This article by Kálmán Tábori was originally published in the Hungarian Chronicle in 2021.

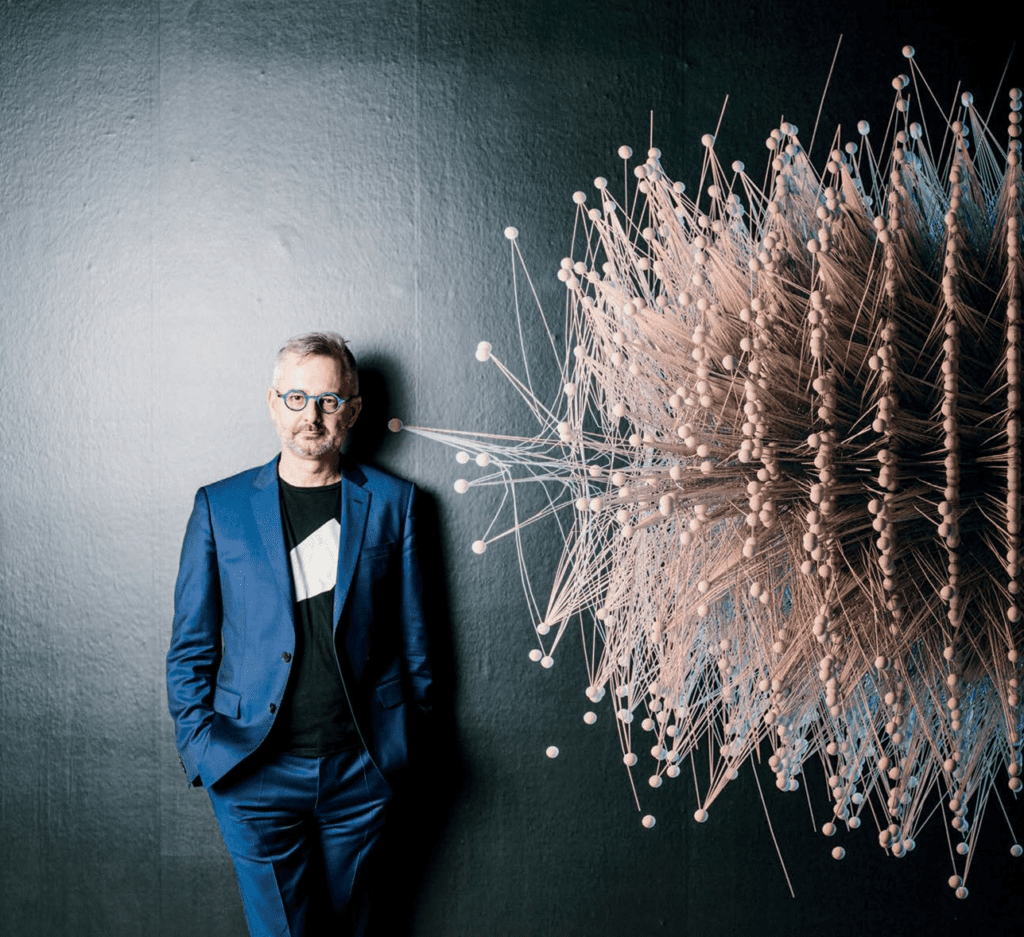

It is often said that everything is connected with everything, but there is someone who actually proves this maxim. We discussed the patterns discernible in his own life with Albert-László Barabási, the internationally acknowledged network scientist.

Albert-László Barabási was born in Karcfalva, Transylvania, in 1967. He attended college in Bucharest and continued his studies in the physics department of ELTE. He received his PhD at Boston University. Today he is a lecturer at Northeastern University and the head of its Center For Complex Network Research, and also teaches at Harvard. By reading his popular books including Linked and The Formula and visiting his exhibitions, anyone can get a glimpse of the secrets of networks.

***

Have you been pulling your hair recently?

Why?

Because of the pandemic. Didn’t you think: we said this would happen?

On a professional level we had lived with the thought of an epidemic. My colleague Alessandro Vespignani has been studying how epidemics spread for fifteen years, and he predicts where and when they will appear. So, we had previously been aware of the looming problems. If my colleagues and I were angry or sad at all, it was because some leaders behaved incompetently at the beginning, especially in America. They did not take measures that would have been necessary for us to be able to get through it more easily.

You foresaw the pandemic. But was it also possible to foresee the consequences?

No, because the consequences always depend on what the virus is like. And we did not have a clue about that in advance. Or about how society would react to it. What we were able to say accurately in January last year was how Covid would spread, where it would appear, and where it would become strong, if the initial inactivity continues. The prediction is not about this any longer, but about the expected results of interventions, or about the combination of measures needed to ensure that the economy functions properly and to hold back the spread of the virus at the same time.

When you as scientists foresee tendencies or events affecting the entire globe, such as the Covid pandemic, does it trigger fear on the personal level?

Strangely, it does not. Although it is also true that I have never believed in apocalyptic predictions of society breaking down.

In an interview you said the pandemic is nature’s way of giving us the finger, saying it could be a lot worse.

And this is true. Because what is the most unexpected aspect of this pandemic for all of us? It is the fact that it has five days to spread without symptoms. Earlier, virtually all viruses spread only when they were symptomatic. In that respect Covid is nasty and sneaky, playing foul: it manages to spread without us noticing that we are sick. Luckily, however, it has not been too dangerous. It still is not. Just consider for a moment, if it had come with 15-20 per cent lethality like Ebola, for instance, then the situation now would be completely different. This is why I am saying that it gave us a good scare. There has been a heavy toll, but not as heavy as it could have been in the case of another virus.

So all this was like an exercise?

Yes, and I think the majority of people around the world reacted in a disciplined way. No major breaches have occurred. Virtually everybody has accepted that the virus is here, it has to be taken seriously, and everybody did, on the level of the individual, everything that had to be done. For me it was quite impressive to see no signs of partying on New Year’s Eve when I walked round downtown with my dog. And no apocalypse befell us of the sort envisioned in movies in such situations. Regarding the political sphere, I think it always learns from crises. Every country and every international organization will build their own pandemic-forecasting methodology. In the same way that in the past the whole world was prepared for the eventuality of an atomic war, pandemics will have to be expected going forward. Someone I know founded a company a few years ago to convince insurance companies, based on available data, that they should offer pandemic insurance. His company went bankrupt only a couple of months before Covid, because he was told by everyone that there was virtually zero chance of a pandemic. Ironic timing! Now we will think about it differently.

Have you suffered any personal loss due to the pandemic? Anything you had to let go?

We had this discussion in the family a number of times. Our experience was that we became a lot closer, we spent more time together, and we ate more healthily as we cooked at home. I even had more time for work, somehow. Considering my private life, it would be difficult for me to say what was wrong in the whole thing. What’s more, I believe humanity and the planet needed the stop caused by the virus. As in the lives of academics there is a sabbatical every seven years, it could also be useful for society to be able to say that from time to time we should close ourselves down for a couple of months to recharge. It would be healthy for both the environment and the individual. Only if we could properly prepare for it, naturally, to avoid all the suffering and side effects Covid has caused.

Can it also be predicted with scientific methods how the individual has been changed by this pandemic in terms of health, mental health, and social connections?

Now, these are all different areas. Covid is guaranteed to stay with us as a subject of research for years to come, as it has been such an ordeal for mankind that it cannot be neglected. If we only consider those engaged in education, we can say their next twenty years or the success of their entire professional career may be determined by what happened. Those who were unable to study online due to their age, or did not have the financial or technical means to do so, people who did not have access to a computer, for instance, may be faced with huge problems. They will feel life-long after-effects. In addition, such a gigantic heap of data has been gathered on society, biology, the processes of spreading the virus, and in many more areas, that science will be engaged in processing and understanding it for the next twenty years. There will certainly be changes in our lives. This process, however, has still not concluded, it is an open subject. We may be able to discuss what exactly happened in, perhaps, about five years’ time at the earliest.

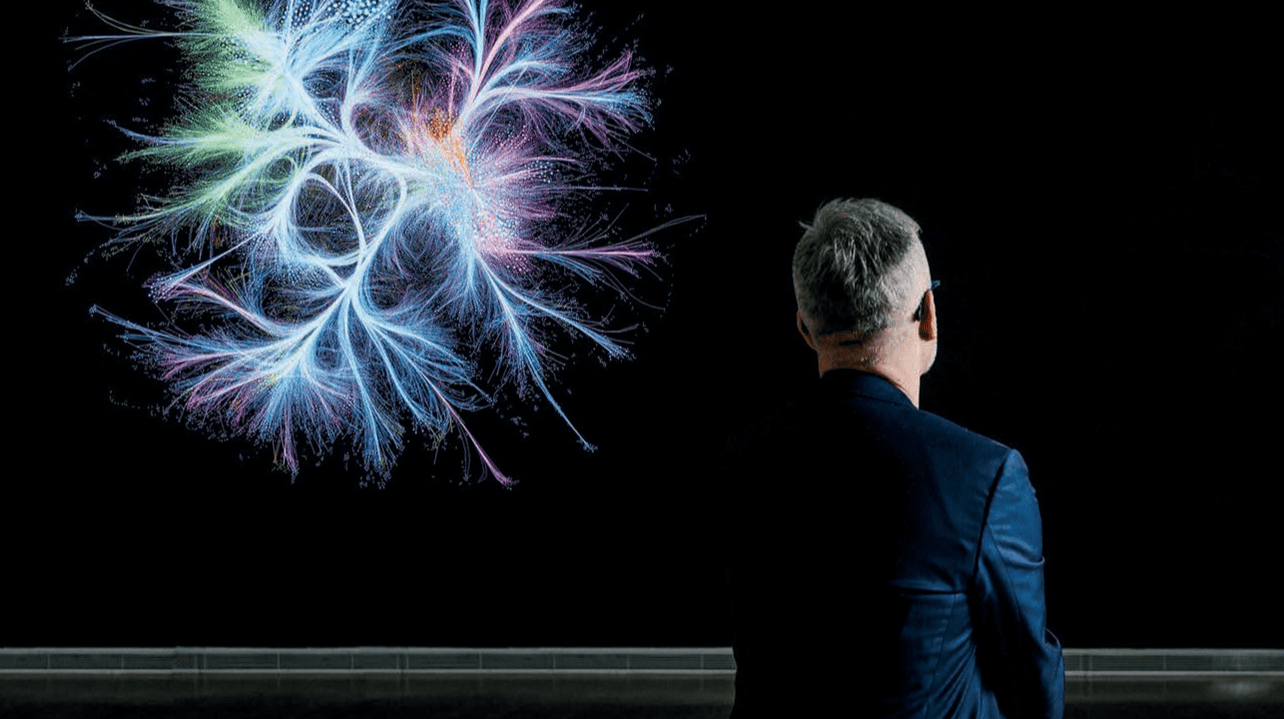

In the Ludwig Museum, the results achieved by the Barabási Lab over the last twenty-five years are on display. What can we learn about the lab, you, and the world from this exhibition?

These are big questions! What is learned depends on the viewer, and the angle he or she approaches the works from. Essentially, we tried to present the process our lab hosted in terms of network visualization. Interestingly, the first item that was a result of my thinking in and about networks was not an article but a visualisation. And this has stayed with us all along, since whenever we undertook to work on a research topic—either human movement or the structure of the brain, or the connection between intracellular networks and diseases—in addition to our research, we always visualized whatever we were doing. Our aim was not to arrive at eye-catching images but rather to understand the processes we were studying. These pieces were completed mostly because I tend to think visually. The visual structure of the language of networks had been interesting for me from the very beginning, and visualization was also necessary for us to be able to understand these systems.

Can the pieces on display be regarded as works of art?

That is up to the visitors to decide. For me it is not important. The motivation behind them is scientific at its core: it is part of the process of discovery.

But Albert-László Barabási the artist is also in them, isn’t he?

Of course, he is. I wanted to become a sculptor when I was young, and when network science was starting out in my lab, I was attending art courses in college. It is quite acceptable in art that creative minds draw inspiration and adapt certain forms from science, be it a statue, a painting, or anything else. These works, however, are the results of a reverse process, as my interest in art influenced how we would represent science.

What was the first question to be raised in network science that you wanted to answer, which kick-started this field in the mid-nineties?

There was no specific question. Science for me is always about discovering new fields. I felt there was an interesting problem: the entire world works like a network, but science was not really concerning itself with that. When I started to read the literature, I realized that there were smaller sub-fields, such as graph theory in mathematics, or the social-network school in sociology, which had been working on the subject. But nobody had undertaken to deal with the big question: what is the structure of networks that can be found in nature? No toolset for this existed at the time, either. I saw an opportunity in an unsolved, uncharted area on the map of science where it was worth straying in the hope of finding beautiful mountains, valleys, and forests to explore.

You have said several times that for five years your efforts in network science were in vain, that you started out with a series of failures between 1995 and 2000. What happened during those years?

I have been thinking about networks since December 1994, and the first five years were indeed frustrating, because I was not really able to publish or to start off with my theme. I did not have an appropriate amount of data, and I did not have the necessary financial resources. The biggest issue was that I was unable to explain the subject to the scientific community, to make them understand why it was important. This is only natural, after all, since so long as we do not make discoveries, we do not have the language to communicate them, either. Then in 2001 we wrote an article summarizing the results with Réka Albert, my PhD student. This practically defined the structure for network theory. Almost all books, textbooks, and articles build on it today.

So you have experienced success as well as failure. How can one bear the latter?

I think failure can be a strong force of motivation. The fact that I worked with networks for five years whilst I was unable to publish anything shows I do not easily give up. Many believe that successful researchers are geniuses. I would rather say successful researchers are not like racehorses which run beautifully and fast, but are more like mules. They can stick to a topic and carry on with it until they find the language, the subject matter, or the question that makes it possible for them to present their ideas to the world. During those five years I did not think there was any problem with the world of scientists just because they failed to understand why we wanted to work with networks. We had to advance to the point where the first few discoveries were mature enough to be made, through which we managed to explain what it was all about.

Does this unshakable rock-solid faith come from you being a Székely?

It is true that the Székely have a certain degree of stubbornness, which I also happen to have. Scientifically, a controlled study would be required in which a Transylvanian Hungarian and a non-Transylvanian Hungarian are placed into the same environment, and we would see whether they end up in the same place—I am sure they will not. So, I don’t really know where it comes from, but I certainly nurse topics for years, waiting for the right moment and the right associate to unwrap them with.

Can you define a ‘Barabási Constant’, something that has followed you all through your life and determines your activities?

Yes, such internal laws do exist. I think choosing the subject matter is the most important for me. For instance, I do not touch topics where strong professional knowledge already exists, because I do not think that I or anyone in my lab could be smarter than those who are already working on it. So, if an area is already active, I do not think we have a place there. The other crucial point for me is to find areas where data has just begun to flow, and our network- and data-based toolset is suitable for taking the next step. I always look for opportunities where a new field could be established in the next couple of years.

Is this something characteristic of your entire life?

You see, I received my PhD twenty-five years ago, and I have been working as a researcher ever since. This is what has defined me so far. I do not think it will change going forward.

I am asking because I saw a biographical documentary about you in which people who knew you from the old days all said you had not changed a bit since you were a kid: you had always been an open-minded renaissance man who drinks in knowledge from different spheres including literature, science, and art.

I call this curiosity.

‘In addition to speaking the language, I wanted them to also soak up the culture by way of the community’, he explains the reasons for sending his children to school in Hungary. The researcher also spends sixty per cent of his time at home, in Hungary.

Which is not characteristic of every scientist.

I think there are two types of scientists. One is the golfer who is hitting the ball until it goes in. The other one is the tennis player who needs to return every ball. I think I belong to the latter category. I have been working on several topics simultaneously from my student days. I relax when I can put down the current scientific question I am working on and go to a museum to marvel at the works on display. It activates a different part of my brain. The part making calculations all the time is switched off on those occasions.

It is as if this universal approach is also what led you to networks.

It is easy to see it like that post factum. Perhaps what I said earlier is simpler and more honest: I did see a professional opportunity in it. I certainly bring a wide range of interests into the picture. As I said, I wanted to become a sculptor when I was a student, and I also took to writing when I was young. When I attended college in Bucharest, I published articles of popular science in the magazine Hét [Week] regularly. The fact that I am active in art, science, and I write, and I also admit that I am doing all this, is because I do not define myself as a researcher, but rather as an intellectual. In America it is not at all understood what an intellectual is. But in the European environment, and particularly in Transylvania, it is not unheard of. When I grew up, during communism, a person with a college degree had to be an intellectual. It was expected of him to go to the theatre, to attend cultural events, and so on and so forth. My father was a historian, but he was equally interested in UFOs and the fine arts, whilst he regularly performed on stage as a singer for ten years. My mother was the same, she taught literature and concluded her career as a director in a children’s theatre. It was quite acceptable in the family to switch careers. I am not switching careers, but within science I am switching between topics, since I’m not ashamed at all to apply the toolset I worked out on different subjects.

In a biographical film your mother said of you that it had been apparent even when you were a child that you knew you were the best. Is this true?

Mothers are always convinced that their child is the most beautiful and smartest person on earth. My mother was also my form master at school, so she not only saw me as a child but also as a pupil. But no, I have never felt I would be better than the next guy professionally. I am rather happy that science is not like sports where the better one wins. In a competition like that I would always lose.

You said you always try to avoid competitive situations…

In the course of my career there have always been people I looked up to, because they were better than me professionally. But science is not about our problem-solving abilities, it is, rather, about asking the right questions. I think I have simply become someone who raises questions well. I always tell people coming to my lab, you will not learn any techniques from me, you already have what it takes. That is why we hired you. What I will be helping you with is the selection of topics and how we process the subject matter in a way that resonates within the scientific community.

‘It is impossible to detach yourself from your roots, and one should never attempt to do so. I do believe that we have to actively take on our past’

I am in the middle of your book Bursts, which is different from the rest of your books in that it is unusually personal. It is quite clear what a solid foundation your homeland has been in your life.

You are right. It is made more personal by being less scientific; it is rather focused on trying to find my past. It is impossible to detach yourself from your roots, and one should never attempt to do so. I do believe that we have to actively take on our past. Last week we were in Transylvania with the family. We go back once or twice every year, because I think it is important for my kids to understand and get a feeling of where we come from. My past is not only my childhood, it is also my life in Budapest, my consultant project leaders, and America, where I studied. This is all living material inside me, and it needs to be respected, I have to give it what it deserves. In Bursts, I tried to reflect these things, in one way or another. I do not know if I would ever write a similar book again, because I feel I managed to conclude certain things for myself by writing it.

Where is home for you now?

This is interesting, because it is totally in Budapest now; I am here physically, with my soul, and all my senses. But as soon as I am on a plane, my brain is already in Boston. I immediately switch over, and the processes that are important there are started up in me right away. When I land there, I feel at home in Boston. And this is true the other way round as well.

And what about Csík?

My wife used to say that I am a different person at all three places, but especially in Transylvania. My whole character changes dramatically as I adapt to each environment. In Transylvania, for instance, I am simply unable to work, the environment totally penetrates my being, motivations and priorities are changed completely. So when I head for Transylvania, I tell the guys in the lab, ‘I will be offline for a month. Call me only if the house is on fire’. It would be useless for me to try to follow ongoing projects from there, I just do not care about anything when I am there. I am like a chameleon, really. I always strive to be surrounded with things that fit the location, and to close out everything outside this circle to avoid anything that would interfere with the mode of existence I am in.

Reading Bursts, I experienced many surprising twists. One of them was when you manage to convince me that our private sphere today needs to be protected at all costs, and then you describe village customs in Transylvania, the christening, the wedding, and the funeral. And I realized that after all it is a basic human need to share as much as possible about ourselves, to ensure that we are known in the community…

This is exactly the great dilemma of our private sphere. There is no humanity if we do not belong to a community. For becoming part of a community, it is necessary to share ourselves with, and to be accessible physically and emotionally to, one another. We have to give something up—consciously. And what mankind has recently been struggling with is exactly the question of where we should draw the line. I do not think there is a universal answer to this. And it is not a good solution if decision-makers want to find a global answer, because every community has its own internal needs regarding where to draw the line. The challenge is, for every community, to find the right balance.

The title of one of the pieces in the show in Ludwig Museum is my twenty-first century. Is it possible to already see what the new twenty-first century will be about?

I feel this century began in March 2020. The piece you mentioned shows that we processed movement data in New York City before the pandemic and after the lockdown. You can see the unbelievable vitality which had characterized the city, and then you see the moment of lockdown, and that a new structure, a new order evolves in a matter of weeks, as the city has to function. The twenty-four-hour and one-week cycles that had formerly been observed returned, but at a much smaller amplitude. A new normalcy was born, different from what we used to have, and most probably it will never be the same again. We re-learnt a lot of things and, I think, began to feel that the way many things had been before was overheated. I am convinced that lots of things that used to be important in my life will not be so important any longer after what has happened. And I don’t really miss them. How it will look like going forward is a difficult question. There is no scientific answer, but what we are experiencing now feels like a defining moment. As Henry Kissinger says, a crisis should never be wasted. The big question when it comes to our world as a whole is what can be built now so that in the long run the outcome is something positive rather than negative, and we don’t waste the opportunity.