This article was published in Vol. 4 No. 1 of our print edition.

The outbreak of the war in Ukraine in 2022 kicked down the door on Hungarian public opinion, confronting it with the chilly reality that—although global politics is a game for the big boys—if we fail to take ourselves seriously and choose instead to simply go with the flow, we might easily find ourselves with the short end of the stick. At Transit Festival last August, when we sat down to discuss the phenomenon, the editor of Kommentár called it a ‘global regime change’,1 and we all agreed that being part of the Western alliance did provide Hungary with protection, but that we needed to remain alert and flexible to prevent the ship of the Hungarian state from being capsized by an unexpected storm.

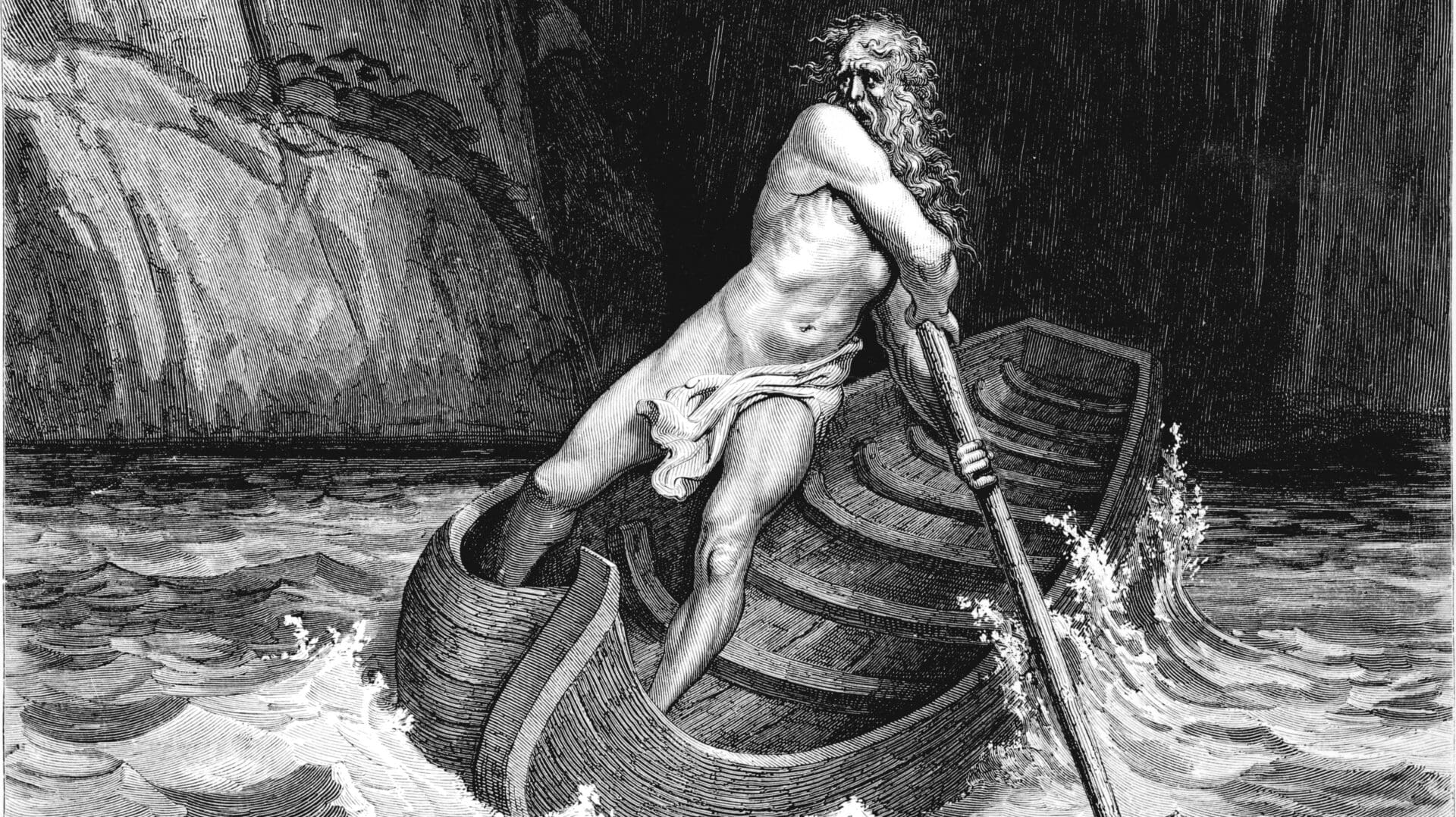

The latest front of the great reshuffling seems to have been opened in the Middle East, while in the streets of major Western cities, members of terrorist cells, reared on decades of painstakingly nurtured indoctrination, continue to roam free. We must find our bearings in a new landscape, where the old rules no longer necessarily apply. The United States has been lured into a classic trap of overexpansion by its challengers and its own ideology of hegemony. Meanwhile, the European Union seems to be bogged down in a downward spiral of self-liquidation. These days, more pressingly than before, we are forced to steer between Scylla and Charybdis, even as we heed Pompey’s admonition: Navigare necesse est.

The New Alignment

On 15 November 2020, as the world anxiously watched the latest reports on COVID casualties, fifteen states held a zoom meeting which concluded with the creation of the largest free trade bloc in history. The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP)2 may have an innocuous enough name, but it is formidable in terms of sheer numbers, marshalling nearly one third of the global population and GDP. More to the point from our perspective, this treaty among Asian states both highly and moderately developed has been signed not only by China but also by a number of states considered to be ‘liberal democracies’ from a Western perspective (Australia, New Zealand, Japan, and South Korea) or at least ‘friendly with the West’ (Vietnam and the Philippines). Symbolically, the RCEP came into being after the demise of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) announced by Barack Obama, when Donald Trump—fearful of a continuing loss of American jobs—withdrew, allowing China to fill the void. This left no choice for the others but to adapt to the new situation, even if they happened to be Western in the cultural sense, such as Australia, a member of the Anglo-Saxon defensive alliance AUKUS and the Five Eyes intelligence agreement (this along with New Zealand). The well-known geopolitical stress endemic to Japanese–Chinese relations could not prevent this, nor could the shield mounted by nearly 30,000 US troops in the defence of the bastion of the global electronics industry (and K-pop) against the whims of the Kim dynasty. The interested parties did the maths and realized the need to strike a feasible balance in the new international situation, despite their special allegiances to the United States.3

The truly unique player in this new alignment is India, which decided not to join the RCEP, nor even to try to find a balance. As what is now the world’s most populous country, boasting one of its most ancient civilizations, India has every right to think of itself as a point of reference in and of itself, rather than as a nation that must look for reference points elsewhere. It has been contesting with China for control over a territory the size of Hungary in the Himalayas and, as a member of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (QSD or, popularly, the Quad),4 is a key state for maritime routes and the budding American-led alliance aimed to counter the Chinese–Russian axis in Eurasia. By contrast, India is also a founder of BRICS, as well as one of the largest customers of sanctioned Russian energy, not to mention having been tied up in a mutual economic dependency with China. No wonder that Beijing would hate to see India moored among hostile vessels. In any case, this process is being slowed down by human rights concerns from Washington and by the fact that Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has recently accused the government of India of endorsing a politically motivated assassination.5

Speaking of BRICS, it is worth taking a look at Saudi Arabia, one of the latest countries to join the bloc created with the aim of dismantling the Western world order. Mohammed bin Salman, the de facto ruler of Saudi Arabia—which the Biden administration described as ‘a pariah’ state in the aftermath of the admittedly scandalous murder and dismemberment of a dissenting journalist at the Saudi consulate in Istanbul—has not missed a single opportunity to annoy Biden. Weighing more heavily in the balance than these high emotions, however, are the vested interests of Saudi Arabia, which favour high crude prices and thus cooperation with Moscow, despite American pressure to the contrary, and call for the ready availability of a powerful patron with the ability to keep Iran at bay. With China now the largest importer of Saudi oil, Riyadh has reason to court Beijing and is aware of the possibility of exerting pressure on Washington by doing so. The Arabian Peninsula does have the potential to become a major transit corridor, and the Saudis want to profit from the rivalry over it between China and the United States. China managed to put one foot in the door by ostensibly forging reconciliation between Iran and Saudi Arabia, setting off alarm bells in Washington. Biden responded promptly by announcing plans for a South Asian infrastructure corridor to be financed in part by the United States,6 and, sweeping the dismemberment incident under the carpet, began to bargain with Saudi Arabia over its wish list—including its own nuclear programme, security safeguards, and more arms.

In other words, Washington warmed up Trump’s project by offering incentives to Riyadh in return for Saudi efforts to normalize relations with Israel, another US ally. The completion of the American–Israeli–Saudi triangle is a nightmare for Tehran, the prevention of which may have loomed large behind the devastating strike on Israel by Hamas in October 2023—an offensive that has not only shocked the world in its sheer scale but provided it with plenty of food for thought. The operation was supposed to trigger a regional war. There is but a single sense in which America’s return to the Middle East could serve Russia and China: by diverting attention and resources from Ukraine and the Far East to a bloody and chaotic conflict unfolding in the Levant. In this new international situation, hanging on to old clients is more cumbersome than ever, winning new partners more difficult, and keeping opponents in check increasingly perilous.

The Pitfalls of Liberal Internationalism

Wishful thinking in the United States has long regarded China as capable of being pigeonholed in an international order governed by rules, meaning that it would conform to US notions of power hierarchy. China, however, while evolving into the manufacturing centre of the world, defied all expectations by not becoming an open society. In fact, China turned out to have interests of its own which could conflict with those of Washington. After a while, the technological revolution delivered us a kind of ‘Sputnik moment’ familiar from the American–Russian space race, waking the United States to its vulnerability. While the America of the 1960s managed to clinch the initiative against a clay-footed Soviet Union, the times have changed. Today, Silicon Valley, the new Menlo Park, Google, and OpenAI serve as latter-day Edisons, but China stands a good chance of taking the lead in the industrial application of the inventions they manufacture. The copying and further development of technology in a cut-throat Confucian in-house competition, coupled with formidable databases and state control, has resulted in the rise of new titans who may well end up snatching the trophy from the original innovators’ hands.7

The struggle between the United States and China, waged on many fronts, is now focused on the Taiwan Strait. The Island of Taiwan is the Achilles heel of Chinese nationalism, the place to close the narrative circle of the ‘hundred years of humiliation’, from the Opium Wars (1839–1860) to the declaration of the People’s Republic of China in October 1949. At the same time, it is a key lynchpin in the strategic belt with which China believes the United States seeks to confine the ‘Celestial Empire’. It is here where China, awaiting an opportune moment, wishes to put a wedge into the US hegemony over the world’s seas. Even in Washington’s estimation, China is now capable of inflicting heavy damage on the forward fleet of US vessels in the line of the ‘first island chain’, which includes Taiwan.8 Neither a Pyrrhic victory protecting Taiwan nor giving up on the island altogether would be an acceptable scenario for the United States. It is common to trace Chinese strategy to the logic of encircling the opponent known from the game Go. By contrast, the West plays chess and aims for the queen. Does this mean that the United States will execute a pre-emptive strike, before China spirals out of control? Or is it Beijing that will avoid being encircled by luring the marines into a trap?

‘These days, more pressingly than before, we are forced to steer between Scylla and Charybdis, even as we heed Pompey’s admonition: Navigare necesse est’

Nobody knows. In any event, history hardly supplies any examples of a major power surrendering supremacy without putting up a fight. For at least a decade now, the United States has been trying to find a grip on its challenger, but Trump was the first to come out and say that the ‘one-size-fits-all’ logic of liberal internationalism was no longer able to maintain the status quo. What must be done instead is to mitigate the dangers of overexpansion by phasing out secondary liabilities in order to concentrate on the main challenger. This is why Trump withdrew from various trade treaties, wanted to get out of the Middle East, initiated a debate on sharing burdens among NATO members, and, finally, launched a tariff war against China.

It remains doubtful whether a more mature version of Trump’s concept—assuming he is not thwarted by the ‘deep state’, and assuming he wins a second presidential term—would have much chance of reversing the loss of ground. However, following on the heels of Trump’s experiment, Biden’s cabinet returned to the recipe of democracies versus autocracies, with ingredients well past their sell-by date. As Kissinger put it, winning the Cold War lured the United States into the illusion that it could ignore flexibility in real-world politics, and it would suffice to rely on disseminating its own view of justice, since progress was inevitably attendant on an international order obeying certain rules.9 Yet liberal internationalism is not an ideology so much as a platform straddling various fields from the economy to culture and media, which lays out a broad highway for the march of lobbies intertwined with American foreign policy. Of course, the various interest groups active in business, politics, defence, and intelligence detest China as much as Trump does, but they are hesitant to give up their positions and retreat to ‘Fortress America’, unless they have to, as they did in Afghanistan. Indeed, they seek to expand while and where they can. So, undoubtedly does BlackRock which, like an East India Company transposed to the 21st century, is bent on gaining stewardship over Ukraine, financing its efforts mainly with funds provided by Western taxpayers funnelled through Kyiv.10

The current Democratic administration spearheaded by Biden shows to the outside world a face of the deep state that is remarkable in its almost Chernenko-like rosiness. That Russia has perpetrated an act of aggression on Ukraine and its responsibility for the war is beyond doubt. The road to that war, however, was paved with insolvent promises of NATO membership; with the prospect of more portions of the Ukrainian economy being engulfed by US interest groups, including the embarrassingly direct involvement of the Biden family; and with the ideology which established its ‘model state’ on the eastern fringes of Europe by manipulating Ukrainian nationalism and co-opting some of its constituent elements. The Americans were confident that the Russians would stomach it all, while the Russians believed that this house of cards would crumble under their offensive in a matter of days. The results are well known.

In this war, the United States has been committing massive resources to fighting a Russia whose intrinsic weaknesses, as now stands clearly revealed, prevent it from posing a conventional military threat to NATO, but which cannot be vanquished either in the conventional sense of that word. Moreover, common sense alone should warn against forcing a state in possession of six thousand nuclear warheads to the brink of collapse. Indeed, this war—fought without realistic military and political objectives on the part of the West—exhausts the definition of ‘quagmire’. Sinking ever deeper into this dreaded swamp, the decision-makers continue to raise the stakes, driving themselves into a classic case of ‘dollar auction’, to borrow a term from game theory.

If we look for a master plan in all this, and regard the exemplary punishment of the instigators of the conflict as its main goal, even the new miracle drug known as ‘decoupling’ will seem to have failed to produce promising results. Peeking out of our bubble of opinion, we discern disconcertingly few non-NATO and non-EU partner countries embracing the comprehensive sanctions imposed on Russia. Apart from Japan, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand, virtually no other state has joined the initiative, not even Türkiye, despite being a member of NATO. On the other hand, the war has precipitated certain processes. It has tightened the rapport between the opponents of the West, helping to solidify the alliance between Russia and China and even to swell its ranks by new members such as Iran and North Korea. The financial sanctions, along with the SWIFT prohibition imposed on Russia, have given fresh impetus to the construction of accounting regimes divorced from those of the West. The freezing of dollar-based assets also undermines the position of green currency reserves, as no one wants to become vulnerable to blackmail. Most of Russia’s sanction-strapped energy and resources have found markets in the rest of the world, and the hundred-dollar price of oil demonstrates the weakness of the West rather than its power. India, Saudi Arabia, and the rest of the bunch are now independent players no longer willing to bow to pressure from the United States, let alone from Europe, as they used to thirty years ago. The machine of decoupling seems to be stalling just as badly when deployed against China, which the West, for now, is trying to sideline by more prudent methods. The export ceilings on the most advanced technologies and other prohibitive schemes enforced against investment have hit a raw nerve but also accelerated the shift to self-sufficiency, while countermeasures on the trade in rare earth metals have sent global markets into a dizzy upward spiral. For the time being, the strategy of ‘friendshoring’ (that is, the relocation of supply chains to friendly countries) seems to have put those very friends in a vulnerable position after it turned out to be virtually impossible to sidestep China in these supply chains. While the statistical indices of American–Chinese trade did see a setback on paper, Mexico and Vietnam posted significantly higher exports from China.11

The Western institutions that used to be the heartbeat of the world are no longer impossible to circumvent today. Even as decoupling does cause headaches to the system’s detractors, attempts to enforce the dogma of internationalism at all costs will inevitably accelerate the process whereby the West loses ground. If this be the master plan of the United States, the only serious achievement it has to show for itself thus far is to have brought Europe to its knees.

Europe as Queen Sacrifice

In the wake of the Second World War, the United States offered the Western half of Europe, deprived of its imperial laurels, physical security through NATO and economic recovery through the Marshall Plan. In part, these projects were motivated by selfish interests, insofar as strengthening Europe’s influence meant stability. For the same reason, Washington supported the integration process, but never with the aim of rekindling the Old Continent as an independent fulcrum of power in its own right. The daydreams of foreign policy entertained by Europe during the 1990s were quickly squashed by the Yugoslav crisis and the ensuing Pax Americana in the Balkans which haunt the EU to this day. The euro failed to mount a credible challenge to the dollar, and the financial meltdown of 2008 made it clear that Europe would never have a say in the contest between the United States and China.

Despite the internal strife, a delicate political balance persisted on the major issues defining the operation of Europe’s economic machinery, including Russian relations. Here, the Polish–Baltic axis adopted a massively sceptical stance due to very legitimate, historically proven concerns over security, but this did little to prevent equally legitimate considerations of competitiveness from being vindicated in the energy sector. Then, ideology began to supplant common sense. A political frenzy nourished by natural disasters (the nuclear accident in Fukushima among them) and various campaigns built on cleverly devised narratives (e.g. the diesel emissions scandal) began to tweak the balance. Germany declared war on nuclear energy while simultaneously pushing for the electrification of the automotive industry. Exploiting the wave of migration that flooded Europe starting in 2015, and then the gender issue imported for this express purpose, an aggressive sect announced a cultural revolution, an experiment of irreversibly reforming European societies. The levees gave way when the Ukrainian War broke out, with the EU winding up its economic ties to Russia in a matter of months. At the same time, the war—or, more precisely, the ‘struggle between democracies and autocracies’—emboldened the West to ‘lecture’ China—an enterprise that has been pursued with equal determination, if less hurriedly of late.12

Searching for the source of these seemingly unrelated processes, it is difficult not to start with the intellectual, commercial, and political coterie of American Democrats. Plans for the American integration of Europe had long been on their table,13 and the war stirred just the perfect storm in the guise of which to enmesh an EU that had lost its clout and will to act on its own. Australia, Japan, and South Korea adopted the sanctions against Russia only because they were relatively painless for them. By contrast, the sanctions on Russia for Europe—a region heavily dependent on Russian energy—amount to a burden of equivalent magnitude as if America’s allies in Asia froze their relations with China. Indeed, this possibility cannot be ruled out. But while the United States is under pressure to spend more and more on purchasing loyalty, the political elite of Europe turns a blind eye to the blowing up of Nord Stream, in dumb acquiescence. Nor does Europe seem to mobilize any meaningful effort or resources to counter the American Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), which explicitly threatens to drain European industry by means of government subsidies.14

Going against the grain of all European norms, the main priority of the EU budget is now to finance the Russian–American war waged on Ukrainian soil. Moreover, it has become the top priority not only of the common budget but of common policy, as exemplified by the European Commission’s position versus the member states in the case of Ukrainian grain dumping. Finally, seeing the aggressive political and media campaigns for Ukraine’s membership in the EU, it is no exaggeration to say that the ‘cause of Ukraine’ has been turned into a tool of legitimizing the very existence of EU institutions.

Ukraine is indeed fighting a war of national defence and is a victim of Russian aggression. The ‘cause of Ukraine’, however, has assumed a life of its own. Calcified as an ideology, it has been subsumed in the canon of liberal internationalism, which permits no response other than one of enthusiastic approval. The fatigue-clad Zelenskyy has become our Fidel Castro of the day, the symbol of (popular) democratic solidarity pitted against any autocracy. The ruling political and institutional elite of Europe, left without independent ideas of their own following the demise of the great generations in the political profession, have subscribed to this canon—whether out of conviction or just going with the flow or bowing to incentives—and wilfully acknowledges Europe’s degradation to the status of a simple client of the United States. Historically, the pioneers of this transformation were the useful idiots of the Soviets during the ‘anti-war’ movements of the 1980s—in fact, anti-American movements financed by the KGB. Nowadays, the current generation of this faction has found employment as a support team in the service of American Democrats, who bear more than a passing resemblance to the former overlords of the Soviet Union in their parlance and intolerance. This group perceives in the ‘cause of Ukraine’ a window of opportunity to remodel the EU with a view to inserting it in the world order commandeered by American Democrats. Even appearances no longer count. This is how the disbursement of funds to Hungary to which it is entitled came to be made contingent upon Hungary’s toeing the line regarding Ukraine, and this is how Poland, long the most devoted supporter of Ukraine, came to be labelled by the Financial Times a ‘rogue state’ over its resolve to stand up for its national interests in the grain issue.15 The Vilnius Summit made it abundantly clear that the United States had for the moment no intention of sparking a world war by accepting Ukraine in the fold of NATO. This leaves the EU in charge of this task, demoted as it is to the status of a subservient client. Pending membership in the outcome of the process, Ukraine (or a rump Ukraine remaining) would then uphold US interests. In addition, the enlargement would finally force the implementation of ‘institutional reforms’, such as the abolition of the individual nation states’ veto rights, for which the revolutionaries have long been clamouring in order to crush dissent and establish the federalist utopia. This, ultimately, is what is really at stake in the debate over Ukraine’s NATO membership.

Which Way from Here, Hungary?

For thirteen years now, Hungary’s strategy has been straightforward and steadfast in pursuing integration within the EU’s unified market and attracting the largest possible volume of investment in order to boost the country’s competitiveness. While this objective indispensably presupposes access to the Union’s markets, the increasingly less Western face of globalization means that, in our view, our competitiveness cannot be enhanced except by forging bridges between East and West. For the reasons discussed above, however, European institutions tend in the opposite direction, that of turning in on themselves. When something like this happens, one must always ask the question: Who is really driving the wrong way, us or all the oncoming traffic? Is there an alternative to what we are doing?

Theoretically, after all, we would be free to follow Poland’s strategy. Warsaw is putting all its eggs in one basket by seeking to clinch the role of a sort of outpost of Washington, tasked with keeping both Russia and Germany in check, even as it tries to ‘stay clear’ of the excesses of Woke foreign policy. As a middle-sized power of a country with a population of 40 million, the Poles are right to think that all this makes sense from their perspective. The only question is whether Washington is contemplating reserving this role, or at least part of it, for Ukraine rather than Poland. Which of the two is the more convenient candidate for Washington? Poland, prioritizing its own national interests, or Ukraine, subsisting on the life support system of BlackRock? Also, is this strategy truly well founded economically? The figures tell us that the structure of foreign capital investment in Poland is not much different from that in Hungary. While the United States ranks respectably high on the list, the market is essentially dominated by Germany and other European countries.16 As for the US policy of industry development (or, rather, repatriation), its drift is hardly toward some massive expansion in Europe, as the example of IRA perfectly illustrates.

Beyond leaving these questions open, Hungary’s size and geographical situation also seem to favour perseverance in our recent strategy as we strive to maximize our manoeuvring space while we can. It is not known, however, how long the unified internal market of the EU, the pillar of this strategy of ours, is going to survive. The push for the integration of Ukraine, in the absence of the requisite consensus, may provide an impetus to the proposal of a (for now) multi-speed EU. If those missing out on a tighter integration, including Hungary, manage (or are allowed) to remain part of the unified market, we could hang on to the main advantage of membership and thus to our resilience, while leaving ideological conformism to the vanguard, enabling them to turn their utopistic dream of federalism into reality, along with all the achievements of their culture war.

That said, the question that looms even larger now is whether the unified internal market can remain functional at all in the mid-term if the current trends continue. The European recession does not seem to be boom-driven. In fact, what is transpiring before our eyes is the accelerating decline of a Europe decoupled from its traditional sources of cheap (or relatively cheap) energy, as well as from its markets and investors, while rapidly winding up its industrial capacities. The appearance of democratic legitimation may still be maintained for a while, but tensions within individual member states are set to escalate. The societies of Western Europe, culturally splintered by an enduring economic setback, may soon become prey to conditions akin to a ticking bomb. Sooner or later, these conditions will paralyze the common institutions. Under the weight of the intrinsic and extrinsic contradictions of the neo-communist experiment, the EU may eventually collapse altogether, in much the same way that the Soviet Union met its demise.

If this comes to pass, the member states or their groups, recovering from the initial shock, may reclaim powers currently shared across the EU, at first provisionally, and later perhaps on a permanent basis—as Central Europe will possibly do. In the ensuing chaos engulfing the continent, much will depend on the ability of each state to remain functional and ready to adapt to the new situation. As opposed to the European mainstream, which proclaims multiculturalism but in reality wraps itself up in cultural arrogance, Hungary’s openness and pragmatic stance towards the seven eighths of the world that is outside the Western realm already confer an advantage upon us. If the framework of the world as we know it crumbles against our will, this cultural openness of ours may well supply the footing for us from which to enter the next period with confidence. For navigare necesse est—Sail we must.

NOTES

1 Márton Békés, ‘Világrendszerváltás’ (Global Regime Change), Kommentár, 4 (2022), www.xxiszazadintezet.hu/vilagrendszervaltas/.

2 Members include Australia, Brunei, Cambodia, China, Indonesia, Japan, South Korea, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, New Zealand, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam.

3 As the New Zealand government’s website puts it, ‘The RCEP anchors New Zealand in a region that is the Engine room of the global economy’, www.mfat.govt.nz/en/trade/free-trade-agreements/free-trade-agreements-in-force/regional-comprehensive-economic-partnership-rcep/rcep-overview, accessed 25 January 2024.

4 The QUAD signatories are the United States, Japan, Australia, and India.

5 ‘Justin Trudeau Repeats Allegation against India amid Row’, BBC News (22 September 2023), www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-66886559.

6 Barak Ravid, ‘Biden Unveils Infrastructure Project to Connect India, Middle East and Europe’, Axios (9 September 2023), www.axios.com/2023/09/09/us-saudi-india-uae-railway-deal-middle-east-europe.

7 Kai-Fu Lee, AI Superpowers: China, Silicon Valley, and the New World Order (Harper Business, 2018).

8 ‘How the Pentagon Thinks about America’s Strategy in the Pacific’, The Economist (15 June 2023), www.economist.com/united-states/2023/06/15/how-the-pentagon-thinks-about-americas-strategy-in-the-pacific.

9 Henry Kissinger, Leadership: Six Studies in World Strategy (Allen Lane, 2022), 201.

10 According to the deal between BlackRock and the Ukrainian government, the company is in charge of ‘coordinating investment efforts to rebuild the war-torn nation’. The world’s largest investment advisory firm exists in a virtually symbiotic relationship with the Biden administration, with half a dozen of its top managers drawn from among current government officials, and several members of the board having formerly served as Obama’s senior staff. For more on the subject: Juan Angel Soto, ‘BlackRock, Ukraine and the Davos Gang’, The European Conservative (26 January 2023), https://europeanconservative.com/articles/commentary/blackrock-ukraine-and-the-davos-gang/.

11 ‘What Is Friendshoring?’, The Economist (30 August 2023), www.economist.com/the-economist-explains/2023/08/30/what-is-friendshoring.

12 Stuart Lau, ‘Brussels Trade Chief Warns China and EU Could Drift Apart over Putin’s War’, Politico (26 September 2023), www.politico.eu/newsletter/china-watcher/brussels-trade-chief-warns-china-and-eu-could-drift-apart-over-putins-war/.

13 Under Obama, the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) was supposed to serve to integrate the Old Continent.

14 Ajit Niranjan, ‘We Are Facing Dependence on China’, The Guardian (16 August 2023), www.theguardian. com/world/2023/aug/16/facing-dependence-on-china-eu-battles-to-support-green-industry.

15 Allan Beattie, ‘The EU Has a Rogue State Problem’, Financial Times (19 September 2023), www.ft.com/content/0319bf9e-0feb-44a4-8724-1471b80f91ae.

16 AmCham Poland Quarterly, 6/3 (2023).

Related articles: