What approach should Christians take to modern politics? What are their obligations in contemporary public life? Which Christian values should be endorsed in modern democracy and which political instruments are permitted while doing so? Several Christian philosophers, theologians, and politicians have in the past sought to provide answers to these crucial questions. Our series of articles intends to rekindle interest in those authors, firstly because we believe that these authors receive less attention than they deserve, and without forgetting the extensive academic literature on them (since most of them attract serious scholarly interest) we argue that their ideas are underrepresented in public discourse. Secondly, we believe that to answer the questions raised above, one should be able to study acknowledged theologians and philosophers who are well-versed in the wisdom of the Christian faith and base their political arguments on it. Consequently, the political insights of modern theologians will be presented with a special focus on the Christian origins and sources of their ideas. We hope that these articles will increase public interest in these inspiring figures.

Our article series have already elaborated on several Catholic and Protestant authors, including Abraham Kuyper, Reinhold Niebuhr, Joseph Ratzinger, Johann Baptist Metz, Ernst-Wolfgang Böckenförde, Helmut Richard Niebuhr, Walter Rauschenbusch, Erik Peterson and John Coleman Bennett.

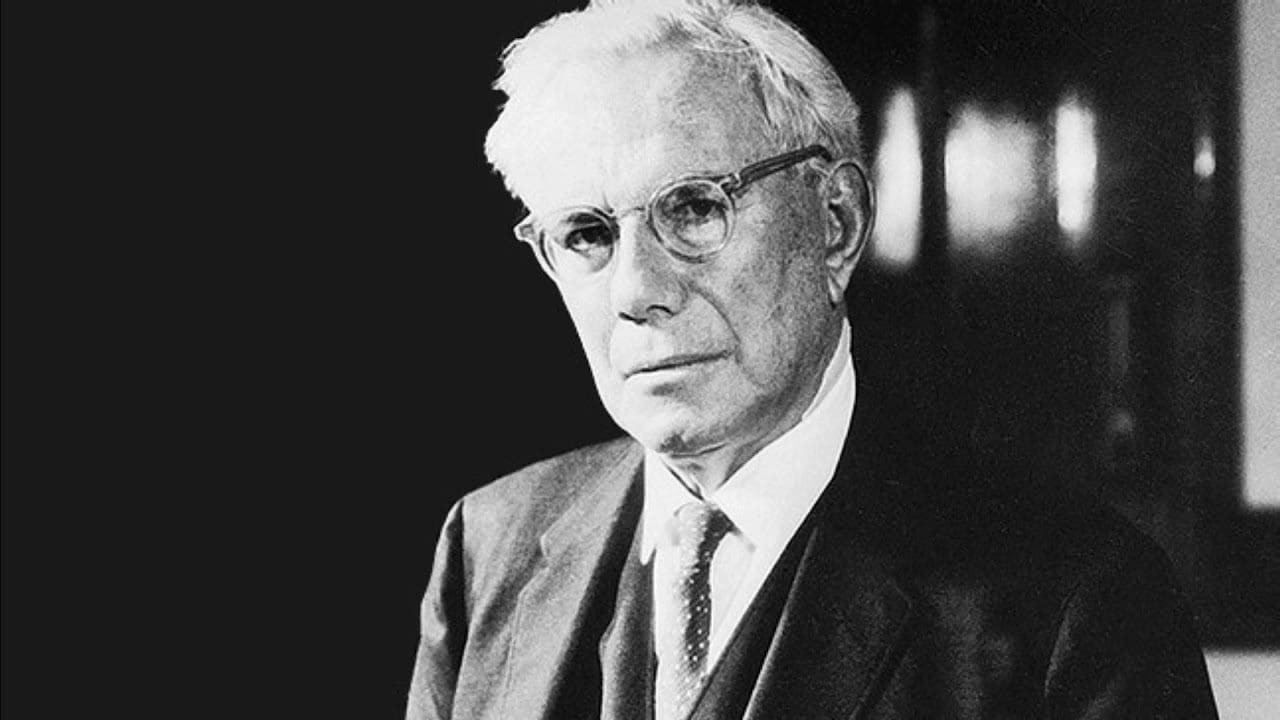

How many misunderstandings and confusions do we face in politics related to notions of power, love and justice? Not much is said if we state that certainly many. We tend to use these terms self-evidently, contrary to the fact that these are very complex phenomena that must be treated carefully both in themselves and in relation to each other. For instance, nowadays, in our individualistic and secularist culture, we are inclined to use an overly narrow understanding of love by treating it as an emotion.[i] In this clarification can help Paul Tillich (1886–1965), a German-born protestant pastor and theologian who, in his short but definitely not easily consumable book entitled Power, Love and Justice,[ii]elaborates on the question. This article does not contain the deep philosophical reasoning of Tillich (for instance, how ontology and metaphysics relate to each other), nor does it examine the relational character of these concepts (there are concise summaries on it[iii]). Rather—parallel to our intention to search for everyday political wisdom— those parts are highlighted which focus on politics or which imply consequences for politics or social ethics.[iv]

‘Love is the drive towards the unity of the separated. Reunion presupposes separation of that which belongs essentially together’

But before suggesting that the notion of power, love and justice and their relation to each other does not have any relevance in public affairs, let us start with the following statement by Tillich: ‘Most of the pitfalls in social ethics, political theory and education are due to a misunderstanding of the ontological character of love. On the other hand, if love is understood in its ontological nature, its relation to justice and power is seen in a light which reveals the basic unity of the three concepts and the conditioned character of its conflicts.’[v] Tillich also argues that theology and philosophy must encounter these notions to establish a constructive theory.[vi] The confusion related to these concepts can stem from both intrinsic and relational misunderstandings. For instance, Tillich’s central problem is that love is usually treated solely as an emotion. It certainly has an emotional element, but the core is different. Those who follow the reductionist perception already disregard another crucial meaning: the Christian ethical one, which relates to the imperative ‘thou shalt’.[vii] Like many of his predecessors, beginning with the Greeks, Tillich differentiates the qualities of love (libido, philia, eros, agape) and—in short—he argues that individuals are, by nature, separate, and love is what unites them. Tillich’s definition focuses on this union when he writes that ‘love is the drive towards the unity of the separated. Reunion presupposes separation of that which belongs essentially together.’[viii]

But what about power, which is a constitutive element in politics? Tillich’s ontological analysis concludes that power is the power of being (and being is the power of being). So he treats power as an indispensable phenomenon of life. What is more relevant to us now is that Tillich is aware of many features and the distinctive character of power and politics. For instance, he writes that ‘politics and power politics are one and the same thing. There are no politics without power, neither in a democracy nor in dictatorship. Politics and power politics point to the same reality. It does not matter which term you are using. Unfortunately, however, the term “power politics” is used for a special type of politics, namely that in which power is separated from justice and love, and is identified with compulsion.’[ix] So, there is no politics without power and politics is not applied morality, but power—understood well—is not alien to justice and love.

But how can we understand the notion of compulsion and force related to power in this equation? ‘Power actualizes itself through force and compulsion. But power is neither the one nor the other. It is being actualizing itself over against the threat of non-being’, writes Tillich.[x] Therefore, compulsion is a necessary character of power (‘Power needs compulsion’), but it is effective only if it remains within the limits of the actual power relation.[xi] Another wise statement is presented by Tillich when he writes that there is no structure (even political structure) without a centre; even egalitarian societies are not exempt from this rule, and the case of an emergency strengthens these centres.[xii]

In Tillich’s understanding, justice is the form in which the power of being actualises itself.[xiii] The theologian summarizes the principles of justice (adequacy, equality) and the forms of justice (distributive, tributive or proportional, and transforming or creative) and later tries to provide a guide to meet justice in personal encounters. At first glance, it might be strange that Tillich argues for the inadequacy of the ‘Golden Rule’ (do to people what one wants to have done by them) in acquiring justice in personal encounters. He writes, ‘for it may well be that one wants to receive benefits which contradict the justice towards oneself and which would contradict equally the justice towards the other one if he received them.’[xiv] Equally interesting —but not unfamiliar in the protestant tradition—is the rejection of applying natural law to all human situations. Among others, the Ten Commandments and the Sermon of the Mount are testaments of natural law valuable in themselves, but ‘for concrete decisions they become indefinite, changing, relative.’[xv]

‘Love in its attempt to see what is in the other person is by no means irrational’

Tillich argues that a unity of justice and love is necessary, and the relation of the former to the latter ‘can adequately be described through three functions of creative justice, namely listening, giving and forgiving’.[xvi] Probably, the most beautiful part of the book is when he unfolds these three aspects. For instance, on listening love, he writes, ‘love in its attempt to see what is in the other person is by no means irrational. It uses all possible means to penetrate into the dark places of his motives and inhibitions. It uses, for example, the tools provided by depth psychology which give unexpected possibilities of discovering the intrinsic claims of a human being.’[xvii]

Unfortunately, Tillich’s separate chapter on the unity of power, justice, and love in group relations, the part that directly investigates the structures of power and social groups, does not provide a substantive added value to our analysis. Yet, some key points should be noted. Firstly, Tillich’s realistic strain is visible when he writes about the impossibility of a world state. He claims that a political world unity presupposes a spiritual unity expressed in symbols and myths, and currently, it does not exist as he wrote in 1952.[xviii] Secondly, he points to the religious character of both the Russian mission in the Cold War, which was based on the idea ‘to save Western civilization through Eastern mystical Christianity’ and ‘“the American dream”, namely to establish the earthly for of kingdom of God by a new beginning.’[xix] Still, the philosophical and theological sections are more profound compared to this part, which is not surprising if we consider the author’s vocation. Yet, as it can be seen, the philosophical investigation of love, justice, and power made by a theologian results in valuable political and social implications.

[i] For an insightful summary on love, see Helm Bennett, Love, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2021 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2021/entries/love/, accessed 22 April 2022.

[ii] Paul Tillich, Power, Love and Justice (London, Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press, 1971)

[iii] For instance, see Dakota Wade, Paul Tillich’s Love, Power, and Justice (1952): A Review & Analysis, Semper Discentes, https://semperdiscentes.life/2021/03/27/love-power-and-justice-a-review-analysis/, accessed 22 April 2022.

[iv] Tillich was in favour of socialist politics, his book entitled Socialist Decision is a prime example of his political ideas. For a summary on this topic, see Matt McManus, ‘The Socialist Politics and Theology of Paul Tillich’, Jacobinmag, https://jacobinmag.com/2022/01/socialist-decision-conservatism-nazis-christianity, accessed 22 April 2022.

[v] Tillich, Power, Love and Justice, 24.

[vi] Tillich, Power, Love and Justice, 1.

[vii] Tillich, Power, Love and Justice, 3-4.

[viii] Tillich, Power, Love and Justice, 25.

[ix] Tillich, Power, Love and Justice, 8.

[x] Tillich, Power, Love and Justice, 47.

[xi] Tillich, Power, Love and Justice, 47-48.

[xii] Tillich, Power, Love and Justice, 8.

[xiii] Tillich, Power, Love and Justice, 56.

[xiv] Tillich, Power, Love and Justice, 79.

[xv] Tillich, Power, Love and Justice, 81.

[xvi] Tillich, Power, Love and Justice, 84.

[xvii] Tillich, Power, Love and Justice, 84-85.

[xviii] Tillich, Power, Love and Justice, 105-106.

[xix] Tillich, Power, Love and Justice, 103.