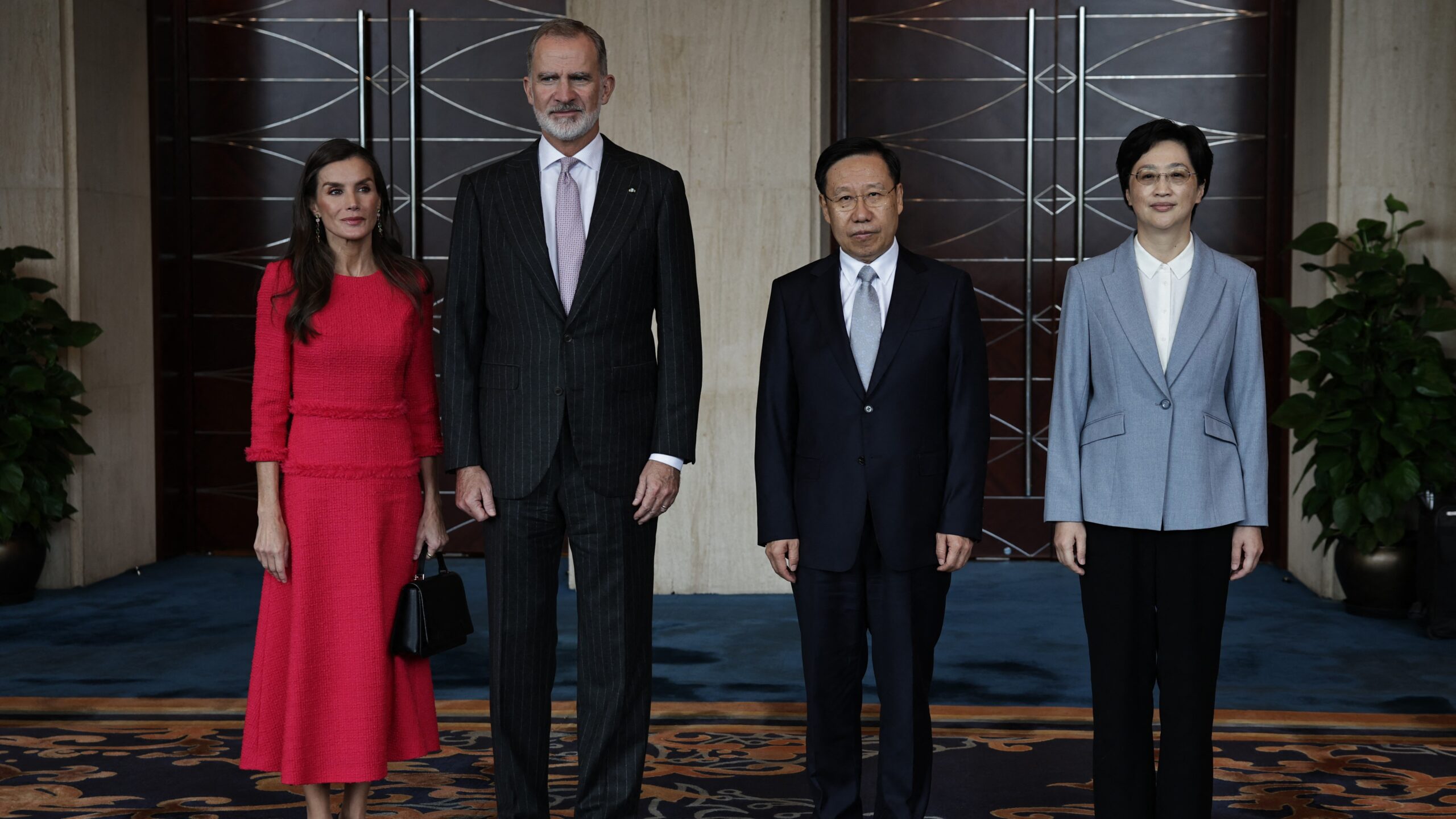

When King Felipe VI and Queen Letizia arrived in Chengdú this November, it marked Spain’s first state visit to China in nearly two decades.

The occasion was presented as a triumph of diplomacy—an opportunity to deepen economic cooperation and promote Spanish culture.

Yet beneath the ceremony lies something more complex: the visible outline of Madrid’s new foreign-policy doctrine, and the uncomfortable ambiguity of its place in the post-American world.

A Royal Visit in the Age of Realignment

The visit’s programme revealed both ambition and anxiety. The King presided over a large business forum with more than four hundred executives from both countries, aiming to narrow a €40 billion trade deficit and attract Chinese investment.

Meanwhile, the Queen attended a homage to Antonio Machado—a poet of exile whose verses now circulate in Chinese translation—and met with Chinese Hispanists in Beijing.

The dual emphasis on economic pragmatism and cultural prestige was meant to project confidence: Spain as a global civilization seeking renewed relevance in a competitive world.

Yet the symbolism cannot hide the fact that this outreach forms part of Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez’s broader effort to find breathing space between Washington and Beijing.

Sánchez’s Gamble: Pragmatism or Refuge?

Sánchez has spent the past three years cultivating closer ties with China. During his 2024 visit to Beijing, he declared that ‘a trade war would benefit no one’—signalling a softer line than that of Washington or even Brussels.

His government’s China policy is built on the promise of diversification: a desire to open new markets and attract investment at a time when Donald Trump’s second presidency has reintroduced tariffs, reshoring policies, and renewed demands for European alignment.

For Madrid, China represents not only opportunity but refuge—a way of stepping out of Washington’s shadow without openly breaking with it.

Yet refuge is not strategy. The risk is that Spain, in fleeing the constraints of the transatlantic relationship, is running into the arms of a partner whose embrace is far tighter. Beijing’s economic magnetism conceals a growing capacity for political leverage. What begins as trade can end as dependence; what starts as outreach can become captivity.

Hungary’s Lesson: Connectivity with a Compass

Contrast this with Hungary’s approach. The Hungarian concept of connectivity, articulated by Balázs Orbán, rests on genuine equilibrium: Budapest cooperates with every major power—the United States, the European Union, China, and even the Turkic and Arab worlds—without being in conflict with any. It is not neutrality but sovereign realism, a form of diplomacy that turns geography into advantage rather than subordination.

In Hungary’s version of connectivity, engagement serves the national interest; it does not replace it. Hungary’s relations with Beijing do not preclude its NATO commitments; its ties with Washington do not exclude its openness to the East.

By keeping all doors open and none dependent, Budapest achieves the rarest form of strategic success in today’s world: to be courted by all, hostage to none.

Spain’s new China policy, by contrast, lacks that balance. It is not driven by confidence but by displacement. Unable to find a secure footing with Washington and uneasy within a fragmented European Union, Madrid looks to Beijing less as a partner of diversification than as a shelter from rejection.

This is not connectivity but escapism—a movement away from one pole without understanding the pull of the other.

Civilizational Orientation Still Matters

For Spain, the irony is profound. A nation that once defined the Western world is now searching for its place in the global East.

Yet Spain’s vocation has never been Eurasian. Its civilizational reach has always been Atlantic—stretching across the ocean to the Americas, where its language, faith, and culture remain living realities.

To pursue commerce with China is legitimate; to mistake it for destiny is not. Spain’s cultural diplomacy in Chengdú and Beijing may win headlines, but its deeper strength lies in its ties to the Ibero-American world—nations that share its moral imagination and historical continuity. In abandoning that natural sphere, Spain risks not only economic miscalculation but civilizational amnesia.

Between Sovereignty and Submission

If Spain seeks to learn from Hungary’s model, the lesson should be clear: sovereignty requires equilibrium, not escape. Hungary’s connectivity succeeds because it turns multipolarity into leverage. Spain’s version risks failure because it turns uncertainty into dependence.

A balanced foreign policy can maintain friendship with Washington while cooperating with Beijing. But a policy born from disappointment with the United States and admiration for China will quickly invite retaliation from one and domination by the other.

Madrid may find itself targeted by Washington’s scrutiny and, worse still, taken hostage by Beijing’s economic instruments of influence.

Spain’s royal visit to China is more than diplomatic theatre; it is a mirror of Europe’s confusion. It shows how even the oldest Western nations can lose confidence in their own orientation when confronted with global fragmentation.

Yet the remedy lies not in mimicry but in memory.

If Madrid wishes to seek understanding with China, that should be welcome. Yet, in an age of new rivalries, Spain should also remember where its destiny lies. The Iberian gaze, when truest to itself, has always looked Westwards—to the Americas, to the Atlantic, to the world of shared faith and liberty that Spain helped to build.

Turning East may promise trade; looking West still offers civilization. And that, ultimately, is the Spanish way.

Related articles: