French Jesuit priest and scholar Pierre Teilhard de Chardin’s biography and lifepath is not the one you would normally expect from an ordained priest of the Catholic Church. Throughout his life and work, his main interests were theology and palaeontology, two disciplines that initially found themselves at odds due to the religious scepticism surrounding the concept of evolutionary theory. On the other hand, Catholic, and within that, Jesuit thought in particular has a long tradition of diligently tending to matters in both the spiritual and scientific domains, without losing the harmony in their beliefs. The episodes of Pierre Teilhard de Chardin’s life and work demonstrate that science and religion not only do not contradict each other but can harmoniously combine to create something of great significance.

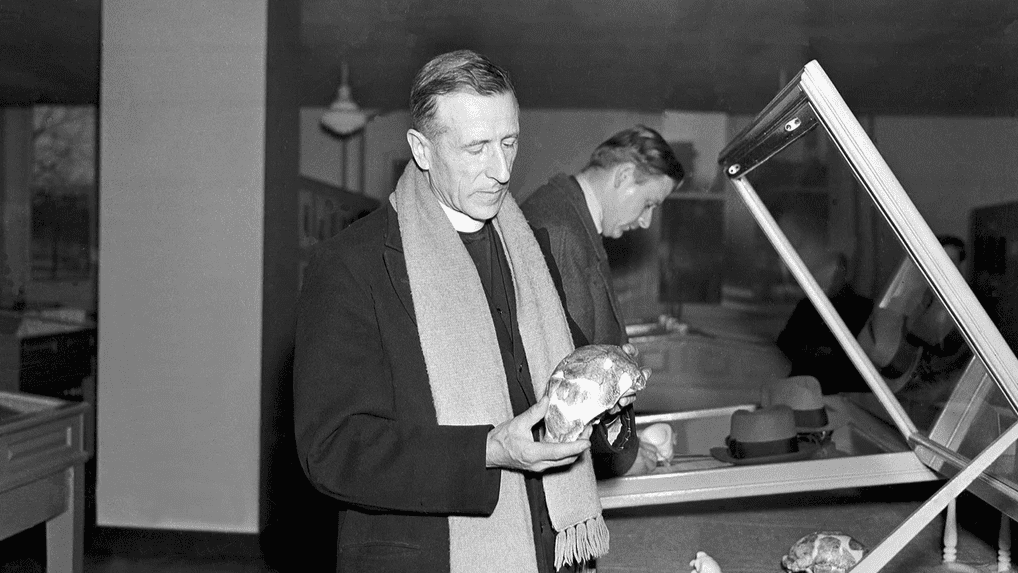

When it comes to Chardin, from the very beginning of his life journey, the synthesis of faith and science permeated his worldview. Born in 1881 in France, his father was a keen naturalist, whereas his mother was the one who awakened him spiritually. He completed a Jesuit college, and then graduated from the top universities of France, including the University of Paris. Besides, he also served in the First World War and earned the Legion of Honour, the highest French order of merit. Upon the completion of his studies, he participated in geological expeditions to Asia,

making a significant contribution to the study of Peking man,

an extinct subspecies of Homo erectus. It was during these voyages that he started to distil his experiences into papers, elaborating on his ideas about religion, science, the universe and the place and role of humans in it.

His life is captivating and filled with unexpected twists, and so are his thought-provoking ideas. He began writing his essays, such as ‘The Divine Milieu’, ‘Man’s Place in Nature’, ‘Hymn of the Universe’, and others. However, his most celebrated creation is the work titled ‘The Phenomenon of Man’, a synthesis of his worldview and a grand endeavour to merge the realms of science and spirituality, which, it should be noted, sparked considerable controversy.

In this seminal essay he begins his inquiry with stating the essence of his approach. To him,

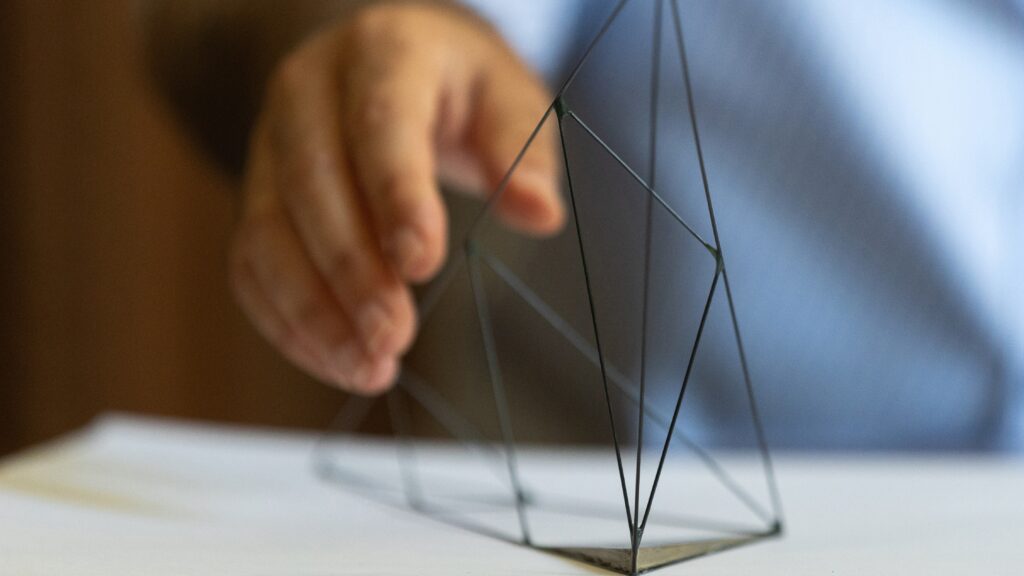

the universe is not divided, but forms a unified, organic whole

—so does religion, science, and philosophy, inseparably tied to each other. In his opinion, it is pivotal to view the world holistically:

‘During the last fifty years or so, the investigations of science have proved beyond all doubt that there is no fact which exists in pure isolation, but that every experience, however objective it may seem, inevitably becomes enveloped in a complex of assumptions as soon as the scientist attempts to express it in a formula. But while this aura of subjective interpretation may remain imperceptible where the field of observation is limited, it is bound to become practically dominant as soon as the field of vision extends to the whole. Like the meridians as they approach the poles, science, philosophy and religion are bound to converge as they draw nearer to the whole.’

In his work, Chardin adopts a Darwinian perspective, with evolution playing a crucial role in delivering his central argument. While encapsulating the essence of his ideas in a brief description is inherently hard, it is possible to distil his argument down to as follows: all inanimate matter of the universe is bound to progress to greater levels of complexity, emerging from the primordial chaos. Evolution, which he was the proponent of, is important in that regard, as it is the process of the biological development, which, at a given point during the evolutionary process, acquired a certain level of complexity, and therefore, intelligence—to be found, of course, by humans as the only sentient species. However, evolution goes beyond its biological boundaries, and

as a result of the development of thinking organisms, the the noosphere emerges

—a thinking layer of the Earth, exemplified by ideas we share, knowledge we develop and mental constructs we create. Eventually, this process of gradual emergence of complexity, which, thanks to human intelligence, will also be assisted by science, will culminate in the so-called ‘Omega Point’, the ultimate state of unity of the entire universe. Thus, at the end of the universe and at the final stage of history, everything that exists will merge into one greater consciousness:

‘Seen from this point of view, the universe, without losing any of its immensity and thus without suffering any anthropomorphism, begins to take shape: since to think it, undergo it and make it act, it is beyond our souls that we must look, not the other way around. In the perspective of a noogenesis, time and space become truly humanized—or rather super-humanized. Far from being mutually exclusive, the Universal and Personal…grow in the same direction and culminate simultaneously in each other…The Future Universal could not be anything else but the Hyper-Personal at the Omega Point.’

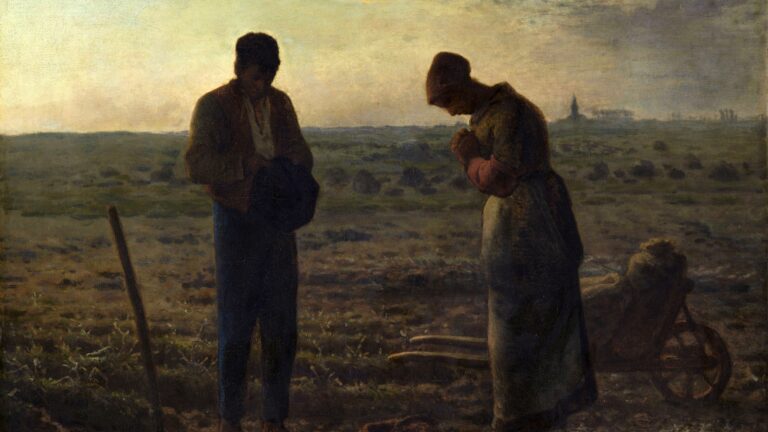

It is not hard to recognize in these lines a reference to the Bible, where God in the Book of Revelation describes himself as ‘the Alpha and the Omega, the beginning and the end’.

At first, the work received bad feedback from both the Church and the scientific community. Although the Holy Office did not put it on the Index Librorum Prohibitorum (list of forbidden books), the book received an official ‘warning’, as in the opinion of the Catholic Church, it could have had a disruptive effect on the minds of the believers, especially the youth. Academia in turn criticized Teilhard de Chardin for introducing ambiguous and non-verifiable terminology, such as ‘love energy’, or notions that humans will ultimately escape the heat death of the universe at the end of time via their spiritual power, as the latter is not subject to entropy. He could not respond to the critical reviews, as the book was published posthumously in 1955.

However, more recently, both camps have turned their attention to the intellectual legacy of Pierre Teilhard de Chardin. A multitude of scholars from different disciplines have discovered important ideas affecting their fields in his oeuvre. The ‘Phenomenon of Man’ roused the interests of many, including but not limited to astrophysicists, cosmologists and astrobiologists (scientists preoccupied with the search of extra-terrestrial life and intelligence), as they hypothesize

other intelligent species might also take part in the great universal uplift towards the Omega Point.

The ecclesiastical perception has also undergone a significant change. Albeit the warning has not been withdrawn, in practice, the work of Teilhard de Chardin is highly regarded, as none other than two Popes have praised it. In one of his speeches, Pope Benedict XVI drew a parallel between the teachings of Saint Paul, who wrote that one day the ‘world will become a form of living worship’, and the concept of the Omega Point. The pontiff wrote: ‘It’s the great vision that later Teilhard de Chardin also had: At the end we will have a true cosmic liturgy, where the cosmos becomes a living host. Let’s pray to the Lord that he helps us be priests in this sense, to help in the transformation of the world in adoration of God, beginning with ourselves’.

The life and works of Father Pierre Teilhard de Chardin serve as an example that for a devout believer, faith and science need not be in conflict. Even if one does not fully agree with his teachings, they nonetheless inspire us to find paths that allow us to organically merge the two realms, without causing a rift in our worldview.