In conservative theory, two famous fences have long illustrated how we approach reform. Chesterton coined both, yet over time, a third has become necessary.

Debates over reform reveal ideological differences. Contrary to stereotype, conservatives do not simply oppose change, but question whether change is inherently good. As Patrick Deneen observes in his book Regime Change (2023), we do not elevate change above all else; unlike progressives, we doubt that all change equals progress.

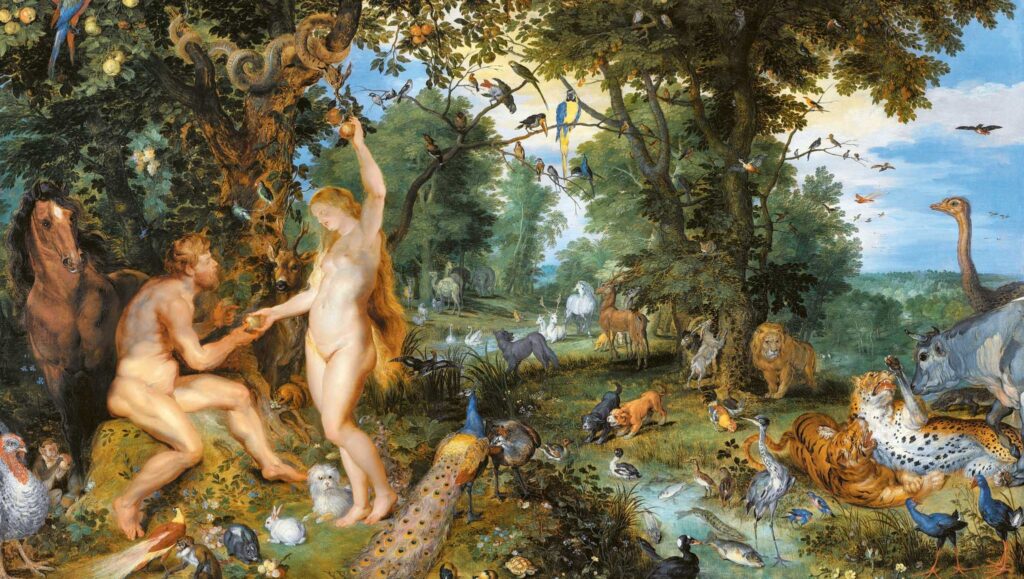

The image of a fence often illustrates this posture. Where progressives may tear it down without reflection, the conservative instinct demands pause. Roger Scruton put it succinctly: conservatism starts from the sentiment that good things are easily destroyed, but not easily created. Edmund Burke expressed the same scepticism in his critique of the French Revolution (1790), rejecting projects that sought to remake man and institutions without historical grounding.

The fence has thus become a central pedagogical image of conservative thought. While liberals and socialists feel no obligation to stop, conservatives do. Traditionally, two attitudes are invoked—the Burkean and the Chestertonian. To these I now add a third.

Burke’s Fence

In The Thing: What is Christianity? (1929), Chesterton described what this article call ‘the Burkean fence’. His insight was simple: most people lack the humility to grasp why institutions exist. We inherit generations of wisdom in customs and institutions, and as Burke observed, traditions contain latent knowledge beyond the reach of individual reason.

Progressive reformers often attack inherited institutions without understanding their purpose. They see a custom, find no use, and abolish it. Burke and Chesterton rejected this: if you see a fence but do not know its function, you have no right to remove it.

‘Contrary to stereotype, conservatives do not simply oppose change, but question whether change is inherently good’

The fence symbolizes laws and norms built to solve now-invisible problems. Tearing them down without comprehension risks reviving the issues they once addressed. This is not opposition to change, but to reckless change.

The monarchy illustrates the point. For longer than democracies have existed, monarchies have organized societies. Yet they are met with criticism and incomprehension. Even when largely ceremonial, they are not meaningless: they embody responsibility, symbolize unity, and provide continuity beyond electoral cycles. Governments fall, parliaments shift, prime ministers are replaced—but the monarch endures.

The Burkean perspective insists: before dismissing monarchy as empty pomp, one must understand what it preserves.

Chesterton’s Fence

Alongside Burke’s fence stands Chesterton’s second perspective, likened to a white post but equally a fence. It builds on Burke’s insight that understanding precedes reform, yet recognizes that this alone is insufficient.

Traditions can become flawed, and institutions may decay. Chesterton argued that preservation requires vigilance and renewal. In Orthodoxy (1908), he wrote: ‘Leave a white post alone, and it will soon turn black; if you want it white, you must repaint it—you must have a revolution. In short: to keep the old white post, you must have a new white post.’

Institutions need not have strayed from their original purpose; often, the world around them has changed. Climate shifts, technologies arise, populations move, and economies transform. What sufficed in 1850 may be inadequate in 1950 and unsuitable in 2050. The function remains, but the form requires attention.

The Catholic Church practised this: when pagan lands were Christianized, festivals were redirected rather than abolished. Sweden’s Lucia celebration, once pagan, was reshaped to honour Saint Lucia. The form—light in darkness—remained, but meaning changed. The Church showed traditions can be redirected, not destroyed.

‘The Church showed traditions can be redirected, not destroyed’

In our time, where some institutions are corrupted while others remain sound, this distinction is crucial. Some traditions must stand even as they weather. Change may degrade, but renewal enriches. Yet here a third situation arises—one Chesterton never answered.

The Stewards fences

Burke and Chesterton assumed that an unknown fence is worth preserving or reforming—sometimes reforming to preserve. Both presuppose that the underlying purpose is sound. But history and contemporary politics abound with institutions so corrupted or hostile to conservative ends that renovation is futile—or dangerous. In such cases, the most conservative act is demolition.

Like a fence rotted from within, ready to collapse from damp and decay, institutions, too, can disintegrate. Then it is wiser to replace them entirely than to salvage fragments. Burke’s insight can be inverted: if the fence is abandoned, there is likely a reason. A fence that no longer serves its purpose is no fence at all.

NASA illustrates this: once a proud institution, but after losing its spark. To Elon Musk, it was easier to succeed with founding SpaceX instead of working at NASA. Similarly, some cultural movements are so alien to conservative aims that reform is counterproductive. For example, it can never be a conservative pride organisation.

Curtis Yarvin has noted the paradox: sometimes sweeping change is easier than small adjustments, since every minor reform meets as much resistance as a major one. Moreover, reform risks legitimizing the corrupted framework, binding one to its terms. In such cases, building anew is more conserving.

The Steward’s stance is clear: if a fence no longer serves any function, or obstructs higher ends, it is not conservative to let it stand or to reform it. A rotted fence in the forest that hinders no one is merely an ugly remnant. So too with institutions erected for false purposes.

The Principle

Conservatives can at times embrace radical change—but only when it restores order and continuity. Burke teaches us first to understand: if an institution bears wisdom, preserve it. Chesterton reminds us that preservation requires renewal. And if the institution is corrupted at its core, Steward’s Fence commands: tear it down and build anew.

The principle is simple: institutions exist to serve purposes. When the purpose disappears, so does legitimacy.

This is not radicalism but realism: the world changes, and some institutions deserve saving while others must fall. True conservative virtue is the wisdom to discern which fences must be kept, repainted, or removed.

Related articles