Pope Leo XIV, on the occasion of the Jubilee of Governments on 21 June, met with members of the International Inter-Parliamentary Union from 68 nations in which he invited the participants to take into consideration the natural law—God’s unwritten law inscribed in the hearts of men—as the criteria for legislation.

‘In order to have a shared point of reference in political activity, and not exclude a priori any consideration of the transcendent in decision-making processes,’ Pope Leo explained, ‘it would be helpful to seek an element that unites everyone. To this end, an essential reference point is the natural law, written not by human hands, but acknowledged as valid in all times and places, and finding its most plausible and convincing argument in nature itself.’

Modern critics—especially those on the political left—contend that law should be enacted and enforced exclusively by human authorities, free from any moral deliberation. Legal positivists not only argue this position but also identify natural law with the tenets of the medieval Catholic Church, which are no longer relevant in an evolved secular society whose sole purpose is the maintenance of social cohesion.

‘Cicero…defined natural law as “right reason, in accordance with nature, universal, constant and eternal”’

It cannot be denied that the concept of natural law was systematized by the Roman Catholic Church during the Medieval era, which in turn contributed to the development of Western civilization. Yet its universal recognition as the foundation of all law dates back to Antiquity. This is why the Pontiff cited Cicero (106–43 BC), who defined natural law as ‘right reason, in accordance with nature, universal, constant and eternal, which with its orders invites to duty, with its prohibitions dissuades from evil.’

Indeed, building upon the laws of Zeus and of the gods, as written by Sophocles in his epic tragedy Antigone (442 or 440 BC), Cicero formalized the natural law as an innate aspect of the human person, whereby he could decipher between good and evil:

‘Therefore, the most learned men decided to proceed from the law [a lege]…law [lex] is the highest reason, inherent in nature, which enjoins what ought to be done and forbids the opposite. When that reason is fully formed and completed in the human mind, it, too, is lex.’

For clarification, unlike in English, Classical Latin has two words for law—‘ius’ and ‘lex’. While interchangeable, Roman jurists utilized ‘ius’, which signifies law in general, or a system of laws; ‘lex’ referred to a particular species of positive law.

The natural law Leo XIV spoke of was the lex naturale, which is distinct from the ius naturale. The latter was highlighted during the modern era by the Dutch scholar and jurist Hugo Grotius (1583–1645) as a point of reference for Christian monarchs to cease waging war against each other. For Grotius, as he stipulated in his De iure belli ac pacis, natural law (ius naturale) was a dictate of right reason that determines whether an act, conforming or not to man’s rational and social nature, possesses moral baseness or moral necessity. Such an act is either forbidden or commanded by the author of nature, God.

Grotius, nevertheless, paved the way for legal positivism by inadvertently stripping the Creator from natural law, stating that it would exist ‘etiamsi daremus Deum non esse’ (even if we were to say that there is no God). Thereafter, natural law was radically reinterpreted as a means of individual self-preservation and utilitarianism, as seen in Darwinism—i.e., survival of the fittest—or, worse, the notion of a superior Aryan race conceived by the National Socialists.

‘Natural law, which is universally valid apart from and above other more debatable beliefs,’ the Pope added, ‘constitutes the compass by which to take our bearings in legislating and acting, particularly on the delicate and pressing ethical issues that, today more than in the past, regard personal life and privacy.’

‘Natural law…constitutes the compass by which to take our bearings in legislating and acting’

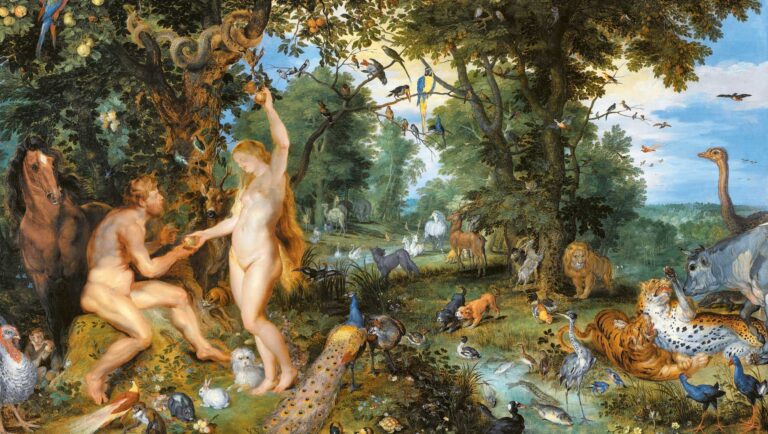

In this, the Pope reminded us that we are not mere individual statistics, but rather created in the image and likeness of God (Genesis 1:26–27), and thus participate in His divine wisdom and goodness. It is He who gives us mastery over the ability to govern ourselves with a view to the true and the good—that is, to act in accordance with our conscience.

A primary example of this is St. Thomas More (1478–1535), whom the Pontiff presented to the audience as a model to be imitated. More, the patron saint of statesmen and politicians, was Chancellor of England during the reign of King Henry VIII (r. 1509–1547). He refused to take an oath that required all subjects of the Crown to recognize Henry—not the pope—as head of the Church of England, as well as to accept Henry’s invalid marriage to Anne Boleyn, his second of six wives. St. Thomas was thereafter imprisoned in the Tower of London for 15 months and subsequently beheaded. In this, the Pope says, More demonstrated a ‘readiness to sacrifice his life rather than betray the truth [that] makes him a martyr for freedom and for the primacy of conscience.’

‘If we consider the service that political life renders to society and to the common good,’ the Holy Father said, ‘it can truly be seen as an act of Christian love, which is never simply a theory, but always a concrete sign and witness of God’s constant concern for the good of our human family.’

‘Sound politics,’ Leo continued, ‘can offer an effective service to harmony and peace both domestically and internationally,’ especially in light of the senseless wars that are still going on, as well as ‘the unacceptable disproportion between the immense wealth concentrated in the hands of a few and the world’s poor.’

Hence, Leo XIV hinted last month that Christians and non-Christians alike—even the United Nations, via its Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948—can only benefit from natural law. This is because, as quoted above, it ‘is universally valid apart from and above other more debatable beliefs, [and] constitutes the compass by which to take our bearings in legislating and acting, particularly on the delicate and pressing ethical issues that, today more than in the past, regard personal life and privacy.’

Related articles: