There are probably as many nations that pride themselves in an ancient Roman legacy as there are countries in Europe now. A Roman aquila (eagle) and its derivatives alone have been featured on the coats of arms of countries ranging from Germany, Albania, Serbia, Russia, and the United States to Romania (a country the very name of which is a reminder of the long-gone Empire and speaks a language descending from Latin).

Historically, a multitude of states have referred to themselves as the ‘new Rome’ in an attempt to establish themselves as rightful successors to the ancient, glorious Empire. To a degree, these self-proclaimed titles do match reality—Roman law, Roman philosophy, and the Latin language constitute a very concrete legacy, not to mention the physical heritage, the art and culture of the Roman times that have shaped not just the West, but the entire human civilization. Therefore it is no surprise that many nations emphasize their real or perceived continuity with Rome.

As Hungary has always been devoid of imperial ambitions, it has never asserted itself as an empire descended directly from Rome. In fact, Hungarian national consciousness rather

favours the Hunnic Myth, which traces back the genesis of the Hungarian nation to the Huns and their leader, Attila the Hun,

who were the enemies of both the Eastern and the Western Roman Empires, and significantly contributed to their ultimate demise. Moreover, there is a region in Hungary with a distinct cultural identity known as the Jászság, whose local ethnic identity connected the Jász people to the Sarmatians, the Iranian-speaking nomads who also raided the Roman Empire.

However, as subdued as it may appear at first, the link between Hungary and Ancient Rome is stronger than one might imagine. The Roman Empire has etched an indelible mark on the Hungarian cultural landscape.

First and foremost, Hungary does derive its legitimacy from Rome. Even though it is not always emphasized, the symbolism of the Holy Crown of Hungary features both Roman and Greek—i.e., Byzantian, which in European culture was perceived to be Roman, too—saints and encryptions. The Crown itself consists of two parts, the Corona Graeca (‘Greek crown’) that serves as the base, and Corona Latina (‘Latin crown’) that is represented by four gold strips welded to the top and surmounted by a cross. What the symbolism means is that the legitimacy of the Hungarian Crown, and via it, the Hungarian Kingdom itself, is derived both from Rome and Byzantium.

Furthermore, the esteemed status of the Latin language led Hungary to adopt it as the official language once the country was established, and it remained the language of administration, liturgy and ceremonies until 1844. This, in fact,

makes Hungary one of the last European countries that abandones Latin as the state language.

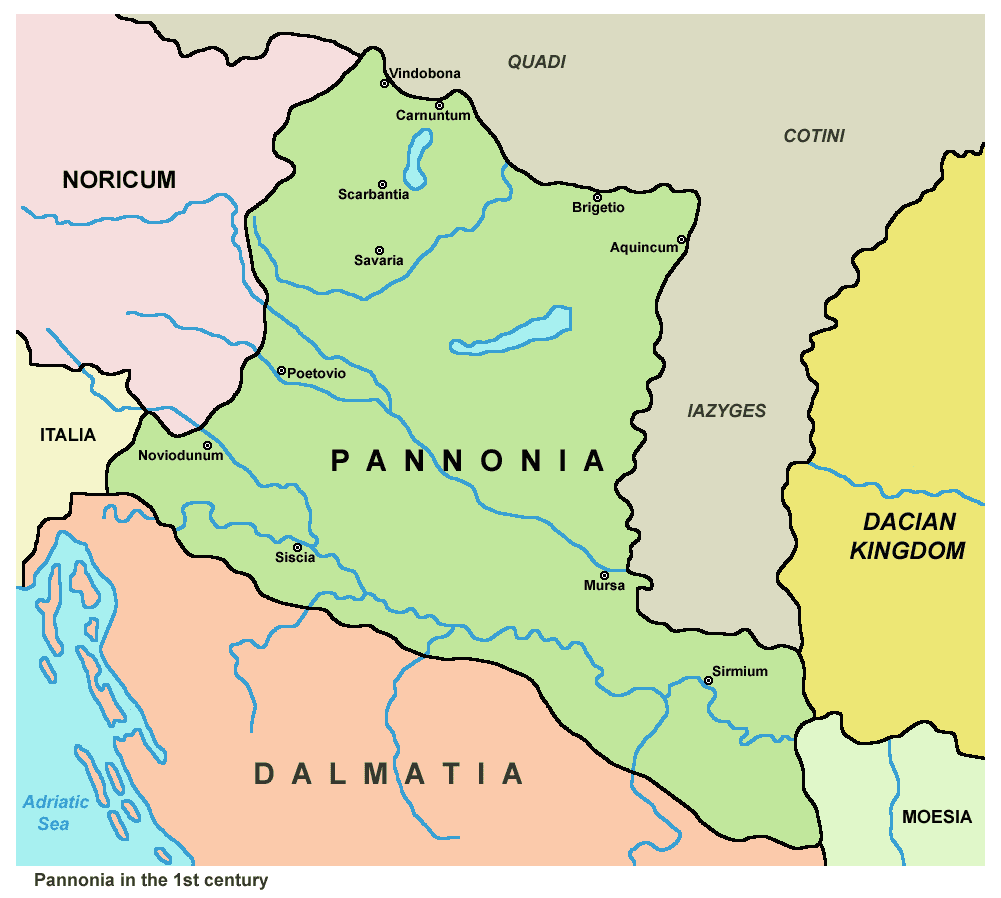

But there are very concrete reminders of the Roman heritage of Hungary as well: the Western parts of Hungary used constitute the Roman province of Pannonia, a land that served as a buffer zone, a bulwark protecting the Empire from the perils posed by the steppe peoples, especially after the Romans retreated from Dacia. Thus, the region was heavily fortified. Many Hungarian cities were founded as Roman forts and towns, among them are Sopron (Scarbantia), Szombathely (Savaria), Visegrád (Pone Navata), and, most famously, Budapest itself, within which the ruins of Aquincum are located.

As far as built Roman heritage in Hungary is concerned, it is most probably Aquincum that first comes to mind. The settlement was erected on the site of a Celtic town called Ak-ink, which roughly translates as ‘Abundant water’, referring to the thermal springs situated in the vicinity of Aquincum. After its establishment in the mid-first century by Emperor Vespasian, Aquincum quickly became a point of attraction for many inhabitants of the Roman Empire, as the lands surrounding the city offered lucrative agricultural opportunities.

In its heyday, the town boasted as many as 40,000 residents.

Since the settlement was a focal point in the systems of fortifications called ‘Limes Sarmatiae’, (The Limes of The Sarmatians, also known as Ördög árok or Csörsz árka in Hungarian),which served as a defence against barbaric invasions, a huge Roman military garrison was stationed here. Aquincum even had a palace built for Emperor Hadrian. The city grew to such importance with time that in 106, Emperor Trajan made Aquincum the capital of the entire province. In addition,

Aquincum was one of the sites where Emperor Marcus Aurelius worked on his famous Meditations.

Symbolically, more than a thousand years later, the new inhabitants of the region, the Magyars, also started to rule the Pannonian Basin from that same place. Today, the remnants of this glorious past can be discovered in the Aquincum Museum.

Outside of the Transdanubia region, the only contemporary city that is located on the site of an ancient Roman fort, is probably only Szeged. Recent research suggests that Szeged was erected on the ruins of the old Roman fort of Partiscum, although, unfortunately, practically no architectural evidence has been preserved.

But the Romans did make it to other parts of the Great Pannonian Plain as well, erecting their system of defences, the aforementioned Limes Sarmatiae. The remnants of this once massive line of defence are today, at best, low stone walls, still visible in some parts of Hungary, including both banks of the Danube River.

In addition, there are numerous other captivating sites showcasing Roman architecture in Hungary—and not only ruins turned to rubble. Some of the Hungarian efforts to preserve the Roman legacy include a full reconstruction of the Iseum Temple in Savaria, now Szombathely, considered to be the oldest Hungarian city. The temple, dedicated to the Egyptian goddess Isis, whose cult spread to many parts of the Roman Empire, was fully rebuilt. Today is the third largest standing temple in the world dedicated to Isis.

For every Roman Empire enthusiast Sopron is an essential destination to be included in their travel list. The city, formerly known as Scarbantia, was located on the ancient ‘Amber Road’ trade route, which connected northern Europe with the Mediterranean. The walls of this strategically important Roman fortress stand to this day.

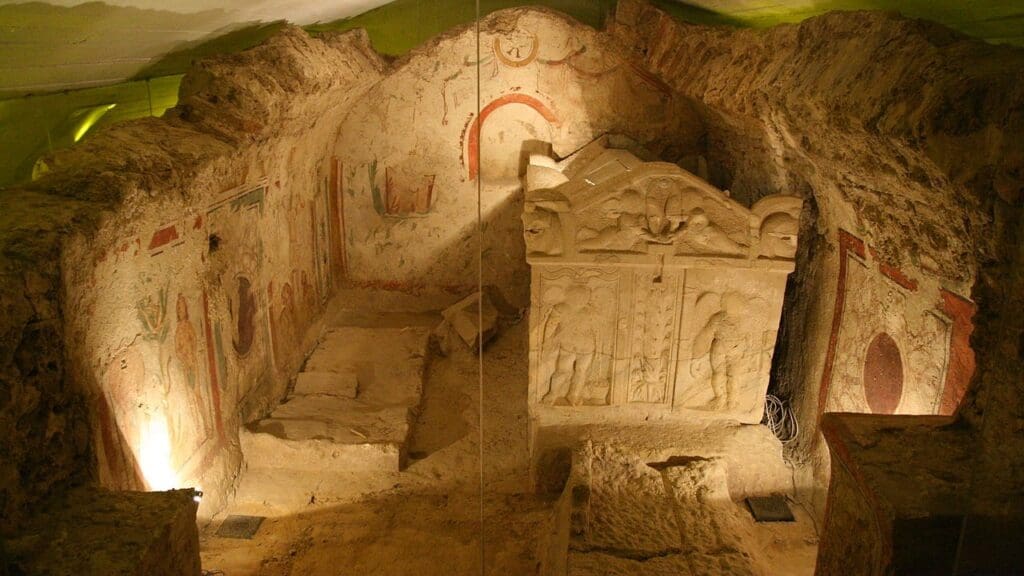

Upon travelling to Pécs, it is definitely worth visiting an old Christian burial site from the 4th century. The old cemetery of Pécs, which back in the day bore the name Sopianae, contains an underground mausoleum decorated with murals depicting Christian themes, indicating early Christian presence in Hungary. This burial chamber is famous for the fact that it is the only UNESCO heritage site from Hungary that won this title in the category of culture–historical architecture.

The list is by no means exhaustive, as there are numerous other noteworthy Roman landmarks in the country, all worth exploring, including but not limited to the Ruin Garden of Savaria, the military camps of Gorsium and Brigetio, the Villa Romana Baláca, and a multitude of others. The rich Roman cultural substratum present in Hungary underscores how remarkable the Hungarian land is, and how epic the tale of its past is. This outstandingly rich legacy has been partially shaped by the Roman Empire, and Hungary's undeniable connection to it is among the things that firmly establish Hungary as a rightful and an inalienable member of Western Civilization.