The following is an adaptation of an article written by Péter Krisztián Zachar, an associate professor and head of department of the Faculty of Public Governance and International Studies of the University of Public Service, originally published on the Governance and Science blog of Ludovika.hu.

Animal Farm Was Published 80 Years Ago

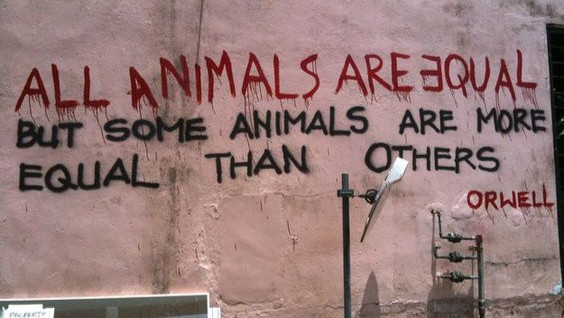

‘All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others.’ Few sentences in literary history express the nature of power more symbolically than these words. This year marks the 80th anniversary of the publication of George Orwell’s cult novella Animal Farm, which at first glance (and according to its subtitle) appears to be a ‘fairy story’, but is in fact a timeless lesson on the workings of political systems, the lure of power, and the logic of corruption. The question remains relevant in 2025: what message does Orwell have for us, eight decades on, about governance and public administration?

Why Is an 80-Year-Old Book Still Relevant Today?

In August 1945, after a lengthy creative process and overcoming legal obstacles and government bans, Animal Farm: A Fairy Story was published, a work Orwell intended as a satire on totalitarian systems, particularly Soviet-style dictatorships. The author wrote about his experiences of the time in a simple yet ingenious allegory that is still relevant today and brought him extraordinary fame: the animals revolt and start a revolution against the humans in order to achieve equality and freedom. But in the end, everything continues as before: a new elite, new privileges, new tyranny.

If we view Orwell’s work solely as a literary work, we easily lose sight of its essence. Animal Farm is a failed socio-political experiment that is as instructive today as it was 80 years ago: how power is transformed, how revolutionary slogans become empty phrases, and how democratic guarantees are dismantled in the absence of institutional checks and balances. Orwell’s story can best be seen as a lesson in power and institutional theory, with serious implications for political science.

Parallels in Governance

The work powerfully illustrates how quickly the idealism of revolution (liberty, equality, fraternity) can vanish into thin air and be replaced by the emergence of a new power elite. In political science, following the similarly radical leftist C Wright Mills, these processes are often described as the power or ruling elite, illustrating that behind the illusion of social equality, a narrow political, economic, and military elite always emerges that monopolizes decision-making. In the novella, the animals originally promise decentralized, horizontal decision-making—direct democracy. But in practice, control gradually falls into the hands of the leaders, and collective control ceases to exist altogether. This issue was described as early as 1911 by sociologist Robert Michels, one of the best-known students of Max Weber and Werner Sombart, as the ‘iron law of oligarchy’. The essence of Michels’ theory is that every complex organization, regardless of how democratic it may be at the outset, will eventually turn into an oligarchy. The reason for this is the problem of oligarchization, that is, that every organization is ultimately controlled by a ruling class, which often takes the form of paid officials, managers, spokespersons, or political strategists who become the dominant players in the organization’s power structures.

One of the most important weapons of Orwell’s era plays a key role in this transformation: propaganda. Just as the manipulation of historical narratives is the main motif of his later novel, 1984, in Animal Farm, we repeatedly see how those in power rewrite the past and control information. Through political communication and framing, slogans are changed and events are given new meanings. The most striking example of this is the gradual change in the rules of the animal farm. The seemingly minor changes in slogans and rules are reframed by those in power and presented as if nothing had changed. The animals’ memories are also constantly questioned—it was never any different, they just ‘remember wrong’—which is one of the classic tools of political communication: rewriting the past to legitimize the present. All this has the power of revelation, even in the age of fake news and disinformation campaigns.

‘One of the most important weapons of Orwell’s era plays a key role in this transformation: propaganda’

And, of course, it raises one of the most important questions: who controls the controllers? The animal revolution begins with the complete dismantling of the old system, without any institutional control. There is no legislature, no constitutional court, no civil control. The result is a rapidly developing totalitarian, authoritarian structure. The work clearly illustrates the typical consequences of a lack of checks and balances. The effectiveness and legitimacy of governance depend not only on the intentions of leaders but also on the system’s ability to self-correct.

Morals Learned — The Lesson Is Still Relevant Today

80 years after its publication, the message of the novella seems to have lost none of its relevance. Among the challenges of modern governance around the world, numerous phenomena remind us of the dynamics described by Orwell. The contemporary equivalent of the cruelly explicit propaganda of the time is social media and algorithmic content filtering. If Snowball and Napoleon were to fight today, they would certainly not use graffiti, but TikTok videos and Facebook posts to battle each other. Public opinion today is shaped not by what happens, but by how events are narrated. This is why one of the key concepts in political science is narrative governance, which appears in textbook form in the dynamics of Animal Farm. The change of elite (the pigs taking the place of the oppressive humans) draws our attention to the fact that corruption is not always caused by ‘bad people’, but stems from the structure of positions of power. The solution is not just a matter of (public) morality, but of institutional design, transparency, and accountability. This echoes what James Madison wrote in his series of essays, The Federalist Papers: ‘If men were angels, no government would be necessary. If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary.’ The rule of law, autonomous institutions, and transparency are not merely theoretical concepts, but safeguards against autocracy.

Based on all this, Animal Farm is not only a timeless literary classic, but also a laboratory of political science and public administration for us, where we can easily observe the mechanisms of power distortion. At the same time, it also points to solutions. Just as Zoltán Magyary’s work made clear on a theoretical level, Orwell uses the tools of literature to illustrate that modern public administration in the post-industrial age can only be successful if, in addition to strong central institutions, the rule of law, transparency, and active civic engagement continuously inspire state leadership to rethink and modernize, resulting in effective, adaptive public administration. If these are lacking, the logic of Animal Farm will play out again and again—not in a fairy story, but in reality.

Related articles:

Click here to read the original article.