If we ask anyone today about Saint Martin of Tours, the answer would be that he was a Frankish saint who, as is well known, was the most important patron saint of the French kings before Saint Denis. His most revered relic is a piece of a cloak cut up for the poor. The modern word ‘chapel’, meaning the place where the relic was kept, also comes from the Latin term ‘cappa’. Clovis I (r. 482–511), king of the Franks, vowed to be baptized at the tomb of St Martin in Tours before the battle against the Goths. Later, the Frankish kings took Martin’s cloak with them as a relic on their campaigns. Martin was already a warrior saint among the Franks, and he presented himself as such in the Kingdom of Hungary.

Of course, it is strange that a warrior saint is one who refused to fight in the Roman army. According to legend, after hearing the Lord’s call, he asked to be dismissed from the army. The emperor, a lover of pagan philosophy, Julian the Apostate (r. 355–360), branded this as cowardice, to which Martin replied: ‘If you disparage my request as cowardice and not faith, then tomorrow I will stand defenceless in front of the battle line, and in the name of Jesus, with the sign of the cross, without shield or helmet, I will penetrate the enemy.’

Nevertheless, countless victories throughout Europe, including Hungary, were attributed to the saint’s heavenly intercession. It is no coincidence that in the most popular medieval hagiographic manual, the Golden Legend (Legenda Aurea), the author explains that Martin got his name from the Roman god of war: the saint bore the name Mars in the sense that he waged war against sins and guilt.

Martin died in 397, and the Martyrology of Saint Jerome sets his feast day on 11 November. He has been celebrated in Rome since the sixth century, and Pope Symmachus (498–514) even dedicated a church to him, founded during the reign of Pope Sylvester I, which was the first church in Rome to bear the name of a non-Roman saint. The church is called San Martino ai Monti in Italian, meaning St Martin in the Mountains, and in the 16th century it became the cardinal titular church of the Hungarian Archbishop of Esztergom, Tamás Bakócz (1500–1521).

‘Countless victories throughout Europe, including Hungary, were attributed to the saint’s heavenly intercession’

Yet, Martin is somewhat Hungarian, too, as he was certainly born in Roman Pannonia, in the western part of present-day Hungary, around 316. His first biography was written by his student, Sulpicius Severus, who noted his birthplace in the very first sentence of the second chapter of the work: ‘Martin, then, was born at Sabaria in Pannonia’. This was adopted by later biographies as well and even became part of the church liturgical reading, and thus the whole thing became known throughout the Christian world. During his campaign against the Avars in 791, Charlemagne, king of the Franks, may have visited the ruins of ancient Sabaria, which were even more impressive than they are today, perhaps because of the veneration of the saint.

Sabaria is well-known for being included on the first medieval world maps, such as the Hereford Map (1300), although only three other cities of medieval Hungary are listed on it. Due to his Pannonian origin, many French medieval sources in the late Middle Ages present him as a Hungarian saint, even of Hungarian royal origin. According to these, Martin’s grandfather was Florus, the king of the Huns, or, in the terminology of the time, of the Hungarians.[1]

Whether this place is the Roman city called Savaria/Sabaria, the present-day city of Szombathely, or the Benedictine Abbey of Pannonhalma, next to which a stream called Sabaria flowed, has been the subject of heated debate since the 19th century. The currently accepted view considers Szombathely to be Martin’s birthplace, where legend has it that the St Martin Church, rebuilt several times, was built on the foundations of Martin’s natal home. The well in front of the church was referred to as St Martin’s Well already in the Middle Ages. At the turn of the 17th and 18th centuries, an educated aristocrat, Palatine of Hungary Count Pál Esterházy, said that ‘our glorious St Martin’ was baptized with the well’s water. Whichever Sabaria it was, all of them belonged to the former province of Pannonia and are located in the territory of present-day Hungary. Although we do not usually mention St Martin among Hungarian saints, we could rightly do so, because he is the patron saint of the Abbey of Pannonhalma, which can be considered the cradle of Hungarian Christianity, and whose charter was issued by the first Hungarian king, Saint Stephen.

The charter issued by King Stephen in 1001/1002 made the figure of Martin part of the myth of the founding of the Hungarian state. According to the charter, Stephen had to fight for the throne with the leader of the Somogy region, Koppány (also called Cupan), and before the victorious battle, dated 997, he sought Martin’s help. The passage reads: ‘I have vowed to St Martin, if by his merits I conquer my internal and external enemies, that what is due from the above county [Somogy] after all its things, possessions, land, vineyards, sowing, tolls, as well as the wine of the guests, which is grown on their estates, shall not belong to the diocesan bishop, but rather I should submit it to the abbot of the same monastery without delay…and when, having made up my mind, I have won the victory, I have endeavoured to put into effect by effective action what I have decided in my mind.’[2]

His legend is worded as follows: ‘And because Pannonia glories in being the birthplace of the blessed prelate Martin, and it was under the protection of his merits that the king faithful to Christ… wrought a victory over the enemy.’

Later, during a pagan attack, Stephen named Martin as his protector and leader again. He said the following: ‘Depart, depart, for my Emperor granted me a defender and a leader, namely, Martin, who will not endure that the pastures of the just be ravished by your fangs!’[3]

‘St Martin remained closely associated with the Hungarian royal dynasty throughout the Middle Ages, and his feast day was made mandatory by the 1093 synod’

The question may arise as to whether Martin could have been remembered in the Carpathian Basin in the 11th century. We certainly cannot assume continuity between the 4th and 11th centuries, even though there were scattered Christian populations in the southwestern parts of the Carpathian Basin who lived through the Hungarian conquest.[4] Martin was an imported saint, and his veneration and biography, written by Sulpicius Severus, may have been brought to the West by Western missionary monks. This is all the more likely given that, until the establishment of the Archdiocese of Esztergom, the Hungarian territories belonged to the Archdiocese of Mainz, whose patron saint was Martin. Further evidence of early veneration is that after Martin, from 391 onwards, the feast day of Brice, the fourth bishop of Tours and Martin’s holy deacon, was celebrated in Hungary on 13 November. It is no coincidence that, according to the earliest surviving Hungarian book list, written around 1093, the library of the Benedictine Abbey of Pannonhalma had 80 volumes, including the work of Sulpicius Severus. St Martin remained closely associated with the Hungarian royal dynasty throughout the Middle Ages, and his feast day was made mandatory by the 1093 synod. In medieval Hungary, there were hundreds of churches dedicated to St Martin, bishop and confessor, and in the 13th century, the royal chapel in the Buda royal castle was also dedicated to him.

After the Árpáds, Martin played an important role in consolidating the power of the Anjou Dynasty as well. The Árpád Dynasty died out in 1301, and several people claimed the throne. The popes supported the Prince of Naples, Charles Robert, who later became King of Hungary (r. 1308–1342), and to this end, they sent Cardinal Gentilis de Montefiore to the country as legate in 1307. It is an interesting coincidence that Gentilis’ titular church was the same as that of the later Hungarian Tamás Bakócz, St Martin in the Mountains in Rome. For Charles Robert, gaining the throne was the result of a long struggle; he was crowned three times before the Holy Crown was finally placed on his head. After the legate who had greatly assisted the Anjou family in ascending the throne left Hungary in 1311, he commissioned Simone Martini, the star of Sienese painting, to paint a chapel dedicated to St Martin in the lower church of the Franciscan basilica in Assisi for 600 Gold forints. In addition to the legend of St Martin, Simone Martini also painted a picture of St Elizabeth of Hungary in Assisi. He then painted the Hungarian holy kings on the altar of St Elizabeth in the basilica. The coronation of King Charles Robert was captured around 1317 in a fresco in the provost of Szepeshely (now Spišské Podhradie, Slovakia). On the north wall, Mary, patron saint of Hungary, crowns the Anjou king, while on the south side, there is the figure of St Martin on horseback, who was also the patron saint of the church. It is no coincidence that Simone Martini was thought to be the creator of the fresco, but unfortunately, this assumption is unfounded.

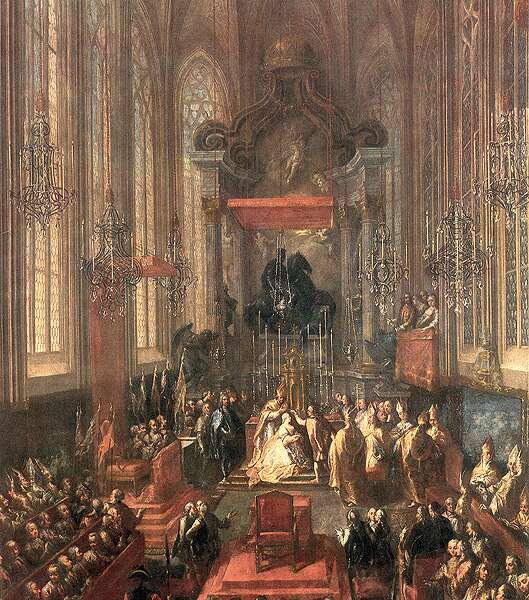

Churches dedicated to St Martin played an important role in the coronation ceremonies of Hungarian kings, too. From the Provost Church of Our Lady in Székesfehérvár, the newly crowned king went to St Martin’s Church, from whose tower he signalled with sword strokes in the four directions that he would defend his country from enemies attacking from any direction. The Ottoman conquest reached Székesfehérvár in 1543, and after the capture of Buda, Hungarian kings were crowned in the new capital of Pozsony (now Bratislava, Slovakia). Between 1563 and 1830, 19 royal coronations took place in St Martin’s Cathedral in Pozsony. The 150 kg, 1.5 m tall, gilded royal crown, which is a 19th-century replacement for the original 1765 tower decoration, can still be seen from afar on the tower of the cathedral. In the 18th century, the Gothic altar in the Pozsony church was replaced by a Baroque altar, on which the equestrian statue of St Martin by Georg Raphael Donner was placed in 1736. Martin, dressed in a Hungarian hussar uniform, is cutting his cloak in half, giving one half to a poor beggar.

‘St Martin’s Day, 11 November, has been an important closing day of the economic year since the Middle Ages’

St Martin’s Day, 11 November, has been an important closing day of the economic year since the Middle Ages. Around this day, animals were brought into the barn for the winter, and shepherds settled their accounts for the year. From the Middle Ages, a rare folk custom, still popular today, was associated with the holiday: the consumption of goose dishes. According to an old saying, people ate goose and drank new wine on the feast day of the holy bishop, which was the last notable day of the year, the last holiday before the 40-day fasting period before Christmas. The custom was traditionally explained by a scene from the saint’s legend: Martin humbly hid in the goose pen so that he would not be elected bishop, but the geese betrayed him with their cries.

In Hungary, Martin’s memory is preserved not only by goose dishes but also by the Benedictine Abbey of Pannonhalma, which is still active and thriving today. The significance of Pannonhalma was succinctly summed up by President Tamás Sulyok on the occasion of the 800th anniversary of the reconstruction of the medieval abbey in November 2023: Pannonhalma, dedicated to St Martin, known in medieval times as the monastery of St Martin’s Hill, ‘was born together with the Hungarian state, its history written alongside that of the nation, while St Martin’s Hill became one of the most important symbols of Hungarian Christianity’.

[1] Levente Seláf, ‘Saint Martin of Tours, the Honorary Hungarian’, Hungarian Historical Review, Vol. 6, No. 3, 2016, pp. 487–508.

[2] László Veszprémy, ‘Religious Rites of War in Medieval Hungary. A Reconnaissance’, in Radosław Kotecki, Jacek Maciejewski, and Gregory Leighton (eds), Religious Rites of War beyond the Medieval West, Vol. 2, Central and Eastern Europe, Leiden, Boston, 2023, p. 170.

[3] ‘Lives and Deeds of Saint Stephen’, transl Cristian Gaşpar, in Gábor Klaniczay, Ildikó Csepregi, and Bence Péterfi (eds), The Sanctity of the Leaders. Holy Kings, Princes, Bishops and Abbots from Central Europe (11th to 13th Centuries), Budapest, New York, 2023, pp. 57, 95.

[4] Endre Tóth, Imre Takács, and Tivadar Vida (eds), Saint Martin and Pannonia: Christianity on the Frontiers of the Roman World: Exhibition Catalogue, Pannonhalma, 2016.

Related articles: