This is an abridged version of the original interview published in Reformátusok Lapja on 12 January 2025 and online on reformatus.hu on 31 January 2025.

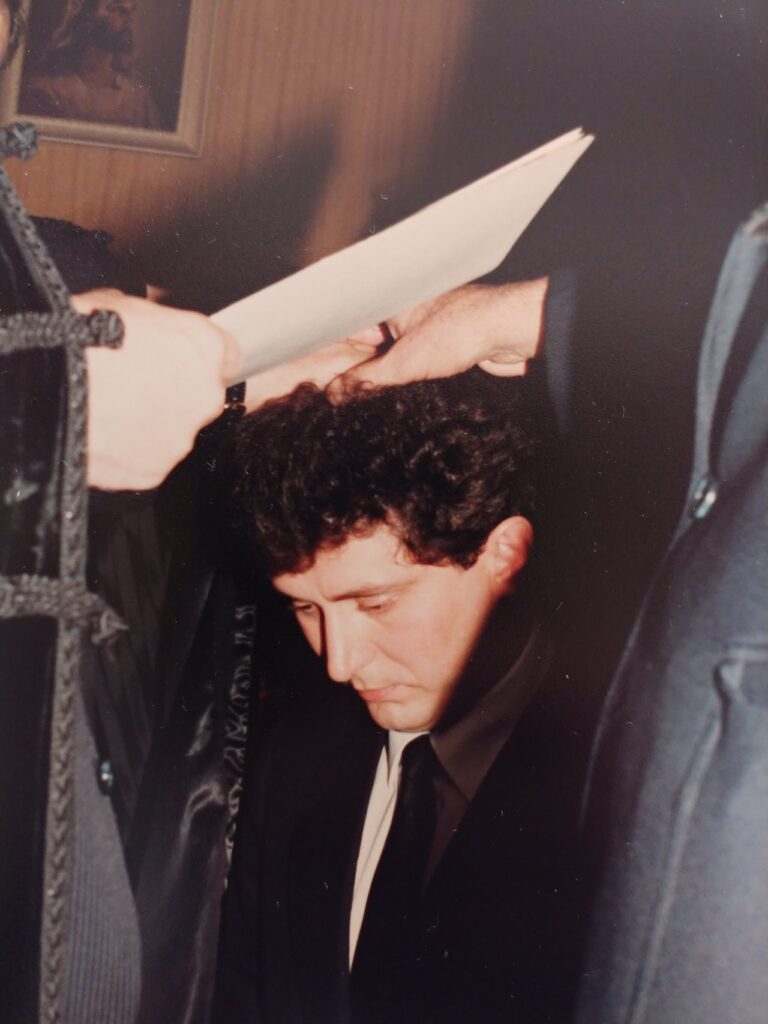

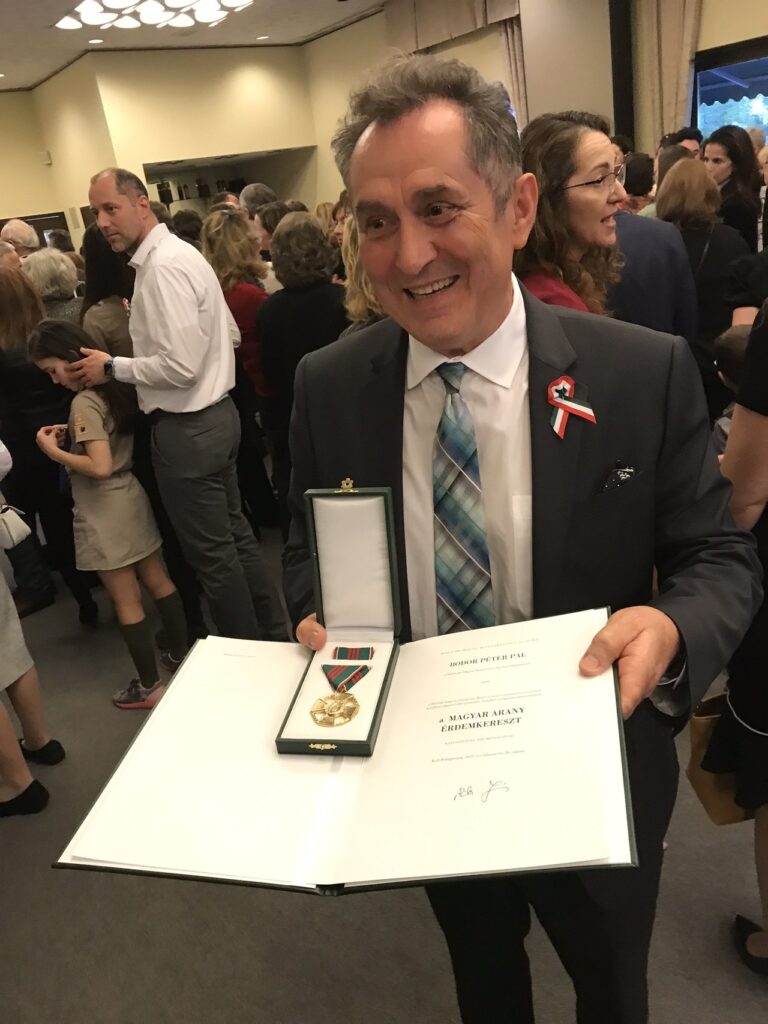

In 1983 the Transylvanian Bodor family arrived in America after an arduous journey, leaving behind a challenging pastoral life in Communist Romania. László Bodor served as a pastor for ten years during a turbulent period at the First Hungarian United Church of Christ of Miami while also serving at the Sarasota Mission Center. His wife, now 85-year-old Albinka, was a devoted partner in every aspect of his husband’s ministry. Their younger son, Péter Pál, while maintaining his secular career as an engineer, took over his father’s mission service in 1993 and temporarily led the Miami congregation. In 2019 he was awarded the Hungarian Gold Cross of Merit. He currently serves as the Vice Bishop of the Calvin Synod, which unites the Hungarian-speaking congregations of the United Church of Christ in America.

***

Could you recall your childhood in Romania?

Albinka: My father passed away in 1949 when I was ten years old—he couldn’t bear that the Communist regime had taken everything from him. My mother was sent to Bihar County to work as a teacher, so my two younger siblings and I stayed with our grandmother in Nagylak (Nădlac, Romania), a town near Arad, that had been split in two by the Treaty of Trianon in 1920. We were blacklisted as ‘kulaks’, which meant that two years later, I wasn’t allowed to enroll in the seventh grade of the church school run by the Slovak minority. I was admitted to the Romanian school, but it only had seven grades. I wanted to continue my studies at a high school, but I wasn’t accepted there either. My mother even took me to Nagyvárad (Oradea), hoping that they wouldn’t ask for our background papers there, but we were unsuccessful.

Péter Pál: Fortunately, high school graduation later became mandatory in Romania, and my mother was finally able to continue her education. After completing high school, she wanted to attend medical school, but she wasn’t even allowed to take the entrance exam…

What did you do instead?

Albinka: I played the organ, I sang, and I got married…(laugh) Aunt Mariska, our seamstress, mentioned that the local Reformed congregation was without an organist. I was 11 years old, and knew how to play the piano, so I went with her to play the organ. I was so small that my feet couldn’t reach the pedals. Later, I continued attending the Reformed congregation. When the Lutheran organist left to study in Kolozsvár (Cluj-Napoca), I filled in for him as well. I sometimes played at the Catholic church too. My grandmother was Catholic, so I knew the hymns. My mother loved music; all three of her children inherited excellent musical ears. I was the only one who played an instrument. When there was no pastor at our church, ministers from Arad came occasionally to serve in Nagylak. Among them was the late Bishop Kálmán Csiha, my husband’s seminary colleague and close friend. The first time I sang at the organ, it was alongside him. Previously, the pastors would sing while I played the keys.

How did you meet your husband?

Albinka: On 6 October 1956, after accompanying my Aunt Lujza to the train station in Arad, a young man boarded the bus back to Nagylak. The only available seat was next to me. I struck up a conversation with him, and it turned out that he was László Bodor, our new pastor…The Bodor family lived in Magyarlápos (Târgu Lăpuș), but at that time, they were forcibly evicted from their home. The Securitate—the Romanian Communist secret service—gave them 48 hours to leave. One year later, we got married. Zoltán Bodor, my father-in-law, was a royal Hungarian notary, and when Northern Transylvania was reassigned to Romania after World War II, he was imprisoned. He requested that his trial be held in Magyarlápos, where he was well known in the surrounding 40 Romanian villages. Many locals attended the trial, spoke in his defense, and pleaded for his release because he had helped them so much.

Péter Pál: Had the trial been held in Nagybánya (Baia Mare), where no one knew him, he might not have survived. Thus, the People’s Court acquitted him. By then, my uncle had been admitted to medical school and eventually became a doctor. After high school, my father was conscripted into a labor service for three years and worked as a laborer on the construction of the Danube–Black Sea Canal to pay for his brother’s tuition. When trying to enroll at the university, only the theological seminary accepted him. This was his salvation; he carried the gratitude of that opportunity in his heart for the rest of his life.

Where did you serve in Romania, and for how long?

Albinka: Our first child, Zolika (Zoltán), was born in Nagylak. When he was six months old, my husband was transferred to Ant, a wonderful, purely Hungarian village. That’s where Péter was born. Later, we lived in Nagybodófalva (Bodo) for eight years. It was also a completely Hungarian village, home to 1,800 people, with a beautiful church on the banks of the Bega River. That’s where our daughter, Albinka, was born. After that, we moved to Nagyzerind (Zerind).

Péter Pál: Meanwhile, an opening became available in the Gáj (Gai) district of Arad, a suburban congregation founded by Rev. Kálmán Csiha. My father applied for the position because the fast-growing suburban congregation attracted many intellectuals who didn’t dare attend the downtown church under Communist surveillance. For both the pastoral work and the education of the three children, Arad was a better place. At the time, there was only a prayer house and a parsonage—my parents started building the church.

Albinka: Wherever we moved, my husband restored and built something. When we arrived in Ant, he immediately visited the cemetery to understand the origins of the people there. Seeing it overgrown with weeds, he gathered the locals to clean it up and build a fence around it. He didn’t have to ask twice. My husband truly loved people, and they felt that. He knew how to inspire them, and you can still see his impact everywhere. In Arad, the parish was so small that we couldn’t fit inside with three children. Since the congregation had no money, my husband organized a communal effort, where everyone dug and built. Our 13-year-old son, Péter, was welding iron beams on the roof…We lived there for ten years.

Was the church completed?

Péter Pál: Unfortunately, no. In a village called Galgó (Gâlgău) near Magyarlápos, the Reformed community had once built a church designed by the famous Károly Kós, but over time, the Hungarian population disappeared, leaving the church abandoned. When my grandfather noticed this, he informed my father, who hoped that while new church construction was banned, reconstruction might be allowed. Brick by brick, pew by pew, bell by bell, we dismantled the old church and transported it to Arad. It was an amazing feeling to save everything—the pulpit, communion table, Moses seat, and bell! The Arad County authorities approved the plan, but Bucharest vetoed it. That was the final blow that broke my father’s spirit…

Albinka: When he sought help from Bishop László Papp to secure the missing permit, he was told: ‘If there won’t be a church, then at least you’ll have a nice, new prayer house.’ My husband was very disappointed.

Péter Pál: The church was never built. We stored everything and constructed a roof over the salvaged materials. The bricks had to be sold, but the wood, sacred objects, and bell remained. After the fall of Communism, the next pastor, Imre Cégé, revived the idea, and the church was eventually built. The original design by Károly Kós was too small, so they expanded it. The bells were reinstalled in the tower, once again calling worshippers after decades. The pulpit, Moses seat, and communion table were placed in the prayer house.

Albinka: Both projects were financially supported by Péter.

Why and how did you come to America?

Péter Pál: In 1982, my father was again sent to the Netherlands to seek aid. He decided to travel by car and take my mother and me along. After completing my third year at the seminary, I requested permission to accompany them.

Albinka: When we set out in the morning, my son Zoli leaned into the car window and said: ‘Dad, if you love us, you won’t come back…’ Along the way, we thought it through: God had opened a door for us, a way to escape the horrors we were living in. Perhaps if I had known what awaited us here, we wouldn’t have dared to leave. It’s better that I didn’t know.

Péter Pál: We reached Austria via Újvidék (Novi Sad, then Yugoslavia) and applied for asylum. István Szépfalusi, a Lutheran pastor living there, warned us that we had to apply in the first independent country we arrived in—if we left, we would lose the chance. At the time, it was said that Germany wasn’t accepting Protestant pastors because otherwise, all the Transylvanian Saxon Lutheran churches would have emptied out. Austria, being a Catholic country, had Szépfalusi serving the Protestant community, so my father wouldn’t have been able to get a position there. Thus, America became the goal. Szépfalusi called Bishop Dezső Ábrahám of Detroit, who promised to sponsor us.

Albinka: We arrived in New York in March 1983. From there, we traveled through Detroit, Michigan, to Cleveland, Ohio, where my husband’s cousin, Aliz Bodor, lived. A month later, a pastoral position opened up in the Windsor congregation in Canada.

Péter Pál: Meanwhile, my parents realized they couldn’t stay in Canada, or we would lose our U.S. political status and the right to bring my siblings over. Around that time, the Miami congregation had a pastoral vacancy. My father applied, and in February 1984, he was elected.

What happened in Florida? How did he manage with the language?

Péter Pál: Most of the congregational life is still in Hungarian today, including the minutes and the worship services. Occasionally, a short English greeting is needed. However, they arrived in a turbulent congregation with Hungarians from various places like Chicago, Cleveland, and New York. The community wasn’t homogeneous, and tensions arose frequently. My father had a difficult time; he suffered two heart attacks during the ten years he served there.

Albinka: The first Hungarian Protestant pastor in Miami was Péter Antal, a retired minister who arrived in the late 40s. Initially, services were held in his home, but later, the First Hungarian United Church of Christ was officially founded. They purchased land in the church’s name and first built the Kossuth Hall in the early 50s, followed by the church itself—all through their own efforts. In the early 70s, under Pastor István Szőke, they built apartment houses. If he hadn’t been there, the Hungarian church in Miami wouldn’t have the financial foundation to sustain itself today. In the early 90s, during my husband’s tenure, the Petőfi Youth Hall was constructed.

How large was the congregation?

Péter Pál: During my father’s time, 50–70 people attended worship services regularly, and on major holidays, there were 150 attendees. At Easter, Christmas, the Anna Ball, the Harvest Festival, or the New Year’s Ball, up to 300 guests would fill the hall. After every Sunday service, there was a community lunch. There was also an active and sizable women’s group, made up of women aged 45 to 70, who organized events and cooked meals. My mother was the church organist and cantor. Many Hungarian artists and literary figures visited, including Gyula Bodrogi, József Simándy, István Csurka, and Lajos Für. This all lasted until 1 July 1994, when my father underwent serious heart surgery and was forced into medical retirement. He didn’t want to leave the congregation, but my brother and I convinced him that his life was more important. ‘Everything has its allocated time,’ we told him. His pastoral service should not have continued if he was exhausted, stressed, and unwell. The congregation’s general assembly approved his retirement, and my father withdrew peacefully.

Did you take over your father’s role after his retirement?

Péter Pál: No. My secular job and the Sarasota mission already filled my life, so I couldn’t take on leading the Miami congregation as well. However, I always stepped in when emergencies arose—and there were quite a few…For example, in the winter of 2014, I accepted the position of acting pastor, without salary. What was supposed to be a one-year commitment turned into two and a half years until we found a new pastor. Later, I stepped in again until Rev. Lóránd Csiki-Mákszem and his family arrived. Many asked me why I didn’t take the position permanently. I had my reasons, but I always trusted that God would provide a solution. We just needed to bridge the gap until things settled. Now that we have a full-time pastor, the congregation is finally thriving.

Why did you take on the Sarasota mission? How big is the community?

Péter Pál: Sarasota has a Hungarian mission community, a registered small congregation founded during my father’s time. When my father retired in 1993, I voluntarily took over this community alongside my secular job, and I have served it ever since, without salary. We don’t have our own church; we rent at a very reasonable rate. I hold services once a month—except during the summer—and on major holidays. I also perform funerals, baptisms, and weddings, fulfilling all pastoral duties. Often, I spend long weekends with them, visiting families. Sometimes, I’m invited to Naples and Fort Myers as well. My mother played the organ there for many years with my father, and later with me, but she can’t manage it anymore. We currently live in Fort Lauderdale, and I commute from there. For over 30 years, every time I serve, I leave at 9am and return home after midnight. Attendance varies; there are 30–40 people at a typical service and up to 60 on major holidays.

You aren’t only a theologian, but also an engineer and businessman. Why?

Péter Pál: While preparing for confirmation, I felt a strong spiritual calling. At the time, it wasn’t a direct calling to be a pastor, but it was an awakening. With a few young friends and colleagues, I regularly read the Bible. When it came time to choose a profession, I had to decide between becoming a mechanical engineer or a theologian. I chose the latter. During the Communist Ceaușescu era, even theoretical high school students were forced into vocational training. One day a week, I had to work at a factory near Arad. So, I ended up attending a technical high school. After that, I completed three years of seminary; then we left for America. I never considered abandoning theology. I became a student at Ashland Theological Seminary in Ohio, where Bishop Csaba Krasznai also earned his doctorate. After obtaining my Master of Divinity degree, I was ordained in 1986. Then, the Flint congregation in Michigan elected me as their pastor. I loved that community, but I missed learning. So, I enrolled at The University of Michigan in Flint. Alongside my pastoral duties, I completed my studies in four and a half years and earned a Bachelor of Science degree.

Your brother invited you to Florida. When did they arrive in the U.S.?

Albinka: When we became U.S. citizens, we were finally able to apply for family reunification visas. In 1989, my other two children were finally able to leave Romania with their families. By then, my daughter was also married. Her husband worked in construction in Florida, and she completed cosmetology school, working in that field for ten years before joining Zoltán’s company. He first worked for a cable television company, then moved into medical equipment before finally starting his own business. When they arrived in America, my first grandchild was six years old; today, he is married, and I have two great-grandchildren. My daughter has two sons; one is married and has one son.

Péter Pál: In 1993 my brother asked me to move to Florida to help him with the company we co-founded. Most of our family still works there today. Since I always prioritized succession planning, I didn’t want to leave my congregation in Flint without a pastor. I convinced Zoltán Sütő, a deeply faithful Reformed police officer, to take over the Sunday school and youth group. When he retired, I encouraged him to enroll in seminary. He completed his studies and eventually became my successor. Since then, the Bodor family has lived together in the Fort Lauderdale area, supporting each other through good times and bad.

As a pastor’s wife, what were your responsibilities? What happened to you and your husband after his retirement?

Albinka: I did everything that was needed at any given time. If necessary, I cooked, played the organ, led the choir, ran Sunday school, handled office work, and managed the apartments. At least once a week, we went on family visits.

Péter Pál: In Miami, there was a Church World Service office, and they asked my mother to help translate from Slovak, Romanian, and Hungarian into English. She has an exceptional talent for languages and learned English quickly and well. She often had to act as an interpreter, which meant she frequently appeared before immigration officials. Because of this, she was well-known among immigration officers, and she could get a meeting with them anytime. As a result, she helped countless people obtain legal status in the U.S. My father was always a highly active and exceptionally strategic thinker, but he didn’t focus on details. Whenever someone asked him about something specific, his answer was always: ‘Ask my wife!’ In 2009, at the age of 80, my father passed away. After his heart surgery, God granted him 15 more years. In the 90s, my parents bought land in Central Florida, and we built homes together. They lived there for a few years, but they also spent several summers in Nagylak. My father loved returning there—after all, that’s where they met, and in many ways, that’s where their shared journey came full circle…

Read more Diaspora interviews: