The Secretary-General of the Árpád Academy, which was founded in 1961 by the Hungarian Association, carries a monumental family legacy both in terms of public and private life. His father, Dr. Ferenc Somogyi, a university professor and member of the Hungarian Parliament, was forced to leave Hungary in 1945 without his wife and their four children. After five years of hopelessly waiting in the refugee camps in Austria, he immigrated to America. In 1953 Ferenc remarried and started a family in the U.S. His son, Lél, carried on through his involvement in the Hungarian community, while his university student son, also named Ferenc, enthusiastically participates in Hungarian scouting and folk dancing, and even plans to dedicate his future profession to the Hungarian cause, continuing his grandfather’s legacy.

***

Tell us about your father, who was an outstanding young scholar, and a public figure committed to the cause of strengthening families in pre-war Hungary.

My father, Ferenc Somogyi, was born in 1906 in the village of Nárai, Vas County. He completed his secondary education at the Premonstratensian in Szombathely, then studied law and political science, philosophy, history and literary history at the University of Pécs, winning four first prizes and a research scholarship. He was one of the youngest appointed university professors in Pécs. In 1938 he was a social advisor for Baranya County, in 1939 a Member of Parliament representing Pécs, in 1940 a national social supervisor, in 1941 the permanent Deputy Executive Chairman of the National People’s and Family Protection Fund (ONCSA in Hungarian), and later the Head of the National Social Supervision and Public Welfare departments of the Hungarian Royal Ministry of the Interior. He didn’t plan a political career, but accepted it when asked to pursue one, because he was interested in public life, and because his previous university research and work included family protection. At the end of the war everything turned upside down. The whole ONCSA had to flee to protect data records and employees. He was ordered to leave, but his plan was to return soon. However, his wife didn’t want to join him, but stayed in Hungary with their four children, three boys and a girl. I was born from his second marriage in the U.S., when he was already 48 years old—the same age I was when my son, bearing his name, was born.

Did your father ever meet his four children? Did you meet your half-siblings?

Yes, when we visited Hungary after the regime change. It’s a very sad story, but not unique. My father spent five years in a refugee camp in Austria, because America wasn’t in a hurry to accept refugees from those countries that lost the war. He couldn’t return home either. There were many examples of those who tried being executed, imprisoned or sent to the Siberian gulag (effectively Soviet concentration camps), as the communists wanted to destroy the intelligentsia of the ‘old order’ as part of their takeover. My father’s friends talked him out of trying to return to his family several times. He maintained some contact with his youngest brother, but only very cautiously—Western contacts were dangerous for those living in communist Hungary; many lost their jobs or career opportunities because of it. Through his contact with his brother, he tried to bring his first wife and children to America. She didn’t want to leave and had my father declared a war casualty in Hungary, which gave my father the opportunity to start a new family in 1953. My mother, Sarolta Varga, worked as a social worker at ONCSA, and also flew to Austria and then the U.S.

Your father was a theater director, a high school teacher, and the editor of the magazine Vagyunk (We Are) in the Austrian refugee camp. Why did he engage in community building even under such circumstances?

My father was raised in a traditional family and prepared to become a priest. My father’s parents had twelve children, three boys and nine girls, my father being the eldest. According to an ancient Hungarian tradition, if there were (at least) three boys in a family, the first became a priest, the second a soldier, and the third worked the farm property, managed the family estate, and kept contact with the extended family. My father accepted that he would enter the priesthood, but changed his mind at the last moment and chose a somewhat similar vocation as a teacher. His younger brother died in the war. The third stayed in Hungary and held the whole family together. Many who came to America after the war had a similar worldview than him. They thought similarly about family, nation, cultural and linguistic values, their preservation and continuation. In the refugee camp, he tried to carry on his professorial work, teaching and nurturing Hungarian culture, taking advantage of every opportunity there, in theatrical productions, at the school, and through publishing a newspaper. After two years, when they had to accept that they couldn’t return, they began to come to terms with the idea of permanently immigrating to the West. It wasn’t easy. The first groups to leave the camps accepted going to South America and Australia, while the others hoped for North America.

What happened to your father upon his arrival in America?

He arrived in Cleveland in 1950. Most immigrants at that time could only get factory jobs. The first waves sponsored the next ones, also for factory worker positions. America’s policy at the time was to disperse refugees from the losing countries of the war to factories and smaller towns where they would more easily assimilate. They were under strong assimilation pressure, their community life was hindered, and sometimes they were even accused of being war criminals. They also had to find and hold their own place at work and provide for their families. But after the first three or four years, their situation and the perception about them began to change. America recognized that they were good people, and moreover, that several of them were highly educated and informed intellectuals who fled out of necessity, because they didn’t want to live under communism. When I was born in 1954, these changes in attitude and mood were already noticeable.

What specific role did he take on in the local Hungarian community?

Notable people who arrived in Cleveland around the same time, such as Dr. János Nádas and other scholars, writers, and artists began to get together, at first just to keep in touch and talk. This happened quietly until 1956. After that, events accelerated. When the revolution in Hungary was crushed, the Hungarian refugees living in America finally gave up hope of returning home, but their overall reputation improved greatly in the eyes of Americans. They began to act. They felt entitled to speak out against communism and call on governments around the world to do the same. They became part of a worldwide movement, one of the main groups of which was the Hungarian Association re-established in 1952 by Dr. János Nádas, and later the annual Hungarian Association Conference (named Hungarian Congress from 1973), the Árpád Academy, and the Árpád Order. My father became a founding member of these organizations. He was the voice behind the leaders and his writings defined the public profile of the organizations.

What was the purpose of these organizations?

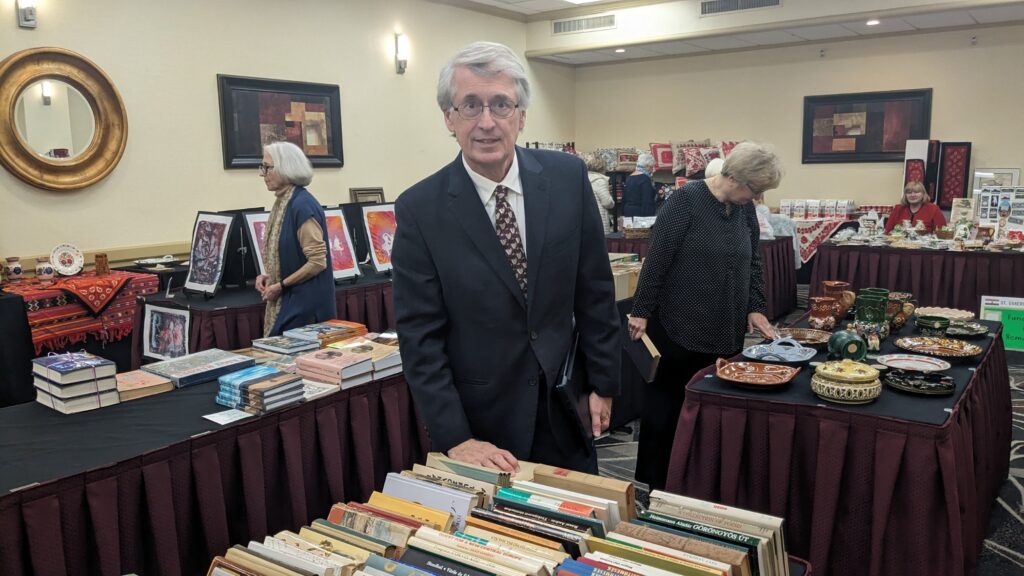

The intent was to bring together Hungarian intellectuals scattered around the world. The goal was for them to meet in person at least once a year. There were many calls, correspondence and partial gatherings, but a big, three-day intellectual experience was also needed. From 1960 onward Dr. János Nádas, Dr. Béla Béldy, and my father began organizing annual meetings. Attendees came from many places, such as Australia, South America, Canada and Europe. In 1962 they announced an annual competition and established awards for the most outstanding intellectual submissions. Gold, silver and bronze medals named after Prince Árpád, made in a goldsmith’s design, were awarded at the same gala dinner where the competition results were announced. The establishment of the Árpád Academy was decided after the 5th meeting in 1965, when the recipients of award-winning works in the scientific, literary and artistic competitions were grouped into a separate organization and declared honorary life members of the Hungarian Association. The goal was to find, take stock of, professionally evaluate, preserve and make known outstanding individuals and their creations reflecting the Hungarian spirit. The first president of the Árpád Academy was Asztrik Gábriel, the vice-president was Béla Szász, the second vice-president was Ferenc D’Albert, the president of the art department was Zita Szeleczky, the secretary-general was my father, and the president of the board of directors was Dr. János Nádas. Among its members was László Gyékényesi, the father of one of our recent awardees. My father was asked to be the chairman of the committee evaluating competition entries. The first gold Árpád medal depicted a stylized copy of the Hungarian Golden Bull, drawing attention to the historical fact that Hungarian constitutional freedoms of the nobility were declared in 1222, just seven years following the English Magna Carta of 1215.

From the very beginning, another idea arose, namely, that Hungarians who excelled in their service to Hungarian churches and organizations scattered all over the world should also be grouped into some kind of unifying organization. The idea became a reality in 1971. The Hungarian Association began to honor those who faithfully served Christian Hungarian national goals and gained fame and respect for Hungarians through their work. The independent group was established as a knighthood to the Hungarian vocation. This became the Loyalty and Vocation Order of the Árpád Association—in short: Árpád Order—, an integral part of the Hungarian Association. This organization honored, among others, Albert Wass, István Eszterházy, Tibor Tollas and many others who are still not adequately recognized today, but hopefully will be one day. In addition, my father compiled and edited the annually published Krónika book series, which chronicled the work of the Hungarian Association and its groups, and contained the programs and lectures of the meetings. In 1982 he compiled a 450-page-long separate who’s who book, which covers the activities of the members of the Árpád Academy, summarizing three decades of work done by the refugee intellectuals. From the 1980s onward, that great generation—including my father—began to age out, though many of them lived to see the withdrawal of Russian troops from Hungary. My father passed away at the age of 89.

Before that he managed to return to Hungary. What did he experience there?

Those who had fled after the war experienced a sense of being lost. The Russians had left, Hungary was liberated, but they no longer found the country they had known. The language and worldview had changed. The communists had successfully wiped out many valuable character traits of the Hungarian people. In recent decades, respect for faith, patriotism, and the importance of family—that is, national values—has partially returned, but in the 1990s it was still at a low point and these values had to be rediscovered. Many difficult questions arose in the minds of the victorious older generation: What will happen to the next generation living in the West? How will they survive as Hungarians, since many of them can’t or don’t want to return to Hungary? What are the values they should preserve and what should they give up now that Hungary is standing on its own feet? What can they give back to Hungary? What is their purpose for the future?

When we went home to Hungary in 1992, we met my half-siblings, who were already getting older at the time. It was the first and last time I saw them. I was so preoccupied with my life and career goals and family issues that I didn’t have the energy to maintain a relationship with them. Looking back, it was a mistake. My son connected with them last summer, so we haven’t lost each other completely. My father felt it was worth his efforts in preserving and building the Hungarian spirit in America. He lived to see Hungary liberated, to see the Hungarian scouting movement in exteris help restart the original scouting movement in Hungary. He was at peace with his convictions and their value.

What are your own memories related to the regime change of 1989–90 in Hungary?

I also found closure for the decades I spent being an American espousing my ethnic heritage and value in it. For example, back in 1977, together with Dr. Gábor Papp, I was one of the leaders of the movement pleading with the U.S. government to keep the Holy Crown of Hungary in America and not return it to the communist Hungarian government. We got national media attention, and the Congress had to pay attention to us about the importance of standing up for the truth the Holy Crown represented. Yet, change had already begun in the minds and hearts of the new generations born in America who grew up here, started families, and had to decide who they were, Americans or Hungarians, American Hungarians or Hungarian Americans. This was an important distinction, especially in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

In 1988 at a computer exhibition I met a team of Hungarian engineers who came to America from Műszertechnika, a company in Hungary, wanting to bring small computer peripheral devices to the Western markets. I saw potential in working together, we made an agreement. I went to discuss the collaboration with the FBI and CIA, who said I could work with Hungarians because communism would soon be over, in a few years anyway. In 1989 we set up a small but thriving joint company in Cleveland that dealt with computer technologies, especially in handling data storage drives, that these Hungarian engineers helped create. We sold tens of thousands of our products in America, and also in Europe. In late 1988 I took the Hungarian engineers who were working with me to various events in the local Hungarian community. When we sang the Szekler Anthem, they turned pale—it wasn’t allowed to do in communist Hungary or Romania at the time. The concept of Hungarians beyond the borders of Hungary also began to take shape and a larger goal started to be vocalized: Hungarians beyond the borders of Hungary are part of the nation. This also gave strength to the Hungarian Association to define its future.

How did you carry on? Tell us more about your Hungarian community activities.

I started as a computer engineer. It was very difficult for me to decide not to go into politics or history, which would have been my family legacy. Still, I helped my father in many ways. We co-wrote the book Faith & Faith, a short history of Hungary, in English. I decided to go in the direction of computers, but looking back, that was a mistake, because I could have lived my life better and more successfully if I had also focused on historical-political issues as a professor. However, my dream was that computers would change the world. And they did, but I thought it would happen much earlier, in the 1980s. The development of the computer world was initially very slow and only accelerated later, and there will be even bigger changes in the future. I’ve been waiting for AI all my life, it motivated me to choose this profession. Building the Hungarian community remained at the level of a ‘side business’ for me, but I saw a lot of value in it.

I’ve been attending and been involved in the Hungarian Association events since I was a child and have been a contributor and committee member since my university years. Today, I’m the oldest and the longest-serving member. I’ve been involved in editing and publishing the Krónika books since 1979. When we switched to computers, we published other books as well, such as summaries on the Hungarian school. Since 1995, together with Dr. János Nádas and his wife Gabriella, we’ve continued our work to keep the Somogyi–Nádas spirit alive. But what exists nowadays in the Hungarian Association doesn’t come close in any sense to what it once was. We exist, but not as we once did. In the past, many hundreds of participants came from all over the world to the Congress. They’ve passed away, and the younger generations have chosen new directions. The world and the way information is consumed have changed, largely thanks to computers and the internet. Our attention span has narrowed. Instead of books, we read short articles. As there was no longer sufficient demand, we finished the Krónika series with the 50th book in 2011. In the 2000s we gave a lot of recognition through the Árpád Order to those who deserved it for their previous work, but recently, we’ve only admitted one or two new members to the Árpád Academy. We hope we’ll be able to maintain the memory of those who have been recognized, so that more great personalities would be re-discovered, and their work would find its way back to Hungary. We’ve already tried to establish contact with the Hungarian Consulate to link the Árpád Academy with some Hungarian state recognition to give respect to those awarded in the past, proving that their work was meaningful.

What about your family?

My wife is Romanian, and she immigrated from Romania in 1992. We met several years later, in 1998, through a mutual friend. She never learned Hungarian, I never learned Romanian, so we speak English with each other but participate in each other’s cultural communities. We retained our languages because of our son. Ferenc speaks both languages, because I only spoke Hungarian to him and my wife only spoke Romanian. This wasn’t easy for us, but we persevered, because we saw value in it. I think it was thanks to this triple language culture that our son got into Princeton University. It gave him a value that he can leverage in the future in his intended profession of history and diplomacy. His goal is to research and promote cooperation between the peoples of Central Europe. That’s why he sees his future not so much in America, but in Europe. I’m very happy that he decided to carry on the family legacy. My wife is also an engineer, so until the last year of high school, our son thought he would also choose an engineering career. Once, however, while browsing in our basement, he saw his grandfather’s writings and started reading them. He also became very immersed in folk culture through the Regös (scout folk dance) Group as well as in Romanian folk culture. He realized his grandfather’s valuable work might be something he should continue.

Your son didn’t meet his grandfather, right?

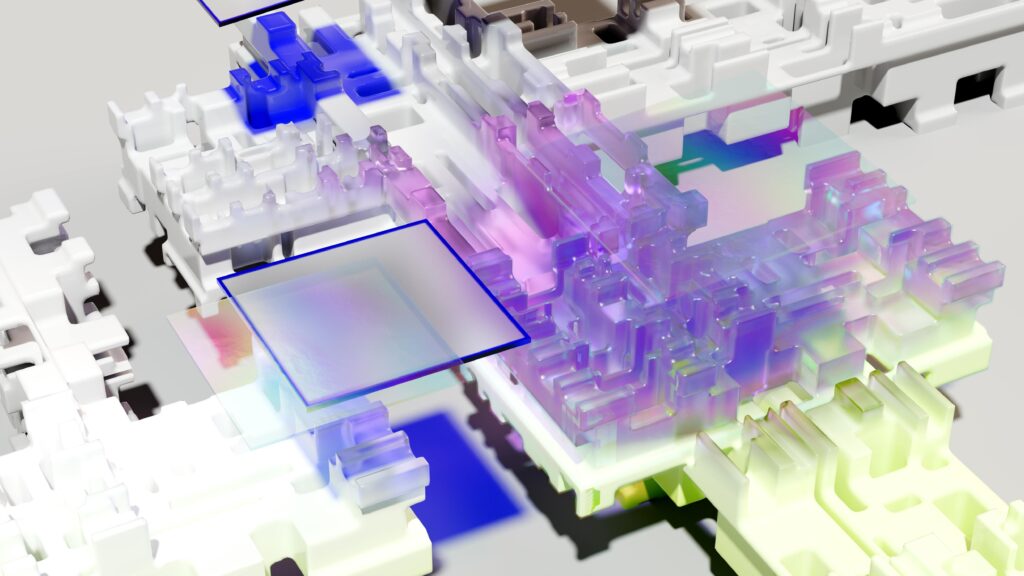

No, as my father died in 1995, while my son was born in 2002. I am two generations later than my father, and my son is also two generations later than me. So a generation was skipped between us. This is rare, but it has its advantages. Those with more usual generational timing didn’t get the special insights that I got directly from my father, and my son from me: an older, more traditional way of thinking. Those of the same age as me or my son no longer received all this, at least not so directly. It’s difficult, but not impossible, to provide young people with experiences that they value in relation to the preservation of national culture and identity. I see great potential in AI for sharing different generational views with technology. When a young person can learn from the computer, like from a grandparent, writer, or creator who is no longer alive, that’s a special gift new technology offers the AI-native generation. If I can feed my father’s work into the computer, I can ask questions using AI, such as asking my father. This is now a real possibility that can help preserve and save our cultures, strengthening ethnic groups living outside of national borders in their self-identity. It all depends on whether we use AI for good. I’ve been observing and waiting for this all my life, and there are signs that it will be used for good purposes, to carry on the good of humanity and human culture. If we can motivate young people to expand their cultural knowledge using computers with AI—they won’t do it by reading books anyway—, and if they are able to raise good questions and get accurate answers about the past, then there is hope that Hungarian national culture will continue to live outside the country’s borders.

Read more Diaspora interviews: