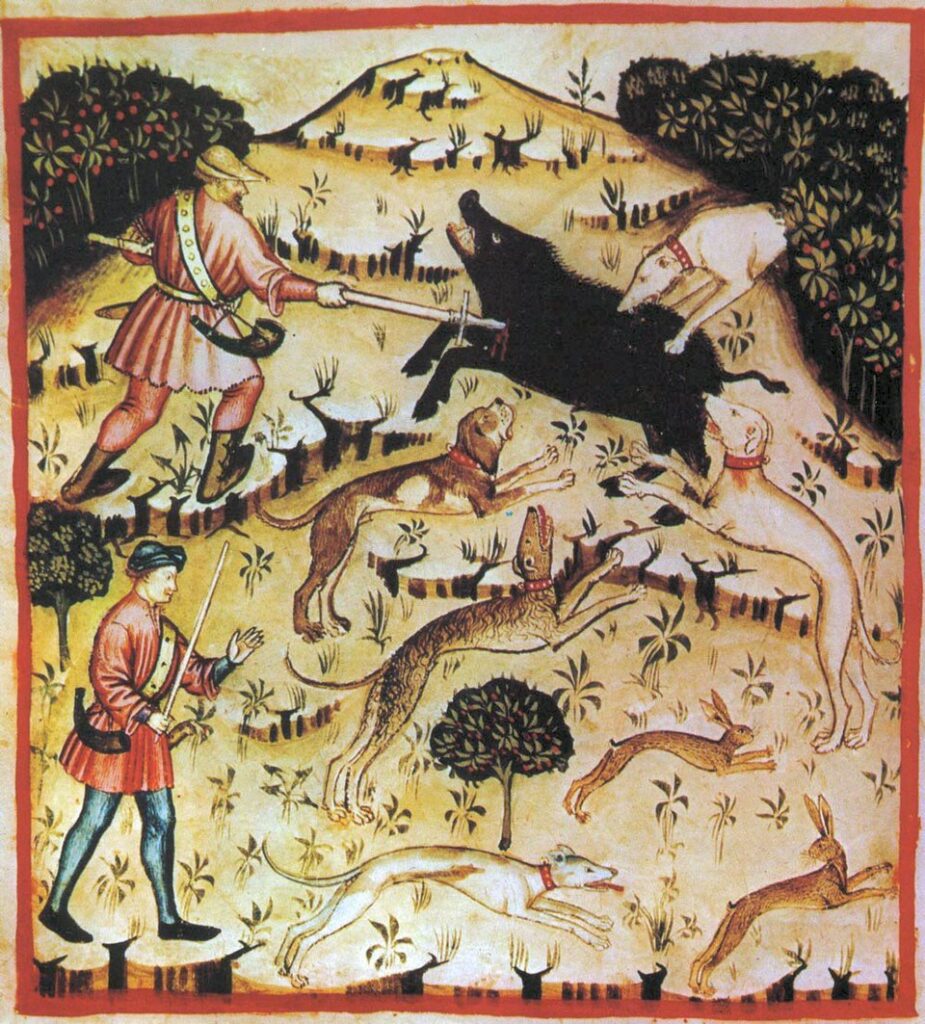

The death of rulers and their burial places were of particular interest to medieval chroniclers. Most rulers died of some unspecified illness, some died from injuries sustained during battles for the throne, and only a few were victims of murder. The deaths of Hungarian Kings Louis II (d. 1526) and Władysław I (d. 1444) in battles against the Turks ensured them eternal glory, with the latter still being referred to by the Poles as ‘of Varna’. Hunting accidents and encounters with wild boars or bears were more common, but except for Prince Saint Emeric (d. 1031), these were rarely fatal, as in the case of King Emeric (r. 1196–1204) and Louis the Great (r. 1342–1382). The participation of rulers in hunting may have been common, but it may indicate something extraordinary when we read in a document of King Andrew II that he marked the tree in Slavonia where he took down a wild boar. Political violence did not become commonplace in Hungary before 1301, apart from the murders of the pro-German Queen Gertrude (1213) and King Ladislaus IV (1290). Nevertheless, regicide was not uncommon in the 11th century. The power struggles of the 11th century often ended tragically for kings cornered by rebels, as was the case with Samuel Aba in 1044 and his rival King Peter Orseolo in 1046.

Strangely enough, King Béla I lost his life in 1063 in an accident, or—as has recently been suggested—as a result of a political conspiracy, before even encountering the German troops attacking him. The latter would not be entirely surprising, given that 15 per cent of European rulers living between 600 and 1800 ended their lives as victims of political murder, and it is well known that ruling was one of the most dangerous occupations in the Middle Ages.[1]

Articles keep popping up on the Internet claiming that King Béla I of Hungary died in Dömös when the throne collapsed on him in the royal palace, writing that ‘the king suffered an accident that is quite rare in world history—he was crushed by his own throne’. Basically, there is no problem with this, as this is still the common belief about the death of King Béla, and it can even be read in textbooks.

‘Ruling was one of the most dangerous occupations in the Middle Ages’

However, if we examine the question more closely, we arrive at a somewhat different conclusion. In a Hungarian chronicle copied in the 1350s but based on 11th-century reports, the so-called Illustrated Chronicle, we can read about the death of King Béla on 11 September 1063: ‘When the most pious King Béla had completed the third year of his reign, he was severely injured on his royal estate at Dömös when his throne collapsed, and thus suffered from an incurable illness.’[2]

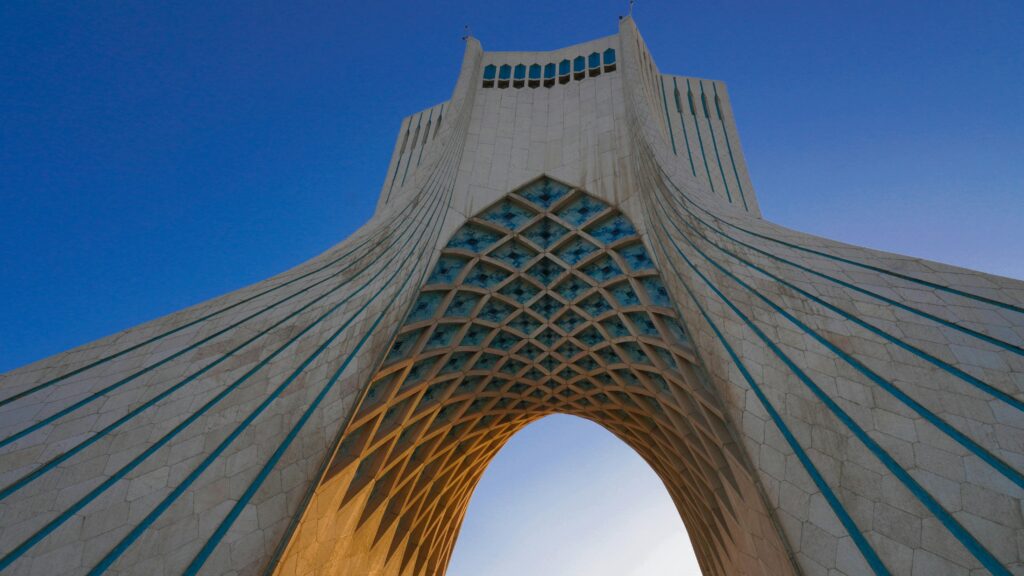

The quote above is the traditional translation, which has always caused problems due to the use of the Latin word ‘solium’ (throne). However, it is difficult to imagine the story, even if we think of a large canopy throne structure like the one shown on the cover of the Illustrated Chronicle.

In fact, according to the chronicle, it was not the throne itself, but rather a wooden structure, the upper level of which may have collapsed. The Latin name for this structure, or more precisely, the upper terrace, was ‘solarium’, a word very similar to the Latin word ‘solium’, meaning throne, which also appears in the Bible. The word ‘solarium’ had several meanings in ancient times. It could refer to a timekeeping device based on the movement of the Sun, the aforementioned upper terrace, or even a building tax. Today, of course, everyone thinks primarily of the device that aids cosmetic tanning, the ‘sunbed’, in which the word sun (sol) can also be found.[3]

In the quoted chronicle passage, the word ‘solarium’ may have been replaced by the almost identical ‘solium’ due to textual corruption. The textual corruption may therefore have been the result of a copyist’s abbreviation, with the syllable ‘lar’ being shortened from the longer word ‘sol(ar)ium’ to the shorter ‘solium’, and now only marked by an abbreviation sign. Later copyists did not recognize the abbreviated syllable, but it is even more likely that they were unfamiliar with the term ‘solarium’ in an architectural context, which was popular only in Western Europe. The later usage of the word also points to the royal court, where it was used to refer to the king’s private quarters on the upper floor.[4]

‘The textual corruption may therefore have been the result of a copyist’s abbreviation’

The solarium was therefore a multi-story building mentioned and described several times in Carolingian manors, and even in the court of Charlemagne himself in Aachen, specifically its upper floor, a covered gallery where the ruler and his closest entourage were seated. In fact, it was this upper level that was called the solarium. It is no coincidence that we find the Latin word ‘sol’, meaning ‘sun’, in its name, as it was indeed closer to the rays coming from the sky. According to another etymology, it may derive from the Latin/French word ‘solus/seul’ meaning ‘to be alone’, or perhaps their meanings became contaminated. We have hardly any archaeological sources on Hungarian examples of this type of building. In Hungarian usage, one of the rare mentions of solarium—perhaps not coincidentally—occurs in connection with the summer residence of the Italian-born Ippolito d’Este, Archbishop of Esztergom, built between 1487 and 1490 in Pusztamarót.[5]

According to archaeologists, early manor houses may have been two-story stone buildings sunk into the ground, with the lower level serving as storage space. The case in Dömös shows that they could also have been made of wood, at least on the upper level. It does not seem unreasonable to assume that the collapsed building contained a gallery, a structure not uncommon in Western Europe, reminiscent of the representative, multi-story royal palace chapels associated with manor houses. The two-story building convincingly radiated royal authority, the image of the ruler looking down on his subjects from above, representing and symbolizing the sacred nature of the royal sphere, close to the heavens. It is reasonable to assume that Dömös also had a building of this type, suitable for more serious, but at least temporary court stays.

Accidents similar to the one in Dömös were also recorded in Carolingian annals. According to the description by the anonymous author of the Fulda Annals, Louis the German, King of the East Franks, set off for the West in June 870: ‘But on the way, he was resting in a certain gallery when the building collapsed, and he fell with it and severely bruised his limbs.’[6] The accident took place at a royal court near present-day Bonn, known in German as Pfalz, but unlike the Hungarian king, Louis the German survived. The same incident was recorded by another contemporary chronicler, Regino, Abbot of Prüm, who is often mentioned in connection with the early history of the Hungarians. Regino’s description is even more vivid: the king went up to the upper floor (solarium) of the manor house with his large entourage. However, the building collapsed due to its old and rotten beams, burying the ruler beneath it. King Louis broke two ribs, and those around him could hear the rattling of the broken ribs for quite some time after the accident.

Accidents involving the collapse of buildings were not unprecedented, and similar cases are reported from later centuries. A miracle attributed to St Dunstan of Canterbury is connected to a similar event that occurred at a church council in 976. The saint and his entourage miraculously survived. The most famous case occurred on 25 July 1184, when, during a German national assembly, the ceiling of the second floor of the provost’s building next to the church in Erfurt collapsed under the weight of those present. Dozens of those who fell to their deaths in the latrine below, but King Henry VI of Germany remained unharmed.

‘Accidents involving the collapse of buildings were not unprecedented’

Sources are silent about the members of the Hungarian royal court, which makes the description from Dömös all the more valuable, as it confirms that the King was accompanied by a large entourage to the royal estates in the royal forests. The most distinguished among them must have crowded around him, unwittingly causing the tragedy. Even serious researchers have suggested that there may have been some kind of conspiracy, an assassination disguised as an accident, which would not have been surprising given the tense political situation at the time. The king had just gone to war against the German King Henry IV, who was attacking the country alongside Solomon (r. 1063–1074), the pretender to the throne. Similarly, a political assassination is suspected in the case of Prince Saint Emeric’s hunting accident as well (1031), which deprived King Stephen I of his only surviving heir.

The most famous and still controversial hunting accident in Hungarian history happened to Miklós Zrínyi in 1664. Zrínyi was the greatest Hungarian politician, poet, and legendary military commander of the 17th century. As the Ban of Croatia, he opposed the Austrian emperor’s policy toward the Ottomans. The accident happened two days before the nobleman, considered by many to be a ‘rebel’, was to leave for Vienna to negotiate the defence of Hungarian territories with the emperor. It is mainly based on the events of 1664 that people believe that the unexpected death of a Hungarian prince or king was the result of an assassination organized by the ‘Germans’.

However, suspicions of assassination in 1664, 1063, and 1031 are completely unfounded. There is no reference to a possible conspiracy in contemporary sources from 1063. Based on all this, it is most likely that King Béla I was fatally wounded by the beams of the royal palace’s unexpectedly collapsing floor, and not by the throne chair set up in the building, or even less so by conspirators.

[1] Manuel Eisner, ‘Killing Kings: Patterns of Regicide in Europe, 600–1800’, The British Journal of Criminology, Vol 51, Issue 3, May 2011, p. 556.

[2] János M Bak and László Veszprémy (eds),Chronicle of the Deeds of the Hungarians from the Fourteenth-century Illuminated Codex, Budapest–New York, CEU Press – OszK, 2018, p. 185.

[3] In English, it lived on in the form of ‘solar’ and ‘solar tower’, referring to the private apartments on the upper floors of manor houses. Besides, the word can be identified in the German name ‘Hohenzollern’, where the German ‘Söller’ (terrace) also derives from the Latin word ‘solarium’.

[4] Mayke de Jong, ‘Charlemagne’s Balcony: The Solarium in Ninth-Century Narratives’, in Jennifer R Davis and Michael McCormick (eds), The Long Morning of Medieval Europe, Burlington, 2008, pp. 277‒289.

[5] István Feld, ‘A nyéki királyi épületek. Késő középkori curia–villa–aula–vadászkastély–nyaraló a budai hegyekben’, in István Feld and Selysette Somorjai (eds), Kastélyok évszázadai, évszázadok kastélyai. Tanulmányok a 80 éves Koppány Tibor tiszteletére, Budapest, 2008, p. 38.

[6] The Annals of Fulda, ed and transl by Timothy Reuter, Manchester, 1992, p. 62.

Related articles: