What approach should Christians take to modern politics? What are their obligations in contemporary public life? Which Christian values should be endorsed in modern democracy and which political instruments are permitted while doing so? Several Christian philosophers, theologians, and politicians have in the past sought to provide answers to these crucial questions. Our series of articles intends to rekindle interest in those authors, firstly because we believe that these authors receive less attention than they deserve, and without forgetting the extensive academic literature on them (since most of them attract serious scholarly interest) we argue that their ideas are underrepresented in public discourse. Secondly, we believe that to answer the questions raised above, one should be able to study acknowledged theologians and philosophers who are well-versed in the wisdom of the Christian faith and base their political arguments on it. Consequently, the political insights of modern theologians will be presented with a special focus on the Christian origins and sources of their ideas. We hope that these articles will increase public interest in these inspiring figures.

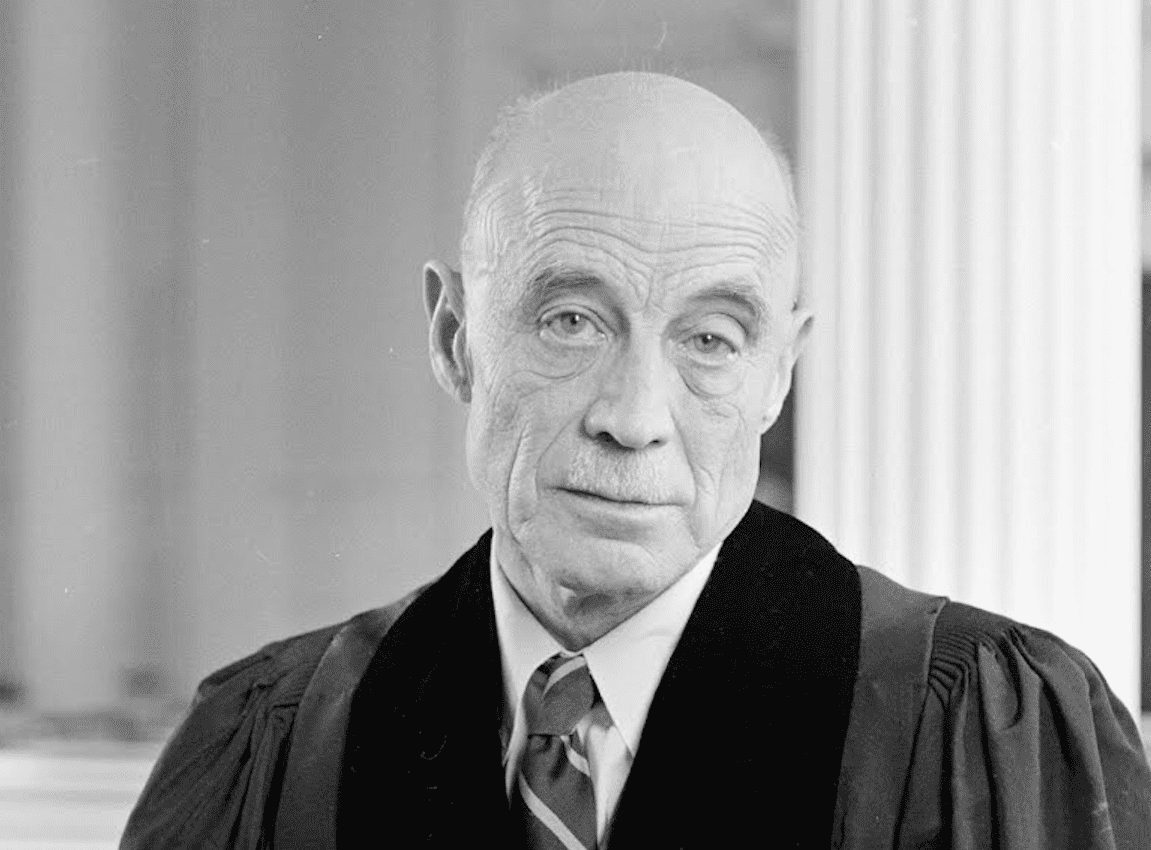

The first article in this series examined the anti-modernism of the Neo-Calvinist theologian Abraham Kuyper, a former prime minister of the Netherlands. The second article focused on Reinhold Niebuhr, one of the most influential twentieth-century American protestant pastors. The third part investigated the political thought of Joseph Ratzinger (1927–), the subsequent Pope Benedict XVI, while the fourth elaborated on Johann Baptist Metz’s “new political theology”. Now, again, the insightful ideas of an essential American protestant theologian from the last century will be recalled. This personality was intimately related to our formerly investigated theologian, Reinhold Niebuhr. In fact, he was his younger brother, professor of theology of Yale Divinity School for decades, Helmut Richard Niebuhr (1894–1962).

Those who have read articles or books by Reinhold Niebuhr know that it is not difficult to make a connection between his theology and his political thought

Just to mention one, his famous Christian realism was heavily grounded in theological arguments (for instance the biblical interpretation of human nature) and yet was used as a perspective to formulate political obligations, or at least, to understand politics properly. In the case of H. Richard, a highly knowledgeable theologian, it is more demanding to point out that connection. Obviously, a lot of researchers recall the debate between the Niebuhr brothers after the Japanese occupation of Manchuria in 1931. The next year, H. Richard’s article published in The Christian Century magazine titled The Grace of Doing Nothing, elaborated on the proper US reaction to Japanese military action. He was advocating repentance, which many understood as inactivity, Reinhold, in his article titled Must We Do Nothing?, while trying to establish an ethically grounded answer, suggested America confront Japan.[i] Naturally, this debate – including the last exchange, H. Richard’s answer to Reinhold titled The Only Way Into the Kingdom of God – would be worth a deeper analysis, but here let us instead gain wisdom from a theological masterpiece, namely H. Richard’s book Christ and Culture[ii]. The book – which begins with the dedication ‘To Reine’ – is treated as one of the most influential theological elaborations of the twentieth century. Now, this book is definitely not about politics per se, since it is about how the relationship between and the problem of Christ and culture is treated from five different perspectives. Yet, politics is part of culture, so the ideas of H. Richard are related to politics in that sense. We believe that book’s arguments are extremely valuable for every Christian who participates in human culture, so should be known and reflected upon by every Christian. We also believe that non-Christians could also benefit from knowing that there are a number of different perspectives with regard to the relation between Christ and culture.

The first school of thought includes those who perceive an opposition, an antagonism between Christ and culture, or as H. Richard explicates, proponents of this wave profess Christ Against Culture. According to this perspective, the Son of God has come into this world, and he is the head and the ruler of it, but has nothing to do with human culture. Moreover, human culture is alien to what Christ represents; it is either Christ or culture. This kind of refusal of the ‘world’ has a specific source in St. John’s Book of Revelation and was widespread in early Christianity, partly since they understood Jesus’s (and the Bible’s) words literally. For instance, one of the crucial authors of early Christianity, Tertullian argued that sin dwells in culture, that corruption and civilization go hand in hand, and that Christians should not participate in culture, so military services, trading, arts, and philosophy are to be rejected. Before suggesting that this perspective has no relevance in the modern era, let us remember Leo Tolstoy’s peaceful and anarchic Christianity. Although the Russian writer accepted craftsmanship and certain kinds of arts (those that can circulate the right Christian ideas), he called the Church an anti-Christ institution and encouraged others to refuse the exercise of civic duties.

As H. Richard suggests, this extremity is attractive, since there is a kind of genuineness in it (those advocating it do what they profess); moreover, it is a necessary way of thinking in Christianity, because it can foster spiritual renewal. Yet, it is not satisfactory. Of H. Richard’s logical and theological criticisms formulated against them, only two will be mentioned here: first, one cannot escape the entirety of human culture as it is suggested by some Christian authors; we are born into human culture, so much so that neither the aforementioned Christian authors nor Jesus could escape it. Second, by differentiating between virtuous “anti-cultural” and evil “cultural” individuals and groups, one can easily fall into the sin of pride.

At the other end of the scale are those who believe in the Christ of Culture. Jesus – for the representatives of this group – is the Messiah of society, the one who fulfils the hopes and aspirations of individuals. He is also often treated as an (or the greatest) educator, philosopher, or reformer. According to this perspective, there is no tension between Christ and what he said, and culture, in fact, he is understood through culture. One of the essential characteristics of this attitude, which is one of its greatest fallacies, is that it sees Christ through its own culture; it only focuses on those attributes of Christ which fit the current culture and leaves out those which are not reconcilable. H. Richard reminds us that this perspective was very common in his era, especially in Protestant circles. Of the many labels given to it (e.g. liberal theology, liberal Christianity) he prefers to use the term Cultural Protestantism.

Although the roots of this train of thought go far back to the Gnostics and Abelard in the Middle Ages, on the threshold of modern times several great philosophers (Locke, Leibniz, Kant, Jefferson) professed its core idea, namely that through moral education peaceful and cooperative societies could be attained. The greatest representative of this thread is the Protestant theologian Albrecht Ritschl, who did not find any antagonism between the Church and the greater community. He even condemned monasticism and pietism for separating the Church from the ‘world’. H. Richard highlights that one has to acknowledge the richness of Ritschl’s theology, and underscores that he– unlike others – did not wish to connect the contemporary intellectual streams, for instance, nationalism, capitalism, or materialist ideas with Jesus Christ. What he did was rather “picking and choosing” (naturally, this is not a term H. Richard used): of all the characteristics of Jesus Christ, he highlighted the value of love at the expense of power and justice.

Numerous thinkers and movements, especially in Protestantism, advertised this central notion of the need to fully participate in culture and uphold its institutions, without suggesting any tension between Christ and culture. A morally more powerful but theologically less profound movement was The Social Gospel led by Walter Rauschenbusch. Although not in Christ and Culture, but in The Kingdom of God in America[iii], H. Richard formulates a devastating argument on how the liberal wave of Christianity empties the essence of Christianity. In fact, this liberal wave plays into the hands of those non-Christians who wish to tame Christianity or Christ, by equating Jesus with love. As H. Richard put it: ‘A God without wrath brought men without sin into a kingdom without judgment through the ministrations of a Christ without a cross.’ [iv]

The remaining three perspectives are all middle-of-the-road ones between the two radical paths. They do not oppose culture, but they do not shape Christ only through their own culture. In other words, they believe that while there is a conflict between Christ and culture it is not an antagonistic one. For them, the main question is not the problem of Christ and culture, but the relation between God and human beings. They all agree that obedience should be attributed to God (more specifically, to God in Christ and to Christ in God) and that it must be expressed in everyday cultural life. Yet the representatives of these three groups (in short, synthesists, dualists, and conversionists) think differently on a number of issues, and while it is possible to point to denominational differences to explain those diverging thoughts, the central cleavages do not stem from them.

The first group believes in a synthesis between Christ and culture, suggesting that the ultimate outcome is Christ above Culture

The first group believes in a synthesis between Christ and culture, suggesting that the ultimate outcome is Christ above Culture. Their understanding is more complex than that of the radicals, as they are aware of the gap between Christ and culture, yet they approve of both. They accentuate that Jesus is God but also a human being at the same time, and similarly, in culture, there is a mixture of the divine and the profane, of holy and evil. For them, the extraordinary ideas of Christ (e.g., you should leave your family to follow Jesus, let someone slap your other cheek) are too radical to be taken literally in a human civilization, and yet they are too concrete to be discarded entirely. Up to this point, there is no great difference between the synthesists and the other two streams, however, as H. Richard points out, several biblical phrases illustrate this kind of balancing between Christ and culture, while maintaining the former’s overwhelming supremacy. So this train of thought is closer to the Christ of Culture. It highlights the importance of culture, yet it does not humanize Christ, but places it above the culture, rather than into it. Clemens of Alexandria, the Christian ethicist, pointed out the importance of education and being a morally decent individual who follows cultural norms, without suggesting that these would lead to redemption.

The greatest representative of this thinking is Thomas Aquinas, who was a master of connecting different realms (e.g., philosophy with theology, God’s law with natural law, Christ and culture) without blurring the line between them, and without questioning Christ’s superiority over culture. Aquinas’s life itself perfectly illustrates his beliefs: on the one hand, he was a monk who took his three vows seriously and “rejected the world”, while he was part of the medieval Church, the main cultural actor at the time. By differentiating separate kinds of laws, of happiness and of paths leading towards the latter, he demonstrated that neither Christ nor culture had to be denied to achieve specific, good human goals. Beyond his several merits (for instance his contributions to medieval culture), Aquinas taught us that it is possible to build systems from elements that are seemingly conflictual. He also highlighted that from a certain level upwards, humans and human rationality are bound by limitations.

H. Richard formulated three concerns with regard to this perspective. First, he noted that one can never suggest with certainty that a theoretical system would perfectly fit every historical time and situation. Aquinas’s theories echo the characteristics of European medieval times, which – even if plausible in his historical context – might be useless in other places or in other times. Second, if we are certain that we are able to acquire a perfect knowledge of the world, and we suggest that we are not bound by intellectual limitations, we violate the superiority of God. Third, although this perspective acknowledges the sinfulness of human nature, its critics repeatedly emphasize that it does not take sin seriously. This is the notion in which the next variant certainly performs better.

The central question for those who find the relation of Christ and Culture In Paradox, is the divide that lies between God and us humans. They focus heavily on two notions: God’s grace, which is solely connected to him, and unmerited; and man’s sinfulness, which is not just simply a lack of morality or good deeds, but the evilness that lies deep within man’s heart. Human beings dwell in sin, and although one must distinguish between virtuous and evil acts, the difference is almost irrelevant compared to the chasm that spans between man and God. Godlessness, which is the essence of sin, has also corrupted every human enterprise, including culture. Culture as a whole is cracked: not just those who seem evil, but also those who seem virtuous. Dualists often call attention to the fact that in several cases, virtues are used to cover up sins. What is also common among dualist authors is that they use paradoxes, most importantly stressing the dynamic relation between law (or sin) and grace, or God’s wrath and his mercy.

However, dualism is more a motif than a school of thought, writes H. Richard. It is harder to detect these ideas, but most of those who use them are the followers of (St.) Paul, such as Marcion, Augustine[v] or Luther. Paul himself also expressed the idea of Christ having destroyed the wisdom of the wise, and pointed to the unrighteousness of us all. Yet as a result of redemption in Christ, Jesus’s light can transform our hearts and allow the appearance of benign achievements in human civilization and culture. One of the main characteristics of dualist thought – which also differentiates it from synthesist ideas – is it proposes that several cultural instruments are utilized negatively. According to dualists, the essence of several human enterprises (for instance the state and political power) is not to unfold human virtues, but to control human sins. This thought was quite obviously endorsed by Martin Luther, who favoured the strong hand in politics. He used antinomies and paradoxes to express his ideas, distinguishing the kingdom of God (which is the kingdom of mercy and grace) from the kingdom of the world (which is the kingdom of wrath and severity). Although he believed that the latter is deeply depraved, and human beings, by themselves, are unable to get free from self-love, Luther approved of human culture, including theology, music (which is God’s gracious gift), fair trade, and several professions. Human beings are by their nature active and dynamic, compelled to constantly engage in activities, and ‘[f]rom Christ we receive knowledge and the freedom to do faithfully and lovingly what culture teaches or requires us to do.’[vi] Life is both profoundly tragic and joyful, Luther suggested, and there is no earthly solution to this dilemma.

Dualists were talented in investigating the seriousness of sin and the deepness of human corruption, both on an individual and on a collective level, while at the same time pointing out the power of Christ’s work and the dynamic character of the relationship between God and man, grace and sin. There is an appealing sincerity in Paul’s and Luther’s “reports” on how they fought their spiritual battles. Yet, their weak or self-willed followers can fall easy prey to the temptation to ignore the Commandments, misled by the apparent relativity suggested by dualist thought. In addition, cultural conservatism benefited from this kind of thought: first, it is easy to argue for the preservation of traditional systems, arguing that they are essential in controlling sin (without realizing that the system is also a source of sin); second, some dualists who, similarly to Paul and Luther, focus only on religion, tend to forget that other spheres (economy, politics, etc.) might also require reforms.

The last variant, which represents the central tradition of the Church, considers Christ the Transformer of Culture. Like dualists, they recognize the significance of sin, but they are more positive, or optimistic, grounded on three main assumptions. First, for them, Creation is a central topic, and they focus on God’s declaration that Creation was good. Second, they separate Creation from the Fall, so human beings are not of an evil heart, only corrupted, misdirected. They have fallen out of good, so the existence of good is supposed. The third assumption is related to a kind of view on history; for conversionists, history is “played” between God and human beings, as history is God’s magnificent acts and the human answers to it, therefore anything is possible in history.

One of the sources that inspired this school is John’s Gospel. In the author’s mind, everything is good, and there is no rigid distinction between the goodness of spiritual and the evilness of physical/material. What is more, John gave spiritual meaning to the latter in several cases, approving of human goods (for instance, in the case of the wine and the bread, which are the blood and body of Christ). In the Fourth Gospel, the created world is a corruption of the good; sin is the denial of the principle of life, so it is a negative concept. Sin would not exist if there was no life. For John, the Creation and the Fall are not historical events, rather the consequences of turning away from God, a condition that affects every human being. It is into this corrupted environment that Jesus comes, as a transformer of human actions, and of the whole human culture. However, it should be mentioned that in John’s Gospel only a few are chosen in the end. This is why John’s Gospel is regarded as the most universal and the most exclusive at the same time.

Social renewal was one of the great themes of the fourth and fifth centuries

The great scholar of this era is, of course, Augustine. Although his extensive thought could be connected to almost all the variants, the conversionist thread is very significant in it. In his view, Christ is the transformer of culture, who redirects and regenerates all human life. Also, in Augustine’s thought, the goodness of Creation was a recurrent and intense motif. Although humans were to worship and dignify the God who created them good, they became corrupted, and sin was essentially the turning away from God (the good), human disobedience. Individual sins have social consequences: culture itself also became corrupted, full of self-concern. Yet, the existence of evil in the cultural sphere cannot exist without the precondition of a “positive” essence. To give an example: war can only be understood in relation to peace. Augustine also highlights that Christ comes into this world to herd the misdirected, and it is a Christian’s freedom and responsibility to take part in human affairs.

The last great conversionist analyzed extensively by H. Richard is Frederick Maurice, the nineteeth-century English theologian. Maurice believed that Christ rules the world and human beings – who are social animals – are not just bound together as a community by their fellow human beings, but also by God, Jesus Christ and the Holy Spirit. The sin of man was that he wanted to reach something he can only receive: man wanted to be his own God. This sin of pride is present even in the Church and the sects, Maurice claimed. Yet, it is a mistake to focus on sinfulness, he suggested, as sin-centeredness misdirects us. Rather, Maurice opined, one has to focus on Christ to reach a Christ-centred world, which is a historical opportunity.

What H. Richard underlines in his last—unfamiliarly titled—chapter, titled Concluding Unscientific Postscript, is not the idea that all Christians should be familiar with these abstract categories in great philosophical depth, and debate about theological variants, searching for or claiming to have found the best one. Instead, Christians should make decisions and act, and also they could observe their line of actions and arguments behind them, based on the knowledge of these different perspectives. We believe that following H. Richard’s advice, living as we are in the midst of ever newer Instagram and TikTok challenges, would be an inspirational change for us all.

[i] For an insightful summary see John D. Barbour: Niebuhr Versus Niebuhr: The Tragic Nature of History (Christian Century, 1984 Nov 21. pp. 1096-1099) Available at Religion Online, https://www.religion-online.org/article/niebuhr-versus-niebuhr-the-tragic-nature-of-history/

[ii] H. Richard Niebuhr: Christ and Culture (New York: Harper & Row, 1951)

[iii] H. Richard Niebuhr: The Kingdom of God in America (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1937)

[iv] ibid. 193.

[v] Regarding Augustine, H. Richard acknowledges the presence of dualist elements but argues that he is more connected to the last group, the conversionists.

[vi] H. Richard Niebuhr: Christ and Culture (New York: Harper & Row, 1951) 175.