UPDATE: Minister of Foreign Affairs Péter Szijjártó addressed the issue at an unrelated press conference on 1 September, after our article was first published. Responding to a reporter’s question, he said:

‘Everyone must respect the history of Hungary, the Hungarian people, and the Hungarian people’s desire for freedom. 1956…is one of the most glorious moments in Hungarian history, when the Hungarian people gave their lives for their freedom and the country’s sovereignty…Therefore, we are not even willing to discuss this issue…Every Hungarian person who stood up for Hungary’s freedom at that time is a hero. We deplore and and reject any readings to the contrary.’

A new Russian history textbook for 11th graders is causing outrage in Hungary—and rightly so. The cause of the indignation are the sections of the new schoolbook describing the events of 1956. The textbook was called out by public figures on both the Hungarian left and right. Conservative historian Áron Máthé, vice-chair of the Committee of National Remembrance (Nemzeti Emlékezet Bizottsága, NEB) declared that it is a ‘falsification of history’, while professor, historian and Russia expert Zoltán Sz. Bíró also strictly objected to the claims of the textbook and called for the government to condemn the text. Many leading opposition politicians, including Budapest Mayor Gergely Karácsony, have also been vocal in condemning both the textbook and the Orbán administration for not denouncing it publicly.

In the over 400 pages long schoolbook there are 36 mentions of ’Hungary’ or ’Hungarians’, most of the time together with other nations in East-Central Europe. So it needs to be clarified that the interpretation of Hungarian history is not a priority of the book.

Although there is little overall attention paid to the country, the few paragraphs that are about Hungarian history have sparked widespread public discontent in Hungary. What the authors of the text on 1956 wrote demonstrates that the view of 1956 in official Russia is still fundamentally different from the Hungarian interpretation

and, for that matter, from objective reality.

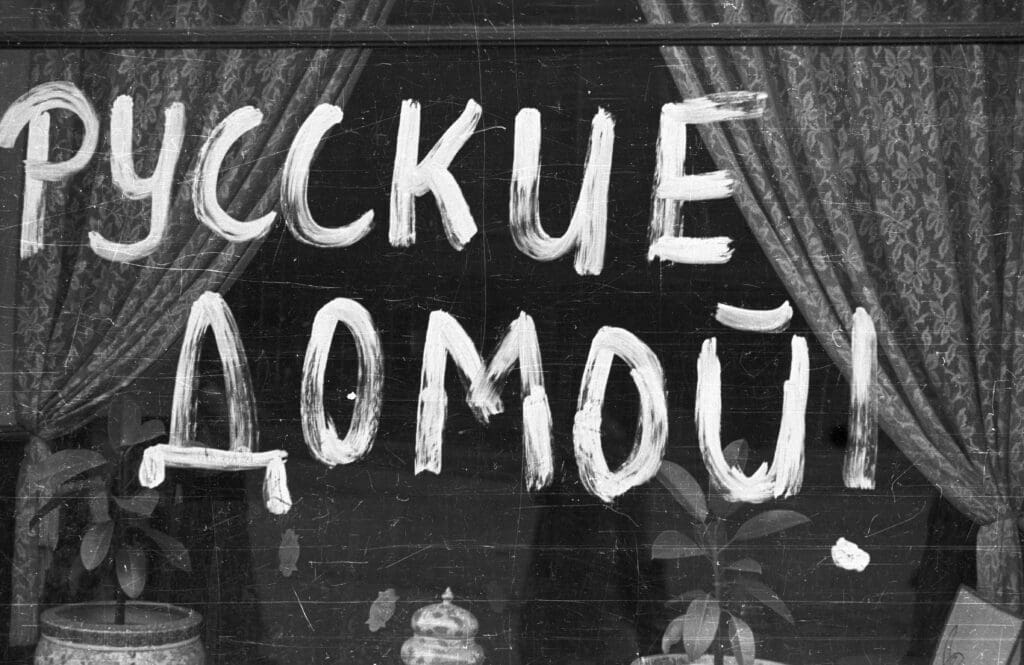

It is worth quoting the text in question in its entirety. Next to a picture of the destroyed Stalin statue of Budapest, it reads as follows (page 130 of the Russian history schoolbook for class 11 by V. R. Medinsky, a Putin advisor, and A. V. Torkunov; bold used for emphasis):

‘A demolished statue of Stalin in Budapest. Hungary. 1956.

The rebelling radicals, among whom there were many former soldiers of the armed forces of fascist Hungary, were characterized during the uprising not only by the vandalism they committed against Soviet monuments and symbols, but also by the numerous murders of representatives of the Hungarian Workers’ Party, employees of law enforcement agencies and members of their families. Even conscripted soldiers guarding government buildings became victims of the brutal massacres.’

After this short description of the revolution, the textbook recommends students to think about the following question: ‘May the criticism of Stalin’s personality cult in the USSR have been the reason for the outbreak of events in Hungary in 1956?’

Later on, the text continues with the following sentences: ‘The protesters criticized the Hungarian leadership and its pro-Soviet orientation, demanding Hungary’s withdrawal from the Warsaw Pact. With good reasons to assume that the catalyst for the Hungarian crisis were the actions of the Western intelligence services and the internal opposition they supported, the USSR sent troops into Hungary and helped the Hungarian authorities suppress the uprising.’

Quite clearly, this interpretation of 1956 intentionally represents the revolution and freedom fight in an unjustifiably negative light. Let’s look at the gravest issues with the textbook one by one.

First of all, the Russian schoolbook fails to call the events a ’revolution’ and settles for the word ‘uprising’. 1956 was a revolution and calling it that way also carries a real meaning in Hungary—the first time 1956 was called a revolution in public was one of the achievements of the 1989 democratization, which broke all the taboos and the censorship of the state socialist regime.

Else than the terminology in use, the Russian textbook also radically misrepresents the events that happened in October–November 1956. The revolution was a heroic struggle for freedom, whereas the Russian textbook characterises it as a massacre of the representatives of a legitimate authority. Hungary does not accept that the state socialist regime was legitimate: in fact, the Hungarian Fundamental Law states that Hungary was not a sovereign state under the Communist rule, the representatives of which had not been freely elected but imposed on the country.

Furthermore, contrary to what the textbook suggests, it was not the revolutionaries but the Communist state that committed a massacre in 1956. On 25 October, known as the ‘bloody Thursday’, at least 200 peacefully demonstrating people, including women and children, were shot dead by still unidentified perpetrators (but undoubtedly acting on behalf of the regime) in front of Hungary’s Parliament. Not to mention the fact that the entire revolution was definitely not characterised by arbitrary and excessive bloodshed. 1956 was unquestionably a people’s fight for freedom against an oppressive, illegitimate regime and their foreign enablers, the Soviets.

The text caused a stir in Hungary especially as it considerably diverges from the position Russia (and Putin himself) took a couple of years ago. While the above-described narrative is similar to the one of the USSR’s, a couple of years ago, the Russian President seemed to have accepted a different understanding of 1956 that was closer to the Hungarian one. In 2006, on the 50th anniversary of the Revolution and Freedom Fight,

Putin placed a wreath at a memorial dedicated to the heroes of the revolution

and admitted that Russians feel a ‘moral responsibility’ for the crushing of 1956. While in 2006, the official Russian and Hungarian understandings of 1956 were as close as never before, by 2016, the narratives grew apart again. As Hungarian Conservative has noted, on the 60th anniversary of the revolution, Russian state television presented 1956 as a product of agitation by the CIA (a claim unfounded by historiographic research) and called it a ‘fascist counterrevolution’.

The Russian official narrative has thus been echoing the Communist propaganda of the Soviet times ever since 2016, and the recently published textbook is also a reiteration of this same stance. It seems to be the case that Russia is still unable to come to terms with the sins of its Soviet past.

The 2016 controversy was further worsened by an interview with Socialist Party politician Szófia Havas, whose father was killed by the revolutionaries in 1956, and therefore was willing to go along with the Russian narrative about the uprising and

defamed 1956 in the pro-Kremlin media.

Her words and the television programme led a to a major diplomatic rift and caused consternation even inside the Socialist Party, of which Havas was soon forced out.

While this most recent chapter of the hostile interpretations of 1956 is still unfolding, on Wednesday evening the Russian Embassy in Budapest responded to critiques in a Facebook post. The post highlighted that there are complex issues in the two countries’ shared history that must be approached carefully. The embassy expressed its disappointment that the Hungarian media based its reports about the textbook on a Latvia-based Russian language site Meduza. While the news website is widely considered to be reliable in the West, it is labelled a ‘foreign agent’ by Moscow. The embassy also stressed that the Russian media has reported on ten different versions of the same book and it is not sure which version the Hungarian media is criticizing. The embassy even claimed that as of Wednesday, it does not possess the final version of the book, so they are unable to clear up the uncertainty. Finally, the post also added that the versions the embassy has seen do not call the revolution ‘fascist’.

Related articles: