After reading my diaspora books, Dr. Gyula Nádas III reached out to say he felt they could go deeper into the challenges of preserving Hungarian identity in America. Since I had interviewed members of the extended Nádas family before, as well as his wife, Timea Nádas’ half-brother, Gábor Mózsi, I knew both families’ stories were unusual even within the diaspora. We agreed to a joint interview at this year’s ITT-OTT Conference of the Hungarian Communion of Friends (MBK). While we planned to talk about identity and language, a love story of a ‘lost boy’ and a ‘fatherless girl’ also unfolded.

***

‘My wife saved my Hungarian identity,’ you said. Please explain.

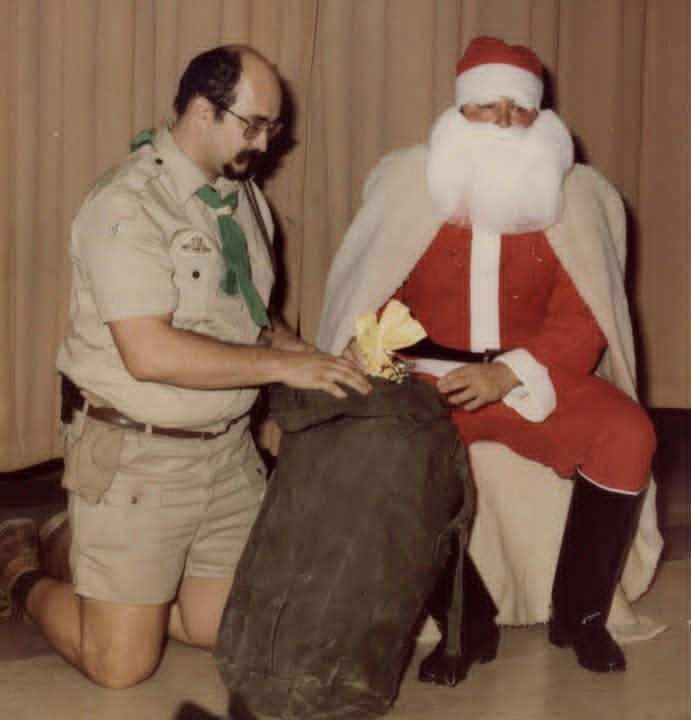

Gyula: We need to go back in time a bit. I’ll try and keep it short: my parents were born in a refugee camp in Austria and came to the U.S. as very young children. They, along with their parents, wanted to preserve Hungarian identity, so we went to weekend Hungarian school and scouting. We are four siblings: Krisztina, me, Zsolt, and Tas. We didn’t attend MBK’s ITT-OTT Conferences because my father was the scoutmaster of the Chicago Hungarian troop, and the summer scout camps usually overlapped. I sometimes wish I had the chance to go; my life may have turned out differently. Hungarian scouting was the Hungarian organization our family supported most, almost as if scouting was more important than being Hungarian.

But Hungarian scouting is Hungarian too; it’s one of the most important diaspora organizations!

Gyula: It’s hugely important, but it can be hard to stay connected once life takes you elsewhere. I have friends who were also raised to think scouting was being Hungarian, and when it stopped, it was easy to lose that identity. The rules said we had to speak Hungarian, but our vocabulary wasn’t strong. We went to summer language camps, where our skills and Hungarian identity improved, but the main goal was still to become a patrol leader. Many drop out around age 14–16; first because of school sports or activities, then college. When scouting is the primary connection, leaving it means drifting from the local Hungarian community. I became an assistant troop leader at 18, then college and career intervened. I never returned for troop-leader training and essentially became the ‘lost Nádas boy’, while my three siblings completed it and stayed strong members of the Hungarian community.

Did you speak Hungarian at home?

Gyula: Yes. Until I was five, it was my primary language, but when my sister started school, we started including more English. With my parents, we always spoke Hungarian, with the vocabulary my grandparents had when they left in ‘45. We didn’t visit Hungary regularly. I went twice in 30 years: once as a toddler, then at 12 for a three-week camp in Fonyód with my sister. Half the participants spoke only Hungarian and half only English; just four of us spoke both, which didn’t necessarily strengthen my Hungarian.

Timea (Timi): What he missed wasn’t only language but living culture. He didn’t receive in the Hungarian weekend school or scouting what would connect his identity to present-day Hungary. When we later worked with 14-year-olds at the Hungarian school, they often thought identity meant folk songs and the Botond–Emőke story for scouting. Today, we travel to Hungary, attend the ITT-OTT Conferences, use contemporary language, and meet contemporary artists, opportunities Gyula didn’t have or didn’t know to take advantage of. We’re not saying school or scouting isn’t good; we’re saying maintaining Hungarian identity can’t depend on it alone, because a teenager may not feel it’s ‘cool’ enough to continue.

Gyula: Moreover, in many cases, children feel pushed, which can make it harder to develop genuine interest and doesn’t make the language attractive. It doesn’t necessarily spark Hungarian-ness or a longing for the mother country.

How did your siblings experience all this?

Gyula: It seemed like Krisztina basically ‘jumped into’ being Hungarian as she set herself an expectation to master language and culture. Her husband served in the U.S. Navy, so they moved often, but she always sought out Hungarian scouts wherever they lived. I think for her it meant identity and community. She always attended summer leadership training in Fillmore, NY, and there was a time when she drove hours just to take her five children to Hungarian school.

Zsolt also scouted a lot. He fell in love with a visiting Hungarian scholarship recipient and followed her to Hungary, where they now live with three children. He often says he lives at a crossroads: considered American in Hungary and Hungarian in America, so a difficult identity.

‘We’re not saying school or scouting isn’t good; we’re saying maintaining Hungarian identity can’t depend on it alone’

Tas is different again. Perhaps he took scouting most seriously, wanting to follow the older siblings. It wasn’t only a circle of friends; he could be with cousins close in age. He finished high school at 16, moved to Cleveland for college, and stayed, where he now started a family. He doesn’t feel ‘homesick’ for the mother country. For him, Hungarian identity lies in Cleveland with scouting and the Regős folk-dance group.

So, for you, being Hungarian means something more, and you feel longing for Hungary. What happened after leaving scouting and the local community?

Gyula: I finished my doctorate, became a pharmacist, and started a family in the suburbs of Chicago. I had no time for anything else. I married an American woman, who had a three-year-old daughter from a previous relationship, and together we had three sons: Xander Gyula, Maddox János, and Draven László. The boys spoke a little Hungarian because I spoke it with them. But Hungarian wasn’t central in my life then, so it wasn’t central in theirs. When it turned out that one of my sons had a speech disorder, the speech therapist recommended speaking only one language with him; his mother latched onto that, and I didn’t resist. Ironically, he now speaks the best Hungarian vocabulary and accent, and also knows Spanish and sign language. He’s also visited Hungary several times, even without us. The boys started Hungarian school only after my 2014 divorce; by then, they were seven, nine, and 11. They were too old to start scouting; that piece was missing.

Timi: My husband is the third Gyula Nádas. Xander, as the oldest, felt this name had, in a sense, been taken from him, so he began changing the order of his given names, so Gyula comes first. Despite obstacles, the seeds of identity are there…

Gyula: After the divorce, I didn’t know what to do with my life. I felt a deep lack of Hungarian identity, even though I could barely speak since I hadn’t spoken Hungarian regularly for 13 years. I wanted to rebuild my relationship with the Hungarian community. Timi says that when she was younger, I was known as the ‘lost Nádas’. If I hadn’t divorced, I might have remained lost. I see it in others’ lives: if there is a gap of ten years or more of participation, it’s hard to reverse course. At the Gala Balls, Gulyás Festivals, or the annual Hungarian Club picnics, many people tell me they once spoke Hungarian, but then moved away or had an American spouse, stopped speaking, and gradually forgot. Now, only flavors and snippets of folk songs remain. That’s what I feared all my life…

…and that’s what Timi saved you from. How did you meet?

Gyula: Timi is the sister of my childhood friend and scoutmate, Peter Zalai. After my divorce, I visited Peti’s house for a barbecue, bringing my boys and hoping to reconnect with Hungarians I hadn’t seen in a decade. Timi was there.

Timi: Gyula introduced himself and said he hadn’t known I existed. I replied that I knew who he was and that he didn’t know me. It flustered him right away…

Tell us also who you are!

Timi: We often say we don’t have a family tree but a bush. I was born in Chicago as the second daughter of Ági and Feri Mózsi, younger sister to Anikó. From a previous marriage, my mother had a son, Peter. My father had a son in Hungary, Gábor. After 23 years, my parents divorced; my father remarried and later had a daughter, Panni. I’ve traveled to Hungary almost every year, mostly with my grandmother and mother, who ran the Sebők travel agency for 23 years. Since infancy, I’ve spent summers in Csobánka near Szentendre, at a small house on top of the Pilis hills. At 15, I’d decided to move to Hungary, not only because of those summers but because my father had moved back for cancer treatment. I planned to move after finishing high school, but he died in 2007 before I could. My plan remained, and I moved when I turned 18.

At your father’s funeral, you were 16 and met your 13-year-old half-brother, Gábor, for the first time. How did you process that?

Timi: With difficulty. Even a divorce is hard for a teenager to process, let alone such a complex situation. It turned out later that my dad had several romantic relationships. We first heard about Gábor maybe just a few weeks before the funeral. I still find it hard to forgive my father for denying my half-brother’s existence, even when I asked him about it directly. Gábor and I met for the first time at his funeral. I think both of us are still trying to process all of this…

Sometimes I am angry with Dad, sometimes deeply ashamed of what he did, especially toward his children. At the same time, I love and respect all that he did for the Hungarian American community. He connected Chicago and Budapest, American life and Hungarian identity, the local and Hungarian organizations and artists. He accomplished something wonderful that, for example, Gyula felt was missing. But while doing all this, unfortunately, my father failed to see that he wasn’t paying enough attention to his family.

Researchers say that in many cases, when a person experiences trauma, developmentally, they remain, in some sense, at the age when it happened. Since I experienced my father’s death as a trauma during adolescence, the returning anger sometimes feels like that of a teenager. Yet rationally, I know, especially as a 34-year-old parent of five and as a psychotherapist, that in most cases every parent gives what they are capable of in their child’s upbringing. Perhaps my father, too, lived his life that way: giving what he could—the fact that that was lacking may have been hindered by his own upbringing or traumas.

Did you resent your father more then, or now?

Timi: My anger is focused more on the situation itself and on how much pain and suffering arose from it. While I greatly value my father’s work, the Hungarian community, and art, it’s thought-provoking that what he had too little attention left for was his family. It must also be said that the zeitgeist, or the spirit of the age, and the broader culture play a role here. I’m not talking about ethnic culture now, but rather about the fact that in earlier times, it was perhaps less expected that fathers should actively raise their children. Moreover, it was often somehow ‘accepted’ that an artistic soul could live a bohemian life, having multiple romantic relationships and several children.

As for us, when one of Gyula’s main goals became ‘maintaining the Chicago Hungarian community’, I was happy for him, but I also felt that finding a balance between family and Hungarian identity is important. I think this is something Gyula works hard to achieve, which is crucial, especially being involved in so many communities. Yet I see that his hierarchy of values is clear: family and health come first (including family’s health), and everything else, including his work for Hungarians, comes right after that.

Gyula: From all this, Timi taught me: when you say yes to something, you don’t realize how many things you’re saying no to. When I threw myself into community life and said yes to volunteering, she warned me to think carefully about my yeses because with each yes, I might be saying no to family.

While she helped you reconnect with your roots, you helped her make peace with losses; you also gave back to her what life had taken from her…

Gyula: Yes, I think we are each other’s saviors.

Timi, let’s go back in time: you went to Hungary at 18. How was it?

Timi: I moved to Hungary because I was searching for my roots and because being in the Chicago Hungarian environment seemed unbearable at the time. At first, I went to the Balassi Institute on a scholarship and tried to write my thesis about my father, but I fell into such a deep depression that I couldn’t even write about him. On the other hand, I had become even more attached to Hungary. I loved being home. I grew up with the feeling that that’s where home is: we always spoke of Hungary as home. You can feel your roots there. When I worked near St. Stephen’s Basilica, it was pure joy to take the 4 or 6 tram across Margaret Bridge, see the Parliament, and walk to work. It touched spiritual strings in me like the Pilis hills in Csobánka. In that environment, I experienced happy moments, unlike the U.S., which I had fled and where, upon returning, I felt unbearable homesickness. But I met this amazing man there…

How did meeting Gyula become love and marriage?

Timi: After five years in Hungary, I returned to Chicago for an extended visit because my grandfather, Béla Szilágyi (my mother’s adoptive father), became ill. My half-brother, Peter’s baby, was born then, another reason to stay. When we met at that barbecue, I wasn’t sure whether Gyula was interested romantically or only as a friend. When I asked him, he answered: ‘I don’t know. I find you interesting, but I have children, and they are my top priority.’ I replied to him: ‘If you had answered anything else, I wouldn’t be as interested.’ In the end, instead of Hungary, I chose Gyula. From a healthy-environment perspective, my home was Hungary; in reality, I found my true home beside him.

What did your mother say about Gyula, who was divorced, had three boys, was 15 years older than you, and hardly spoke any Hungarian?…

Timi: First off, it helped that our families knew each other.

Gyula: One of my best childhood memories is that we’d go to the library with my mom, then walk to Timi’s grandmother’s pastry shop, where Klára gave me a habcsók, my favorite. Also, her mother ran a family daycare that my brother Zsolt and Anikó attended.

Timi: In the beginning, my mom worried about what I’d do with three boys. But she came to know him and later said: ‘Perhaps I never really loved men at all, but I love Gyula.’

What about Gyula’s three boys? How did they react to Timi?

Timi: We saw each other often at Hungarian school and events. The children knew who I was, but not as their father’s new partner.

Gyula: That lasted until one day, one of the boys asked me: ‘Apuka, wouldn’t you like to date someone?’. I asked if they knew someone who could be a good partner. They mentioned someone I couldn’t imagine, so I asked again. This time they asked me: ‘What about Timi?’. How could I say no?…

Timi: We married in 2018 in Balatonföldvár, Hungary. When I took Gyula to Balaton, he fell in love with it too. Pretty much everyone we’ve taken, now including our twin five-year-old daughters, Léna and Lilla, loves Balaton and can’t wait to go back.

What was your first ITT-OTT Conference together like?

Gyula: I didn’t know what to expect; it felt like a big family circle. The Hungarian language was hard, but there were other young people in a similar situation who struggled like I did. I liked the music; I remember Ádám Török on the shepherd’s pipe with another gentleman on the citera.

Timi: For me, 2015 was anything but easy. It was my first ITT-OTT after my dad’s death. Before, every Hungarian event, especially this one, meant a shared program with my father. When I returned, love and joy connected to identity, my father, and ITT-OTT got tangled up with trauma and pain. It was hard, but beautiful and important, also cathartic, with more pain than joy at first, which slowly changed. I had wonderful memories here: childhood friends, splashing in Lake Hope with Csilla Megyeri, etc. I wanted the joyful part to blossom, not the pain. At first, emotions overwhelmed me; Gyula supported me through it. Aunt Panni (Nádas) Ludányi also helped us feel at home. It was wonderful to see how much Gyula enjoyed being here and how it rekindled his Hungarian spirit.

So, it wasn’t even a question you would return?

Timi: For me, no. When I asked Gyula if he wanted to come again, he said: ‘We’ll see what the future brings.’ By 2017, we brought the three boys. Krisztina’s son, Józsi, also came that year and now comes every year, at least for a day. He says the place is beautiful and the program is more relaxed than scouting, with time to rest and socialize. There are morning lectures and evening performances; afternoons and late evenings allow friendships to form freely; no coincidence, our name is Hungarian Communion of Friends.

Gyula: There are friendships in scouting, too, but different. Usually, your patrol is your core circle, and you don’t have much time to get to know others; here, you can connect more deeply. We organized the children’s program in 2017. Mostly including outdoor activities, since more than half the group didn’t speak Hungarian, joined the music programs, but couldn’t take part in most lectures.

It’s usually easy to find community tasks, but what about the language?

Gyula: My vocabulary at first was terribly poor. But we spoke a lot in Hungarian, I read a lot, we watched Hungarian films, and traveled to Hungary.

Timi: Gyula doesn’t switch back to English just because it would be easier. Even now, we’re speaking Hungarian.

Gyula: It makes me sad to see how many people don’t speak Hungarian and therefore can’t participate fully in community life. Most stories end like this: ‘I started learning, then stopped, and all that’s left is lángos, palacsinta, and “Az a szép…”.’ The Balassi Program, Rákóczi Camp, etc., help a lot, but even so, we lose countless 15–20-year-olds in Chicago, and only a few come back.

Timi: Alongside language gaps, it seems that traumas often hold people from coming back. When someone comes back after a longer time, they’re often asked: ‘Where have you been, and why don’t your children or your American spouse speak Hungarian?’, instead of saying: ‘It’s so good you’re here!’. Such comments can unintentionally discourage those who want to reconnect.

What can you do?

Timi: We’re trying. The Borozda folk-dance group has been active for years; we asked for a teenage group for those who don’t speak well. Now the KCSP dancers (the Kőrösi Csoma Sándor scholars from Hungary) have launched one, and we helped recruit. Anyone who wants to live their identity is welcome, regardless of language level.

Gyula: We’re taking this approach with other organizations as well. In the past, spending time together could ‘win people over’, but today they’re not necessarily drawn by that alone. People can help in ways that don’t require language skills. Some have asked why we need scholarships to encourage volunteering. Many young adults haven’t discovered why this identity matters to them yet. If we want to reach, involve, and keep them, and drip-feed some ‘Hungarian-ness’, incentives can help keep them in the community until they figure that out themselves. Reading your books, it struck me how hard it is to be Hungarian in America. Moreover, language isn’t something you learn once; you must develop and use it constantly. Our three boys don’t really speak Hungarian anymore. So, we tried something different with the twins, who now hardly speak English; now we’re a very mixed mosaic family.

What is your goal regarding your children’s identity and language?

Gyula: The boys are 18, 20, and 22; it’s their decision. We gave them the tools. I keep doing what I can to keep them in the community, but for them, Hungarian identity may not be as important.

Timi: Maybe we could have pushed harder, but Gyula’s divorce was difficult. As a stepmother, could I have said: ‘No more English at home’? I couldn’t; our relationship mattered more. According to my values, family and relationships were more important than enforcing language, so we didn’t force it. Besides taking them to Hungarian school, we involved them in volunteer work at Gala Balls, Gulyas Festivals, picnics, and more. Through these, they built connections with other Hungarian kids and with their identity. Coincidentally, last night they hosted a party and invited Hungarians as well as American friends. This shows that through volunteering, they can maintain connections even without strong language. They relate to it differently; for them, it takes more effort. That’s why tools to draw them in and keep them in the community are important.

Gyula: The girls are five, about to become Hungarian scouts, and very excited. They love Hungary and adore ITT-OTT. They are currently homeschooled. So, for now, their Hungarian identity is dominating over their American identity.

And what is your personal goal in this regard?

Timi: When my mother passed away two years ago, I nearly gave up. I felt we wouldn’t be able to carry this on. It became so hard, emotionally and logistically, taking the little ones everywhere. Luckily, I realized that even if we cannot do everything perfectly, we can still do many things well. Back then, it simply seemed too much. I think it still is, but now we are better at saying no, individually and together. It’s easier now that the girls aren’t so small. We keep talking about what comes at the expense of the family, especially when our daughters ask: ‘Why do we always have to help?’. While we’re still everywhere, we’re working so we don’t have to be everywhere; we try to involve others, widen the community in a way that language isn’t a barrier.

Gyula: For me, it’s simple: family and health come first, Hungarian identity and community come after that, and they are stronger because of that order.

Related articles: