O Albion, land of common law, of Magna Carta, of habeas corpus, of Catholic Emancipation, of John Stuart Mill. Whose people ate their identity cards after the Second World War. A land of genteel civilian policemen, who once patrolled neighbourhoods unarmed in order to prevent real crime, but who now turn up at pensioners’ houses with tasers to arrest them for thought crime.

To outsiders, Britain seems to have degenerated from a nation of ancient liberties under its crown into a police state, where one is just as likely to be pardoned for savaging a young girl as to be punished for tweeting an inflammatory opinion.

In 2023 over 12,000 members of the public were arrested for posts online. Police have recorded hundreds of thousands of lovely-sounding Non-Crime Hate Incidents—any speech that someone complains about, which will show up on an enhanced record check and can be used as justification by an employer not to offer a job.

Such are the facts Toby Young presented at the MCC (Mathias Corvinus Collegium) in Budapest last week to a mystified audience.

Young, recently elevated to the House of Lords, has transitioned from a provocative columnist who, in 2018, felt the sharp end of archaeological offence digging to arguably the foremost holder of the torch of liberty in the United Kingdom, as founder of the Free Speech Union. His organization provides support to many of the thousands of people accused of speech offences. In some cases, it will fund the whole of their defence.

Since most police forces are working overtime on hate crimes, the union’s membership has grown from 12,00 in June 2024 to 40,000 a few months ago, and is projected to reach 50,000 by the year’s end.

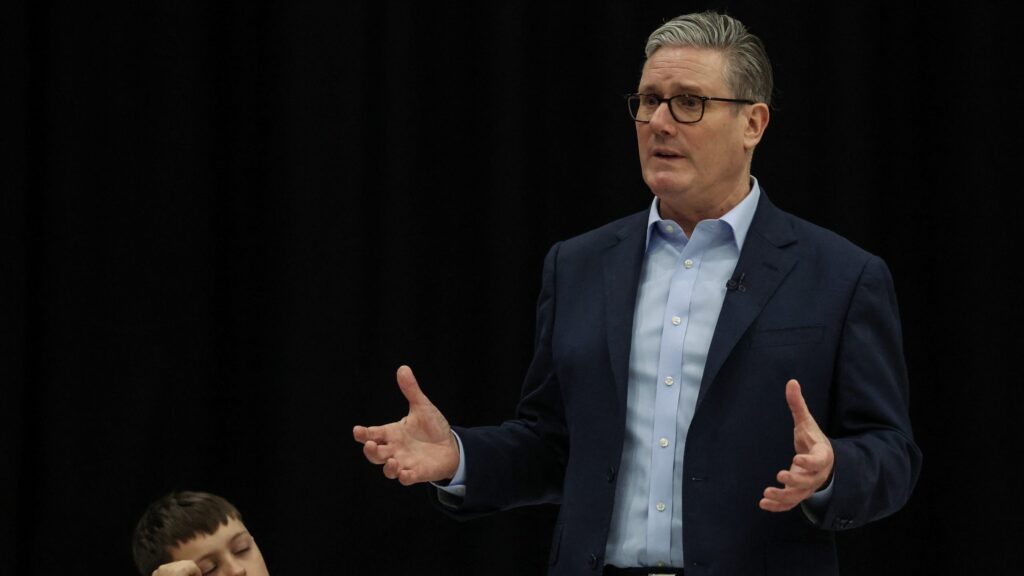

It is a misconception that the present Labour government is directing the activity of the fuzz, and that Britons are living under their yoke. Although the police may feel emboldened to act under Sir Keir Starmer’s administration, as Young explained, there are three laws by which poor souls are being apprehended and prosecuted, all of which have been on the statute book for some time.

For anything said in public, there are general provisions under the Public Order Act 1986, for anything communicated in writing, there is the Malicious Communications Act 1988, whereby one can be found guilty of an offence if it causes ‘distress or anxiety’ to the recipient, or section 127 of the Communications Act 2003, whereby one can found guilty of an offence if the communication is ‘grossly offensive’.

‘For anything said in public, there are general provisions under the Public Order Act 1986, for anything communicated in writing, there is the Malicious Communications Act 1988’

So we still live by the rule of (vague) law. But the fact that only 10 per cent of those arrested in 2023 were convicted of a criminal offence suggests both that the police are being overzealous and that, to some extent, sanity is prevailing amongst magistrates and juries.

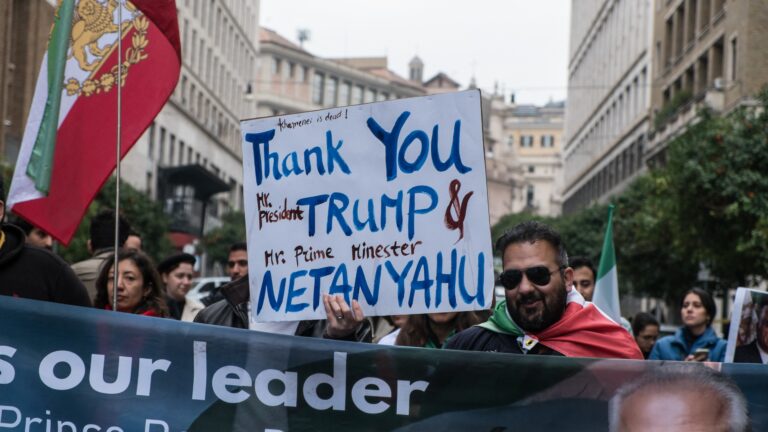

Young’s interlocutor, Boris Kálnoky, reasonably asked why these laws exist in the first place. Young suggested that they stem from the ruling class fearing the volatility of the white working class man and that Britain’s towns and cities are tinderboxes ready to explode. The progressive elite wish to contain community tensions like the pre-crime unit in the film Minority Report; they have shifted from a rose-tinted view of multiculturalism to a fatalistic outlook.

Our current ruling class, he said, are like colonial officers whose job it is to contain the indigenous population of their own country.

While the comparison is ingenious, I think Young forgets twas ever thus. The race relations industry has existed since the 1960s. The British elites have been concerned for decades with the nebulous concept of preserving community cohesion from upon high, particularly since immigration from the Commonwealth began to increase. There were calls for Enoch Powell to be prosecuted after every single speech he made on immigration (not just the famous Rivers of Blood), and some of his most virulent opponents were from within his own party, such as Lord Hailsham.

Much of the fear Young describes also exists in institutional memory as an overreaction to events, in the form of the Scarman (1981) and Macpherson (1999) reports. Indeed, it is little known that the recording of Non-Crime Hate Incidents arose from the latter.

There is also much mythology about the British character. We are not lovers of liberty in any pure sense whatsoever. The Covid pandemic revealed that we are a nation of tutters, conformists, and curtain twitchers, busybodies, jobsworths and pettifoggers: every rule worshipper had entered paradise. They brought down a prime minister who was egregious in the literal meaning. People who love to exercise power will exercise it in whatever form is easiest.

So, as progressive ideology is dominant, then unsurprisingly, the police will take complaints from members of sacred identity groups more seriously than from others.

As Young pointed out, for example, this means the complaints of Jews will not be taken seriously. But Muslims? Their voices will be both heard and acted upon.

The painful truth is that most people only care for free speech in the abstract when it serves their interests. In living memory, Britain had a figure called the Lord Chamberlain who censored theatre performances for moral rectitude. When the state was conservative, the left used to be the greatest advocates for liberalization, until they had marched through the institutions, they wished to entrench their views.

‘This means the complaints of Jews will not be taken seriously. But Muslims? Their voices will be both heard and acted upon’

I do not recall former Guardian columnists like Suzanne Moore and Hadley Freeman, or feminists like Julie Bindel and leftist academics being interested in free speech until they realized it was difficult to criticize the cult of transgenderism. Few men wish others to be free to attack what they consider sacred, yet all men wish to be free to attack what they consider profane.

The minority who desire protections for dissenters, whatever the orthodoxy may be, have two primary recourse to action: purge the institutions of the types of people who want to further specific political agendas, or compel them not to do so by legislation. Young believes that the legality of speech in Britain should be subject to the Brandenburg test (the ruling of the US Supreme Court, which interpreted the First Amendment as permitting all speech unless it is intended to and is likely to cause ‘imminent lawless action’). Although there has never been anything approaching an absolutist tradition of free speech in Britain, his innovation would have obvious merits, not least of which is promoting a society where people of all stripes cease to whine about being offended.

If Young is correct that it will be a political battle even within the Conservative Party to persuade it to adopt this test, perhaps he might have more luck with Reform UK?

Related articles: