This is an abridged version of the original interview published on 777blog on 11 March 2023.

Tom and Lívia Schachinger are active members of the Hungarian community in New Brunswick, New Jersey, while also frequently visiting events of the St. Stephen’s R.C. Magyar Church in Passaic, New Jersey. However, for a long time, we didn’t have the opportunity to talk. Over time, I heard that Tom became the district scout commander. Later, I learned that Lívia is an award-winning folk dancer and runs a lángos-making business, in addition to baking Hungarian cakes for order. Tom has a somewhat ‘exotic’ job as an engineer at a nearby oil refinery, and Lívia is constantly volunteering in the Hungarian community, because, as she says, she ‘wouldn’t just sit…’

***

Born in the USA — Tom’s Story

Tom’s parents were born in Hungary. His father immigrated to America in 1970, hoping for a better life. During his military service, he learned where border control was weaker, and he and his brother agreed to escape together. But in the end, his brother changed his mind at the last minute and decided to stay. Thus, Tom’s father set off alone. First, he arrived in Austria, then made his way to America, initially living in Virginia, and later moving to New Jersey to join some acquaintances because, as he put it: ‘There were many more Hungarians there, and they were much more close-knit.’ He met his future wife by correspondence, and in 1979, Ildikó also immigrated from Hungary to America to marry him. Later, Tom’s father returned to Hungary, where he retired, but according to his son, he was always very proud of the Hungarian family he built overseas.

Born in 1980 and raised in New Jersey, Tom has fond memories of his childhood, especially of the Hungarian weekend school in Passaic, New Jersey, at the time led by Emese Kerkay, where his mother also taught. ‘My best friends were from that Hungarian school—they were the ones who convinced me to join scouting, and we’ve kept in touch ever since, especially now that we’ve moved back to New Jersey. Folk dance was also present in my life throughout. I first encountered it at the Hungarian weekend school, where Emese’s son, Béla, also taught us small choreographies. I even performed solo once—we weren’t professionals at all, but we loved it. When I became a Regös scout, Ildikó Hajdú-Németh taught us palotás (a historical Hungarian court dance), and we absolutely loved that, too. I have so many fond memories of Passaic…Even my job is the result of my scout connections from here,’ Tom recalled his childhood memories.

After graduating from the New Jersey Institute of Technology with a degree in mechanical engineering, Tom pursued a master’s degree. It was then that Imre Lendvai-Lintner, current president of the Hungarian Scout Association in Exteris (KMCSSZ) and a group leader for mechanical engineers at ExxonMobil, encouraged him to apply for a summer internship at the company. The internship was so successful that after graduation, Tom worked for years in Washington, D.C., at Exxon. ‘I’m grateful to him, and it makes me happy that my work has significant value for society. Within the mechanical engineering team at the oil refinery, I work on repairing, maintaining, and implementing new technologies for reactors, valves, and pipelines,’ he explained. After two years of office work, where he learned a great deal from the best engineers, he was transferred to a refinery in California, where he could continue his work by putting his knowledge into practice.

On his first weekend in California, Tom was invited to a scout opening campfire, where he met Lívia, who wasn’t a scout at the time. ‘In California, Hungarian scout recruitment is much more important than at our New Jersey troops, where a large number of Hungarian children have been born recently. Therefore, they also invited non-scouts to that campfire. I was 24 years old, I had no car, and I only knew one person, but word spread that there was a “new boy in town”. Suddenly, a very pretty lady appeared in front of me—bundled up like an Eskimo. She already knew something I didn’t—it can get very cold at night by the ocean shore even in the summer. And she told me straight out: “On Wednesdays, you’re coming to our folk dance session. My brother will drive you back and forth.” I liked her confidence, and of course, I gladly went—after all, I loved dancing, and I had time for it. In Washington, D.C., I had learned folk dance from Árpi and Szilvia Kovács—there were 20 girls and only I in the group…I even performed at the Hungarian Embassy, doing a couple’s dance from Mezőség. I really enjoyed it, but I didn’t take it too seriously. I wasn’t paying attention to what I was learning or how—I just did it. But in Los Angeles, the Kárpátok Ensemble, where Lívia invited me in 2006, was a very serious dance group. I had to pay much more attention, which I gladly did. I loved dancing with her, and then things fell into place—we’ve been dancing together ever since…,’ he laughed.

From Hungary to America — Lívia’s Story

At this point, Tom handed the conversation over to his wife. Born in Kaposvár, Hungary, Lívia was 13 years old in 1987 when her six-year-older brother faced a life-changing decision: he would join the army or he would flee abroad alone. Two years earlier, their family had the opportunity to visit America, where their mother’s uncle lived. So, two years later, her brother wanted to immigrate to America, but their parents didn’t allow him to go on his own; instead, they decided to try to leave together. Eventually, they succeeded, but it was quite an adventure. ‘We applied for Austrian visas via two separate requests—first, father and son, then, six months later, mother and daughter. Since there were no computerized systems at the time, no one noticed the connection. When everyone had their visas, we set off as tourists, moving together with a tourist bus, but with our own car. The route went through Czechoslovakia. But when we crossed the first border, we didn’t get the required stamp. At our second border crossing, we were told to turn back to Hungary and cross directly into Austria. All the while, I thought this was a birthday trip for me, so I had no idea why my parents and brother were so nervous,’ she recalled the beginning of the adventurous escape from Communist Hungary.

‘I’m grateful to him, and it makes me happy that my work has significant value for society’

It was only the next day, after entering the Traiskirchen refugee camp in Austria, that Lívia’s parents revealed the truth to her. ‘I couldn’t process what was happening—all I understood was that we weren’t going home, and I was worried about what would happen to my fish in my fish tank and with my cat…That’s when I started to realize why we sold our downtown apartment and moved to a half-finished house on the outskirts of town shortly before—so we would have money for the journey,’ she remembered with a sad smile. The family spent a year and a half in Austria. After undergoing various medical examinations in the camp, families were dispersed across Austria and placed in refugee camps, where the adults worked illegally, while Lívia attended an Austrian school. Each week, they announced which families could travel onward. Since they had her uncle as a sponsor, they were allowed to immigrate directly to Los Angeles. ‘I still have the document listing our family’s name, allowing us to finally leave. Our time in Austria was tough, especially for a teenager. For example, we weren’t allowed to cook for ourselves—we had to eat what was given in the camp kitchen. But they didn’t care about cleanliness at all, so we were sick all the time. We could only access hot water at designated times, so my dad and some friends “fixed” the water heater, and after that, we always had hot water. No one ever found out,’ she laughed.

The family arrived in Los Angeles penniless and initially lived in a dangerous neighborhood. ‘There was a police officer stationed inside the classroom to watch over the students. I refused to attend that school. Luckily, through our relatives, my dad and brother found work, and we were able to move to a better area, where I finished high school. My parents lived there until they moved back to Hungary several years later,’ Lívia said.

After a few years’ break, Lívia was able to return to folk dance, too. In Hungary, she danced and performed as a member of a local folk dance group. In Los Angeles, she and her brother joined the Kárpátok Ensemble, which had around 50–60 members at the time. At 16, she was the youngest dancer. There was a huge Hungarian folk dance scene in the United States in the 90s. ‘Our ensemble received a lot of support, teachers from Hungary visited often, and we had countless performances all over America. That’s where I finally found my place. If it hadn’t been for folk dance, I don’t know what would have happened to me. They accepted me—and in doing so, they saved me. Our teacher was very strict—we sometimes left practice in tears. And yet, that’s where I felt the happiest,’ she confessed.

At a young age, she met her first husband and left Kárpátok. Later, she heard that the ensemble was going to be dissolved because their leader returned to Hungary, there weren’t enough dancers, and no one was willing to take over leading the ensemble. A university was even planning to take all their costumes, which had been hand-sewn by their group’s seamstress. ‘I talked to my brother and his wife, and we agreed that we can’t let this happen. So, we started dancing again, and we invited our friends and acquaintances to join. We didn’t let them take the costumes and we rebuilt Kárpátok almost from scratch,’ Lívia explained. She took over leading the group when she was 22 and remained at the helm for 22 years. At first, they had nothing—just the costumes, determination, and enthusiasm…and the Los Angeles Hungarian House, which hosted them. ‘The rest, we built ourselves. Since we had no teacher, we taught what we had learned over the past five years.’

‘I couldn’t process what was happening—all I understood was that we weren’t going home’

When Lívia’s first child, Lili (now 23 years old), was born, she founded the Hungarian Mothers’ Club (Magyar Anyák Klubja, MAK) in Los Angeles, bringing together Hungarian families and later directing them toward folk dance. She began teaching folk dance to five-year-old children, forming the Búzavirág children’s group within Kárpátok. She also became a mentor for KCSP (Kőrösi Csoma Program) scholars when it started in the early 2010s. ‘As a mentor, I coordinated with leaders of local Hungarian organizations and arranged schedules for KCSP scholars,’ she explained. Lívia also taught Hungarian reading, writing, and speaking at the Reformed Church every Sunday. But for a long time, she didn’t even know about Hungarian scouting—not even that it existed. Even though the local scout troops’ scout home was just a 15-minute drive from the Hungarian House, she had never heard of them. ‘One summer, they asked me to teach a bottle dance for scouts preparing to visit the Sík Sándor Scout Park in Fillmore, upstate New York. That’s when I first became curious about scouting—mostly for my own children’s sake. By then, I also had a boy, Lackó, now 20 years old. And that’s how I ended up going to my first scout opening campfire in 2000—and then every year after that. So, I was there also in 2006, when Tom appeared as the “new boy in town,”’ she laughed.

A Love Story through Folk Dance and Scouting

While Lívia invited Tom to folk dance, Tom invited her to scouting. They soon started teaching folk dance together at the annual scout leadership training camps in Fillmore, New York. ‘I’ve never planned to become a scout. A friend kept nagging me: “Lívia, you help us so much—why don’t you just become an adult scout?” Eventually, I agreed. I went to the Jubi Camp in 2010, where Tom acted as the largest boys’ sub-camp leader. That’s where I was sworn in and became a real scout,’ she remembered. At the camp, she taught folk dance, but one day, Tom gave her a different task: she had to teach the Soviet national anthem in Hungarian. Seeing my confused look, they both eagerly jumped in to explain, reliving the memory as they spoke over each other with excitement…Every scout camp has a central frame story, and that year, the theme was the history of scouting itself. Each day, a different episode of history was displayed by the scouts. When they reached 1956, Lívia, who knew the Soviet anthem from her childhood, at Tom’s request, taught the scouts and even created pioneer uniforms for them. (Young Pioneers—úttörők in Hungarian—was a youth organization of the Soviet Union and other Communist countries across the 20th century for children and adolescents with many similarities to scouting, but infused with Communist ideology.) The scouts Lívia was working with became so immersed in the play that they genuinely hated Lívia and protested against learning the anthem…In accordance with the frame story, a mysterious figure suddenly appeared during the day and banned the traditional prayer before meals, and everyone was forced to sit in total silence during lunchtime. Then, someone suddenly yelled: ‘Ruszkik, haza!’ (Russians, go home!). Later, when the mysterious figure ordered Tom to be arrested and taken to Siberia to a forced labor camp, the scouts eagerly set out to rescue him during the camp’s adventure mission.

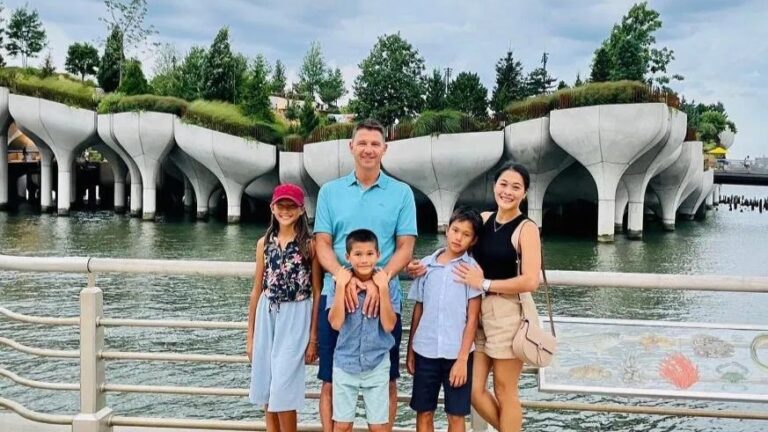

Shortly after Lívia became a scout, Tom, as scoutmaster, needed to strengthen the leadership in the Los Angeles scout troop, so he sent Lívia to officer training camp, where—although she was nearly 40 years old by that time—she learned to adapt to the scout camping lifestyle. In 2012, they got married. In 2013, their first child, Krisztina, was born. From then on, they brought all three children with them to scout camps.

In 2017, Lívia was awarded a Certificate of Recognition for her ‘outstanding professional activities’ by then-Minister of Human Resources of Hungary, Zoltán Balogh. Later in the same year, she was also honored with the Hungarian Gold Cross of Merit by then-President of Hungary, János Áder, in recognition of ‘her work in preserving and promoting Hungarian and scouting traditions in the United States and her devoted efforts in the cultural education of Hungarian children and youth in California’. Besides folk dance and scouting activities, she had a daytime job in a wholesale business selling pet food, a job that sparked her deep passion for healthy pet nutrition. This led her to open specialty pet food stores of her own. Meanwhile, Tom continued working at the local oil refinery, rising to a high managerial level—but increasingly unhappy. Due to the uncertainty surrounding the company’s potential sale, many employees left, and he struggled to communicate with leadership. After much deliberation, he also left the company and became an independent contractor, gaining new and valuable professional connections. Finally, he accepted an invitation from a former colleague to start a new job at an oil refinery in New Jersey. During this time, the couple welcomed their second child together, Tomi.

Leaving California Behind

For a long time, Lívia didn’t want to leave Los Angeles. Neither her deep-rooted Hungarian ties nor her businesses allowed her to consider moving. However, their happiness was tied exclusively to the Hungarian community—and less and less to everyday life in the city. Los Angeles had changed significantly over the years, and they wanted to raise their young children in an environment with different values. At the beginning of 2018, Tom moved to New Jersey for work, while Lívia and the children stayed in Los Angeles to finish the school year.

Tom recalled with a smile that his trial project at his current employer five years earlier had become the same reason he was nowadays working night shifts for two months: ‘Once in every five years, during the winter months, the refinery must be shut down to conduct internal inspection and repair. This requires round-the-clock maintenance, and there must always be an on-site engineer, which is me. It’s a job that demands immense focus and attention to detail,’ he explained.

Eventually, Lívia and the children followed him. However, managing her pet food stores from afar during the COVID pandemic proved extremely difficult. In the spring of 2020, she moved back to Los Angeles with the children. Then, for the start of the new school year, she returned to New Jersey again—and continued commuting back and forth for several months, until she was finally able to sell her stores. At this point, Tom suddenly burst into laughter and shared a humorous story. Before the COVID pandemic, they had brainstormed business ideas for Lívia and decided on dog walking. She obtained a business license and all the necessary equipment, when the pandemic hit and people over-walked their own dogs—they had to close the business before it even started…

Instead, gastronomy became the next venture—initially just as a hobby, but with deep family roots. Lívia’s father ran a bistro (the Tejbár) in Kaposvár, which was the go-to spot for students from the four local high schools with lángos and palacsinta (Hungarian crêpe). Inheriting the family recipes, Lívia launched her own business under the name EuroDough, operating as a mobile vendor. Before that, back in Los Angeles, she had taken over cooking for 50 people every two weeks at the Catholic Church. In New Jersey, she began baking and experimenting with new recipes. Eventually, Lívia’s lángos made their way to Hungarian events in Washington, D.C. She also supplies local markets regularly from spring through fall. At one point, someone ordered a Dobos cake from her, which turned out so well that it became a huge hit. ‘Soon, I was making four to five cakes per week,’ she smiled. As demand grew, she began receiving large-scale individual and organizational orders, often on short notice. For example, this is how she ended up making 150 servings of somlói galuska (a Hungarian dessert) for New Year’s Eve. Some of the leftover desserts even made their way to Passaic for the community coffee after the first Mass of the new year…‘In the Carnival season, I made so many donuts that I swore I wouldn’t bake another single one until next year!’ she laughed.

When they settled in New Jersey, they had to decide which Hungarian community to join. Since Tom’s job and their new home were closer to New Brunswick, where there is a strong folk dance community, they chose that for Hungarian weekend school, scouting, and folk dance, but they took their children to Passaic for religious education.

Falling Back into the Heart of the Community

Although they didn’t originally plan to get deeply involved in the local Hungarian community, they couldn’t avoid it. News of scout leader Tom’s and his folk dancer wife’s return spread quickly in the New Brunswick community. Lívia was immediately asked to start teaching the youngest age group in the Mákvirág children’s folk dance group, which had 90 children at the time. She led the group for four years. Tom was asked to teach the next age group, and he did so successfully that in 2019, they won an award at a folk dance competition in Canada. Due to his demanding job, Tom eventually stepped back from teaching children. However, during the COVID pandemic, when there were no KCSP scholars available in New Brunswick (who normally come to New Brunswick to help teach folk dance), he took over teaching the adult Szilvafa dance group.

Although they had decided to focus only on folk dance in New Brunswick, scouting quickly made its way back into their lives. ‘By then, I had already been a scoutmaster twice, once in Washington, D.C., and once in Los Angeles. I needed a break…Of course, we sent our kids to scouting, but we wanted to stay in the background.’ However, the local scout troop desperately needed adult leaders. So, primarily for their children’s sake, they rejoined the local scout troop. Tom became the assistant commander for the boys’ troop, while Lívia became a patrol leader for the younger girls. They also took over teaching folk dance to the Regös scouts and organized a camp at Solstice Farm, where the boys made sausages, the girls baked bread, they crafted and danced around a Maypole, and selected a Pentecost King and Queen.

After two years, Tom once again scaled back his weekly scouting and Regös activities, while Lívia continued to assist actively. For the past two years, she’s been writing and directing the Nativity play (pásztorjáték) performed at the Christmas Vigil. Last summer, a new responsibility found Tom: he was asked to take on the role of district scout commander. Since then, he has been responsible for the largest district in the KMCSSZ, which includes ten scout troops, including, for instance, those in Boston, Connecticut, New York, Garfield, New Brunswick, Washington, D.C., and Florida. ‘I received so much from scouting as a child—honestly, I even owe my career to it. Later, because of my own children, I wanted to give back even more…That’s why I took on the role of troop commander twice, and now the district commander position as well. I’ve been to so many places, gained countless experiences, and I’ve come to realize something important: each troop has different struggles, but the local troop commanders have the toughest jobs. So, our biggest responsibility is to support them—and I believe that’s why I was asked to take this position,’ he confessed.

Before saying goodbye, they excitedly shared how much they were looking forward to traveling to Hungary for Easter, where their children would receive their First Communion. When I asked why they chose godparents from Hungary, they explained that they wanted to ensure a strong bond between their children and their Hungarian family members. At the end, Tom became emotional as he reflected on his life. ‘My life is a full circle that began at St. Stephen’s Church; my first community memories are from there. After traveling halfway across the world, we are back there every other Sunday, meeting family and friends and raising our children in the same community. Mom has been an active member of the church community for over 40 years—she still organizes church lunches. This, too, connects my childhood to the present…’

Related articles: