Communication has been successfully established with Hunity, the sixth student satellite developed at the Budapest University of Technology and Economics (BME) with support from Hungary’s National Media and Infocommunications Authority (NMHH). The satellite was launched into space on 28 November aboard a SpaceX Falcon rocket from Vandenberg Space Force Base in California.

More than a week after launch was needed to confirm that the satellite’s solar panels were operating correctly and that two-way communication was possible. According to NMHH, the first scientific measurements and datasets are expected in the first half of next year.

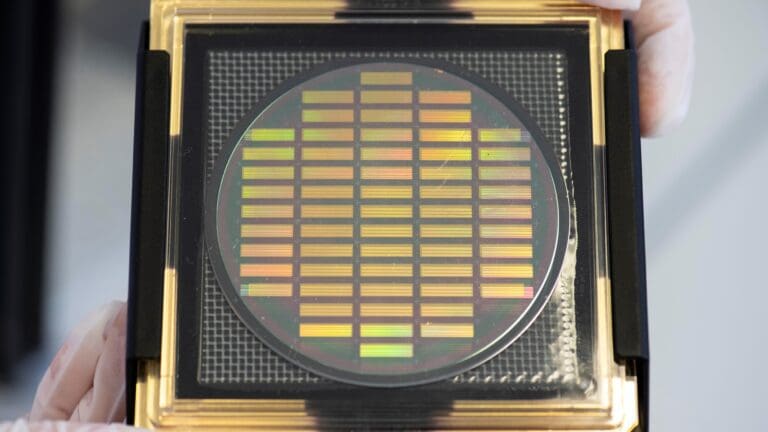

Hunity is a pocket-sized satellite weighing just 868 grams and measuring 5×5×15 centimetres, equipped with deployable solar panels. Despite its size, it carries several instruments designed for scientific experiments. On board are four experimental panels developed by a team from Széchenyi István University in Győr, as well as six panels created by winning teams from last year’s Cansat Hungary secondary school competition.

In the week following launch, engineers systematically tested each module, starting with BME-built pocket qube components, followed by the Cansat transmitters and the university-developed panels. These tests were aimed at determining whether stable contact with the satellite could be achieved at all.

All modules have since been confirmed to be operational, although receiving Hunity’s signals remains a significant technical challenge. As NMHH deputy CEO Péter Vári explained, tracking the satellite is like trying to locate a small brick in space using a flashlight beam, while it races some 400–500 kilometres above Earth at around 27,000 kilometres per hour.

The low-orbit satellite passes over Hungary four times a day, twice in the morning and twice in the evening. Using Kepler orbital data and tracking software, operators prepare for reception as Hunity approaches Europe and rises above the horizon.

Once contact is established, controllers have just 8 to 12 minutes per pass to check system parameters such as battery voltage, temperature conditions and charging performance, and to issue commands determining which onboard modules should be activated.

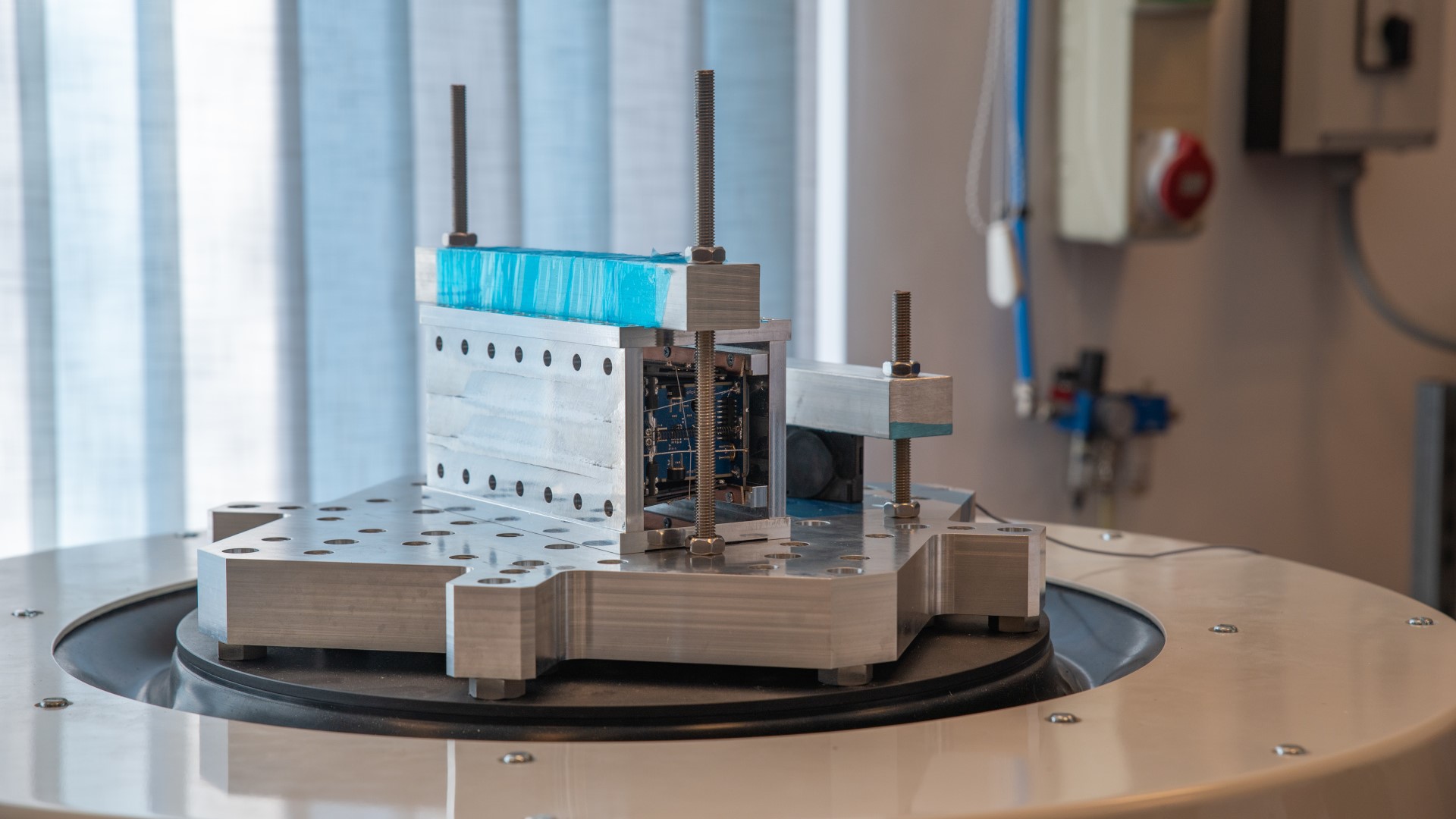

As with all satellites of this type, Hunity has an identical ground-based model used to simulate problems encountered in space. Software issues can often be corrected remotely, but hardware failures cannot, underscoring the importance of extensive pre-launch testing.

Throughout this year, Hunity will undergo in-orbit testing, with routine operations expected to stabilize by year’s end. The first usable measurement results are anticipated in the first half of next year.

The inclusion of modules developed by secondary school students is seen as particularly significant, giving young participants rare hands-on experience of conducting experiments in space. For Hungarian students, this represents a unique scientific reference point that could support future research achievements.

NMHH previously supported the SMOG-1 satellite mission, which mapped electromagnetic smog emitted from Earth into space, producing globally unique data. Those measurements have already helped assess how much energy is lost through various radio systems and mobile networks.

Related articles: