Tünde Fűrész is an economist specialising in law. She is married and is the mother of three daughters. Since 2010, she has been an active originator of Hungarian family policy, first as department head, then as deputy secretary of state responsible for family policy and demography. As a Ministerial Commissioner, she was responsible for the transformation of the Hungarian crèche system. Since December 2017 she serves as President of the Maria Kopp Institute for Demography and Families.

How would you summarise the role of the Mária Kopp Institute in Hungarian society?

The mission of the Mária Kopp Institute for Demography and Families (abbreviated as KINCS in Hungarian, which means ‘treasure’) is to support Hungarian family and population policy. As a governmental background institution, we carry out research and analyses that can form the basis of pro-family and demographic measures, thereby contributing to the family-friendly and harmonious functioning of society and the survival of our nation. We started our operations in 2018, the ‘Year of Families’, to contribute to the birth of all children being wished for in Hungary, finding the most appropriate and effective responses to our demographic challenges as well as making families maintain the nation stronger while making them grow even more.

Does KINCS primarily serve the government’s policy or the nation as a whole?

Family policy and demography are not just one of the national strategic issues, but a common mission that defines our future in Hungary and in the world in the long term. Without laying down the foundations and promoting family-focused political thinking, without the protection and support of families and without a proper understanding of possible pathways to a demographic turn, it is inconceivable to build our common future and halt population decline. Our most treasured ones, our children, are the key to our future, thus we believe our mission is supporting and protecting families in having and raising children. At KINCS, we work for the accomplishment of these goals to serve every family.

According to its charter, the Institute was founded in 2017—years after the conservative government announced a turnaround in population policy. In what state did you find the Hungarian society at the time of the foundation of the Institute, and what state is it in today compared to that?

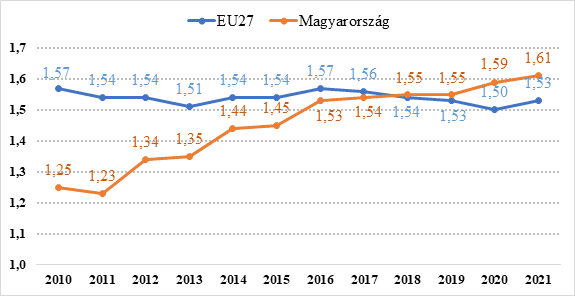

Indeed, the Mária Kopp Institute was founded at the end of 2017 and its operation began in 2018. 2010 marked a watershed in Hungary, bringing about a family-friendly turn in policymaking—that year marks the beginning of the decade in which families have become the nation’s most important asset. The intervention was already urgent around 2010 since that period marked a historic low both in terms of the number of marriages and the desire to have children. By 2017, the fertility rate had increased by 20 per cent and the number of weddings by 40 per cent. And, thank God, this trend continued, as

in 2021, the fertility rate was 30 per cent higher, and the number of marriages doubled compared to 2010.

We have jumped to top third among the EU countries in this regard from being the Union’s tailenders. Due to the economic uncertainty caused by the pandemic, the war and the failed Brussels sanctions, these numbers fell slightly in 2022, but if we look at the current situation from the perspective of a decade, the trend is certainly upward.

What has changed in general?

Due to the consistent and active, work-based family policy of the government, a family-friendly turn was realised, providing stability to Hungarian families for four governmental terms now. From the point of view of having children and raising children, predictability and stability are great values. So, it is important that cutting family subsidies in Hungary is not at all on the agenda. Instead, the government introduces new family support measures every year, even in the difficult period we are all facing now. Thanks to this continuous expansion of family policy, 200,000 more children were born in Hungary in the last decade than would have had polices remained the same as in 2010. The most recent census data clearly shows that

the number of Hungarian people in their twenties and thirties, in childbearing age, has decreased, but the number of children under the age of 14 has not changed.

In 2022, there were still 1.4 million children under the age of 14 in Hungary—just like in 2011, despite a 20 per cent decrease in the number of women of reproductive age. These figures clearly show that in Hungary, having children, a family, and being married are values, and a family-friendly attitude has become self-evident by now, as our surveys confirm.

What family support measures are currently in force in Hungary?

In international terms, Hungarians can be considered a definitely family-friendly nation, and this attitude is the basis of our family policy innovations. Family policy measures are set to provide support for all life situations so that everyone can find the most suitable for them.

Last year, the government spent 5.5 per cent of Hungary’s GDP on family support,

meaning that in comparison, Hungary spends the most on family support within the European Union. Since 2010, the family policy has developed like a tree, growing more and stronger branches in the form of increasing and effective measures. Most subsidies encourage families to move forward using their strengths and work. The family policy helps those who work and bring up children—thereby engaging in activities useful for the community at large—to be financially better off than those who do not. That is why the multitude of measures aimed at the balance of work and family, primarily supporting and giving priority to mothers, are given a special role.

In addition, the promotion of home creation is in the spotlight of family policy, since based on our research, home is the second most important factor necessary for having children. The flagship of the home creation programme is the ‘Family Housing Subsidy’, to which a discounted loan, mortgage loan waiver in case of childbirth, as well as tax exemption, VAT exemption and reduction of notary fees are also linked. Among the most popular measures is the baby-expecting subsidy, which has been used by more than 210,000 families since its introduction in 2019. Thanks to the family housing subsidy programme, one in five families with children could move into a new home, and one in four could renovate their home. Last but not least, family personal income taxation now benefits practically all families with children.

These are remarkable financial and taxation-related concepts. How about those related to the well-being of the Hungarian families?

The welfare and physical and mental well-being of children is also a priority area of family policy, which is served by measures such as the development of the nursery system, compulsory and free kindergarten from the age of 3, the discounted or free meals for children, free textbooks in schools, daily physical education or religion and morals class. After the foundation of KINCS, the Family Protection Action Plan was launched in 2019, followed by Hungary’s largest home creation programme in 2021. Both large-scale sets of measures significantly increased the willingness to have children and the welfare of families. Thanks to measures such as the baby-expecting subsidy, the family housing subsidy, the family tax benefits, personal income tax exemptions, the car purchase support for large families or the home renovation subsidy, the standard of living of many hundreds of thousands of families increased, while more children were also born.

In addition to the existing forms of support, starting January 2023, the government introduced new family support measures. Could you please describe these?

The system of family taxation was further expanded, as women under the age of 30 who decide to have children do not have to pay personal income tax (in addition to mothers with four children and young people under the age of 25 are also exempt from paying personal income tax). The student loan system has also been extended: if a woman under the age of 30 gives birth or adopts a child during her higher education studies or within two years after their successful completion, one hundred per cent of her outstanding debt is forgiven. In addition, from January, families raising a chronically ill or severely disabled child can take advantage of an additional tax discount in addition to the existing discounts.

How about childcare benefits? Could you please summarise the actions taken in this regard?

The amount of government support for childcare has also increased: the infant care benefit provided for the first six months after birth amounts to 100 per cent of the previous salary since 2021. The amount of the child care benefit, provided from the age of six months to the age of two years of the child is being increased parallel to the minimum wage, therefore compared to 2010, its amount has already increased more than three times.

Above we heard about the measures helping the younger generations. How about the older ones?

The role of grandparents is definitely important in families. The government policy assists via many opportunities that the different generations can be present in each other’s lives as much as possible. An example is the Women 40 programme, also called the ‘grandmother’s pension’ by making use of which 350,000 women could have retired after 40 years of employment.

Elderly people can also take advantage of the option of applying for a grandparental childcare benefit,

meaning that based on the family’s decision, even the grandparents can go on parental leave.

Are these measures effective in an international comparison?

Hungarian family policy serves as a model for several European countries. Many are interested in the Hungarian policy solutions, the elements of which have already been adopted in several countries, for example in Poland, Italy, Latvia and Romania. In the USA, the Hungarian model of student loan waiver, which in Hungary is linked to the birth of a child, is highly valued. The domestic family policy has more and more friends in the world—even countries in the Far East have shown interest in adopting some of those.

What might be the reason for this success?

Most probably because—contrary to the trends of the developed world—the fertility rate has increased in Hungary not resulting from migration, but as the result of a predictable and active family policy.

In 2021, Hungary was above the EU average with a fertility rate of 1.61. This is a significant increase compared to the figure of 1.23 in 2011. According to the Hungarian Central Statistical Office’s data, in 2022 the number of births decreased by 5.0 per cent, the number of deaths decreased by 13 per cent, and the number of marriages decreased by 11 per cent compared to the previous year. This means that the estimated value of the total fertility rate per woman was 1.52 compared to 1.59 in 2021. Do you think this is a trend reversal or a temporary fluctuation?

We hope that it is only a temporary fluctuation, which is mainly caused by the uncertainty around the war in Ukraine and the difficult economic situation caused by the Brussels sanctions. Economic stability makes it possible for family policy solutions to be effective. If there is a downturn, predictability and the sense of security decrease, which are important factors in having children. The favourable demographic indicators measured before the current crisis were in line with the prosperous outlook of the Hungarian economy. And, on the other hand, naturally, some people decide to wait and postpone their plans to have children in more difficult times.

What are the major difficulties right now?

Unfortunately, it is still a Hungarian feature that the number of people of optimal childbearing age is decreasing. This means that proportionally fewer women should give birth to more children to ensure that the number of births remains at the same level. That is why the new family policy goal of the government is so important: the administration is on a mission to convince the youth to have children earlier.

If young people have their first child in their twenties, there is a greater chance that siblings will follow in the family, so we can approach the desired fertility rate of 2.

Young people must be helped to create the financial conditions for starting a family so that they dare to commit.

‘The mother shall be a woman, the father shall be a man’, states the Fundamental Law of Hungary. According to some, the constitutional settlement of this fact is exclusionary towards sexual minorities. In connection with this, even a counter-campaign was launched, the slogan of which was ‘Family is family.’ Are we talking about positive discrimination or exclusion when, among competing family models, the legislator prefers models that contribute to increasing the fertility rate?

Hungary and the overwhelming majority of Hungarian people have repeatedly expressed it that they consider it important to protect European Christian values. This includes the protection of the institution of family and child protection as well. Attacks on family policy, on the Fundamental Law and now on the child protection act are always ideological attacks. Right now, Hungary is against LGBTQ propaganda. For us, the protection of children comes first—in the constitution, in the family, in the kindergarten, and in the school. In general, policies are often characterised by positive discrimination in some way, and every state has the sovereign right to prioritise which groups of society are to be focused on. Interestingly, very few people in the Western world think that, for example, large families can also be a vulnerable type of social group, because raising many children puts a much greater financial challenge on parents than raising fewer.

What are the indicators of vulnerability and what are the measures to tackle these?

First of all, the risk of poverty. Fortunately, the risk of poverty among large families has halved in Hungary, but the rate of reduction was almost the same for single-parent families. This clearly shows that the Hungarian family policy benefits all parents raising children. It is also worth highlighting that the Hungarian family policy provides many subsidies even after the foetus, and the unborn child, thus protecting the children. It can also be interpreted as a type of positive discrimination because the goal is to save human lives in vulnerable situations by providing financial support to their parents. In Hungary, according to our understanding, a child is a value, a real treasure. This is stated in our Fundamental Law and the Family Protection Act when it states that ‘Human dignity shall be inviolable. Every human being shall have the right to life and human dignity; the life of the foetus shall be protected from the moment of conception.’ In the same way, we try to protect with the tools of the law the traditional family values that are under attack. For this reason it was necessary to formulate and define in the Fundamental Law that ‘Hungary shall protect the institution of marriage as the union of one man and one woman established by voluntary decision, and the family as the basis of the survival of the nation. Family ties shall be based on marriage or the relationship between parents and children. The mother shall be a woman, the father shall be a man.’

Of the children born alive, how many grow up in families, and how many receive state care?

Thanks to the strong support for childbearing, the simplification of adoption and given the fact that state care has become more family-friendly, less than 1 per cent of minors in Hungary—20,000 children— receive specialised child protection care, and today 70 per cent of them live in families, with foster parents. It is a positive trend that three-quarters of the children born now have married parents. This is a great step forward because previously the parents of only half of the babies born were married. In addition, it is also noteworthy that while children were involved in three-quarters of divorces, today this is true for half of divorces.

Same-sex adoption is prohibited in Hungary. It is obvious that children who are not adopted end up in state care. With what measures is the government working to provide suitable conditions for these children? What recommendations does the Mária Kopp Institute make in this regard?

The government is building a family-oriented child protection framework. For this reason, foster care has become an employment status in recent years, and in 2020, the government introduced the child care fee for foster children’s parents. Of the thousands of children living in child protection institutions, only a few are available for adoption, even though they too need affirming family love. Foster families are a chance for them. By the way,

family support benefits can be claimed for adopted children in the same way as for biological children.

This policy decision of the government also expresses that every child in Hungary is a treasure. One ins six couples in Hungary struggles with infertility problems, so for them adoption can be an opportunity to start a family.

The migration of Hungarian people to foreign countries continues to be a serious challenge. In this regard, KINCS was able to provide good news recently: between 2011 and 2021, 173,000 Hungarians returned to Hungary, mainly from Germany, Austria and the United Kingdom. The annual number of returning Hungarian citizens gradually increased between 2010 and 2018, from 1,575 to 23,401, and since 2018 has stagnated at around 23,000. What is the reason for this? What else could be done to encourage Hungarian citizens to return home?

I am convinced that the generous family subsidies available played a big role in the return migration between 2018 and 2021. Also, the increase in wages, the increasing number of job opportunities that offer a higher standard of living, and the safe and predictable environment. And, certainly, the pandemic was a key factor in 2020/2021 as well. During the left-wing government, three times more people left Hungary than returned. In 2018, the trend reversed and there are more and more families with children among the returnees. For even more people to be able to come home, it is important to break down all the administrative obstacles connected to resettlement, to provide extensive information and, above all, to offer as many attractive opportunities related to the labour market and family life as possible. For us, every Hungarian child is a treasure, no matter where they are born in the world. They all belong to the Hungarian nation, which is why we try to tie them to the motherland from the moment of birth. For example,

under the Umbilical Cord Programme, parents can receive maternity support from the Hungarian state for a Hungarian child born anywhere in the world

and can take out a ‘baby bond’ for the child. Thereby, the Hungarian government would also like to contribute to Hungarian families within and across borders to grow, prosper and strengthen.

(Editorial note: The baby bond is a state-granted one-time support amounting to 42,500 HUF and is available as a start-up allowance, which is credited by the Hungarian State Treasury (Magyar Államkincstár) to a start-up deposit account opened for the child. Until the child reaches the age of 18, the amount deposited in the account is increased annually by the Hungarian State Treasury with an interest rate subsidy equal to inflation. The savings accumulated in this way can be disbursed once the child is over 18 year-old.)