We have recently delved into the captivating background of the Kunság, a region known for its natural beauties and historical significance as an autonomous region for the Kuns or Cumans, a Turkic-speaking people. The Cumans were first invited to Hungary as they were fleeing from the Mongolian invasion, which pushed them out of the Eurasian steppe in the first half of the 13th century. While the relationship between the Hungarians and Cumans was characterised by ups and downs over the centuries due to the two nations’ divergent lifestyles, cultures, and loyalties, over the course of centuries the Cumans were gradually assimilated into the Hungarian identity.

Kunság is not unique, however, in the sense that it was established for accommodating non-Hungarian arrivals. In their desperate flee from the steppe, the Cuman groups were followed by the Jász (Jazones in Latin), a tribe of people of a completely different origin. Although the Jász shared the nomadic lifestyle of the Cumans, they had a different linguistic, historical, ethnic and cultural background. As our previous article was dedicated to the Cumans, this article explores the rich history of the Jász people. Although modern-day descendants of the Jász are practically indistinguishable from other Hungarians, the Jász have preserved their special sub-identity and are still proud of their unique heritage. The territory that they have been inhabiting for some eight hundred years is known as Jászság even today.

On the map of contemporary Hungary, Jászság does not exist by itself as an administrative region, but is incorporated into Jász–Nagykun–Szolnok County. The strong association between the Jász people and various locations within the historical territory is evident, as reflected by the names of many places, such as Jászberény, the seat of Jászság. In fact, only two of the 18 settlements of Jászság do not have the word ‘Jász’ in their names.

Unlike the Turkic Cumans they initially arrived in Hungary with, the Jász are believed to be descendants of the Alans,

who, in turn, are related to the Sarmatians. The Sarmatians were Iranian-speaking nomadic groups from Antiquity known for their raids of the late Roman Empire. Presumably felt threatened by the Mongolian expansion into the steppe, certain Alanic tribes embarked on a journey westward alongside the Cumans. Eventually, both groups found refuge in Hungary after being granted admission by King Béla IV. Those Alanic groups who did not flee and remained in the Northern Caucasus are now known as the modern Ossetians. Ossetians live in Russia and Georgia and can trace their lineage back to the Alans who did not join the fleeing tribes.

Despite being initially welcome, the coexistence the Jász and the Hungarian natives was not unproblematic in the beginning, even though Béla IV granted the guest tribes special privileges. The king needed both the Cumans and the Jász badly in order to have a greater chance at fending off the Mongol attack. Despite an apparent shared interest in defending themselves from a common enemy, the linguistic, religious and ethnic divide between the Hungarians and the Jász proved to be significant. The complaint of peasants and landowners about the nomadic groups roaming over their fields and crops, was worsened by the rumour that the Jász were spying for the Mongols. Tensions significantly escalated after some Hungarian noblemen murdered Khan Köten (Kötöny in Hungarian), the leader of the Cumans. The nomads fled the country, pillaging and looting in retaliation.

However, after the end of the Mongol invasion, many Jász returned to Hungary, filling up the ranks of the Hungarian military. It happened approximately at this time that Jászság appeared on the map of Hungary as a distinct autonomous unit within the Kingdom. The need for a Jász region was due to the conditions put forward by Béla that required the Jász to settle down permanently. The Jász contribution to the Hungarian military was significant even a century later. The 1323 charter of Hungarian King Charles Robert or Charles I, who ruled between 1308-1342,

granted the Jász autonomy and various privileges in exchange for military service.

Despite experiencing repeated losses of their privileges, the Jász were resilient through history and succeeded in gaining new privileges from time to time. Following their linguistic and national assimilation in the 16–17th centuries, it was their pursuit of regional autonomy that united the residents of Jászság, and which instilled a sense of ethnic consciousness that made the Jász feel distinct from other Hungarians.

One of the most significant loss of rights occurred following the Rákóczi war of independence, after which the Jász had their privileges revoked at the Szatmár Peace Conference as a form of punishment for their collaboration with the rebels. Despite the curbing of their rights and their assimilation, the ancient autonomy of the Jászság survived until 1876, when it was finally merged into the new county system that was established as part of the modernisation of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Jászság has a number of attractions that are worth listing. One important site to visit is, of course, the town of Jászberény, which is home to a prominent Franciscan monastery.

While historic sources are quite limited on the religious beliefs of the Jász, most probably during their migration to Hungary, they followed a peculiar blend of Eastern Orthodoxy and pagan beliefs, possibly including Tengriism, shamanism, and remnants of ancient Indo-European beliefs. After many unsuccessful attempts by the Hungarian rulers and priests to convert them, the Jász still held on to their old beliefs. Nevertheless, the determined efforts of the Franciscans ultimately succeeded in bringing the Jász people into the fold of Western Christianity. As a reward for their success in converting the once pagan tribes, the Pope decided to gift the monastic order with the monastery in Jászberény, which is Franciscan even today. The Jász are still predominantly Roman Catholic by faith.

A significant tourist attraction of the county is the annually held Csángó festival.

The event has been organised regularly since the fall of communism, when, on the one hand, borders became more permeable, and on the other hand, Hungarian scholars and enthusiasts could contact the far-away Csángó population much more often than before. The Csángó are a Hungarian ethnic group who have lived isolated from their motherland for centuries, and have heroically preserved their Hungarian identity and Catholic faith despite enormous assimilation pressure from the Romanian-speaking majority. The Csángó live mostly in Romanian Moldova, the seat of which is Iași, or Jászvásár in Hungarian. As the name of the settlement bears witness, the town was founded by the Jász in the Middle Ages.

In the Jász Múzeum in Jászberény, aside other archaeological, historical and ethnographic exhibitions, the legendary Lehel’s horn is also exhibited. According to the legend, Lehel was one of Grand Prince Árpád’s relatives who participated in the Hungarian conquest of the Carpathian Basin, and the subsequent raids against European kingdoms. According to the ancient legend, Lehel was captured on the battlefield by the army of a German Emperor. When Lehel was brought to him, the emperor ordered him: ‘Choose the manner of your death!’. Lehel, with unwavering confidence, responded, ‘Fetch my horn, and I shall sound it first before providing my answer.’ Once he was provided with the requested horn, he forcefully hit the unsuspecting monarch on the head. The blow allegedly killed the ruler instantly, with Lehel proclaiming: ‘You shall precede me and serve me in the next realm.’ Lehel’s action can be conceptualised as the Scythians’ (ancient Indo-Iranian tribe related to the Jász) belief that those they killed in their earthly life become their personal servants in the afterlife. After his heroic deed, however, Lehel soon had to face his destiny and was hanged in Regensburg.

The horn has been in the possession of the town of Jászberény at least since 1642.

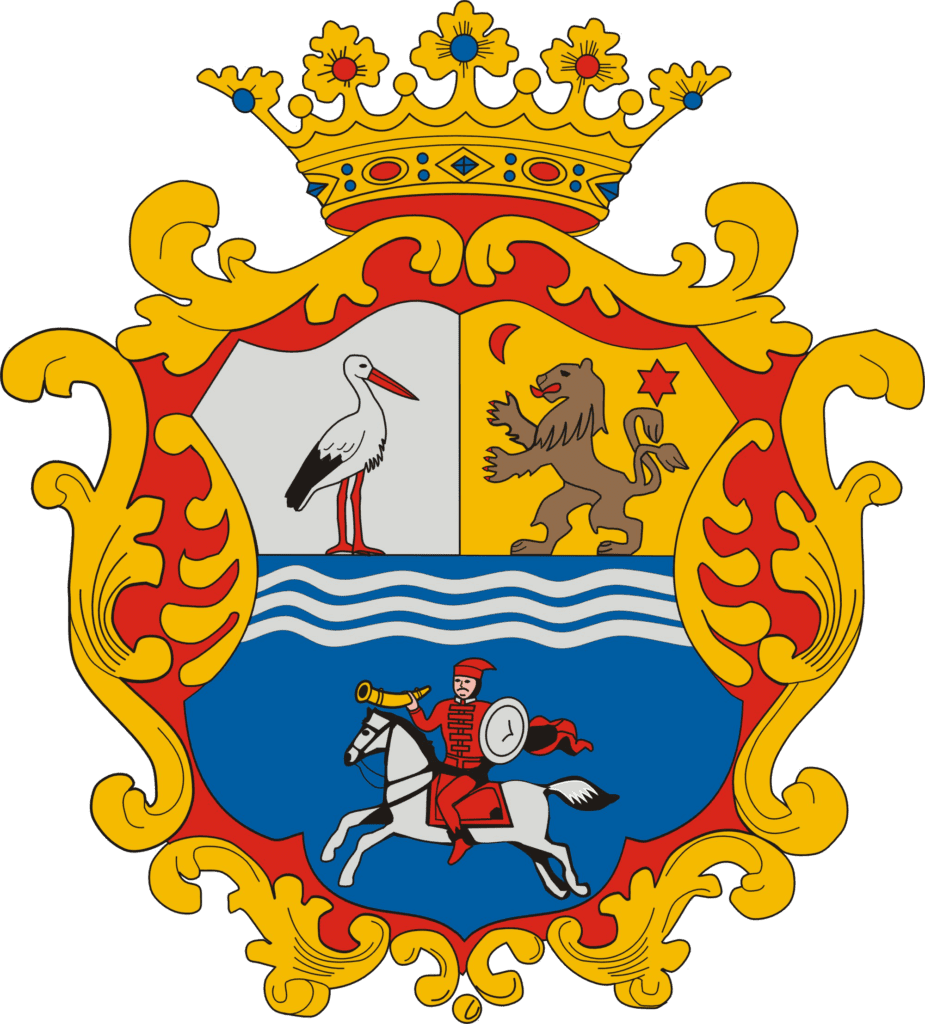

It was used for centuries as a symbol of the power of the Jász chief captains, and was known as the jászkürt (Jász horn) until the end of the 18th century. The importance of the half-mythical horn that in fact dates back to the 12th century is so great for the region’s historical identity that the horn is featured on the coat of arms of Jászberény, as well as on that of Jász-Nagykun-Szolnok County, too.

The history of Kunság and Jászság reveal a lesser known face of Hungary—that of a melting pot. Situated on the westernmost edge of the Eurasian steppe, it experienced the arrival of dozens, if not hundreds of different peoples during the course of its history. Although there were clashes and conflicts initially between the native Hungarians and the new settlers, and also between the various newcomer groups, fundamentally, a peaceful integration and coexistence has been the norm in the country. Condemning Hungary as a racist, xenophobic or culturally intolerant reveals complete ignorance of the country’s historical reality. Of course, our country is not faultless and there are indeed dark and shameful chapters in its history in terms of the treatment of its minorities, but the historical truth is far more nuanced and complex than the simplistic, black-and-white portrayals of today’s Hungary. As opposed to the simplistic xenophobia narrative, Hungary is a multi-faceted country with diverse regions and identities, each of which contribute with their uniqueness to the country’s rich cultural landscape. One of the regions that is a living proof of that is Jászság.