A poll conducted this summer by INSCOP Research in Romania revealed that 66.2 per cent of Romanians considered Nicolae Ceaușescu to have been a good leader, despite the repressive nature of his regime. Only 24.1 per cent of respondents expressed a negative opinion. Even communism itself was viewed relatively favourably: 55.8 per cent of those surveyed judged it to have been ‘a good thing for Romania’, compared with 34.5 per cent who disagreed.

This paradox becomes even more striking when placed in historical context. Romania was the only country in the region that resisted any form of liberalization during the 1970s and 1980s, while it clung rigidly to a Stalinist vision of society and economy until 1989, leading to famine and severe deprivation. The social catastrophe was largely the work of Ceaușescu and his inner circle, who were determined to pursue Stalinist policies at any cost. Yet, as the survey demonstrates, for many Romanians today the so-called ‘Golden Age’ of Ceaușescu continues to evoke memories of stability, welfare provision, and a sense of national unity.

Some analysts have argued that public attitudes toward communism can be explained by the regime’s ability to provide basic necessities such as housing, medical care and education to almost every social stratum—something the neoliberal state after 1994–1995 failed to achieve. This interpretation, however, is misleading. By the mid-1980s, the Romanian state had become almost completely dysfunctional—its only effective branches being the secret police and the propaganda apparatus, while the latter succeeded in constructing a cult of personality around Ceaușescu reminiscent of North Korea or the Soviet Union of the 1930s and 1940s. The Romanian dictator was systematically portrayed as a global statesman whose wisdom supposedly transcended national borders. This relentless personalization of power hollowed out the country’s institutions, turning both the Party and the state apparatus into little more than instruments for glorifying the leader.

‘For many Romanians today the so-called “Golden Age” of Ceaușescu continues to evoke memories of stability, welfare provision, and a sense of national unity’

The propaganda apparatus was refashioned whenever the dictator decreed, an effortless task in a country where, since 1949, no free press had existed and the Department of Propaganda and Agitation had ceaselessly broadcast Party orthodoxy. Meanwhile, the Committee for Press and Printing (Direcția Generală a Presei și Tipăriturilor) stood guard as the central censorship authority, charged with ensuring that no newspaper, radio programme, film, or stage production strayed from Party directives or let slip what counted as state secrets.

Within this institutional structure, state ownership of the press was absolute. For example, the most important newspaper Scînteia (The Spark), the Communist Party Central Committee’s official daily, had been founded back in the 1930s as a party organ; while România Liberă (Free Romania)—another widely distributed daily newspaper—despite its title, was equally under party control. The state’s dual role as both proprietor and ideological overseer left no space for independent editorial policy and as a consequence Romanian journalism functioned solely as a transmission belt for the Party line.

The Mirage of Liberalization

Ceaușescu assumed power in 1965, following the death of Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej from lung cancer, and, in the spirit of de-Stalinization, he set out to fashion an image distinct from that of his predecessor. In the meantime, as relations with Moscow soured, the new leader sought to compensate by cultivating ties with the West, where gestures of openness were rewarded with attention and aid, while artistic and cultural exchanges became the showcase of the normalization of relations. Almost immediately after taking charge of the party, Ceaușescu summoned intellectuals and artists, assuring them that the spirit of de-Stalinization would continue under his rule. He extolled stylistic diversity in art, the use of ‘multilateral forms of expression’, the ‘valorization of the national cultural heritage’, the ‘removal of rigidity and exclusivism’, and the benefits of international cultural contacts.

This new atmosphere of relative liberalization soon made itself felt. Romanians experienced freedoms previously unthinkable: travel abroad became possible—though still barred to those with problematic political pasts—foreign newspapers and books were published, and the circulation of people and ideas widened. The Press and Printing Directorate remained in place, but it no longer wielded the same heavy hand as in earlier years, creating limited room for experimentation, cultural exchange and freedom of expression.

By the early 1970s, this short but fertile contact between Romanian artists and the cultural milieu of Western Europe was already bearing fruit. Works of international caliber appeared, validated both by exhibitions abroad and by prizes won in Paris, Edinburgh, and Berlin. Nicolae Breban, a Romanian novelist, offered a telling example of the atmosphere: in an interview for the French magazine La Quinzaine littéraire, he explained his recent Party membership. ‘I had joined the Communist Party only in the autumn of 1967, and I chose this path because of the growing democratization of social life, and especially of cultural life, that the Party had promoted and encouraged since 1964.’

After consolidating power, Ceaușescu’s first major foreign policy move came in August 1968, when he openly condemned the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia and refused to dispatch Romanian troops to suppress the Prague Spring. This dramatic stance was reinforced by a coordinated propaganda campaign and the first major reorganization of the institutions responsible for ideological control and propaganda. Scînteia ran a series of articles presenting Romania’s position as a moral defence of the idea that every socialist country had the sovereign right to settle its own internal affairs. The paper did not endorse the Prague reformers directly but instead stressed non-interference and socialist unity. On 21 August 1968, Ceaușescu delivered his famous ‘balcony speech’ in Bucharest, broadcast live on state television and splashed across the press, a fiery denunciation of the invasion. The media portrayal was unmistakable: Ceaușescu cast as the fearless leader who stood up for liberty and for his nation, a moment of rare popular acclaim.

In the same time the Department of Propaganda and Agitation was renamed the Department of Propaganda and several new sectors were established within it: Propaganda and Social Sciences, Foreign Propaganda, Mass Political Work, Lectures, and Documentation. The role of agitator was abolished—dismissed by Ceaușescu and the Party as retrograde—on the assumption that the population was now ‘mature’ enough to absorb Marxist-Leninist ideology without mediation. On the other hand, by placing the social sciences under the Department’s authority, the Party ensured that fields such as sociology, philosophy, and history became instruments of ideology. This arrangement also allowed the regime to keep a close eye on intellectuals, even as they gained greater opportunities to travel, study, and conduct research in the West.

These reforms, coupled with Romania’s new foreign policy stance, proved highly effective. Western powers now saw Romania as a socialist state willing to defy Soviet domination, while at home the stance generated mass mobilization and shored up public trust in the regime. Emboldened by this momentum, Ceaușescu became convinced that media and propaganda had to stand at the very centre of political activity, and that mass communication must exploit the newest technologies if it was to maintain its effectiveness.

The July Theses and the Great Retreat

Another major institutional reorganization followed a key foreign policy event in 1971, when Ceaușescu travelled to North Korea and Maoist China. There, he not only found new partners within the socialist bloc who were intent on asserting independence from the USSR, but also encountered a revitalized version of the Leninist strategy of total national transformation. Upon returning home, he delivered a speech before the Executive Committee of the Romanian Communist Party—his ‘Exposition regarding the PCR program for improving ideological activity, raising the general level of knowledge, and the socialist education of the masses, in order to arrange relations in our society on the basis of the principles of socialist and communist ethics and equity’—a marathon text that soon became known as the July Theses, deliberately echoing Lenin’s April Theses from 1921.

In this speech, Ceaușescu denounced ‘bourgeois ideology and retrograde mentalities, alien to the principles of communist ethics and the Party spirit.’ He castigated the ‘comfortable petty-bourgeois complacency’ of intellectuals and their ‘anarchic liberalist’ tendencies, accusing them of surrendering to everything foreign, especially to influences coming from the West. At the same time, he proclaimed ‘the right of the working class to intervene not only in literature but also in the visual arts and music,’ and its right ‘to accept only what corresponds to socialism and to the interests of our socialist homeland.’ In practice, of course, the ‘working class’ meant the Party’s activist apparatus, now endowed with a mandate to police culture once again.

‘The result was predictable: cultural life once again fell under the full weight of Party domination…and was driven into isolation’

Romanian intellectuals were thus instructed to seek inspiration solely in domestic sources—above all, the ‘realities of communist Romania.’ The result was predictable: cultural life once again fell under the full weight of Party domination, as it had during the forced Russification of the Stalin years, and was driven into isolation. In September of that same year, the regime established the Council of Socialist Culture and Education to tighten ideological control across schools, universities, and cultural institutions. This was more than censorship. The Council actively shaped content, dictating curricula, supervising book publishing, theatre repertoires, cinema, and even museums—ensuring that every domain spoke with the single voice of the Party’s new ideological line.

In February 1972, at a meeting with propaganda chiefs, Ceaușescu declared that television must not compete with propaganda but be absorbed fully into its machinery. He feared that unchecked broadcasting—rapidly becoming the population’s favoured form of entertainment—might dilute ideological messaging or distract viewers with non-political fare. Television, like the press before it, was thus placed under strict Party guidance, with news and cultural programming tailored to glorify the leader and conform to the new ideological line.

Ayear later came institutional consolidation: the creation of the Department of Propaganda and Press, comprising divisions for Propaganda, Political and Educational Work, Cadres and Educational Work in Schools and Faculties, and Press, Radio, and Television. This reform further centralized Party control, allowing Ceaușescu to dictate the direction of Romania’s cultural life more directly. By bringing the press, radio, and television under a single institutional umbrella, the regime eliminated any possibility of divergence between media outlets and official messaging.

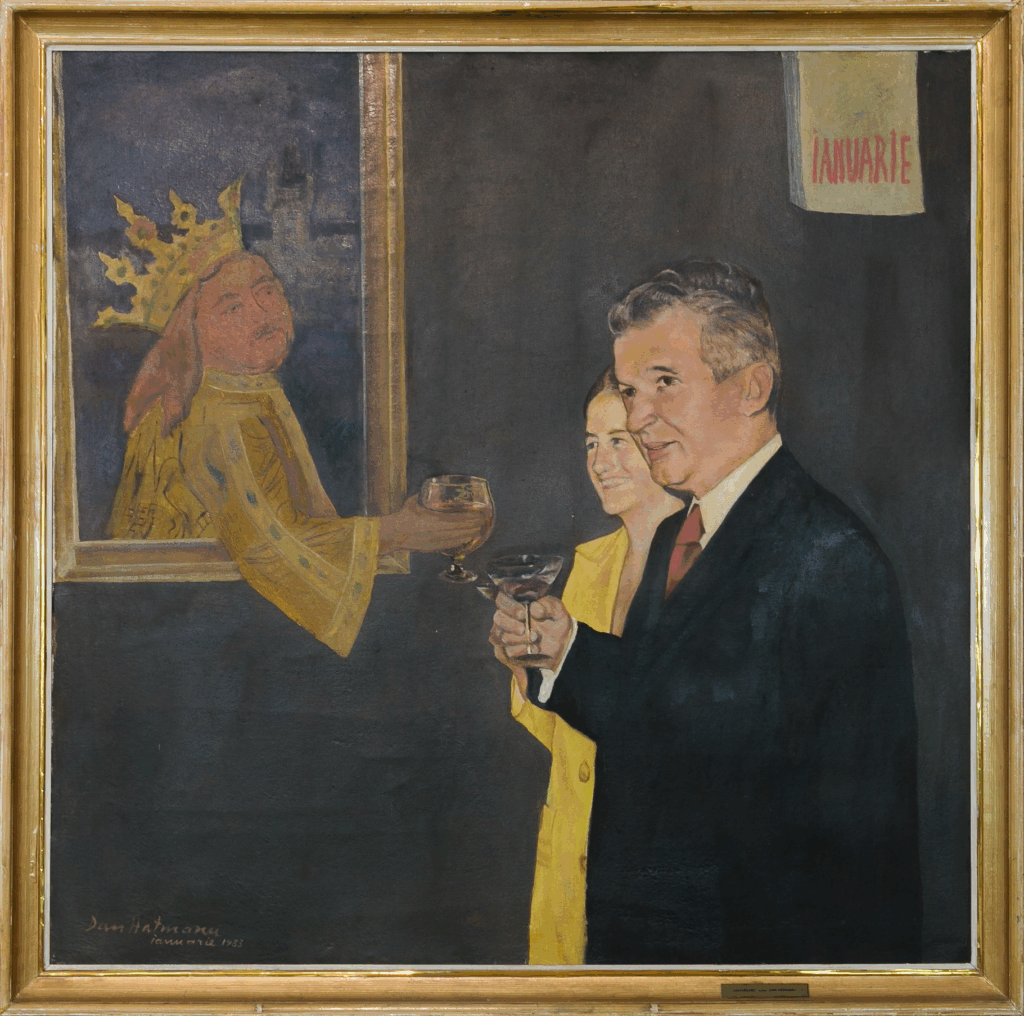

As part of the return to Stalinist-Leninist orthodoxy, doctrines such as socialist realism—long discarded in other Eastern European satellites—were resurrected in Romania, extinguishing the last illusions of cultural liberalization. By reaffirming the Communist Party’s primacy in every domain of cultural life, the general secretary launched a frontal assault on those who sought to keep Romanian culture connected to foreign artistic currents, models, and innovations. Culture and history were now to be depicted as uniquely Romanian, unsullied by influence from either East or West, while the nation itself was cast as a seamless, homogeneous whole—guided across the centuries by strong and wise rulers, with Ceaușescu portrayed as the most recent embodiment of that lineage.

The official line hardened into a state communism drenched in nationalism, laying the foundation for a cult of personality first built around Nicolae Ceaușescu and later expanded to encompass the ruling couple, Nicolae and Elena. Media outlets were tasked with elevating Ceaușescu to near-infallible status. Day after day, the press saturated the public with his image and praises. He became ‘The Genius of the Carpathians,’ ‘The Great Leader,’ ‘Visionary Architect of the Nation,’ among countless other titles. Every issue of Scînteia opened with a glowing front-page story—his meetings, speeches, decrees—bathed in effusive language. The state media extolled him as both brilliant communist theoretician and national savior. Meanwhile, Elena Ceaușescu was cast as Romania’s ‘esteemed scientist’ and ‘Mother of the Nation,’ completing the portrait of a ruling household elevated into myth.

Romanian national-communism occasionally borrowed tropes reminiscent of the interwar fascist movement, particularly in its insistence on autochthonism and resistance to external influences. The regime’s propaganda machine coined the phrase ‘Golden Age’ to describe Ceaușescu’s reign and bestowed upon him the title of ‘Leader’ (Conducător), deliberately echoing the lexicon of Romania’s far-right past. Ceaușescu cast himself as the living embodiment of the nation’s aspirations—the culmination of Romanian history itself, which he claimed to incarnate.

This also marked the apex of Ceaușescu’s effort to construct an all-encompassing propaganda apparatus—one that remained operational even in the regime’s final hours. In 1989, as the Party apparatus, state institutions, and large segments of society turned against him, the newspapers continued to echo official lines, denouncing supposed Western interference in Romania’s internal affairs and portraying the country as a stabilizing force in the region. Even in December 1989, with the dictatorship collapsing, state television aired rallies staged in Ceaușescu’s support—only to have them interrupted by live images of his downfall. Journalists, tightly bound to the Party, had no autonomy; their function was transmission, not inquiry. The very system designed to preserve his rule ended up revealing, in real time, the fragility of a regime built on spectacle.

Related articles: